Police Interrogation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pragmatics of Powerlessness in Police Interrogation

Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons Faculty Scholarship 1-1-1993 In a Different Register: The Pragmatics of Powerlessness in Police Interrogation Janet Ainsworth Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/faculty Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Janet Ainsworth, In a Different Register: The Pragmatics of Powerlessness in Police Interrogation, 103 YALE L.J. 259 (1993). https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/faculty/287 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Articles In a Different Register: The Pragmatics of Powerlessness in Police Interrogation Janet E. Ainswortht CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................ 260 II. How WE Do THINGS WITH WORDS .............................. 264 A. Performative Speech Acts ................................. 264 B. Indirect Speech Acts as Performatives ......................... 267 C. ConversationalImplicature Modifying Literal Meaning ............. 268 H. GENDER AND LANGUAGE USAGE: A DIFFERENT REGISTER .............. 271 A. Characteristicsof the Female Register ........................ 275 1. Hedges ........................................... 276 2. Tag Questions ...................................... 277 t Associate Professor of Law, University of Puget Sound School of Law. B.A. Brandeis University, M.A. Yale University, J.D. Harvard Law School. My appreciative thanks go to Harriet Capron and Blain Johnson for their able research assistance. I am also indebted to Melinda Branscomb, Jacqueline Charlesworth, Annette Clark, Sid DeLong, Carol Eastman, Joel Handler, Robin Lakoff, Debbie Maranville, Chris Rideout, Kellye Testy, Austin Sarat, and David Skover for their helpful comments and suggestions. -

Interrogation Nation: Refugees and Spies in Cold War Germany Douglas Selvage / Office of the Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records

Interrogation Nation: Refugees and Spies in Cold War Germany Douglas Selvage / Office of the Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records In Interrogation Nation: Refugees and Spies in Cold War Germany, historian Keith R. Allen analyzes the “overlooked story of refugee screening in West Germany” (p. xv). Building upon his previous German-language study focused on such screening at the Marienfelde Refugee Center in West Berlin (Befragung - Überprüfung - Kontrolle: die Aufnahme von DDR- Flüchtlingen in West-Berlin bis 1961, Berlin: Ch. Links, 2013), Allen examines the places, personalities, and practices of refugee screening by the three Western Powers, as well as the German federal government, in West Berlin and throughout West Germany. The topic is particularly timely since, as Allen notes, many of “the screening programs established during the darkest days of the Cold War” (p. xv) continue today, although their targets have shifted. The current political debates about foreign and domestic intelligence activities in Germany, including the issue of refugee screening, echo earlier disputes from the years of the Bonn Republic. The central questions remain: To what extent have citizenship rights and the Federal Republic’s sovereignty been compromised by foreign and domestic intelligence agencies – largely with the consent of the German government – in the name of security? BERLINER KOLLEG KALTER KRIEG | BERLIN CENTER FOR COLD WAR STUDIES 2017 Douglas Selvage Interrogation Nation Allen divides his study into three parts. In Part I, he focuses on “places” – the various sites in occupied West Berlin and western Germany where refugees were interrogated. He sifts through the alphabet soup of acronyms of US, British, French, and eventually West German civilian and military intelligence services and deciphers the cover names of the institutions and locations at which they engaged in screening activities during the Cold War and beyond. -

Ten Strategies of a World-Class Cybersecurity Operations Center Conveys MITRE’S Expertise on Accumulated Expertise on Enterprise-Grade Computer Network Defense

Bleed rule--remove from file Bleed rule--remove from file MITRE’s accumulated Ten Strategies of a World-Class Cybersecurity Operations Center conveys MITRE’s expertise on accumulated expertise on enterprise-grade computer network defense. It covers ten key qualities enterprise- grade of leading Cybersecurity Operations Centers (CSOCs), ranging from their structure and organization, computer MITRE network to processes that best enable effective and efficient operations, to approaches that extract maximum defense Ten Strategies of a World-Class value from CSOC technology investments. This book offers perspective and context for key decision Cybersecurity Operations Center points in structuring a CSOC and shows how to: • Find the right size and structure for the CSOC team Cybersecurity Operations Center a World-Class of Strategies Ten The MITRE Corporation is • Achieve effective placement within a larger organization that a not-for-profit organization enables CSOC operations that operates federally funded • Attract, retain, and grow the right staff and skills research and development • Prepare the CSOC team, technologies, and processes for agile, centers (FFRDCs). FFRDCs threat-based response are unique organizations that • Architect for large-scale data collection and analysis with a assist the U.S. government with limited budget scientific research and analysis, • Prioritize sensor placement and data feed choices across development and acquisition, enteprise systems, enclaves, networks, and perimeters and systems engineering and integration. We’re proud to have If you manage, work in, or are standing up a CSOC, this book is for you. served the public interest for It is also available on MITRE’s website, www.mitre.org. more than 50 years. -

Tradecraft Primer: a Framework for Aspiring Interrogators

Journal of Strategic Security Volume 9 Number 4 Volume 9, No. 4, Special Issue Winter 2016: Understanding and Article 11 Resolving Complex Strategic Security Issues Tradecraft Primer: A Framework for Aspiring Interrogators. By Paul Charles Topalian. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2016. Mark J. Roberts Subject Matter Expert Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss pp. 139-141 Recommended Citation Roberts, Mark J.. "Tradecraft Primer: A Framework for Aspiring Interrogators. By Paul Charles Topalian. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2016.." Journal of Strategic Security 9, no. 4 (2016) : 139-141. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.9.4.1576 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol9/iss4/11 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Strategic Security by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tradecraft Primer: A Framework for Aspiring Interrogators. By Paul Charles Topalian. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2016. This book review is available in Journal of Strategic Security: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/ vol9/iss4/11 Roberts: Tradecraft Primer: A Framework for Aspiring Interrogators. By Pau Tradecraft Primer: A Framework for Aspiring Interrogators. By Paul Charles Topalian. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2016. ISBN 978-1-4987-5114-8. Photographs. Figures. Sources cited. Index. Pp. xv, 140. $59.95. Interrogation is a word fraught with many inferences and implications. Revelations of waterboarding, incidents in Abu Graib and Guantanamo, and allegations of police impropriety in obtaining confessions have all cast the topic in a negative light in recent years. -

Perspectives on Enhanced Interrogation Techniques

Perspectives on Enhanced Interrogation Techniques Anne Daugherty Miles Analyst in Intelligence and National Security Policy July 9, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43906 Perspectives on Enhanced Interrogation Techniques Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Perspectives on EITs and Torture..................................................................................................... 7 Perspectives on EITs and Values .................................................................................................... 10 Perspectives on EITs and Effectiveness ......................................................................................... 11 Additional Steps ............................................................................................................................. 14 Appendixes Appendix A. CIA Standard Interrogation Techniques (SITs) ........................................................ 15 Appendix B. CIA Enhanced Interrogation Techniques (EITs) ....................................................... 17 Contacts Author Contact Information........................................................................................................... 18 Congressional Research Service Perspectives on Enhanced Interrogation -

Espionage and Intelligence Gathering Other Books in the Current Controversies Series

Espionage and Intelligence Gathering Other books in the Current Controversies series: The Abortion Controversy Issues in Adoption Alcoholism Marriage and Divorce Assisted Suicide Medical Ethics Biodiversity Mental Health Capital Punishment The Middle East Censorship Minorities Child Abuse Nationalism and Ethnic Civil Liberties Conflict Computers and Society Native American Rights Conserving the Environment Police Brutality Crime Politicians and Ethics Developing Nations Pollution The Disabled Prisons Drug Abuse Racism Drug Legalization The Rights of Animals Drug Trafficking Sexual Harassment Ethics Sexually Transmitted Diseases Family Violence Smoking Free Speech Suicide Garbage and Waste Teen Addiction Gay Rights Teen Pregnancy and Parenting Genetic Engineering Teens and Alcohol Guns and Violence The Terrorist Attack on Hate Crimes America Homosexuality Urban Terrorism Illegal Drugs Violence Against Women Illegal Immigration Violence in the Media The Information Age Women in the Military Interventionism Youth Violence Espionage and Intelligence Gathering Louise I. Gerdes, Book Editor Daniel Leone,President Bonnie Szumski, Publisher Scott Barbour, Managing Editor Helen Cothran, Senior Editor CURRENT CONTROVERSIES San Diego • Detroit • New York • San Francisco • Cleveland New Haven, Conn. • Waterville, Maine • London • Munich © 2004 by Greenhaven Press. Greenhaven Press is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Greenhaven® and Thomson Learning™ are trademarks used herein under license. For more information, contact Greenhaven Press 27500 Drake Rd. Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535 Or you can visit our Internet site at http://www.gale.com ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems—without the written permission of the publisher. -

Digital Forensics: Methods and Tools for Retrieval and Analysis of Security

NORGES TEKNISK-NATURVITENSKAPELIGE UNIVERSITET FAKULTET FOR INFORMASJONSTEKNOLOGI, MATEMATIKK OG ELEKTROTEKNIKK MASTEROPPGAVE Kandidatens navn: Andreas Grytting Furuseth Fag: Datateknikk Oppgavens tittel (norsk): Oppgavens tittel (engelsk): Digital Forensics: Methods and tools for re- trieval and analysis of security credentials and hidden data. Oppgavens tekst: The student is to study methods and tools for retrieval and analysis of security credentials and hidden data from different media (including hard disks, smart cards, and network traffic). The student will perform prac- tical experiments using forensic tools and attempt to identify possibilities for automating evidence analysis with respect to e.g. passwords, crypto- graphic keys, encrypted data, steganography, etc. The student will also study the correlation of identified security credentials from different media in order to improve the possibility of successful identification and decryp- tion of encrypted data. Oppgaven gitt: 28. Januar 2005 Besvarelsen leveres innen: 1. August 2005 Besvarelsen levert: 15. Juli 2005 Utført ved: Institutt for datateknikk og informasjonsvitenskap Q2S - Centre for Quantifiable Quality of Service in Communication Systems Veileder: Andr´e Arnes˚ Trondheim, 15. Juli 2005 Torbjørn Skramstad Faglærer Abstract Steganography is about information hiding; to communicate securely or conceal the existence of certain data. The possibilities provided by steganography are appealing to criminals and law enforcement need to be up-to-date. This master thesis provides investigators with insight into methods and tools for steganog- raphy. Steganalysis is the process of detecting messages hidden using steganography and is examined together with methods to detect steganography usage. This report proposes digital forensic methods for retrieval and analysis of steganog- raphy during a digital investigation. -

Psychological Perspectives on Interrogation Research-Article7065152017

PPSXXX10.1177/1745691617706515Vrij et al.Psychological Perspectives on Interrogation 706515research-article2017 Perspectives on Psychological Science 2017, Vol. 12(6) 927 –955 Psychological Perspectives on © The Author(s) 2017 Reprints and permissions: Interrogation sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617706515 10.1177/1745691617706515 www.psychologicalscience.org/PPS Aldert Vrij1, Christian A. Meissner2, Ronald P. Fisher3, Saul M. Kassin4, Charles A. Morgan III5, and Steven M. Kleinman6 1University of Portsmouth, 2Iowa State University, 3Florida International University, 4John Jay College of Criminal Justice, 5University of New Haven, and 6Operational Sciences International Abstract Proponents of “enhanced interrogation techniques” in the United States have claimed that such methods are necessary for obtaining information from uncooperative terrorism subjects. In the present article, we offer an informed, academic perspective on such claims. Psychological theory and research shows that harsh interrogation methods are ineffective. First, they are likely to increase resistance by the subject rather than facilitate cooperation. Second, the threatening and adversarial nature of harsh interrogation is often inimical to the goal of facilitating the retrieval of information from memory and therefore reduces the likelihood that a subject will provide reports that are extensive, detailed, and accurate. Third, harsh interrogation methods make lie detection difficult. Analyzing speech content and eliciting verifiable details are the most reliable cues to assessing credibility; however, to elicit such cues subjects must be encouraged to provide extensive narratives, something that does not occur in harsh interrogations. Evidence is accumulating for the effectiveness of rapport-based information-gathering approaches as an alternative to harsh interrogations. Such approaches promote cooperation, enhance recall of relevant and reliable information, and facilitate assessments of credibility. -

Industrial Espionage from AFIO's the INTELLIGENCER

Association of Former Intelligence Officers 7700 Leesburg Pike, Suite 324 From AFIO's The Intelligencer Falls Church, Virginia 22043 Journal of U.S. Intelligence Studies Web: www.afio.com, E-mail: [email protected] • A trained foreign agent, who had been in the Volume 22 • Number 1 • $15 single copy price Spring 2016 ©2016, AFIO United States for more than 20 years and had become a citizen, suddenly was “activated” by his controllers in Asia and given a “shopping list” of technical information to obtain, and then proceeded to steal massive amounts of technical information from his company on the next generation of nuclear submarines being constructed for the US Navy. GUIDE TO THE STUDY OF INTELLIGENCE • An employee working for a large US manufac- turing company decided to strike out and form his own company, but first stole all of the nec- essary technical information to manufacture competing high-technology products. • A country that is an enemy (or “strategic com- petitor”) to the United States sent a number of Industrial Espionage “illegals” into various companies to systemat- ically report on all technical developments and strategies of the targeted US companies. by Edward M. Roche, PhD, JD • A major hotel chain vice president decided that he was not being paid enough and took all of No information I received was the result of spying. the records regarding the development of a Everything was given to me in casual conversations new hotel concept to a competitor, where he got without coercion. better pay and a substantial promotion. 1 — Richard Sorge, interrogation at Sugamo Prison. -

Guide to Computer Forensics and Investigations Fourth Edition

Guide to Computer Forensics and Investigations Fourth Edition Chapter 2 Understanding Computer Investigations Objectives • Explain how to prepare a computer investigation • Apply a systematic approach to an investigation • Describe procedures for corporate high-tech investigations Guide to Computer Forensics and Investigations 2 Objectives (continued) • Explain requirements for data recovery workstations and software • Describe how to conduct an investigation • Explain how to complete and critique a case Guide to Computer Forensics and Investigations 3 Preparing a Computer Investigation • Role of computer forensics professional is to gather evidence to prove that a suspect committed a crime or violated a company policy • Collect evidence that can be offered in court or at a corporate inquiry – Investigate the suspect’s computer – Preserve the evidence on a different computer Guide to Computer Forensics and Investigations 4 Preparing a Computer Investigation (continued) • Follow an accepted procedure to prepare a case • Chain of custody – Route the evidence takes from the time you find it until the case is closed or goes to court Guide to Computer Forensics and Investigations 5 An Overview of a Computer Crime • Computers can contain information that helps law enforcement determine: – Chain of events leading to a crime – Evidence that can lead to a conviction • Law enforcement officers should follow proper procedure when acquiring the evidence – Digital evidence can be easily altered by an overeager investigator • Information on hard disks -

Human Intelligence Collector Operations, FM 2-22.3

*FM 2-22.3 (FM 34-52) Field Manual Headquarters No. 2-22.3 Department of the Army Washington, DC, 6 September 2006 Human Intelligence Collector Operations Contents Page PREFACE vi PART ONE HUMINT SUPPORT, PLANNING, AND MANAGEMENT Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1-1 Intelligence Battlefield Operating System 1-1 Intelligence Process 1-1 Human Intelligence 1-4 HUMINT Source 1-4 HUMINT Collection and Related Activities 1-7 Traits of a HUMINT Collector 1-1 0 Required Areas of Knowledge 1-12 Capabilities and Limitations 1-13 Chapter 2 HUMAN INTELLIGENCE STRUCTURE 2-1 Organization and Structure 2-1 HUMINT Control Organizations 2-2 HUMINT Analysis and Production Organizations 2-6 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. NOTE: All previous versions of this manual are obsolete. This document is identical in content to the version dated 6 September 2006. All previous versions of this manual should be destroyed in accordance with appropriate Army policies and reyulations. 'This publication supersedeJyM 34-52, 28 September 1992, and ST 2-22.7, Tactical Human Intelligence and Counterintelligence Operations, April 2002. PENTAGON LmRARY \" "j MrtlTARY OOCUMENTI WASHINGTON, DC 20310 6 September 2006 FM 2-22.3 FM 2-22.3 ------------ Chapter 3 HUMINT IN SUPPORT OF ARMY OPERATIONS 3-1 Offensive Operations ...............................•............................................................ 3-1 Defensive Operations 3-2 Stability and Reconstruction Operations 3-3 Civil Support Operations 3-7 Military Operations in Urban Environment.. 3-8 HUMINT Collection Environments 3-8 EAC HUMINT 3-9 Joint, Combined, and DOD HUMINT Organizations 3-10 Chapter 4 HUMINT OPERATIONS PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT .4-1 HUMINT and the Operations Process .4-1 HUMINT Command and Control .4-3 Technical Control. -

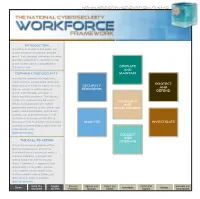

The National Cybersecurity Workforce Framework (“The Framework”) to Provide a Analyze Investigate Common Understanding of and Lexicon for Cybersecurity Work

NATIONAL INITIATIVE FOR CYBERSECURITY EDUCATION (NICE) introduction The ability of academia and public and private employers to prepare, educate, recruit, train, develop, and retain a diverse, to our nation’s security and prosperity. [full text version] operate and defining cybersecurity maintain Defining the cybersecurity population using common, standardized labels and protect definitions is an essential step in ensuring securely and provision that our country is able to educate, defend recruit, train, develop, and retain a highly-qualified workforce. The National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education oversight (NICE), in collaboration with federal and government agencies, public and private development experts and organizations, and industry partners, has published version 1.0 of the National Cybersecurity Workforce Framework (“the Framework”) to provide a analyze investigate common understanding of and lexicon for cybersecurity work. [full text version] collect and The Call To ACTION operate Only in the universal adoption of the National Cybersecurity Workforce Framework can we ensure our nation’s enduring capability to prevent and defend against an ever-increasing threat. Therefore, it is imperative that organizations in the public, private, and academic sectors begin using the Framework’s lexicon (labels and definitions) as soon as possible. [full text version] Using This Sample Securely Operate and Protect and Collect and Oversight and Home Document Job Titles Provision Maintain Defend Investigate Operate Analyze Development NATIONAL INITIATIVE FOR CYBERSECURITY EDUCATION (NICE) introduction The ability of academia and public and private employers to These challenges are exacerbated by the unique aspects of prepare, educate, recruit, train, develop, and retain a highly-qualified cybersecurity work. For example, the cybersecurity workforce must cybersecurity workforce is vital to our nation’s security and prosperity.