PIERRE COCHEREAU: a LEGACY of IMPROVISATION at NOTRE DAME DE PARIS By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Welcome to Shadyside Presbyterian Church

Welcome to Shadyside Presbyterian Church We are grateful for your presence and invite you to participate in the worship, study, fellowship, and service of this congregation. If you are a guest with us this morning, our ushers are available to assist you. Following worship, we invite those who are new to the church to join us under the ficus tree in the Sharp Atrium, where New Member Committee representatives will greet you and answer any questions you may have. Nursery care is available for infants through three-year-olds during worship. Pagers are available. A cry room with an audio broadcast of worship is available downstairs in the Marks Room. Children in Worship – At 11:00 a.m., families with two- and three-year-olds are welcome to report directly to the Nursery. Four-year-olds through second-graders attend worship and may exit with their teachers before the sermon to participate in children’s chapel worship and Christian education. (If you are a first-time guest, please accompany your child to the Chapel, and then you may return to the Sanctuary.) Parents should meet their children in the Christian education classrooms after worship. On the first Sunday of the month, first- and second-graders stay in worship through the entire service for Communion. A bulletin insert designed for children is available in the Narthex. A video broadcast of worship is available in the Craig Room, accessible through the Narthex at the back of the Sanctuary. Flower Ministry – After worship, members of the Board of Deacons’ Flower Ministry divide the chancel flowers into bouquets to be distributed to individuals who are celebrating joyous occasions and to those who could use some cheer. -

PIPEDREAMS Programs, May 2021 Spring Quarter

PIPEDREAMS Programs, May 2021 Spring Quarter: The following listings detail complete contents for the May 2021 Spring Quarter PIPEDREAMS broadcasts. The first section includes complete program contents, with repertoire, artist, and recording information. Following that is program information in "short form". For more information, contact your American Public Media station relations representative at 651-290-1225/877- 276-8400 or the PIPEDREAMS Office (651-290-1539), Michael Barone <[email protected]>). For last-minute program changes, watch DACS feeds from APM and check listing details on our PIPEDREAMS website: http://www.pipedreams.org AN IMPORTANT NOTE: It would be prudent to keep a copy of this material on hand, so that you, at the local station level, can field listener queries concerning details of individual program contents. That also keeps YOU in contact with your listeners, and minimizes the traffic at my end. However, whenever in doubt, forward calls to me (Barone). * * * * * * * PIPEDREAMS Program No. 2118 – May Flowers (distribution on 5/3/2021) Maytime Flowers . in hopes that April showers have done their work, we offer up this melodious musical bouquet. [Hour 1] AARON DAVID MILLER: A Flower Opens –Aaron David Miller (1979 Fisk/House of Hope Presbyterian Church, Saint Paul, MN) Pipedreams Archive (r. 3/18/12) SIR FREDERICK BRIDGE: Flowers of the Forest –Simon Nieminski (1913 Brindley & Foster/Freemasons Hall, Edinburgh) Pro Organo 7240) LEONARD DANEK: Flowers –Leonard Danek (1979 Sipe/Hennepin Avenue United Methodist Church, -

CHURCH ORGANIST Job Description Principal Function the Church Organist Is a Committed Christian Who Provides Organ Music And

CHURCH ORGANIST Job Description Principal Function The Church Organist is a committed Christian who provides organ music and accompaniment for scheduled worship services and other activities in support of the music ministry of the church. Having a pivotal role in the musical life of the church, this individual is a strong team player, being a full partner with the ministerial staff and the Church Pianist of Shades Crest Baptist Church. Job Description This year-round position is defined as salary (no overtime pay), restricted part time. Expectation of attendance is for Sunday worship services, rehearsals with the Sanctuary Choir and the Orchestra, and other special services, including (but not limited to) Christmas and Easter. The work is done cooperatively, especially with the Music Minister and the Church Pianist. As a part of the musical leadership team of the church, the Organist is expected to advocate for the music program. Job Requirements 1. A disciple of Jesus Christ, committed to growing in faith through practicing the spiritual disciplines of prayer, Scripture study, worship participation, and service at and beyond Shades Crest Baptist Church. 2. Experience in church worship, with both organ and other music and hymnody (understanding and familiarity with blended worship preferred). 3. Flexibility to play in blended style services that include all types of worship music. 4. Knowledge of the instrument and keyboard ability sufficient to play hymns, songs, and anthem accompaniments. Ability to sight-read and improvise is desired. 5. High degree of competence on organ, and the ability to accompany groups and individuals. 6. Knowledge of basic music theory and ability to perform simple transpositions or harmonizations. -

The Chapel Organ

Pedal Organ Couplers 23 stops, 11 ranks (Pulpit and Lectern Great to Great 16/4 Positiv Unison Off THE CHAPEL ORGAN sides, partly exposed and enclosed) Great Unison Of Great to Positiv Resultant 32 derived Swell to Great 16/8/4 Swell to Positiv 16/8/4 Principal 16 32 pipes F Choir to Great 16/8/4 Choir to Positiv 16/8/4 Brummbass 16 32 pipes* Positiv to Great 16/8 Rohrflöte 16 (Swell) Swell to Swell 16/4 Violone 16 (Great) Swell Unison Off Octave 8 32 pipes A Choir to Choir 16/4 Great Organ Positiv Organ Choir Unison Off Great to Pedal Bordun 8 12 pipes* 12 stops, 15 ranks (Pulpit side, 11 stops, 14 ranks (Lectern side, Great to Choir Swell to Pedal 8/4 Rohrflöte 8 (Swell) partly exposed on wall, unenclosed) partly exposed on wall, unenclosed) Swell to Choir Choir to Pedal 8/4 Violone 8 (Great) Violone 16 61 pipes F Holzflöte 8 61 pipes B Positiv to Choir Positiv to Pedal Choralbass 4 32 pipes Principal 8 61 pipes A Octave 4 61 pipes A Flöte 4 12 pipes Bordun 8 61 pipes B Koppelflöte 4 61 pipes B Accessories Octavin 2 (from Mix II) Violone 8 12 pipes Super Octave 2 61 pipes A 256 Memory Levels Mixture II 2 2/3 64 pipes* Octave 4 61 pipes A Waldflöte 2 61 pipes B (12 Generals and 8 Divisionals) Mixture IV 1 1/3 128 pipes Hohlflöte 4 61 pipes B Quinte 1 1/3 61 pipes A 2 Tuttis Kontra Posaune 32 12 pipes Fifteenth 2 61 pipes A Sesquialtera II 2 2/3 122 pipes B Crescendo with Indicator Posaune 16 32 pipes Cornet III 2 2/3 183 pipes B Scharf IV 1 244 pipes A Nave Shades Off Basson-Hautbois 16 (Swell) Mixture V 2 305 pipes A Dulcian 16 12 pipes -

Ofmusic PROGRAM

GUEST ARTIST RECITAL OLIVIER LATRY, Organ Tuesday, February 21, 2012 7:00 p.m. Edythe Bates Old Recital Hall and Grand Organ ~herd RICE UNIVERSITY Sc~ol ofMusic PROGRAM Cortege et litanie Marcel Dupre (1886-1971) ,._ Petite Rapsodie improvisee Charles Tournemire (1870-1939) L'Ascension Olivier Messiaen Majeste du Christ demandant sa gloire a son Pere (1908-1992) Alleluias sereins d 'une ame qui desire le ciel Transports de Joie d 'une ame Priere du Christ montant vers son Pere INTERMISSION Trois danses JehanAlain Joies (1911-1940) Deuils Luttes Improvisation Olivier Latry Olivier Latry is represented by Karen McFarlane Artists, Inc. .. The reverberative acoustics of Edythe Bates Old Recital Hall magnify the slightest sound made by the audience. Your care and courtesy will be appreciated. The taking ofphotographs and use of recording equipment are prohibited. BIOGRAPHY Olivier Latry, titular organist of the Cathedral ofNotre-Dame in Paris, is one of the world's most distinguished organists. He was born in 1962 in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France, and began his study ofpiano at age 7 and his study of the organ at age 12; he later attended the Academy ofMusic at St. Maur-des-Fosses, studying organ with Gaston Litaize. From 1981 until 1985 Olivier Latry was titular organist ofMeaux Cathedral, and at age 23 he won a competition to become one of the three titular organists of the Ca thedral ofNotre-Dame in Paris. From 1990 until 1995 he taught organ at the Academy ofMusic at St. Maur-des-Fosses, where he succeeded his teacher, Gaston Litaize. Since 1995 he has taught at the Paris Conservatory, where he has succeeded Michel Chapuis. -

Bengt Hambraeus' Livre D'orgue

ORGAN REGISTRATIONS IN BENGT HAMBRAEUS’ LIVRE D’ORGUE CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS AND REVISIONS Mark Christopher McDonald Organ and Church Music Area Department of Performance Schulich School of Music McGill University, Montreal, Quebec May 2017 A paper submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of D.Mus. Performance Studies. © 2017 Mark McDonald CONTENTS Index of Figures ......................................................................................................................... iv Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... vi Résumé ..................................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. viii I. Introduction – Opening a Time Capsule .................................................................................. 1 Bengt Hambraeus and the Notion of the “Time Capsule” .................................................... 2 Registration Indications in : Interpretive Challenges......................................... 3 Livre d’orgue Project Overview ................................................................................................................ 4 Methodology ..................................................................................................................... -

The Baroque Offertoire : Apotheosis of the French Organ Art

The Baroque Offertoire : Apotheosis of the French Organ Art By Copyright 2016 Song Yi Park Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Michael Bauer ________________________________ Dr. James Higdon ________________________________ Dr. Colin Roust ________________________________ Dr. Bradley Osborn ________________________________ Professor Jerel Hildig Date Defended: November 1, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Song Yi Park certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Baroque Offertoire : Apotheosis of the French Organ Art ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Michael Bauer Date approved: November 1, 2016 ii Abstract During the French Baroque period, the function of the organ was primarily to serve the liturgy. It was an integral part of both Mass and the office of Vespers. Throughout these liturgies the organ functioned in alteration with vocal music, including Gregorian chant, choral repertoire, and fauxbourdon. The longest, most glorious organ music occurred at the time of the offertory of the Mass. The Offertoire was the place where French composers could develop musical ideas over a longer stretch of time and use the full resources of the French Classic Grand jeu , the most colorful registration on the French Baroque organ. This document will survey Offertoire movements by French Baroque composers. I will begin with an introductory discussion of the role of the offertory in the Mass and the alternatim plan in use during the French Baroque era. Following this I will look at the tonal resources of the French organ as they are incorporated into French Offertoire movements. -

EN CHAMADE U the Newsletter of the Winchester American Guild of Organists

u EN CHAMADE u The Newsletter of the Winchester American Guild of Organists Daniel Hannemann, editor [email protected] Our website: http://www.agohq.org/chapters/winchester June ~ July ~ August 2016 From the Dean - - - The recital series proposed by the board for the Lutheran retirement community at Orchard Ridge was enthusiastically accepted by administrators at Orchard Ridge. Judy Connelly, Daniel Hannemann, & Steven Cooksey met with officials from the village in late March. Below are excerpts from the minutes taken by the Director of Activities at Orchard Ridge. Hopefully, they provide a clear picture of our series. Examination of the instrument has shown it to be first rate and quite versatile. Guild members are encouraged to come and practice on it, provided the room is free (it is best to call ahead). A receptionist has a list of our members and will direct you to the chapel. Steven Cooksey, in consultation with several of the members, has arranged for the first seven concerts. Each will be shared by two or more musicians, with occasional orchestral instruments or piano. If you are willing/interested in playing on future programs, but are not scheduled for any of the first seven, please contact Dr. Cooksey. We are interested in having a large number of our members perform. - Minutes from WAGO/Orchard Ridge Meeting - Concerts are scheduled for the second Monday monthly beginning with Monday, June 13; concerts will begin at 7 p.m. • Concerts are scheduled through December 2016, with a review to determine continued coordination for additional months/second part in 2017. • Concerts will be theme-based with either a single performer or multiple performers. -

The Tuesday Concert Series at Tuesday Maintain Epiphany’S Artistic Profile the Church of the Epiphany and Its Instruments

the HOW YOU CAN CONSIDER HELPING THE TUESDAY CONCERT SERIES AT TUESDAY MAINTAIN EPIPHANY’S ARTISTIC PROFILE THE CHURCH OF THE EPIPHANY AND ITS INSTRUMENTS CONCERT The Tuesday Concert Series reaches out to the entire metropolitan Washington community 52 weeks of the year, and Since the Church of the Epiphany was founded in brings both national and international artists here to 1842, music has played a vital role in the life of the parish. The Tuesday Concert Series reaches out to the SERIES Washington, DC. The series enjoys partnerships with many entire metropolitan Washington community and runs artistic groups in the area, too, most keenly with the Washington throughout the year. No other concert series follows July - December Bach Consort, the Levine School of Music, and the Avanti such a pattern and, as such, it is unique in the 2017 Orchestra. Washington, DC area. There is no admission charge to the concerts, and visitors and Epiphany houses three fine musical instruments: The regular concert-goers are invited to make a freewill offering to Steinway D concert grand piano was a gift to the support our artists. This freewill offering has been the primary church in 1984, in memory of vestry member Paul source of revenue from which our performers have been Shinkman, and the 4-manual, 64-rank, 3,467-pipe remunerated, and a small portion of this helps to defray costs of Æolian-Skinner pipe organ (1968) is one of the most the church’s administration, advertising and instrument upkeep. versatile in the city. The 3-stop chamber organ (2014), Today, maintaining the artistic quality of Epiphany’s series with commissioned in memory of Albert and Frances this source of revenue is challenging. -

The Influence of Plainchant on French Organ Music After the Revolution

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Doctoral Applied Arts 2013-8 The Influence of Plainchant on rF ench Organ Music after the Revolution David Connolly Technological University Dublin Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appadoc Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Connolly, D. (2013) The Influence of Plainchant on rF ench Organ Music after the Revolution. Doctoral Thesis. Dublin, Technological University Dublin. doi:10.21427/D76S34 This Theses, Ph.D is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License The Influence of Plainchant on French Organ Music after the Revolution David Connolly, BA, MA, HDip.Ed Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama Supervisor: Dr David Mooney Conservatory of Music and Drama August 2013 i I certify that this thesis which I now submit for examination for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in Music, is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others, save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. This thesis was prepared according to the regulations for postgraduate study by research of the Dublin Institute of Technology and has not been submitted in whole or in part for another award in any other third level institution. -

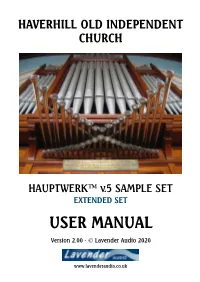

User Manual Available Either Online Or on the Installation Media to Familiarise Yourself with the Various Features It Offers

HAUPTWERK™ v.5 SAMPLE SET Version 2.00 - © Lavender Audio 2020 www.lavenderaudio.co.uk Thank you for purchasing this sample set. Please note that installation files for the Haverhill OIC set are available either for download or can be supplied on a USB Memory Stick at a modest additional cost. It is recommended that you take a little time to read the user manual available either online or on the installation media to familiarise yourself with the various features it offers. Installation of the Haverhill OIC Full set The Full sample set requires a total of two Data packages and one Organ package to be installed. These are identified as follows … Haverhill-DataPackage-674 Haverhill-DataPackage-675 Haverhill-Full-OrganPackage For correct installation, it is essential that Hauptwerk’s component installer is used. Start Hauptwerk and (unless installing from a download) insert the USB memory stick into a suitable USB port. In Hauptwerk, choose “File | Install organ, temper- ament or impulse response reverb...” and then navigate to the USB drive or to the location you saved the downloaded instal- lation files and find the first data installation package (674). Once Hauptwerk has analysed the package you may be presented with the sample set licence which you will need to accept. After a while, the following screen is presented: Ensure that the Selected installation action for the [Data] item is set to Install and then click OK. Installation should then proceed and the whole process should complete quickly. Repeat this process for DataPackage-675. When it comes to installing the Haverhill-Full-OrganPackage, you will notice that two organs are available to be installed - these are as follows .. -

Rcco Toronto Centre Substitute Organist List

RCCO TORONTO CENTRE SUBSTITUTE ORGANIST LIST Included in this list is the contact information for organists in the Greater Toronto Area who are available as substitutes. Several of the organists on this list have provided a short biography detailing their experience, which you can read on the following pages of this document. If you would like to be added or removed from this list, please email Sebastian Moreno at [email protected]. You must be a current Toronto Centre RCCO member to appear on the list! Name Phone E-mail Location Peter Bayer (703) 209-5892 [email protected] Toronto Paulo Busato (416) 795-8877 [email protected] Toronto John Charles (289) 788-6451 [email protected] Toronto/ Hamilton J.-C. Coolen (905) 683-5757 [email protected] Ajax Patrick Dewell (647) 657-2486 [email protected] Toronto Quirino Di Giulio (416) 323-1537 [email protected] Toronto Kelly Galbraith (416) 655-7335 [email protected] Toronto Marianne Gast (416) 944-9698 [email protected] Toronto William Goodfellow (416) 694-3753 [email protected] Scarborough Kimberly Hanmer (416) 417-1325 [email protected] Toronto/ Hamilton Christine Hanson (647) 460-7027 [email protected] Toronto Paul Jessen (416) 419-6904 [email protected] Toronto Glenn Keefe [email protected] Toronto Matthew Larkin [email protected] Toronto/ Ottawa Sebastian Moreno (647) 278-5559 [email protected] Mississauga/ Toronto Gerald Martindale (647) 458-0213 [email protected]