Elements of Baroque Performance Style Applied to a Popular Piece of J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

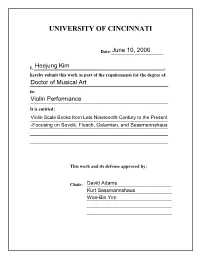

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ ViolinScaleBooks fromLateNineteenth-Centurytothe Present -FocusingonSevcik,Flesch,Galamian,andSassmannshaus Adocumentsubmittedtothe DivisionofGraduateStudiesandResearchofthe UniversityofCincinnati Inpartialfulfillmentoftherequirementsforthedegreeof DOCTORAL OFMUSICALARTS inViolinPerformance 2006 by HeejungKim B.M.,Seoul NationalUniversity,1995 M.M.,TheUniversityof Cincinnati,1999 Advisor:DavidAdams Readers:KurtSassmannshaus Won-BinYim ABSTRACT Violinists usuallystart practicesessionswithscale books,andtheyknowthe importanceofthem asatechnical grounding.However,performersandstudents generallyhavelittleinformation onhowscale bookshave beendevelopedandwhat detailsaredifferentamongmanyscale books.Anunderstanding ofsuchdifferences, gainedthroughtheidentificationandcomparisonofscale books,canhelp eachviolinist andteacherapproacheachscale bookmoreintelligently.Thisdocumentoffershistorical andpracticalinformationforsome ofthemorewidelyused basicscalestudiesinviolin playing. Pedagogicalmaterialsforviolin,respondingtothetechnicaldemands andmusical trendsoftheinstrument , haveincreasedinnumber.Amongthem,Iwillexamineand comparethe contributionstothescale -

ORGAN ESSENTIALS Manual Technique Sheri Peterson [email protected]

ORGAN ESSENTIALS Manual Technique Sheri Peterson [email protected] Piano vs. Organ Tone “…..the vibrating string of the piano is loudest immediately after the attack. The tone quickly decays, or softens, until the key is released or until the vibrations are so small that no tone is audible.” For the organ, “the volume of the tone is constant as long as the key is held down; just prior to the release it is no softer than at the beginning.” Thus, the result is that “due to the continuous strength of the organ tone, the timing of the release is just as important as the attack.” (Don Cook: Organ Tutor, 2008, Intro 9 Suppl.) Basic Manual Technique • Hand Posture - Curve the fingers. Keep the hand and wrist relaxed. There is no need to apply excessive pressure to the keys. • Attack and Release - Precise rhythmic attack and release are crucial. The release is just as important as the attack. • Legato – Essential to effective hymn playing. • Independence – Finger and line. Important Listening Skills • Perfect Legato – One finger should keep a key depressed until the moment a new tone begins. Listen for a perfectly smooth connection. • Precise Releases – Listen for the timing of the release. Practice on a “silent” (no stops pulled) manual, listening for the clicks of the attacks and releases. • Independence of Line – When playing lines (voices) together, listen for a single line to sound the same as it does when played alone. (Don Cook: Organ Tutor, 2008, Intro 10 Suppl.) Fingering Technique The goal of fingering is to provide for the most efficient motion as possible. -

The Implications of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study*

Performance Practice Review Volume 5 Article 2 Number 2 Fall The mplicI ations of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study Desmond Hunter Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Hunter, Desmond (1992) "The mpI lications of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 5: No. 2, Article 2. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199205.02.02 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol5/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Renaissance Keyboard Fingering The Implications of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study* Desmond Hunter The fingering of virginalist music has been discussed at length by various scholars.1 The topic has not been exhausted however; indeed, the views expressed and the conclusions drawn have all too frequently been based on limited evidence. I would like to offer some observations based on both a knowledge of the sources and the experience gained from applying the source fingerings in performances of the music. I propose to focus on two related aspects: the fingering of linear figuration and the fingering of graced notes. Our knowledge of English keyboard fingering is drawn from the information contained in virginalist sources. Fingerings scattered Revised version of a paper presented at the 25th Annual Conference of the Royal Musical Association in Cambridge University, April 1990. -

Interaktiv June 2006 Page 1 Interaktiv Noch Zusätzlich Einen 90-Minütigen Vortrag Über Das Deutsche Gesundheits- Wesen an Einem Der Anderen Konferenztage, Bei Dem U.A

Liebe GLD-Mitglieder! von Frieda Ruppaner-Lind, GLD Administrator ie Sie bereits durch mehrere Ankündigungen unserer Verbandsleitung Werfahren haben, wird mit Beginn des Jahres 2006 keine zusätzliche Gebühr für die Mitgliedschaft in den ATA-Divisions mehr erhoben. Jedes ATA-Mitglied kann außerdem einer beliebigen Anzahl von Divisions beitreten. Dies führt zu einer Vereinfachung für die Division Administrators, die sich jetzt nicht mehr mit separaten Budgets abgeben müssen und automa- tisch für jede ATA-Konferenz zwei Sprecher direkt einladen können. Dies hängt auch nicht mehr von der Größe der einzelnen Divisions ab und gibt somit den kleineren Divisions die Möglichkeit, ein besseres Programm zu bieten. Ein anderer positiver Effekt ist die Erhöhung der Mitgliederzahlen in allen Divisions. Im Vergleich zum Vorjahr verfügt die GLD jetzt über ca. 950 Mitglieder, was einer Steigerung von 350 Mitgliedern entspricht. Für die Mitgliedschaft in der GLD-Liste in Yahoo Groups ist nach wie vor die Mitgliedschaft in der Division Voraussetzung. Auch hier ist ein Anstieg der Mitgliederzahl auf 231 Mitglieder zu verzeichnen, was gegenüber dem Vorjahr allerdings geringfügig ist. Trotzdem ist die Liste wie immer sehr aktiv und ich freue mich über die vielen interessanten Beiträge. Bevor der Sommer mit den hierzulande recht heißen Temperaturen heran- naht, waren die GLD-Administratoren wie im letzten Jahr wieder an der Gestaltung des deutschen Programmteils der ATA-Konferenz in New Orleans beteiligt. Wir haben uns auch die Vorschläge notiert, die während der GLD- Jahresversammlung in Seattle von Mitgliedern gemacht wurden; einer der Vorschläge lautete, etwas zum Thema Medizin zu präsentieren. Diesen Wunsch werden wir erfüllen können: Im Rahmen eines dreistündigen interaktiv Seminars am Mittwoch wird Prof. -

![Arxiv:1904.10237V2 [Cs.LG] 1 Jan 2020 Mance, Which Is One of the Most Skilled Movements of Humans [9, 26]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0091/arxiv-1904-10237v2-cs-lg-1-jan-2020-mance-which-is-one-of-the-most-skilled-movements-of-humans-9-26-890091.webp)

Arxiv:1904.10237V2 [Cs.LG] 1 Jan 2020 Mance, Which Is One of the Most Skilled Movements of Humans [9, 26]

Statistical Learning and Estimation of Piano Fingering∗ Eita Nakamura1;2;y, Yasuyuki Saito3, and Kazuyoshi Yoshii1 1Graduate School of Informatics, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan 2The Hakubi Center for Advanced Research, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan 3Department of Information and Computer Engineering, National Institute of Technology, Kisarazu College, Chiba 292-0041, Japan Abstract Automatic estimation of piano fingering is important for understanding the com- putational process of music performance and applicable to performance assistance and education systems. While a natural way to formulate the quality of fingerings is to construct models of the constraints/costs of performance, it is generally difficult to find appropriate parameter values for these models. Here we study an alternative data-driven approach based on statistical modeling in which the appropriateness of a given fingering is described by probabilities. Specifically, we construct two types of hidden Markov models (HMMs) and their higher-order extensions. We also study deep neural network (DNN)-based methods for comparison. Using a newly released dataset of fingering annotations, we conduct systematic evaluations of these models as well as a representative constraint-based method. We find that the methods based on high-order HMMs outperform the other methods in terms of estimation accuracies. We also quantitatively study individual difference of fingering and propose evaluation measures that can be used with multiple ground truth data. We conclude that the HMM-based methods are currently state of the art and generate acceptable finger- ings in most parts and that they have certain limitations such as ignorance of phrase boundaries and interdependence of the two hands. -

Character Studies After Elias Canetti

Joseph Klein Character Studies after Elias Canetti for various solo instruments ( 1997-2018 ) About this Collection This collection of short works for solo instruments is based upon characters from Der Ohrenzeuge : Fünfzig Charaktere (Earwitness : Fifty Characters ), written in 1974 by the Bulgaria-born British-Austrian writer Elias Canetti (1905-1994). Canetti’s distinctive studies incorporate poetic imagery, singular insights, and unabashed wordplay to create fifty ironic paradigms of human behavior. Begun in 1997, the present collection was inspired by Canetti’s vividly surreal depictions of these characters; seventeen works have been completed in this series to date : • Der Hinterbringer (The Tattletale) for solo piccolo (2013) • Der Ohrenzeuge (The Earwitness) for solo bass flute (2001) • Der Wasserhehler (The Water-harborer) for solo ocarina (2000) • Der Tückenfänger (The Wile-catcher) for solo basset horn (2014) • Der Leidverweser (The Woe-administrator) for solo contrabassoon (1998) • Die Müde (The Tired Woman) for solo alto saxophone (2004) • Der Schönheitsmolch (The Beauty-newt) for solo bass saxophone (2008) • Die Königskünderin (The King Proclaimer) for solo trumpet (2006) • Die Sternklare (The Starry Woman) for solo percussion (2006) • Der Fehlredner (The Misspeaker) for solo cimbalom (2018) • Die Silbenreine (The Syllable-pure Woman) for solo glass harmonica (2000) • Der Saus und Braus (The Fun-runner) for solo piano (2017) • Der Gottprotz (The God-swanker) for solo organ (2014) • Der Demutsahne (The Humility-forebear) for solo guitar (2008) • Die Tischtuchtolle (The Tablecloth-lunatic) for solo violin (1997) • Die Schadhafte (The Defective) for solo violoncello (2015) • Der Leichenschleicher (The Corpse-Skulker) for solo contrabass (1997) These works may be programmed individually or in sets of two or more. -

Basic Music Course: Keyboard Course

B A S I C M U S I C C O U R S E KEYBOARD course B A S I C M U S I C C O U R S E KEYBOARD COURSE Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah © 1993 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Updated 2004 English approval: 4/03 CONTENTS Introduction to the Basic Music Course .....1 “In Humility, Our Savior”........................28 Hymns to Learn ......................................56 The Keyboard Course..................................2 “Jesus, the Very Thought of Thee”.........29 “How Gentle God’s Commands”............56 Purposes...................................................2 “Jesus, Once of Humble Birth”..............30 “Jesus, the Very Thought of Thee”.........57 Components .............................................2 “Abide with Me!”....................................31 “Jesus, Once of Humble Birth”..............58 Advice to Students ......................................3 Finding and Practicing the White Keys ......32 “God Loved Us, So He Sent His Son”....60 A Note of Encouragement...........................4 Finding Middle C.....................................32 Accidentals ................................................62 Finding and Practicing C and F...............34 Sharps ....................................................63 SECTION 1 ..................................................5 Finding and Practicing A and B...............35 Flats........................................................63 Getting Ready to Play the Piano -

NACH BACH (1750-1850) GERMAN GRADED ORGAN REPERTOIRE by Dr

NACH BACH (1750-1850) GERMAN GRADED ORGAN REPERTOIRE By Dr. Shelly Moorman-Stahlman [email protected]; copyright Feb. 2007 LEVEL ONE Bach, Carl Phillip Emmanuel Leichte Spielstücke für Klavier This collection is one of most accessible collections for young keyboardists at late elementary or early intermediate level Bach, Wilhelm Friedermann Leichte Spielstücke für Klavier Mozart, Leopold Notenbuch für Nannerl Includes instructional pieces by anonymous composers of the period as well as early pieces by Wolfgang Amadeus Merkel, Gustav Examples and Verses for finger substitution and repeated notes WL Schneider, Johann Christian Friderich Examples including finger substitution included in: WL Türk, Daniel Gottlob (1750-1813) Sixty Pieces for Aspiring Players, Book II Based on Türk’s instructional manual, 120 Handstücke für angehende Klavierspieler, Books I and II, published in 1792 and 1795 Three voice manual pieces (listed in order of difficulty) Bach, C.P.E. Prelude in E Minor TCO, I Kittel, Johann Christian TCO, I Prelude in A Major Vierling, Johann Gottfried OMM V Short Prelude in C Minor Litzau, Johannes Barend Short Prelude in E Minor OMM V Four Short Preludes OMM III 1 Töpfer, Johann Gottlob OB I Komm Gott, Schöpfer, Heiliger Geist (stepwise motion) Kittel, Johann Christian Prelude in A Major OMM IV Fischer, Michael Gotthardt LO III Piu Allegro (dotted rhythms and held voices) Four voice manual pieces Albrechtsberger, Johann Georg Prelude in G Minor OMM, I Gebhardi, Ludwig Ernst Prelude in D Minor OMM, I Korner, Gotthilf Wilhelm LO I -

Electronic Music 1 Unleveled, 901 2.5 Credits

Electronic Music 1 Unleveled, 901 2.5 credits This course is an introduction to music and music technology. Students will how to read music, develop keyboard skills, and learn the basics of music theory and composition. Students will use the latest music technology including using Finale, Mixcraft , and Auralia software, as well as web-based skill development. No previous musical experience is required to take the class. Course Objectives: Concept List Students will be able to…… 1. Use correct posture and hand position at the keyboard. 2. Identify the fingers by number. 3. Notate music on the staff using bass and treble clefs, grand staff and rhythmic notation 4. Name, find, and play all black and white keys on the keyboard through written work and performance at the keyboard. 5. Tap two-part rhythm patterns. 6. Aurally distinguish simple rhythm patterns. 7. Identify 4/4 and 3/4 time signatures and apply them through written work and performance at the keyboard. 8. Play melodies in middle C position, C position, G position and other white key positions. 9. Perform solo repertoire from Grand Staff notation. 10. Apply additional musical concepts (crescendo, diminuendo, common time, slurs, legato phrase) to performance at the keyboard. 11. Identify steps and skips on the staff and perform them on the keyboard. 12. Identify melodic and harmonic intervals within the octave on the staff and perform them on the keyboard. 13. Identify and notate enharmonic equivalents. 14. Identify Italian tempo marks (allegro, moderato, andante) and apply them to performance on the keyboard 15. Apply additional musical concepts (incomplete measure, tied notes) through written work and performance at the keyboard. -

Template: Main Text

Starting from the End: A Proposal of Curriculum Guidelines for Beginning Cellists by Rodrigo Pessoa de Almeida, B.M., M.M. A Doctoral Performance Project In MUSIC PERFORMANCE Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS Professor Jeffrey Lastrapes Chair of Committee Dr. Stacey Jocoy Dr. Peter Fischer Dr. Mark Morton Dr. Annie Chalex Boyle Dr. Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School December, 2020 Copyright 2020, Rodrigo Pessoa de Almeida Texas Tech University, Rodrigo Pessoa de Almeida, December 2020 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my cello Professor, Mr. Jeffrey Lastrapes who played a decisive role in my formation as an accomplished musician. I also wish to thank my previous cello teacher, Dr. David Schepps from my Master’s degree at the University of New Mexico, for his guidance and friendship. Thanks should also go to all members of my committee Dr. Anne Chalex Boyle, Dr. Mark Morton, Dr. Peter Fischer, and Stacey Jocoy for their valuable advice and contributions to this document. The completion of my dissertation would not been possible without the support of all these experienced Professors. Particularly helpful to me during this time was Dr. Morton who taught me not only the bass but the wisdom of his pedagogical perspectives. I would like to acknowledge the assistance of Alex Claman, from the Graduate Writing Center, who guided me over the review of most of my grammatical errors while editing this document. I cannot leave Texas Tech University without mentioning all the support and love of my wife, Cassia, and my three children Abel, Helena, and Bernardo who patiently waited for my rare free times to have some family fun time during my doctoral studies. -

Wit and Humor in ASL Keila Tooley Eastern Illinois University This Research Is a Product of the Graduate Program in English at Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1986 Wit and Humor in ASL Keila Tooley Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Tooley, Keila, "Wit and Humor in ASL" (1986). Masters Theses. 2678. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2678 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date Author I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because �--�� Date m WIT AND HUMOR IN ASL (TITLE) BY Keila Tooley THESIS -

Tuesday Morning, 6 May 2014 555 A/B, 8:15 A.M

TUESDAY MORNING, 6 MAY 2014 555 A/B, 8:15 A.M. TO 11:55 A.M. Session 2aAA Architectural Acoustics: Uncertainty in Describing Room Acoustics Properties I Lily M. Wang, Cochair Durham School of Architectural Eng. and Construction, Univ. of Nebraska-Lincoln, 1110 S. 67th St., Omaha, NE 68182-0816 Ingo B. Witew, Cochair Inst. of Techn. Acoust., RWTH Aachen Univ., Neustrasse 50, Aachen 52066, Germany Chair’s Introduction—8:15 Invited Papers 2a TUE. AM 8:20 2aAA1. Review of the role of uncertainties in room acoustics. Ralph T. Muehleisen (Decision and Information Sci., Argonne National Lab., 9700 S. Cass Ave., Bldg. 221, Lemont, IL 60439, [email protected]) While many aspects of room acoustics such as material characterization, acoustic propagation and room interaction, and perception have long been, and continue to be, active areas of room acoustics research, the study of uncertainty in room acoustics has been very limited. Uncertainty pervades the room acoustic problem: there is uncertainty in measurement and characterization of materials, uncer- tainty in the models used for propagation and room interaction, uncertainty in the measurement of sound within rooms, and uncertainty in perception. Only recently are the standard methods of uncertainty assessment being systematically employed within room acoustics. This paper explains the need for systematic study of uncertainty in room acoustic predictions and review some of the most recent research related to characterizing uncertainty in room acoustics. 8:40 2aAA2. Uncertainty and stochastic computations in outdoor sound propagation. D. Keith Wilson (CRREL, U.S. Army ERDC, 72 Lyme Rd., Hanover, NH 03755-1290, [email protected]) and Chirs L.