Historical Performance Practices in Organ Works Before 1750 in Liège

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music for the Christmas Season by Buxtehude and Friends Musicmusic for for the the Christmas Christmas Season Byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and Friends Friends

Music for the Christmas season by Buxtehude and friends MusicMusic for for the the Christmas Christmas season byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and friends friends Else Torp, soprano ET Kate Browton, soprano KB Kristin Mulders, mezzo-soprano KM Mark Chambers, countertenor MC Johan Linderoth, tenor JL Paul Bentley-Angell, tenor PB Jakob Bloch Jespersen, bass JB Steffen Bruun, bass SB Fredrik From, violin Jesenka Balic Zunic, violin Kanerva Juutilainen, viola Judith-Maria Blomsterberg, cello Mattias Frostenson, violone Jane Gower, bassoon Allan Rasmussen, organ Dacapo is supported by the Cover: Fresco from Elmelunde Church, Møn, Denmark. The Twelfth Night scene, painted by the Elmelunde Master around 1500. The Wise Men presenting gifts to the infant Jesus.. THE ANNUNCIATION & ADVENT THE NATIVITY Heinrich Scheidemann (c. 1595–1663) – Preambulum in F major ������������1:25 Dietrich Buxtehude – Das neugeborne Kindelein ������������������������������������6:24 organ solo (chamber organ) ET, MC, PB, JB | violins, viola, bassoon, violone and organ Christian Geist (c. 1640–1711) – Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern ������5:35 Franz Tunder (1614–1667) – Ein kleines Kindelein ��������������������������������������4:09 ET | violins, cello and organ KB | violins, viola, cello, violone and organ Johann Christoph Bach (1642–1703) – Merk auf, mein Herz. 10:07 Dietrich Buxtehude – In dulci jubilo ����������������������������������������������������������5:50 ET, MC, JL, JB (Coro I) ET, MC, JB | violins, cello and organ KB, KM, PB, SB (Coro II) | cello, bassoon, violone and organ Heinrich Scheidemann – Preambulum in D minor. .3:38 Dietrich Buxtehude (c. 1637-1707) – Nun komm der Heiden Heiland. .1:53 organ solo (chamber organ) organ solo (main organ) NEW YEAR, EPIPHANY & ANNUNCIATION THE SHEPHERDS Dietrich Buxtehude – Jesu dulcis memoria ����������������������������������������������8:27 Dietrich Buxtehude – Fürchtet euch nicht. -

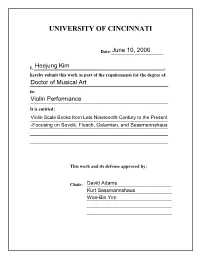

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ ViolinScaleBooks fromLateNineteenth-Centurytothe Present -FocusingonSevcik,Flesch,Galamian,andSassmannshaus Adocumentsubmittedtothe DivisionofGraduateStudiesandResearchofthe UniversityofCincinnati Inpartialfulfillmentoftherequirementsforthedegreeof DOCTORAL OFMUSICALARTS inViolinPerformance 2006 by HeejungKim B.M.,Seoul NationalUniversity,1995 M.M.,TheUniversityof Cincinnati,1999 Advisor:DavidAdams Readers:KurtSassmannshaus Won-BinYim ABSTRACT Violinists usuallystart practicesessionswithscale books,andtheyknowthe importanceofthem asatechnical grounding.However,performersandstudents generallyhavelittleinformation onhowscale bookshave beendevelopedandwhat detailsaredifferentamongmanyscale books.Anunderstanding ofsuchdifferences, gainedthroughtheidentificationandcomparisonofscale books,canhelp eachviolinist andteacherapproacheachscale bookmoreintelligently.Thisdocumentoffershistorical andpracticalinformationforsome ofthemorewidelyused basicscalestudiesinviolin playing. Pedagogicalmaterialsforviolin,respondingtothetechnicaldemands andmusical trendsoftheinstrument , haveincreasedinnumber.Amongthem,Iwillexamineand comparethe contributionstothescale -

Bengt Hambraeus' Livre D'orgue

ORGAN REGISTRATIONS IN BENGT HAMBRAEUS’ LIVRE D’ORGUE CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS AND REVISIONS Mark Christopher McDonald Organ and Church Music Area Department of Performance Schulich School of Music McGill University, Montreal, Quebec May 2017 A paper submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of D.Mus. Performance Studies. © 2017 Mark McDonald CONTENTS Index of Figures ......................................................................................................................... iv Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... vi Résumé ..................................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. viii I. Introduction – Opening a Time Capsule .................................................................................. 1 Bengt Hambraeus and the Notion of the “Time Capsule” .................................................... 2 Registration Indications in : Interpretive Challenges......................................... 3 Livre d’orgue Project Overview ................................................................................................................ 4 Methodology ..................................................................................................................... -

ORGAN ESSENTIALS Manual Technique Sheri Peterson [email protected]

ORGAN ESSENTIALS Manual Technique Sheri Peterson [email protected] Piano vs. Organ Tone “…..the vibrating string of the piano is loudest immediately after the attack. The tone quickly decays, or softens, until the key is released or until the vibrations are so small that no tone is audible.” For the organ, “the volume of the tone is constant as long as the key is held down; just prior to the release it is no softer than at the beginning.” Thus, the result is that “due to the continuous strength of the organ tone, the timing of the release is just as important as the attack.” (Don Cook: Organ Tutor, 2008, Intro 9 Suppl.) Basic Manual Technique • Hand Posture - Curve the fingers. Keep the hand and wrist relaxed. There is no need to apply excessive pressure to the keys. • Attack and Release - Precise rhythmic attack and release are crucial. The release is just as important as the attack. • Legato – Essential to effective hymn playing. • Independence – Finger and line. Important Listening Skills • Perfect Legato – One finger should keep a key depressed until the moment a new tone begins. Listen for a perfectly smooth connection. • Precise Releases – Listen for the timing of the release. Practice on a “silent” (no stops pulled) manual, listening for the clicks of the attacks and releases. • Independence of Line – When playing lines (voices) together, listen for a single line to sound the same as it does when played alone. (Don Cook: Organ Tutor, 2008, Intro 10 Suppl.) Fingering Technique The goal of fingering is to provide for the most efficient motion as possible. -

PIERRE COCHEREAU: a LEGACY of IMPROVISATION at NOTRE DAME DE PARIS By

PIERRE COCHEREAU: A LEGACY OF IMPROVISATION AT NOTRE DAME DE PARIS By ©2019 Matt Gender Submitted to the graduate degree program in School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ______________________________ Chairperson: Michael Bauer ______________________________ James Higdon ______________________________ Colin Roust ______________________________ David Alan Street ______________________________ Martin Bergee Date Defended: 05/15/19 The Dissertation Committee for Matt Gender certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: PIERRE COCHEREAU: A LEGACY OF IMPROVISATION AT NOTRE DAME DE PARIS _____________________________ Chairperson: Michael Bauer Date Approved: 05/15/19 ii ABSTRACT Pierre Cochereau (1924–84) was the organist of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris and an improviser of organ music in both concert and liturgical settings. He transformed the already established practices of improvising in the church into a modern artform. He was influenced by the teachers with whom he studied, including Marcel Dupré, Maurice Duruflé, and André Fleury. The legacy of modern organ improvisation that he established at Notre Dame in Paris, his synthesis of influences from significant figures in the French organ world, and his development of a personal and highly distinctive style make Cochereau’s recorded improvisations musically significant and worthy of transcription. The transcription of Cochereau’s recorded improvisations is a task that is seldom undertaken by organists or scholars. Thus, the published improvisations that have been transcribed are musically significant in their own way because of their relative scarcity in print and in concert performances. This project seeks to add to this published collection, giving organists another glimpse into the vast career of this colorful organist and composer. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19347-4 - Ritual Meanings in the Fifteenth-Century Motet Robert Nosow Excerpt More information Introduction As a dynamic force in the musical development of the fifteenth century, the motet has long been studied for the beauty of its polyphony and its prominent place in the manuscripts of the period. The genre has been associated with important churches, cathedrals, and princely courts across Western Europe. Motets rank among the most celebrated works of John Dunstaple, Guillaume Du Fay, Jacob Obrecht, and a host of other brilliant composers. Yet the motet also appears as a mysterious genre, both because of the multiplicity of forms it takes and because of the intractability of several related, unanswered questions. The investigation that follows addresses one central question: why did people write motets? In the last two decades, scholarly explications of individual motets have aimed to elucidate their potential significance for the late medieval period. Working from the texts and music outward has yielded new insights into the relationships between motets and fifteenth-century culture.1 Scholars inevitably have focused their attention on the few motets with overt cer- emonial associations, the Staatsmotetten. At the same time, the ability to ground interpretive or theoretical approaches in a concrete understanding of how motets were used in performance has proven elusive. Chroniclers of the fifteenth century, despite their keen interest in matters of ritual, did not consider it important enough to describe in detail the music at events of high state, or at imposing ecclesiastical ceremonies. They rarely mention the performance of motets, expressing more interest in the personages who 1 Among such studies for the first three quarters of the fifteenth century are J. -

Virtuosity and Technique in the Organ Works of Rolande Falcinelli

Virtuosity and Technique in the Organ Works of Rolande Falcinelli A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music by Loretta Graner BM, University of Kansas, 1984 MM, University of Kansas, 1988 April 2014 Committee Chair: Michael Unger, DMA ABSTRACT This study considers Rolande Falcinelli’s cultivation of technique and virtuosity as found in her organ methods and several of her organ works which have been evaluated from a pedagogical perspective. Her philosophical views on teaching, musical interpretation, and technique as expressed in three unpublished papers written by the composer are discussed; her organ methods, Initiation à l’orgue (1969–70) and École de la technique moderne de l’orgue (n.d.), are compared with Marcel Dupré’s Méthode d’orgue (pub. 1927). The unpublished papers are “Introduction à l’enseignement de l’orgue” (n.d.); “Regard sur l’interprétation à l’orgue,” (n.d.); and “Panorama de la technique de l’orgue: son enseignement—ses difficultés—son devenir” (n.d.). The organ works evaluated include Tryptique, Op. 11 (1941), Poèmes-Études (1948–1960), and Mathnavi, Op. 50 (1973). ii iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people have given generously of their time and resources to help me bring this document to fruition, and I am filled with gratitude when I reflect on their genuine, selfless kindness, their encouragement, and their unflagging support. In processions, the last person is the most highly honored, but I cannot rank my friends and colleagues in order of importance, because I needed every one of them. -

The Implications of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study*

Performance Practice Review Volume 5 Article 2 Number 2 Fall The mplicI ations of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study Desmond Hunter Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Hunter, Desmond (1992) "The mpI lications of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 5: No. 2, Article 2. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199205.02.02 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol5/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Renaissance Keyboard Fingering The Implications of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study* Desmond Hunter The fingering of virginalist music has been discussed at length by various scholars.1 The topic has not been exhausted however; indeed, the views expressed and the conclusions drawn have all too frequently been based on limited evidence. I would like to offer some observations based on both a knowledge of the sources and the experience gained from applying the source fingerings in performances of the music. I propose to focus on two related aspects: the fingering of linear figuration and the fingering of graced notes. Our knowledge of English keyboard fingering is drawn from the information contained in virginalist sources. Fingerings scattered Revised version of a paper presented at the 25th Annual Conference of the Royal Musical Association in Cambridge University, April 1990. -

The Baroque Offertoire : Apotheosis of the French Organ Art

The Baroque Offertoire : Apotheosis of the French Organ Art By Copyright 2016 Song Yi Park Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Michael Bauer ________________________________ Dr. James Higdon ________________________________ Dr. Colin Roust ________________________________ Dr. Bradley Osborn ________________________________ Professor Jerel Hildig Date Defended: November 1, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Song Yi Park certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Baroque Offertoire : Apotheosis of the French Organ Art ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Michael Bauer Date approved: November 1, 2016 ii Abstract During the French Baroque period, the function of the organ was primarily to serve the liturgy. It was an integral part of both Mass and the office of Vespers. Throughout these liturgies the organ functioned in alteration with vocal music, including Gregorian chant, choral repertoire, and fauxbourdon. The longest, most glorious organ music occurred at the time of the offertory of the Mass. The Offertoire was the place where French composers could develop musical ideas over a longer stretch of time and use the full resources of the French Classic Grand jeu , the most colorful registration on the French Baroque organ. This document will survey Offertoire movements by French Baroque composers. I will begin with an introductory discussion of the role of the offertory in the Mass and the alternatim plan in use during the French Baroque era. Following this I will look at the tonal resources of the French organ as they are incorporated into French Offertoire movements. -

The Influence of Plainchant on French Organ Music After the Revolution

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Doctoral Applied Arts 2013-8 The Influence of Plainchant on rF ench Organ Music after the Revolution David Connolly Technological University Dublin Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appadoc Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Connolly, D. (2013) The Influence of Plainchant on rF ench Organ Music after the Revolution. Doctoral Thesis. Dublin, Technological University Dublin. doi:10.21427/D76S34 This Theses, Ph.D is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License The Influence of Plainchant on French Organ Music after the Revolution David Connolly, BA, MA, HDip.Ed Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama Supervisor: Dr David Mooney Conservatory of Music and Drama August 2013 i I certify that this thesis which I now submit for examination for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in Music, is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others, save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. This thesis was prepared according to the regulations for postgraduate study by research of the Dublin Institute of Technology and has not been submitted in whole or in part for another award in any other third level institution. -

Basic Organ Registration by Margot Ann Woolard

Basic Organ Registration By Margot Ann Woolard Example 1 Introduction and Pitches Great: Spitzprincipal 8’ Swell: Rohrflöte 16’ & Great: Praestant 4’ Swell: Nazard 2-2/3’ & Swell: Blockflöte 2′ Swell: Tierce 1 – 3/5’ & Positiv: Larigot 1–1/3’ Positiv: Sifflöte 1′ Example 2 Principal (Diapason) Chord Progression and Scale Great: Spitzprincipal 8’ Praestant 4’ Spitzprincipal 8’ & Praestant 4’ Example 3 Flutes (open and stopped) Chord Progression and Scale Open Flute - Choir: Hohlflöte 8’ Stopped Flute – Swell: Rohrflöte 8’ Example 4 String Stops Chord Progression and Scale Swell: Viole de Gambe 8’ Example 5 Reed Stops Chord Progression and Scale Solo Reed – Choir: Cromorne 8’ Chorus Reed – Swell: Trompette 8’ Example 6 Principal Chorus Prelude in C Major (Eight Preludes and Fugues), J.S. Bach Great: Spitzprincipal 8’, Praestant 4’, Octave 2’ Pedal: Principal 16’, Octave 8’, Choral Bass 4’ Example 7 Stopped Flutes Number Six (Seven Pieces in E flat Major and E flat Minor, L’Organiste) Franck 1. Great : Bourdon 8’ 2. Swell: Viole de Gambe 8’ 3. Great: Bourdon 8’ Swell: Viole de Gambe 8’, Swell to Great coupler Example 8 Open Flutes Minuet (Musical Clocks), Haydn Positiv: Nachthorn 4’ Allein Gott in der höh sei Her, Zachau 1 Open Flute Chorus – Choir: Hohlflöte 8’, Positiv: Nachthorn 4’ Swell: Blockflöte 2’ Swell to Choir coupler Example 9 String Stops All Glory be to God on High (79 Chorales), Marcel Dupré Swell: Viole de Gambe 8’ (accompaniment) Great: Bourdon 8’ (melody) Pedal : Rohrflöte 16’. Rohrflöte 8’ (bass) Example 10 Voix Celeste -

A Central European Composer

De musica disserenda II/1 • 2006 • 103–112 PETRUS WILHELMI DE GRUDENcz (b. 1392) – A CENTRAL EUROPEAN COMPOSER Paweł Gancarczyk Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw Abstract: According to present knowledge, Petrus Izvleček: Po sedanjem vedenju sestoji opus Petrusa Wilhelmi’s output numbers about 40 compositions Wilhelmi iz ok. 40 kompozicij, ohranjenih v pri- preserved in about 45 sources. Apart from Latin bližno 45 virih. Poleg latinskih pesmi (cantiones) songs (cantiones) he composed polytextual motets je komponiral politekstualne motete in kanone and canons (rotula). Petrus Wilhelmi was active (rotula). Petrus Wilhelmi je deloval skoraj izključno almost exclusively on the ground of Central Europe le v srednji Evropi in predstavlja najizrazitejšega and must be regarded as the most prominent Central srednjeevropskega skladatelja 15. stol. European composer of the 15th century. Keywords: 15th-century polyphony, polytextual motet, Ključne besede: polifonija 15. stol., politekstualni cantio, music in Central Europe motet, cantio, glasba v srednji Evropi Thirty years ago, in 1975, the Czech musicologist Jaromír Černý announced the discovery of a new composer – Petrus Wilhelmi de Grudencz. The discovery was based on research into the Bohemian repertory of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century polyphonic music. Černý distinguished in it a group of stylistically related compositions, the texts of which contained the acrostic “Petrus”. However, the key part in the discovery of the previously unknown composer was played by the motet Pneuma eucaristiarum / Veni vere / Dator eya / Paraclito tripudia. This was a work composed for four voices, each voice with a different text. One of the texts contained the acrostic “Petrus”, the remaining two the acrostics “Wilhelmi” and “de Grudencz”.