The Plain-Fronted Thornbird: Nest Construction, Material Choice, and Nest Defense Behavior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

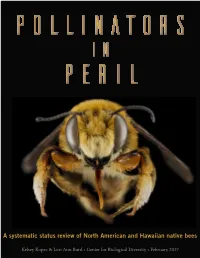

Pollinators in Peril: a Systematic Status Review of North American

POLLINATORS in Peril A systematic status review of North American and Hawaiian native bees Kelsey Kopec & Lori Ann Burd • Center for Biological Diversity • February 2017 Executive Summary hile the decline of European honeybees in the United States and beyond has been well publicized in recent years, the more than 4,000 species of native bees in North W America and Hawaii have been much less documented. Although these native bees are not as well known as honeybees, they play a vital role in functioning ecosystems and also provide more than $3 billion dollars in fruit-pollination services each year just in the United States. For this first-of-its-kind analysis, the Center for Biological Diversity conducted a systematic review of the status of all 4,337 North American and Hawaiian native bees. Our key findings: • Among native bee species with sufficient data to assess (1,437), more than half (749) are declining. • Nearly 1 in 4 (347 native bee species) is imperiled and at increasing risk of extinction. • For many of the bee species lacking sufficient population data, it’s likely they are also declining or at risk of extinction. Additional research is urgently needed to protect them. • A primary driver of these declines is agricultural intensification, which includes habitat destruction and pesticide use. Other major threats are climate change and urbanization. These troubling findings come as a growing body of research has revealed that more than 40 percent of insect pollinators globally are highly threatened, including many of the native bees critical to unprompted crop and wildflower pollination across the United States. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Relatedness Constrains Virulence in an Obligate Avian Brood Parasite

Ornithol Sci 15: 191 – 201 (2016) ORIGINAL ARTICLE Relatedness constrains virulence in an obligate avian brood parasite James W. RIVERS1,#,* and Brian D. PEER2 1 Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology, University of California, Santa Barbara, California 93106, USA 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Western Illinois University, Macomb, Illinois 61455, USA ORNITHOLOGICAL Abstract Virulence, the amount of harm a parasite inflicts on its host, is integral to elucidating the evolution of obligate avian brood parasitism. However, we lack infor- SCIENCE mation regarding how relatedness is linked to changes in behavior and the degree of © The Ornithological Society harm that brood parasites cause to their hosts (i.e., virulence). The kin competition of Japan 2016 hypothesis combines theory from offspring signaling and parasite virulence models and states that the begging intensity of co-infecting parasites is driven by their relat- edness, with concomitant changes in the degree of virulence expressed by parasitic young. We tested this hypothesis using the Brown-headed Cowbird Molothrus ater, an obligate brood parasitic bird whose virulence at the nestling stage is mediated by vigorous begging displays that are used to outcompete host young during feed- ing bouts. We found support for both predictions of the kin competition hypothesis: first, the begging intensity of cowbirds was greater in a population where cowbirds typically competed against unrelated host nestmates, relative to a population where they often competed against kin. Second, the greater intensity of begging in cowbirds was positively associated with decreased growth in host offspring during the devel- opmental period. Given the dearth of studies on virulence in avian brood parasites, our results notably extend our understanding of how relatedness is linked to parasite behavior and virulence, and they highlight how spatially-isolated host populations can harbor different levels of virulence that are driven by competitive interactions between co-infecting parasites. -

TOP BIRDING LODGES of PANAMA with the Illinois Ornithological Society

TOP BIRDING LODGES OF PANAMA WITH IOS: JUNE 26 – JULY 5, 2018 TOP BIRDING LODGES OF PANAMA with the Illinois Ornithological Society June 26-July 5, 2018 Guides: Adam Sell and Josh Engel with local guides Check out the trip photo gallery at www.redhillbirding.com/panama2018gallery2 Panama may not be as well-known as Costa Rica as a birding and wildlife destination, but it is every bit as good. With an incredible diversity of birds in a small area, wonderful lodges, and great infrastructure, we tallied more than 300 species while staying at two of the best birding lodges anywhere in Central America. While staying at Canopy Tower, we birded Pipeline Road and other lowland sites in Soberanía National Park and spent a day in the higher elevations of Cerro Azul. We then shifted to Canopy Lodge in the beautiful, cool El Valle de Anton, birding the extensive forests around El Valle and taking a day trip to coastal wetlands and the nearby drier, more open forests in that area. This was the rainy season in Panama, but rain hardly interfered with our birding at all and we generally had nice weather throughout the trip. The birding, of course, was excellent! The lodges themselves offered great birding, with a fruiting Cecropia tree next to the Canopy Tower which treated us to eye-level views of tanagers, toucans, woodpeckers, flycatchers, parrots, and honeycreepers. Canopy Lodge’s feeders had a constant stream of birds, including Gray-cowled Wood-Rail and Dusky-faced Tanager. Other bird highlights included Ocellated and Dull-mantled Antbirds, Pheasant Cuckoo, Common Potoo sitting on an egg(!), King Vulture, Black Hawk-Eagle being harassed by Swallow-tailed Kites, five species of motmots, five species of trogons, five species of manakins, and 21 species of hummingbirds. -

P0802-P0805.Pdf

802 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS The Condor962702-805 0 The CooperOrnithological Society 1994 ACTIVITY, SURVIVAL, INDEPENDENCE AND MIGRATION OF FLEDGLING GREAT SPOTTED CUCKOOS ’ MANUEL SOLER, Jo& JAVIER PALOMINO AND JUAN GABRIEL MARTINEZ Departamento de Biologia Animal y Ecologia, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidadde Granada, E-18071 Granada, Spain JUANJosh SOLER Department of Zoology, Uppsala University, Villaviigen9, S-772 36 Uppsala, Sweden Key words: Broodparasitism;Clamator glandarius; description of the study site is given in Soler (1990) Great SpottedCuckoo; magpie; parental care:Pica pica; and Soler et al. (in press). post-fledgingdependence. In all nests found, chicks were banded with num- bered aluminium rings (Spanish Institute for Nature Parental care of fledglingstends to last at least as long Conservation-ICONA). In 1991, a total of 19 Great as that of nestlings, and in some casestwice as long Spotted Cuckoo chicksreared in 13 parasitizedmagpie (Skutch 1976). The post-fledging dependence period nests were fitted with radiotransmitters. In 1992, 21 (hereafter called fledalina DeiiOd)is critical for iuvenile cuckoochicks and four magpiechicks were radio-tagged. survival (Royama 1$66rSullivan 1989) and the prob- In 1992, only one cuckoo chick in each nest was pro- ability of survival to independence appears to be an vided with a radiotransmitter and all were weighed adequate estimate of relative probabilities of survival with a 300 g Pesola spring balance one or two days to breeding in many bird species(Magrath 1991). before they left the nest. Other cuckoo chicks in these For avian brood parasites,very little is known about nestswere given a unique combination of color bands the behavior of foster parents in relation to their fledg- to enable individual recognition. -

Citizen Scientist Pollinator Monitoring Guide

Pennsylvania Native Bee Survey Citizen Scientist Pollinator Monitoring Guide Revised for Pennsylvania By: Leo Donovall and Dennis vanEngelsdorp Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture The Pennsylvania State University Based on the “California Pollinator Project: Citizen Scientist Pollinator Monitoring Guide” Developed By: Katharina Ullmann, Tiffany Shih, Mace Vaughan, and Claire Kremen The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation University of California at Berkeley The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation is an international, nonprofit, member-supported organization dedicated to preserving wildlife and its habitat through the conservation of invertebrates. The Society promotes protection of invertebrates and their habitat through science-based advocacy, conservation, and education projects. Its work focuses on three principal areas – endangered species, watershed health, and pollinator conservation. For more information about the Society or on becoming a member, please visit our website (www.xerces.org) or call us at (503) 232-6639. Through its pollinator conservation program, the Society offers practical advice and technical support on habitat management for native pollinator insects. University of California Berkeley collaborates with the Xerces Society on monitoring pollinator communities and pollination function at farm sites before and after restoration. University of California Berkeley conducts studies to calibrate the observational data collected by citizen scientists against the specimen-based data collected by scientists -

The Avifauna of El Angolo Hunting Reserve, North-West Peru: Natural History Notes

Javier Barrio et al. 6 Bull. B.O.C. 2015 135(1) The avifauna of El Angolo Hunting Reserve, north-west Peru: natural history notes by Javier Barrio, Diego García-Olaechea & Alexander More Received 10 December 2012; final revision accepted 17 January 2015 Summary.—The Tumbesian Endemic Bird Area (EBA) extends from north-west Ecuador to western Peru and supports many restricted-range bird species. The most important protected area in the region is the Northwest Biosphere Reserve in Peru, which includes El Angolo Hunting Reserve (AHR). We visited AHR many times between 1990 and 2012. Among bird species recorded were 41 endemic to the Tumbesian EBA and six endemic subspecies that may merit species status, while 11 are threatened and eight are Near Threatened. We present ecological or distributional data for 29 species. The Tumbesian region Endemic Bird Area (EBA) extends from Esmeraldas province, in north-west Ecuador, south to northern Lima, on the central Peruvian coast (Stattersfield et al. 1998). It covers c.130,000 km2 and supports one of the highest totals of restricted-range bird species: 55 according to Stattersfield et al. (1998), or 56 following Best & Kessler (1995), the third largest number of endemic birds at any EBA globally. Within the EBA, in extreme north-west Peru, the Northwest Biosphere Reserve (NWBR) covers more than c.200,000 ha, with at least 96% forest cover (cf. Fig 38 in Best & Kessler 1995: 113, where all solid black on the left forms part of the NWBR). This statement is still valid today (Google Earth). The NWBR covers the Cerros de Amotape massif, a 130 km-long cordillera, 25–30 km wide at elevations of 250–1,600 m, running parallel to the main Andean chain (Palacios 1994). -

List of Rare, Threatened, and Endangered Animals of Maryland

List of Rare, Threatened, and Endangered Animals of Maryland December 2016 Maryland Wildlife and Heritage Service Natural Heritage Program Larry Hogan, Governor Mark Belton, Secretary Wildlife & Heritage Service Natural Heritage Program Tawes State Office Building, E-1 580 Taylor Avenue Annapolis, MD 21401 410-260-8540 Fax 410-260-8596 dnr.maryland.gov Additional Telephone Contact Information: Toll free in Maryland: 877-620-8DNR ext. 8540 OR Individual unit/program toll-free number Out of state call: 410-260-8540 Text Telephone (TTY) users call via the Maryland Relay The facilities and services of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources are available to all without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, age, national origin or physical or mental disability. This document is available in alternative format upon request from a qualified individual with disability. Cover photo: A mating pair of the Appalachian Jewelwing (Calopteryx angustipennis), a rare damselfly in Maryland. (Photo credit, James McCann) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Maryland Department of Natural Resources would like to express sincere appreciation to the many scientists and naturalists who willingly share information and provide their expertise to further our mission of conserving Maryland’s natural heritage. Publication of this list is made possible by taxpayer donations to Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay and Endangered Species Fund. Suggested citation: Maryland Natural Heritage Program. 2016. List of Rare, Threatened, and Endangered Animals of Maryland. Maryland Department of Natural Resources, 580 Taylor Avenue, Annapolis, MD 21401. 03-1272016-633. INTRODUCTION The following list comprises 514 native Maryland animals that are among the least understood, the rarest, and the most in need of conservation efforts. -

Rapid Biodiversity Assessment of Halcrow

E1751 RAPID BIODIVERSITY ASSESSMENT OF HALCROW AND GUYSUCO CONSERVANCIES Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL R EPORT Example: Densely populated JANUARY 2006 wooded reefs of low-medium height Photo: W. Prince Environmental Management Consultants Public Disclosure Authorized 60 Area H Ogle East Coast Demerara Cover photos: Waldyke Prince and Dr. Gary Clarke Top: Yellow Oriole Icterus nigrogularis Spectacled Caiman Caiman crocodilus Mabuya Skink Mabuya mabuya White Leaf Frog Hyla leucophyllata Bottom: Aerial view of the Skeldon Water Path bordering the Guysuco Conservancy Page 2 of 47 CONTENTS PAGES Executive Summary 6 1. INTRODUCTION 8 2. METHODOLOGY 2.1 Study Site 9 2.2 Schedule of Fieldwork 9 2.3 Vegetation Surveys 9 2.4 Faunal Surveys 11 2.5 Sampling Protocol 12 2.6 Collection of specimens 12 2.7 Photography 13 2.8 Data Analysis 13 3. RESULTS & DISCUSSION 3.1 Vegetation 14 3.2 Invertebrate fauna 19 3.3 Fish Fauna 20 3.4 Amphibian Fauna 21 3.5 Reptile Fauna 23 3.6 Mammal Fauna 24 3.7 Avifauna 26 3.8 Key Species and Habitats of Conservation Importance 32 3.9 Indicator Species 32 3.10 Summary of Flora and Fauna Species Diversity 32 3.11 Shift in Species Composition 33 4. CONSTRAINTS & LIMITATIONS 34 5. MANAGEMENT RECOMMENDATIONS 5.1 Biodiversity monitoring 35 5.2 Hunting 35 5.3 Cattle Ranching 35 5.4 Fire Control 35 5.5 Management of Watershed/Catchment Area 35 6. LITERATURE CITED 36 APPENDIX I Terms of Reference 37 APPENDIX II Schedule of Activities and Fieldwork 39 APPENDIX III Avifauna Transect Monitoring Datasheet 40 APPENDIX IV Images 42 Page 3 of 47 Table 1. -

Brazil: Southeast Atlantic Rainforest Cumulative Birdlist Column A: Number of Tours (Out of 12) on Which This Species Has Been

Brazil: Southeast Atlantic Rainforest Cumulative Birdlist Column A: Number of tours (out of 12) on which this species has been recorded Column B: Number of days this species was recorded on the 2018 tour Column C: Maximum daily count for this species on the 2018 tour Column D: H = heard only; N = Nesting x = non-avian species seen on 2018 tour A B C D 2 Solitary Tinamou 3 3 H Tinamus solitarius 12 Brown Tinamou 5 2 H Crypturellus obsoletus 11 Tataupa Tinamou Crypturellus tataupa 3 White-faced Whistling-Duck 1 20 Dendrocygna viduata 2 Black-bellied Whistling-Duck (autumnalis) 1 2 Dendrocygna autumnalis 1 Muscovy Duck 1 2 Cairina moschata 8 Brazilian Teal 1 2 Amazonetta brasiliensis 12 Dusky-legged Guan (Dusky-legged) 8 16 Penelope obscura 7 Spot-winged Wood-Quail 2 5 Odontophorus capueira 1 Least Grebe Tachybaptus dominicus 2 Rock Pigeon (Feral Pigeon) 7 31 Columba livia 11 Pale-vented Pigeon 3 4 Patagioenas cayennensis 11 Picazuro Pigeon 14 21 Patagioenas picazuro 11 Plumbeous Pigeon 5 3 Patagioenas plumbea 12 Ruddy Ground-Dove 9 20 Columbina talpacoti 1 Ruddy Quail-Dove Geotrygon montana 9 White-tipped Dove 2 4 Leptotila verreauxi 8 Gray-fronted Dove 3 1 Leptotila rufaxilla 5 Eared Dove 3 25 Zenaida auriculata 12 Guira Cuckoo 3 5 Guira guira 2 Greater Ani 1 20 Crotophaga major 12 Smooth-billed Ani 8 17 Crotophaga ani 10 Striped Cuckoo Tapera naevia 2 Pavonine Cuckoo 1 1 Dromococcyx pavoninus 12 Squirrel Cuckoo (Amazonian) 4 2 Piaya cayana 1 Dark-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus melacoryphus 2 Lesser Nighthawk Chordeiles acutipennis 2 Short-tailed Nighthawk (nattereri) 2 2 Lurocalis semitorquatus 3 Common Pauraque Nyctidromus albicollis ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. -

Icacos Bioblitz 2017 Final Report.Pdf

Final Report Contents Report Credits ....................................................................................................... iii Executive Summary ................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 2 Methods Plants......................................................................................................... 3 Birds .......................................................................................................... 3 Mammals .................................................................................................. 4 Reptiles and Amphibians .......................................................................... 5 Aquatic ...................................................................................................... 5 Terrestrial Invertebrates ........................................................................... 6 Fungi .......................................................................................................... 7 Microbiology ............................................................................................. 7 Results and Discussion Plants......................................................................................................... 8 Birds .......................................................................................................... 8 Mammals ................................................................................................. -

Juan Carlos Reboreda Vanina Dafne Fiorini · Diego Tomás Tuero Editors

Juan Carlos Reboreda Vanina Dafne Fiorini · Diego Tomás Tuero Editors Behavioral Ecology of Neotropical Birds Chapter 6 Obligate Brood Parasitism on Neotropical Birds Vanina Dafne Fiorini , María C. De Mársico, Cynthia A. Ursino, and Juan Carlos Reboreda 6.1 Introduction Obligate brood parasites do not build their nests nor do feed and take care of their nestlings. Instead, they lay their eggs in nests of individuals of other species (hosts) that rear the parasitic progeny. For behavioral ecologists interested in coevolution, obligate brood parasites are pearls of the avian world. These species represent only 1% of all the living avian species, and their peculiar reproductive strategy imposes on them permanent challenges for successful reproduction. At the same time, the hosts are under strong selective pressures to reduce the costs associated with para- sitism, such as the destruction of eggs by parasitic females and the potential fitness costs of rearing foreign nestlings. These selective pressures may result in parasites and hosts entering in a coevolutionary arms race, in which a broad range of defenses and counterdefenses can evolve. Females of most species of parasites have evolved behaviors such as rapid egg laying and damage of some of the host’s eggs when they visit the nest (Sealy et al. 1995; Soler and Martínez 2000; Fiorini et al. 2014). Reciprocally, as a first line of defense, hosts have evolved the ability to recognize and attack adult parasites (Feeney et al. 2012). Parasitic eggs typically hatch earlier than host eggs decreasing host hatching success and nestling survival (Reboreda et al. 2013), but several host species have evolved recognition and rejection of alien eggs, which in turn selected for the evolution of mimetic eggs in the parasite (Brooke and Davies 1988; Gibbs et al.