The Relevance and Transcendence of Ornament: a New Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Home Elevators

Home Elevators Live in your home with comfort and style Why a residential elevator Make your life more comfortable with a Garaventa Lift Solution • Comfortably overcome any barriers and tiring stairs. Reduce heavy lifting when transporting storage, • laundry or groceries. • An investment for your future accessibilty needs. • Choose from a variety of materials and finishes to fit your style and taste. • Our elevators are easy to install, especially in existing buildings. • Make daily routines easier! • A Garaventa Home Elevator will quickly become part of everyday life. 2 Why Garaventa Lift Garaventa Lift has been moving people since 1928. Our products have always stood the test of time. We began by building ropeways in the Swiss Alps. Garaventa Lift has since become a global organization, representing reliability, safety, and innovation. For over 90 years we have been designing the best mobility solutions for people to make every move comfortable and safe. Our secret? Customer proximity all the way, from the choice of the home elevator to after installation. Consultation Design Installation Servicing 3 Bring efficiency to your home Add value to your home A Garaventa Lift Home Elevator significantly increases the value of your house while other accessibility solu- tions can decrease the resale value. Compared to the costs of moving, a home elevator is a small investment that gives you and your family the peace of mind for now and for your future. Few steps in simplicity Comfortably overcome the few entrance steps and, why not, bring in the shopping bags too. Your guests will be impressed by the style and will appreciate the comfort and ease that a Garaventa Lift Home Eleva- tor brings to your home. -

TW-15 Typical Balcony/Breezeway Detail

P.O. Box 1404 Joplin, MO 64802-1404 Typical Balcony/Breezeway Detail 800-641-4691 1 inch TW-15 All logos are cmyk tamkowaterproofing.com If needed, TAMKO red is PMS185 1.5 inch FINISHED WALL When to use:Or metal counterflashing at openings. page up to 6 inches = 1 inch TWM-1 MASTIC WEATHER RESISTANT BARRIER or other appropriate, page up to 12 inches = 1.5 inch Positioned to lap TW-60 12" flashing in shingle fashion. compatible sealant at page up to 18 inches = 2 inch membrane and metal page over 18 inches = 2.5 inch flashing terminations. TW-60 12" FLASHING 2 inch Positioned with 4" minimum on horizontal leg and PRIMED 26 GA. 2" minimum beyond vertical leg of metal flashing. The use of TW-60 18" Flashing is (MINIMUM) GALVANIZED recommended in regions that experience heavy snow fall and ice buildup. METAL L-FLASHING (4" × 4" MINIMUM) TW-60 SHEET WATERPROOFING MEMBRANE Prime metal flashing prior to TAMKO red is PMSPlywood 185, or OSB deck must be fully covered. installation with TWP-1 or CONCRETE which according to the TWP-2 primer. 2.5 inch logo standards breaks TWM-1 MASTIC down to be M100, Y80 or other appropriate, compatible sealant at TW-60 termination as a cant. ADHESIVE PRIMER* METAL FLASHING EXTRUDED ALUMINUM BALCONY EDGING (T-BAR) FASTENERS Cross-sectional shape varies. Fasten per Positioned 1" from the PLYWOOD or OSB DECK manufacturer’s recommendations. outside edges of the 1/4":12" minimum positive slope 1 inch flashing. Fastener type required away from wall to drain and and spacing as prevent ponding water. -

New York City Fire Code Guide

NYC FIRE CODE GUIDE CODE DEVELOPMENT UNIT BUREAU OF FIRE PREVENTION April 28, 2021 Table of Contents GENERAL QUESTIONS ....................................................................................................................... 2 FC CHAPTER 1 - ADMINISTRATION ..................................................................................................... 5 FC CHAPTER 2 - DEFINITIONS .......................................................................................................... 10 FC CHAPTER 3 - GENERAL PRECAUTIONS AGAINST FIRE .................................................................... 11 FC CHAPTER 4 - EMERGENCY PLANNING AND PREPAREDNESS ............................................................ 19 FC CHAPTER 5 - FIRE OPERATION FEATURES..................................................................................... 22 FC CHAPTER 6 - BUILDING SERVICES AND SYSTEMS ......................................................................... 47 FC CHAPTER 8 –INTERIOR FURNISHINGS, DECORATIONS AND SCENERY ............................................. 55 FC CHAPTER 9 - FIRE PROTECTION SYSTEMS .................................................................................... 59 FC CHAPTER 10 - MEANS OF EGRESS ............................................................................................... 68 FC CHAPTER 12 - DRY CLEANING ..................................................................................................... 71 FC CHAPTER 14 - FIRE SAFETY DURING CONSTRUCTION, ALTERATION AND -

Safety Barrier Guidelines for Residential Pools Preventing Child Drownings

Safety Barrier Guidelines for Residential Pools Preventing Child Drownings U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission This document is in the public domain. Therefore it may be reproduced, in part or in whole, without permission by an individual or organization. However, if it is reproduced, the Commission would appreciate attribution and knowing how it is used. For further information, write: U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission Office of Communications 4330 East West Highway Bethesda, Md. 20814 www.cpsc.gov CPSC is charged with protecting the public from unreasonable risks of injury or death associated with the use of the thousands of consumer products under the agency’s jurisdiction. Many communities have enacted safety regulations for barriers at resi- dential swimming pools—in ground and above ground. In addition to following these laws, parents who own pools can take their own precau- tions to reduce the chances of their youngsters accessing the family or neighbors’ pools or spas without supervision. This booklet provides tips for creating and maintaining effective barriers to pools and spas. Each year, thousands of American families suffer swimming pool trage- dies—drownings and near-drownings of young children. The majority of deaths and injuries in pools and spas involve young children ages 1 to 3 and occur in residential settings. These tragedies are preventable. This U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) booklet offers guidelines for pool barriers that can help prevent most submersion incidents involving young children. This handbook is designed for use by owners, purchasers, and builders of residential pools, spas, and hot tubs. The swimming pool barrier guidelines are not a CPSC standard, nor are they mandatory requirements. -

Working from Home How to Stay More Organized

Working from Home How to Stay More Organized Yvonne Glasgow ©2020 by LifeSavvy Media. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Create a Workspace ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Make Sure Everything Has a Home ............................................................................................................... 2 Keep Your Workspace Tidy ........................................................................................................................... 2 Organize Your Computer Desktop, Too ........................................................................................................ 3 Introduction Working from home fulltime, with multiple projects going on, can leave your home office and the rest of your house looking a mess. Here's how to stay organized when your house is also your office. A disorganized home and office can distract you from getting work done. Luckily, there are some steps you can take to get and stay organized. By keeping your home and office decluttered and neat, you give yourself space where you can get stuff done. More importantly, a -

Glossary of Terms

143 Glossary of Terms Baluster: A vertical support used to fill the open area between the rail and the stair or landing. Balustrade: A complete rail system that includes the handrail, balusters, and newel posts. Box newel: An oversize square newel that is usually hollow and is used in a post-to-post balustrade system. Brackets: Ornamental pieces fastened beneath the tread on the open side of a stair; also know as tread brackets. Building code: A set of legal requirements established by various governing agencies that covers the minimum regulations for all types of construction, including stair construction. Bullnose starting step or tread: A starting tread that has one or both ends rounded to a semi-cir- cle and projecting beyond the face of the stair stringer. Cap: The part of the fitting that accepts the newel post; used in conjunction with a pin top newel in an over the post balustrade system. Carriage: See stringer. Easement: The over or under ramp of a stair or rail. False Tread Caps: A piece attached to the end of a rough tread to simulate solid wood treads, usu- ally with a carpet runner down the steps. Fillet: A thin strip that is usually flat on one side and fits into the plow of a piece of handrail or shoe rail. Flight: A continuous series of steps with no intermediate landings. Gooseneck: A fitting that is used in the transition of a handrail to a landing or balcony; compen- sates for the change in the rise of the stair and may make a change in direction. -

Installing Alley-Gates

INSTALLING ALLEY-GATES: PRACTICAL LESSONS FROM BURGLARY PREVENTION PROJECTS Briefing Note 2/01 Shane Johnson and Camille Loxley July 2001 “The views expressed in this briefing note are those of the authors, not necessarily those of the Home Office (nor do they reflect Government policy).” Introduction Benefits of an alley-gate Alley-gating, the installation of security gates across Reducing burglary footpath and alleyways, is a form of situational crime Results from the 1998 British Crime Survey1 showed prevention that attempts to reduce the opportunity to that 55% of burglaries with entry occurred through the commit crimes such as domestic burglary. When rear in terraced and detached/semi-detached houses. installed and properly used, alley-gates should control Moreover, an analysis of recorded crime data for the access to vulnerable target areas – usually paths or county of Merseyside shows that this pattern is alleys at the rear and to the sides of houses. Although particularly evident for terraced housing, with entry there are good reasons for thinking that alley-gates being gained via the rear of the property for around 72% should reduce burglary, there is as yet little hard of burglaries. The implication of such findings is that in evidence that they do. This will be available later in the theory, by restricting access to the rear of properties, year when evaluations of projects funded by the Crime alley-gating should have a very significant effect on Reduction Programme report their findings. In the burglary, although there are as yet no impact interim, however, the promise of alley-gating is enough evaluations of alley-gating schemes available. -

Technical Memo.Pdf

COMMITMENT & INTEGRITY 35 New England Business Ctr. T 866.702.6371 DRIVE RESULTS Suite 180 T 978.557.8150 Andover, Massachusetts 01810 F 978.557.7948 www.woodardcurran.com TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM TO: Donald Robinson FROM: Jeffrey Hamel DATE: May 15, 2009 SUBJECT: Summary Data Report – Window Glazing and Existing Indoor Sample Data Lederle Graduate Research Center, Amherst, Massachusetts INTRODUCTION In March 2009 a limited hazardous building materials investigative survey and assessment was conducted by Environmental Health & Engineering, Inc. (EH&E) for Fitzemeyer & Tocci, Inc., to identify asbestos- containing materials, lead in paint, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and other hazardous building materials in anticipation of renovations planned at the Lederle Graduate Research Center (LGRC) low rise building. A report documenting the survey was submitted to the University on March 25, 2009. During the assessment, a sample of the interior window glazing from the third floor conference room of the Science Library was collected and analyzed for PCBs. This sample and a duplicate of this sample detected total PCBs at concentrations of 12,000 parts per million (ppm) and 11,000 ppm, respectively. Given that these concentrations exceed regulatory thresholds per Federal regulations (40 CFR 761) for PCBs in a non-totally enclosed manner, the University retained the services of Woodard& Curran to work with the University to develop an approach and plan to address these conditions. This memorandum presents the results from an initial assessment of the window glazing performed in April/May 2009 and summarizes existing indoor sample data collected within the LGRC building. INITIAL ASSESSMENT This initial assessment included an inspection and inventory of the windows in the low rise and Tower A of the LGRC followed by the collection of representative samples for PCB analyses. -

HOME OFFICE SOLUTIONS Hettich Ideas Book Table of Contents

HOME OFFICE SOLUTIONS Hettich Ideas Book Table of Contents Eight Elements of Home Office Design 11 Home Office Furniture Ideas 15 - 57 Drawer Systems & Hinges 58 - 59 Folding & Sliding Door Systems 60 - 61 Further Products 62 - 63 www.hettich.com 3 How will we work in the future? This is an exciting question what we are working on intensively. The fact is that not only megatrends, but also extraordinary events such as a pandemic are changing the world and influencing us in all areas of life. In the long term, the way we live, act and furnish ourselves will change. The megatrend Work Evolution is being felt much more intensively and quickly. www.hettich.com 5 Work Evolution Goodbye performance society. Artificial intelligence based on innovative machines will relieve us of a lot of work in the future and even do better than we do. But what do we do then? That’s a good question, because it puts us right in the middle of a fundamental change in the world of work. The creative economy is on the advance and with it the potential development of each individual. Instead of a meritocracy, the focus is shifting to an orientation towards the strengths and abilities of the individual. New fields of work require a new, flexible working environment and the work-life balance is becoming more important. www.hettich.com 7 Visualizing a Scenario Imagine, your office chair is your couch and your commute is the length of your hallway. Your snack drawer is your entire pantry. Do you think it’s a dream? No! Since work-from-home is very a reality these days due to the pandemic crisis 2020. -

Indoor Air Quality Guidelines for Multifamily Building Upgrades

Publication No. EPA 402/K-16-/01 January 2016 Preface How to protect public health, save energy and reduce climate change impacts — all at the same time These Energy Savings Plus Health: Indoor Air Quality Guidelines for Multifamily Building Upgrades are part of EPA’s approach to addressing three of our most pressing environmental and public health priorities: reducing asthma and other health disparities, our reliance on fossil fuels, and climate change impacts. These guidelines will be a valuable tool in helping to ensure the health, comfort and safety of the many Americans living in multifamily buildings. More than 80 million Americans, about 25 percent of the U.S. population, live in multi-unit homes. About one-quarter of these residents live below the poverty line and a large percentage of residents of affordable housing are children, the elderly or disabled. These groups are the most vulnerable, and they are disproportionately impacted by diseases like asthma and commonly exposed to serious health risks from secondhand tobacco smoke, usually at home. Heating and cooling buildings uses a lot of energy — about 43 percent of all energy use in the United States! Producing this energy requires us to burn fossil fuels like coal and oil, which contributes to air pollution and generates large amounts of greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change. Improving the energy efficiency of buildings usually involves tightening the buildings through air sealing and other weatherization techniques to reduce the escape of air that we have just spent money to heat or cool. That’s a very good thing. -

Guidelines for Member-Led Tours Into the Capitol Dome General

GUIDELINES FOR MEMBER-LED TOURS INTO THE CAPITOL DOME GENERAL Member Must Accompany Group – Members are responsible for their guests and must accompany them during the entire tour. Availability – Dome tours are available to Members of Congress only and are conducted by US Capitol Visitor Center Guides Hours of Operation – Tours are available Monday through Friday from 9:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. Tours last between 45-60 minutes. One (1) tour per hour is available. Group Size – To ensure that a safe evacuation is possible, group size is limited to the Guide, the Member, plus a maximum of seven (7) guests. Scheduling – To request a tour, please call Visitor Services at (202) 593-1762. Requests may be made up to sixty (60) days in advance and are processed in the order in which they are received on a space available basis. Severe Weather – Weather-permitting, the Guide will take Dome Tour groups to the balcony beneath the Statue of Freedom. However, during periods of severe weather (i.e., thunderstorms, lightning, snow, and high wind), the Guide will conduct a Dome Tour of the internal space only. Where to Meet for the Tour – The Member should bring the tour group to the Crypt of the Capitol and meet the Guide at the Office of Congressional Accessibility Services, which is located in the Crypt (room S-156). Waiver Forms – Signed waiver forms must be given to the Guide prior to the beginning of the tour. Children – Children may participate in Dome Tours, but, due to the nature of the tour route, the tour is not recommended for children under the age of 10. -

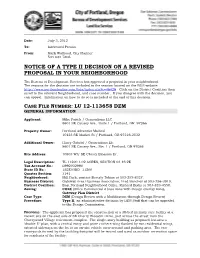

Notice of a Type II Decision on a Proposal in Your Neighborhood

Date: July 3, 2012 To: Interested Person From: Mark Walhood, City Planner 503-823-7806 NOTICE OF A TYPE II DECISION ON A REVISED PROPOSAL IN YOUR NEIGHBORHOOD The Bureau of Development Services has approved a proposal in your neighborhood. The reasons for the decision are included in the version located on the BDS website http://www.portlandonline.com/bds/index.cfm?c=46429. Click on the District Coalition then scroll to the relevant Neighborhood, and case number. If you disagree with the decision, you can appeal. Information on how to do so is included at the end of this decision. CASE FILE NUMBER: LU 12-113658 DZM GENERAL INFORMATION Applicant: Mike Parich / Generations LLC 8601 SE Causey Ave., Suite 1 / Portland, OR 97266 Property Owner: Portland Adventist Medical 10123 SE Market St / Portland, OR 97216-2532 Additional Owner: Harry Gabriel / Generations Llc 8601 SE Causey Ave., Ste. 1 / Portland, OR 97086 Site Address: 10803 WI/ SE Cherry Blossom Dr. Legal Description: TL 11200 1.02 ACRES, SECTION 03 1S 2E Tax Account No.: R992032990 State ID No.: 1S2E03BD 11200 Quarter Section: 3141 Neighborhood: Mill Park, contact Beverly Tobias at 503-255-8327. Business District: Gateway Area Business Association, Fred Sanchez at 503-256-3910. District Coalition: East Portland Neighborhood Office, Richard Bixby at 503-823-4550. Zoning: CO2d (Office Commercial 2 base zone with Design overlay zone), Gateway Plan District Case Type: DZM (Design Review with a Modification through Design Review) Procedure: Type II, an administrative decision by BDS Staff that can be appealed to the Design Commission. PROPOSAL: The applicant has proposed the construction of a 38-bed memory care facility at a vacant site on the east side of SE Cherry Blossom Drive, just across the street from the Cherrywood Village retirement complex.