Influence, Intrigue and Individuals Wheatley Westgate 1560-1640

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Original Lists of Persons of Quality, Emigrants, Religious Exiles, Political

Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924096785278 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1992 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 2003 H^^r-h- CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE : ; rigmal ^ist0 OF PERSONS OF QUALITY; EMIGRANTS ; RELIGIOUS EXILES ; POLITICAL REBELS SERVING MEN SOLD FOR A TERM OF YEARS ; APPRENTICES CHILDREN STOLEN; MAIDENS PRESSED; AND OTHERS WHO WENT FROM GREAT BRITAIN TO THE AMERICAN PLANTATIONS 1600- I 700. WITH THEIR AGES, THE LOCALITIES WHERE THEY FORMERLY LIVED IN THE MOTHER COUNTRY, THE NAMES OF THE SHIPS IN WHICH THEY EMBARKED, AND OTHER INTERESTING PARTICULARS. FROM MSS. PRESERVED IN THE STATE PAPER DEPARTMENT OF HER MAJESTY'S PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE, ENGLAND. EDITED BY JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. L n D n CHATTO AND WINDUS, PUBLISHERS. 1874, THE ORIGINAL LISTS. 1o ihi ^zmhcxs of the GENEALOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETIES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THIS COLLECTION OF THE NAMES OF THE EMIGRANT ANCESTORS OF MANY THOUSANDS OF AMERICAN FAMILIES, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED PY THE EDITOR, JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. CONTENTS. Register of the Names of all the Passengers from London during One Whole Year, ending Christmas, 1635 33, HS 1 the Ship Bonavatture via CONTENTS. In the Ship Defence.. E. Bostocke, Master 89, 91, 98, 99, 100, loi, 105, lo6 Blessing . -

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

A Short History of WHEATLEY STONE

A Short History of WHEATLEY STONE By W. O. HASSALL ILLUSTRATED BY PETER TYSOE 1955 Printed at the Oxford School of Art WHEATLEY STONE The earliest quarry at Wheatley to be named in the records is called Chalgrove, but it is not to be confused with the famous field of the same name where John Hampden was mortally wounded and which was transformed into an aerodrome during the war. Chalgrove in Wheatley lies on the edge of Wheatley West field, near the boundary of Shotover Park on the south side of the road from London to High Wycombe, opposite a turning to Forest Hill and Islip where a modern quarry is worked for lime, six miles East of Oxford. The name of Challrove in Wheatley is almost forgotten, except by the elderly, though the name appears in the Rate books. The exact position is marked in a map of 1593 at All Souls College and grass covered depressions which mark the site are visible from the passing buses. The All Souls map shows that some of these depressions, a little further east, were called in Queen Elizabeth’s reign Glovers and Cleves pits. The Queen would have passed near them when she travelled as a prisoner from Woodstock to Rycot on a stormy day when the wind was so rough that her captors had to hold down her dress and later when she came in triumph to be welcomed by the City and University at Shotover, on her way to Oxford. The name Chaigrove is so old that under the spelling Ceorla graf it occurs in a charter from King Edwy dated A.D. -

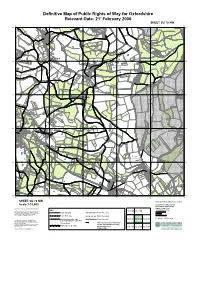

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21St February 2006 Colour SHEET SU 78 NW

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21st February 2006 Colour SHEET SU 78 NW 70 71 72 73 74 75 B 480 1200 7900 B 480 8200 0005 Highclere B 480 7300 The Well The B 480 Croft Crown Inn The Old School House Unity Cottage 322/25 90 Pishilbury 90 377/30 Cottage Hall 322/21 Well 322/20 Pool Walnut Tree Cottage 3 THE OLD ROAD 2/2 32 Bank Farm Walnut Tree Cottage 8086 CHURCH HILL The Beehive Balhams' Farmhouse Pishill Church 9683 LANE 2/22 6284 Well Pond Hall Kiln BALHAM'S Barn 32 PISHILL Kiln Pond 322/22 6579 Cottages 0076 322/22 HOLLANDRIDGE LANE Upper Nuttalls Farm 322/16 Chapel Wells Pond 0076 Thatchers Pishill House 0974 322/15 5273 Green Patch 322/25 Rose Cottage Pond B 480 The Orchard B 480 7767 Horseshoe Cottage Strathmore The 322/17 37 Old Chapel Lincolns Thatch Cottage Ramblers Hey The White House 7/ Goddards Cottage 322/22 The Old Farm House 30 April Cottage The Cottage Softs Corner Tithe Barn Law Lane 377/30 Whitfield Flint Cottage Commonside Cedarcroft BALHAM'S LANE 322/20 322/ Brackenhurst Beech Barn 0054 0054 27 322/23 6751 Well 322/10 Whistling Cottage 0048 5046 Morigay Nuttall's Farm Tower Marymead Russell's Water 2839 Farm 377/14 Whitepond Farm 322/9 0003 377/15 7534 0034 Pond 0034 Redpitts Lane Little Balhams Pond Elm Tree Hollow Snowball Hill 1429 Ponds Stonor House Well and remains of 0024 3823 Pond 2420 Drain RC Chapel Pond (Private) 5718 Pond Pond Pond 322/20 Redpitts Farm 9017 0513 Pond Pavilion Lodge Lodge 0034 The Bungalow 1706 0305 9 4505 Periwinkle 7/1 Cottage 0006 Well 322/10 0003 -

George Edmund Street

DOES YOUR CHURCH HAVE WORK BY ONE OF THE GREATEST VICTORIAN ARCHITECTS? George Edmund Street Diocesan Church Building Society, and moved to Wantage. The job involved checking designs submitted by other architects, and brought him commissions of his own. Also in 1850 he made his first visit to the Continent, touring Northern France. He later published important books on Gothic architecture in Italy and Spain. The Diocese of Oxford is extraordinarily fortunate to possess so much of his work In 1852 he moved to Oxford. Important commissions included Cuddesdon College, in 1853, and All Saints, Boyne Hill, Maidenhead, in 1854. In the next year Street moved to London, but he continued to check designs for the Oxford Diocesan Building Society, and to do extensive work in the Diocese, until his death in 1881. In Berkshire alone he worked on 34 churches, his contribution ranging from minor repairs to complete new buildings, and he built fifteen schools, eight parsonages, and one convent. The figures for Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire are similar. Street’s new churches are generally admired. They include both grand town churches, like All Saints, Boyne Hill, and SS Philip and James, Oxford (no longer in use for worship), and remarkable country churches such as Fawley and Brightwalton in Berkshire, Filkins and Milton- under-Wychwood in Oxfordshire, and Westcott and New Bradwell in Buckinghamshire. There are still some people for whom Victorian church restoration is a matter for disapproval. Whatever one may think about Street’s treatment of post-medieval work, his handling of medieval churches was informed by both scholarship and taste, and it is George Edmund Street (1824–81) Above All Saints, Boyne His connection with the Diocese a substantial asset for any church to was beyond doubt one of the Hill, Maidenhead, originated in his being recommended have been restored by him. -

40 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

40 bus time schedule & line map 40 High Wycombe View In Website Mode The 40 bus line (High Wycombe) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) High Wycombe: 6:30 AM - 8:35 PM (2) Thame: 6:15 AM - 8:35 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 40 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 40 bus arriving. Direction: High Wycombe 40 bus Time Schedule 46 stops High Wycombe Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 8:45 AM - 6:35 PM Monday 6:30 AM - 8:35 PM Town Hall, Thame 1 High Street, Thame Tuesday 6:30 AM - 8:35 PM Health Centre, Thame Wednesday 6:30 AM - 8:35 PM Orchard Close, Thame Thursday 6:30 AM - 8:35 PM Churchill Crescent, Thame Friday 6:30 AM - 8:35 PM Windmill Road, Towersey Saturday 7:38 AM - 8:35 PM Thame Road, Towersey Civil Parish Village Hall, Towersey Waterlands Farm, Emmington 40 bus Info Direction: High Wycombe The Inn at Emmington, Sydenham Stops: 46 Thame Road, Chinnor Civil Parish Trip Duration: 54 min Line Summary: Town Hall, Thame, Health Centre, Thame Road Shops, Chinnor Thame, Churchill Crescent, Thame, Windmill Road, Towersey, Village Hall, Towersey, Waterlands Farm, Springƒeld Gardens, Chinnor Emmington, The Inn at Emmington, Sydenham, Lower Road, Chinnor Thame Road Shops, Chinnor, Springƒeld Gardens, Chinnor, The Red Lion, Chinnor, The Village Centre, The Red Lion, Chinnor Chinnor, Village Hall, Chinnor, Glynswood, Chinnor, Chiltern Hill Garage, Chinnor, Glimbers Green, The Village Centre, Chinnor Chinnor, St Marys Church, Crowell, The Cherry Tree, Kingston Blount, Village Turn, -

Vine Cottage Denton

Vine Cottage Denton Vine Cottage Denton, Oxfordshire Oxford 5 miles (trains to London Paddington), Haddenham and Thame Parkway 11 miles (trains to London Marylebone), Thame 10 miles, Abingdon 11 miles, Didcot 12 miles, London 55 miles (all times and di ances are approximate) A beautifully maintained period cottage with exquisite gardens in a quiet rural hamlet near Oxford. Hall | Drawing room | Kitchen/dining room | Study | Utility room | Cloakroom Four bedrooms | Two bath/shower rooms Deligh ul gardens | Raised beds | Pond | Vegetable garden | Green house | Summerhouse Potential to extend or convert the outbuildings into an annexe About 1 acre Knight Frank Oxford 274 Banbury Road Oxford, OX2 7DY 01865 264 879 harry.sheppard@knigh rank.com knigh rank.co.uk The Cottage Built in 1835, Vine Co age is a charming co age with much chara er set in an area of out anding natural beauty. The location of the property really is a naturi s, walkers and gardeners dream, in a rural position with panoramic views over open countryside. Whil feeling rural the property is conveniently close to the village of Cuddesdon which o ers a public house and a church and Oxford is only 5 miles away. Whil retaining many original chara er features the property has been sympathetically extended and has the advantage of not being li ed. Presented to an extremely high andard throughout. The majority of the roof was re-thatched in 2018, a new kitchen and shower room in alled in 2016 and the family bathroom was replaced in 2020. There is a high ecifi cation fi nish throughout the house including an integrated Sonos sy em and Boss eakers which complement the original chara er that has been beautifully re ored and maintained. -

Meeting with Warwickshire County Council

Summary of changes to subsidised services in the Wheatley, Thame & Watlington area Effective from SUNDAY 5th June 2011 ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... Line 40:- High Wycombe – Chinnor – Thame Broadly hourly service maintained, operated by Arriva the Shires. Only certain journeys will serve Towersey village, but Towersey will also be served by routes 120 and 123 (see below). Service 101:- Oxford – Garsington – Watlington A broadly hourly service maintained, operated by Thames Travel Monday to Saturday between Oxford City Centre and Garsington. Certain peak buses only will start from or continue to Chalgrove and Watlington, this section otherwise will be served by route 106 (see below). Service 101 will no longer serve Littlehay Road or Rymers Lane, or the Cowley Centre (Nelson) stops. Nearest stops will be at the Original Swan. Service 102:- Oxford – Horspath – Watlington This Friday and Saturday evening service to/from Oxford City is WITHDRAWN. Associated commercial evening journeys currently provided on route 101 by Thames Travel will also be discontinued. Service 103:- Oxford – Horspath – Wheatley – Great Milton - Little Milton Service 104:- Oxford – Horspath – Wheatley – Great Milton – Cuddesdon /Denton A broadly hourly service over the Oxford – Great Milton section will continue to be operated by Heyfordian Travel Mondays to Saturdays. Buses will then serve either Little Milton (via the Haseleys) or Cuddesdon / Denton alternately every two hours as now. The route followed by service 104 will be amended in the Great Milton area and the section of route from Denton to Garsington is discontinued. Routes 103 and 104 will continue to serve Littlehay Road and Rymers Lane and Cowley (Nelson) stops. Service 113 is withdrawn (see below). -

Timetables: South Oxfordshire Bus Services

Drayton St Leonard - Appleford - Abingdon 46 Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays Drayton St Leonard Memorial 10.00 Abingdon Stratton Way 12.55 Berinsfield Interchange west 10.05 Abingdon Bridge Street 12.56 Burcot Chequers 10.06 Culham The Glebe 13.01 Clifton Hampden Post Office 10.09 Appleford Carpenters Arms 13.06 Long Wittenham Plough 10.14 Long Wittenham Plough 13.15 Appleford Carpenters Arms 10.20 Clifton Hampden Post Office 13.20 Culham The Glebe 10.25 Burcot Chequers 13.23 Abingdon War Memorial 10.33 Berinsfield Interchange east 13.25 Abingdon Stratton Way 10.35 Drayton St Leonard Memorial 13.30 ENTIRE SERVICE UNDER REVIEW Oxfordshire County Council Didcot Town services 91/92/93 Mondays to Saturdays 93 Broadway - West Didcot - Broadway Broadway Market Place ~~ 10.00 11.00 12.00 13.00 14.00 Meadow Way 09.05 10.05 11.05 12.05 13.05 14.05 Didcot Hospital 09.07 10.07 11.07 12.07 13.07 14.07 Freeman Road 09.10 10.10 11.10 12.10 13.10 14.10 Broadway Market Place 09.15 10.15 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ Broadway, Park Road, Portway, Meadow Way, Norreys Road, Drake Avenue, Wantage Road, Slade Road, Freeman Road, Brasenose Road, Foxhall Road, Broadway 91 Broadway - Parkway - Ladygrove - The Oval - Broadway Broadway Market Place 09.15 10.15 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 Orchard Centre 09.17 10.17 11.17 12.17 13.17 14.17 Didcot Parkway 09.21 10.21 11.21 12.21 13.21 14.21 Ladygrove Trent Road 09.25 10.25 11.25 12.25 13.25 14.25 Ladygrove Avon Way 09.29 10.29 11.29 12.29 13.29 14.29 The Oval 09.33 10.33 11.33 12.33 13.33 14.33 Didcot Parkway 09.37 -

Early Medieval Oxfordshire

Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire Sally Crawford and Anne Dodd, December 2007 1. Introduction: nature of the evidence, history of research and the role of material culture Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire has been extremely well served by archaeological research, not least because of coincidence of Oxfordshire’s diverse underlying geology and the presence of the University of Oxford. Successive generations of geologists at Oxford studied and analysed the landscape of Oxfordshire, and in so doing, laid the foundations for the new discipline of archaeology. As early as 1677, geologist Robert Plot had published his The Natural History of Oxfordshire ; William Smith (1769- 1839), who was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire, determined the law of superposition of strata, and in so doing formulated the principles of stratigraphy used by archaeologists and geologists alike; and William Buckland (1784-1856) conducted experimental archaeology on mammoth bones, and recognised the first human prehistoric skeleton. Antiquarian interest in Oxfordshire lead to a number of significant discoveries: John Akerman and Stephen Stone's researches in the gravels at Standlake recorded Anglo-Saxon graves, and Stone also recognised and plotted cropmarks in his local area from the back of his horse (Akerman and Stone 1858; Stone 1859; Brown 1973). Although Oxford did not have an undergraduate degree in Archaeology until the 1990s, the Oxford University Archaeological Society, originally the Oxford University Brass Rubbing Society, was founded in the 1890s, and was responsible for a large number of small but significant excavations in and around Oxfordshire as well as providing a training ground for many British archaeologists. Pioneering work in aerial photography was carried out on the Oxfordshire gravels by Major Allen in the 1930s, and Edwin Thurlow Leeds, based at the Ashmolean Museum, carried out excavations at Sutton Courtenay, identifying Anglo-Saxon settlement in the 1920s, and at Abingdon, identifying a major early Anglo-Saxon cemetery (Leeds 1923, 1927, 1947; Leeds 1936). -

Commander Ship Port Tons Mate Gunner Boatswain Carpenter Cook

www.1812privateers.org ©Michael Dun Commander Ship Port Tons Mate Gunner Boatswain Carpenter Cook Surgeon William Auld Dalmarnock Glasgow 315 John Auld Robert Miller Peter Johnston Donald Smith Robert Paton William McAlpin Robert McGeorge Diana Glasgow 305 John Dal ? Henry Moss William Long John Birch Henry Jukes William Morgan William Abrams Dunlop Glasgow 331 David Hogg John Williams John Simpson William James John Nelson - Duncan Grey Eclipse Glasgow 263 James Foulke Martin Lawrence Joseph Kelly John Kerr Robert Moss - John Barr Cumming Edward Glasgow 236 John Jenkins James Lee Richard Wiles Thomas Long James Anderson William Bridger Alexander Hardie Emperor Alexander Glasgow 327 John Jones William Jones John Thomas William Thomas James Williams James Thomas Thomas Pollock Lousia Glasgow 324 Alexander McLauren Robert Caldwell Solomon Piike John Duncan James Caldwell none John Bald Maria Glasgow 309 Charles Nelson James Cotton? John George Thomas Wood William Lamb Richard Smith James Bogg Monarch Glasgow 375 Archibald Stewart Thomas Boutfield William Dial Lachlan McLean Donald Docherty none George Bell Bellona Greenock 361 James Wise Thomas Jones Alexander Wigley Philip Johnson Richard Dixon Thomas Dacers Daniel McLarty Caesar Greenock 432 Mathew Simpson John Thomson William Wilson Archibald Stewart Donald McKechnie William Lee Thomas Boag Caledonia Greenock 623 Thomas Wills James Barnes Richard Lee George Hunt William Richards Charles Bailey William Atholl Defiance Greenock 346 James McCullum Francis Duffin John Senston Robert Beck -

Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxford Archdeacons’ Marriage Bond Extracts 1 1634 - 1849 Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1634 Allibone, John Overworton Wheeler, Sarah Overworton 1634 Allowaie,Thomas Mapledurham Holmes, Alice Mapledurham 1634 Barber, John Worcester Weston, Anne Cornwell 1634 Bates, Thomas Monken Hadley, Herts Marten, Anne Witney 1634 Bayleyes, William Kidlington Hutt, Grace Kidlington 1634 Bickerstaffe, Richard Little Rollright Rainbowe, Anne Little Rollright 1634 Bland, William Oxford Simpson, Bridget Oxford 1634 Broome, Thomas Bicester Hawkins, Phillis Bicester 1634 Carter, John Oxford Walter, Margaret Oxford 1634 Chettway, Richard Broughton Gibbons, Alice Broughton 1634 Colliar, John Wootton Benn, Elizabeth Woodstock 1634 Coxe, Luke Chalgrove Winchester, Katherine Stadley 1634 Cooper, William Witney Bayly, Anne Wilcote 1634 Cox, John Goring Gaunte, Anne Weston 1634 Cunningham, William Abbingdon, Berks Blake, Joane Oxford 1634 Curtis, John Reading, Berks Bonner, Elizabeth Oxford 1634 Day, Edward Headington Pymm, Agnes Heddington 1634 Dennatt, Thomas Middleton Stoney Holloway, Susan Eynsham 1634 Dudley, Vincent Whately Ward, Anne Forest Hill 1634 Eaton, William Heythrop Rymmel, Mary Heythrop 1634 Eynde, Richard Headington French, Joane Cowley 1634 Farmer, John Coggs Townsend, Joane Coggs 1634 Fox, Henry Westcot Barton Townsend, Ursula Upper Tise, Warc 1634 Freeman, Wm Spellsbury Harris, Mary Long Hanburowe 1634 Goldsmith, John Middle Barton Izzley, Anne Westcot Barton 1634 Goodall, Richard Kencott Taylor, Alice Kencott 1634 Greenville, Francis Inner