Naw, I'm Buried in the Ground

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lost Prince,The

THE LOST PRINCE Francis Hodgson Burnett CONTENTS I The New Lodgers at No. 7 Philibert Place II A Young Citizen of the World III The Legend of the Lost Prince IV The Rat V ``Silence Is Still the Order'' VI The Drill and the Secret Party VII ``The Lamp Is Lighted!'' VIII An Exciting Game IX ``It Is Not a Game'' X The Rat-and Samavia XI Come with Me XII Only Two Boys XIII Loristan Attends a Drill of the Squad XIV Marco Does Not Answer XV A Sound in a Dream XVI The Rat to the Rescue XVII ``It Is a Very Bad Sign'' XVIII ``Cities and Faces'' XIX ``That Is One!'' XX Marco Goes to the Opera XXI ``Help!'' XXII A Night Vigil XXIII The Silver Horn XXIV ``How Shall We Find Him? XXV A Voice in the Night XXVI Across the Frontier XXVII ``It is the Lost Prince! It Is Ivor!'' XXVIII ``Extra! Extra! Extra!'' XXIX 'Twixt Night and Morning XXX The Game Is at an End XXXI ``The Son of Stefan Loristan'' THE LOST PRINCE I THE NEW LODGERS AT NO. 7 PHILIBERT PLACE There are many dreary and dingy rows of ugly houses in certain parts of London, but there certainly could not be any row more ugly or dingier than Philibert Place. There were stories that it had once been more attractive, but that had been so long ago that no one remembered the time. It stood back in its gloomy, narrow strips of uncared-for, smoky gardens, whose broken iron railings were supposed to protect it from the surging traffic of a road which was always roaring with the rattle of busses, cabs, drays, and vans, and the passing of people who were shabbily dressed and looked as if they were either going to hard work or coming from it, or hurrying to see if they could find some of it to do to keep themselves from going hungry. -

Lps Page 1 -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

LPs ARTIST TITLE LABEL COVER RECORD PRICE 10 CC SHEET MUSIC UK M M 5 2 LUTES MUSIC IN THE WORLD OF ISLAM TANGENT M M 10 25 YEARS OF ROYAL AT LONDON PALLADIUM GF C RICHARD +E PYE 2LPS 1973 M EX 20 VARIETY JOHN+SHADOWS 4 INSTANTS DISCOTHEQUE SOCITY EX- EX 20 4TH IRISH FOLK FESTIVAL ON THE ROAD 2LP GERMANY GF INTRERCORD EX M 10 5 FOLKFESTIVAL AUF DER LENZBURG SWISS CLEVES M M 15 5 PENNY PIECE BOTH SIDES OF 5 PENNY EMI M M 7 5 ROYALES LAUNDROMAT BLUES USA REISSUE APOLLO M M 7 5 TH DIMENSION REFLECTION NEW ZEALAND SBLL 6065 EX EX 6 5TH DIMENSION EARTHBOUND ABC M M 10 5TH DIMENSION AGE OF AQUARIUS LIBERTY M M 12 5TH DIMENSION PORTRAIT BELL EX EX- 5 75 YEARS OF EMI -A VOICE WITH PINK FLOYD 2LPS BOX SET EMI EMS SP 75 M M 40 TO remember A AUSTR MUSICS FROM HOLY GROUND LIM ED NO 25 HG 113 M M 35 A BAND CALLED O OASIS EPIC M M 6 A C D C BACK IN BLACK INNER K 50735 M NM 10 A C D C HIGHWAY TO HELL K 50628 M NM 10 A D 33 SAME RELIGIOUS FOLK GOOD FEMALE ERASE NM NM 25 VOCALS A DEMODISC FOR STEREO A GREAT TRACK BY MIKE VICKERS ORGAN EXP70 M M 25 SOUND DANCER A FEAST OF IRISH FOLK SAME IRISH PRESS POLYDOR EX M 5 A J WEBBER SAME ANCHOR M M 7 A PEACOCK P BLEY DUEL UNITY FREEDOM EX M 20 A PINCH OF SALT WITH SHIRLEY COLLINS 1960 HMV NM NM 35 A PINCH OF SALT SAME S COLLINS HMV EX EX 30 A PROSPECT OF SCOTLAND SAME TOPIC M M 5 A SONG WRITING TEAM NOT FOR SALE LP FOR YOUR EYES ONLY PRIVATE M M 15 A T WELLS SINGING SO ALONE PRIVATE YPRX 2246 M M 20 A TASTE OF TYKE UGH MAGNUM EX EX 12 A TASTE OF TYKE SAME MAGNUM VG+ VG+ 8 ABBA GREATEST HITS FRANCE VG 405 EX EX -

Rolling Stones Singles Discography 1964‐1970

Rolling Stones Singles Discography 1964‐1970 Regular‐Issue Singles “I Wanna Be Your Man”/ “Stoned” London 45‐LON‐9641 February 22, 1964. Label 61wdj White label with script London. Pressed by Monarch, job number Δ 51259. Label61dj White label with deep purple bar across label and gray ovals. Columbia Bridgeport (V suffix) Columbia Terre Haute Label61 White label with purple bar across label and gray ovals. Pressed by Columbia Bridgeport. Aside from the promotional copy having a stamping of February 17, 1964, there are other factors pointing to a date in mid‐to‐late February for the release of this single. Singles having Monarch numbers around this one were released at about the same time. “The Shoop Shoop Song” by Betty Everett, Δ 51253, was released the week of February 22nd and debuted on the 29th. Ray Charles’ “Baby Don’t You Cry” was previewed on February 15th, released near the end of the month, and debuted on the Billboard chart on March 14th; its Monarch number was Δ 51264. That information coincides with the fact that the Rolling Stones single was reviewed on February 22nd, 1964 (on page 22). “Not Fade Away”/ “I Wanna Be Your Man” London 45‐LON‐9657 March 28, 1964. Label 61wdj White label with script London. Pressed by Monarch, A‐side job number Δ 51659. Label61dj White label with deep purple bar across label and gray ovals. Columbia Terre Haute Label61 White label with purple bar across label and gray ovals. March 28, 1964, to March, 1965. Monarch (i) Monarch (ii) Columbia Terre Haute RCA Rockaway Columbia Pitman? Picture Sleeve Jan Davis’ “The Fugitive,” Δ 51671, was first mentioned in BB on March 28th. -

SIR EDWARD ELGAR (1857-1934) AMANDA ROOCROFT � KONRAD JARNOT � REINILD MEES Complete Songs for Voice and Piano Vol

28610ElgarMeesbooklet 12-11-2009 12:11 Pagina 1 CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 28610 SIR EDWARD ELGAR (1857-1934) AMANDA ROOCROFT KONRAD JARNOT REINILD MEES Complete Songs for voice and piano vol. 2 28610ElgarMeesbooklet 12-11-2009 12:11 Pagina 2 As we noted in the first volume of this survey publishers of the day. A Soldier’s Song, styled of Elgar’s songs, like most composers his first as ‘Op 5’ dates from 1884 and although it was attempts at composition were with anthems sung at the Worcester Glee Club in March that and small chamber and piano pieces, though year it had to wait for publication until 1890 unlike many young composers of his day, when it appeared in The Magazine of Music – strangely Elgar wrote few songs until his and 1903, when renamed A War Song, Boosey various love affairs from his mid-twenties on- took it on, doubtless with the public’s wards. Elgar’s early life as a composer was one preoccupation with the Boer War in mind. of constantly hawking salon music and Another American, Colonel John Hay popular short pieces round publishers – a provided the words for Through the Long situation that gradually changed in the 1890s Days, which dated ‘Gigglewycke (his friend as his early works for chorus and orchestra Charles William Buck’s Yorkshire home) on were heard. But it took Elgar a long time to 10 Aug 1885 was sung in London at a St become established, the Enigma Variations James’s Hall ballad concert in February 1887 only appearing when he was 41. -

The Rolling Stones Complete Recording Sessions 1962 - 2020 Martin Elliott Session Tracks Appendix

THE ROLLING STONES COMPLETE RECORDING SESSIONS 1962 - 2020 MARTIN ELLIOTT SESSION TRACKS APPENDIX * Not Officially Released Tracks Tracks in brackets are rumoured track names. The end number in brackets is where to find the entry in the 2012 book where it has changed. 1962 January - March 1962 Bexleyheath, Kent, England. S0001. Around And Around (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (1.21) * S0002. Little Queenie (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (4.32) * (a) Alternative Take (4.11) S0003. Beautiful Delilah (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.58) * (a) Alternative Take (2.18) S0004. La Bamba (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (0.18) * S0005. Go On To School (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.02) * S0006. I'm Left, You're Right, She's Gone (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.31) * S0007. Down The Road Apiece (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.12) * S0008. Don't Stay Out All Night (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.30) * S0009. I Ain't Got You (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.00) * S0010. Johnny B. Goode (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.24) * S0011. Reelin' And A Rockin' (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) * S0012. Bright Lights, Big City (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) * 27 October 1962 Curly Clayton Sound Studios, Highbury, London, England. S0013. You Can't Judge A Book By The Cover (0.36) * S0014. Soon Forgotten * S0015. Close Together * 1963 11 March 1963 IBC Studios, London, England. S0016. Diddley Daddy (2.38) S0017. Road Runner (3.04) S0018. I Want To Be Loved I (2.02) S0019. -

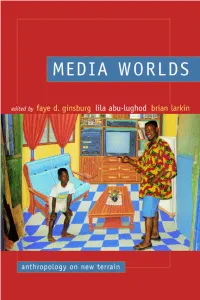

Media Worlds : Anthropology on New Terrain / Edited by Faye D

Media Worlds Media Worlds Anthropology on New Terrain EDITED BY Faye D. Ginsburg, Lila Abu-Lughod, and Brian Larkin UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2002 by the Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Media worlds : anthropology on new terrain / edited by Faye D. Ginsburg, Lila Abu-Lughod, and Brian Larkin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-520-22448-5 (Cloth : alk. paper)— isbn 0-520-23231-3 (Paper : alk. paper) 1. Mass media and culture. I. Ginsburg, Faye D. II. Abu-Lughod, Lila. III. Larkin, Brian. P94.6 .M426 2002 302.23—dc21 2002002312 Manufactured in the United States of America 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 987654 321 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum require- ments of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).8 For Annie, Sinéad, Adrian, Justine, and Samantha, whose media worlds will be even fuller than ours. It is often said that [media have] altered our world. In the same way, people often speak of a new world, a new society, a new phase of history, being created—“brought about”—by this or that new technology: the steam engine, the automobile, the atomic bomb. Most of us know what is generally implied when such things are said. But this may be the central difficulty: that we have got so used to statements of this general kind, in our most ordinary discussions, that we fail to realise their specific meanings. -

The Rolling Stones Complete Recording Sessions 1962 - 2020 Martin Elliott Also Known As Index

THE ROLLING STONES COMPLETE RECORDING SESSIONS 1962 - 2020 MARTIN ELLIOTT ALSO KNOWN AS INDEX To assist with track identities, I have produced this new index which lists the alternative titles of tracks along with their more commonly known as name. The number where the track is featured within the 2012 book is also shown. 1-2-3-4 Covered In Bruises 724 2120 South Michigan Avenue (And Muddy Came Too) 2120 South Michigan Avenue 131 9/11 Hurricane Hurricane 1350 A Mess With Fire Play With Fire 201 A Right Charlie Alright Charlie 1081 Acid In The Grass In Another Land 351 After Five Citadel 355 Aftermath Mr Spector And Mr Pitney Came Too 78 Aftermath 2000 Light Years From Home 350 Again And Again And Again Guitar Lesson 822 Ain't Gonna Lie I'm Not Signifying 528 Ain't No Use In Crying No Use In Crying 849 Aladdin Stomp So Divine (Aladdin Story) 432 Aladdin Story So Divine (Aladdin Story) 432 All Mixed Up I’m A Little Mixed Up 921 All Part Of The Act All Sold Out 308 All Together Sing This All Together 360 All Together Sing This All Together (See What Happens) 361 All Your Love All Of Your Love And I Know I Love You Too Much 713 And I Was A Country Boy I'm A Country Boy 430 And The Rolling Stones Met Phil And Gene Andrew's Blues 77 Anybody Seen My Baby? (Soul Solution Vocal Dub) Anybody Seen My Baby? (Soul Solution Remix) 1265 As Tears Go By As Time Goes By 87 As Tears Go By Con Le Mie Lacrime 300, 1496 Avant Garde Trouble In Mind 336 Back On The Streets Again Eliza 934 Back To The Country Cellophane Trousers 648 Because? Just Because Bedroom -

The Rolling Stones the Ultimate Guide Contents

The Rolling Stones The Ultimate Guide Contents 1 The Rolling Stones 1 1.1 History .................................................. 2 1.1.1 Early history ........................................... 2 1.1.2 1962–1964: Building a following ................................ 2 1.1.3 1965–1967: Height of fame ................................... 4 1.1.4 1968–1972: “Back to basics” ................................... 7 1.1.5 1972–1977: Mid '70s ...................................... 9 1.1.6 1978–1982: Commercial peak .................................. 10 1.1.7 1983–1988: Band turmoil and solo efforts ............................ 11 1.1.8 1989–1999: Comeback, return to popularity, and record-breaking tours ............ 12 1.1.9 2000–2011: A Bigger Bang and continued success ........................ 13 1.1.10 2012–present: 50th anniversary and covers album ........................ 14 1.2 Musical development ........................................... 15 1.3 Legacy .................................................. 17 1.4 Tours ................................................... 17 1.5 Band members .............................................. 18 1.5.1 Timeline ............................................. 19 1.6 Discography ................................................ 19 1.7 See also .................................................. 20 1.8 References ................................................ 20 1.8.1 Footnotes ............................................. 20 1.8.2 Sources .............................................. 33 1.9 Further -

A 650WER Went Forth to SOW

1852 Centennial 1952 '74 *meek, INSTRUCTOR A 650WER Went Forth to SOW By MRS. WALTER DOHERTY WO young gospel workers and their It was in the early part of the twentieth and that night, when the boys were home Twives were traveling to their new dis- century. The faithful colporteur had left from their logging and the mother was trict of labor. With them in the car sat wife and family many days behind and ready to listen, the sower produced his the conference president. The midsummer gone forth to sow the precious seeds of the book, The Great Controversy Between sun beat down cruelly on the red dusty truth that is so dear to him. Every day he Christ and Satan. The young woman be- plains, and swirls of choking dust en- walked many weary miles, finding here came intensely interested. To the disgust veloped the car. Grasshoppers committed and there, beside the ocean or on the lake of her mother and four brothers she suicide on the windshield, and others flew shore, homes where the message of a ordered the book and began to read. She in through the windows to crawl on the soon-coming Savioiir that he carries is heard God's voice and decided to obey occupants of the car. Desert and heat received. His commands. Her family disowned her and unpromising countryside! Not alto- One evening just at dusk he found his after much ridicule and effort to persuade gether an inviting field of labor. way to a humble cottage door, and as he her to give up her faith. -

CHARLIE WATTS 1941 to 2021 the Rhythmic Force Behind the Greatest Rock and Roll Band in the World

CHARLIE WATTS 1941 to 2021 The rhythmic force behind the greatest rock and roll band in the world. The Rolling Stones were a force of nature when they were in the studio during their artistic peak in the 60s and 70s. Their albums through the 60s produced masterpieces with Out Of Our Heads (1965 being their first self-penned), Aftermath (1966 which indicated song writing prowess) and culminating in Beggars Banquet and Let It Bleed (1968 and 1969 respectively – pure magnificence). Sure, we had several huge selling singles in between. A run of releases from 1965 to 1969 produced Satisfaction, Get Off Of My Cloud, 19th Nervous Breakdown, Paint It, Black, Mother’s Little Helper, Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing In The Shadow?, Let’s Spend The Night Together, We Love You, In Another Land, She’s A Rainbow, Jumpin’ Jack Flash, Street Fighting Man and Honky Tonk Women. Their incredible 70s album run continued with Sticky Fingers, Exile On Main St., Goats Head Soup, It’s Only Rock n’ Roll, Black and Blue and Some Girls. The glue that provided their success was the rhythm unit of Charlie Watts and Bill Wyman. They dictated the back beat and gave the roll to the band’s rock. According to Charlie, the Rolling Stones meant nothing to him – that was Mick Jagger and Keith Richards. They were the artistic front while the sparkles were the founders of the band Brian Jones and Ian Stewart not to mention Nicky Hopkins, Mick Taylor and Ron Wood. There are of course significant other contributors – Andrew Oldham, Jack Nitzsche, Glyn Johns, Dave Hassinger, Jimmy Miller, Bobby Keys, Billy Preston and Andy Johns – and yes, I am sure I have missed important others. -

Property from Bill Wyman and His Rolling Stones Archive Press Release

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS: PROPERTY FROM BILL WYMAN AND HIS ROLLING STONES ARCHIVE PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: PROPERTY FROM BILL WYMAN AND HIS ROLLING STONES ARCHIVE COURTESY OF RIPPLE PRODUCTIONS LIMITED NEW DATES ANNOUNCED: FRIDAY 11 , SATURDAY 12 & SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 2020 AT JULIEN’S AUCTIONS BEVERLY HILLS THE LEGENDARY BASSIST AND FOUNDING MEMBER’S RENOWNED ARCHIVE – CONSIDERED THE MOST IMPORTANT COLLECTION OF ARTIFACTS AND MEMORABILIA DOCUMENTING THE ROLLING STONES’ HISTORY AND LEGACY AS ONE OF THE MOST INFLUENTIAL BANDS OF THE 20TH CENTURY – WILL BE OFFERED FOR THE FIRST TIME AT AUCTION Highlights include: Wyman’s historic 1962 VOX AC30 ‘Normal’ model amplifier which famously clinched his audition for the legendary British rock band, Wyman’s guitar collection used on the band’s career defining performances, tours and recording sessions, including his 1969 Fender Mustang Bass Competition Orange, 1978 Travis Bean Custom Short Scale Bass, 1974 Dan Armstrong Prototype Bass, 1981 black Steinberger Custom Short-Scale XL-Series Bass, Framus Star Bass model 5/150 Black Rose Sunburst, Brian Jones’ Rock and Roll Circus 1968 Gibson Les Paul Standard Model Gold Top and more Awards, Instruments, Concert Posters, Stage Worn Ensembles, Photographs, Correspondence, Production Documents and Other Ephemera to Rock the Auction Stage and U.S. Exhibition September 7 - September 11 in Beverly Hills A Portion of the Proceeds of the Auction to Benefit The Prince’s Trust, Macmillan Cancer Support and CCMI (Central Caribbean Marine Institute) SEPTEMBER 11TH, 12TH AND 13TH, 2020 Beverly Hills, California – (April 22, 2020) – Julien’s Auctions, the auction house to the stars, announced today the new dates of property from BILL WYMAN AND HIS ROLLING STONES ARCHIVE COURTESY OF RIPPLE PRODUCTIONS LIMITED taking place Friday 11th, Saturday 12th and Sunday, September 13th, 2020 live in Beverly Hills and online at www.juliensauctions.com. -

Revolutionary Writing in Aimé Césaire and Ghassan

Combat in “A World not for Us:” Revolutionary Writing in Aimé Césaire and Ghassan Kanafani By Amirah Mohammad Silmi A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Rhetoric in the Graduate Division Of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Trinh, T. Minh-ha, Chair. Professor Pheng Cheah Professor Donna V. Jones Professor Samera Esmeir Summer 2016 1 Abstract Combat in a “World Not for Us:” Revolutionary Writing in Aimé Césaire and Ghassan Kanafani By Amirah Mohammad Silmi Doctor of Philosophy in Rhetoric University of California, Berkeley Professor Trinh, T. Minh-ha, Chair This dissertation explores how the writings of two colonized writers, Aimé Césaire and Ghassan Kanafani, constitute in themselves acts of freedom by combatting a rationalized knowledge that determines what is to be known and what is to be unknown. The dissertation underlines how an act of freedom, as exemplified by the texts of both writers, entails courage in confronting the cruel in a colonized life, as it entails the bravery of taking the risk of tearing open shields of concealment and denial. The dissertation is not an investigation of the similarities and/or differences between the two writers. It is rather an “excavation” of their texts for points where there remain fragments hidden in margins or buried in gaps that point to other lives, other modes of being, in which the colonized share more than their colonized being. The dissertation is thus a relating of their writings, it is a linking, beyond classificatory categories, of the spaces where their writings mobilize and evoke each other, a search for spaces where they resonate.