UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Left out in Los Angeles THESIS Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No. CF No. Adopted Community Plan Area CD Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 08/06/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 3 Woodland Hills - West Hills 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue & 7157 08/06/1962 Sunland - Tujunga - Lake View 7 Valmont Street Terrace - Shadow Hills - East La Tuna Canyon 3 Plaza Church 535 North Main Street and 100-110 08/06/1962 Central City 14 La Iglesia de Nuestra Cesar Chavez Avenue Señora la Reina de Los Angeles (The Church of Our Lady the Queen of Angels) 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill Street 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Dismantled May 1969; Moved to Hill Street between 3rd Street and 4th Street, February 1996 5 The Salt Box 339 South Bunker Hill Avenue (Now 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Moved from 339 Hope Street) South Bunker Hill Avenue (now Hope Street) to Heritage Square; destroyed by fire 1969 6 Bradbury Building 300-310 South Broadway and 216- 09/21/1962 Central City 14 224 West 3rd Street 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho 10940 North Sepulveda Boulevard 09/21/1962 Mission Hills - Panorama City - 7 Romulo) North Hills 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 09/21/1962 Silver Lake - Echo Park - 1 Elysian Valley 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/02/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 12 Woodland Hills - West Hills 10 Eagle Rock Eagle Rock View Drive, North 11/16/1962 Northeast Los Angeles 14 Figueroa (Terminus), 72-77 Patrician Way, and 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road 11 The Rochester (West Temple 1012 West Temple Street 01/04/1963 Westlake 1 Demolished February Apartments) 14, 1979 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 01/04/1963 Hollywood 13 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 01/28/1963 West Adams - Baldwin Hills - 10 Leimert City of Los Angeles May 5, 2021 Page 1 of 60 Department of City Planning No. -

The Demille Apartments 7716 Laurel Canyon Blvd | North Hollywood, CA MATTHEWS REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT SERVICES INVESTMENT REAL ESTATE MATTHEWS

OFFERING MEMORANDUM The DeMille Apartments 7716 Laurel Canyon Blvd | North Hollywood, CA MATTHEWS REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT SERVICES INVESTMENT REAL ESTATE MATTHEWS 2 2 | APARTMENT NAME CONTENTS 04 |PROPERTY OVERVIEW MATTHEWS REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT SERVICES INVESTMENT REAL ESTATE MATTHEWS 06 |AREA OVERVIEW - SAN FERNANDO VALLEY 10 |FINANCIAL OVERVIEW EXCLUSIVELY LISTED BY BRANDON DICKER ASSOCIATE-MULTIFAMILY Direct +1 818 923 6118 Mobile +1 818 523 1754 [email protected] License No. 01958894 (CA) DAVID HARRINGTON EVP & NATIONAL DIRECTOR - MULTIFAMILY Direct +1 310 295 1170 Mobile +1 310 497 5590 [email protected] License No. 01320460 (CA) 3 MATTHEWS REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT SERVICES INVESTMENT REAL ESTATE MATTHEWS 4 Property Overview OPPORTUNITY PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 7716 Laurel Canyon Boulevard presents a unique opportunity to capitalize • 16 Units, Built in 1970 MATTHEWS REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT SERVICES INVESTMENT REAL ESTATE MATTHEWS on a well maintained multifamily property in one of Los Angeles’s most • Tremendous Rent Upside Potential of 83% popular rental markets, North Hollywood. Built in 1970, the building has • Great Mix of One, Two, and Three Bedroom Units been maintained very well and has a quiet and secluded feel. With central AC, heating, and on-site laundry, tenants are provided with the essentials • Building Size of 14,979 Square Feet and amenities of living in a prime neighborhood. This building will provide • Currently 100% Occupied an investor a great value-add opportunity with tremendous upside in rents • Lot Size of 0.45 Acres with R3 Zoning upwards of 89 percent. • Front Structure is Two Stories with 10 units, Back Structure is Two Stories with 6 Units The building consists of 16 units which include six one-bedroom units, • Units Feature Central Air Conditioning nine two-bedroom units, and one three-bedroom unit. -

Community Resource Guide North Hollywood

Community Resource Guide North Hollywood Introduction Comprehensive Community Health Centers, Inc. (CCHC) is a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) and a California Non-Profit Public Benefit Corporation. CCHC is among the top community health center systems in Los Angeles County having grown in health service visits from 45,000 visits in 2004 to over 129,000 visits in 2015. With this guide, CCHC will provide you with the proper resources to help you an your families. What you will find The Community Resource Guide for Comprehensive Community Health Centers is divided into 14 sections. Table of Contents 2-1-1 LA County Infoline………………………………………………………...……………….. Child Support Services………………………………………………………...……………….. Crisis Hotlines………………………………………………………………………………..…… Domestic Violence……………………………………………………………………………….. Employment………………………………………………………………………………….. Food Banks …………………………………………………………………………..…………… Grief & Loss Services ………………………………………………………………………….. Legal Services …………………………………………………………………………..…………... Mental Health …………………………………………………………………………..…….……... Physical Activity …………………………………………………………………………………… Self– Help Groups………………………………………………………………………………….. Shelters ………………………………………….……………………………………..…………… Substance Abuse………………………………………………………………………………….. Utility Services………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 2-1-1 LA County– Infoline 3 2-1-1 LA County Infoline Website: www.healthcity.com Services: Dial 2-1-1 from any area code for free 24-hr multilingual information & referrals to human services. Referrals are available for domestic violence, -

ANALYSIS of EXISTING CONDITIONS a Subregional View Of

ANALYSIS OF EXISTING CONDITIONS A subregional view of travel on the Westside has been drawn from interviews with elected officials, meetings with MTA and other agencies and analysis of existing data. The subregion considered in this analysis is shown in Figure 1. Because transportation does not respect political boundaries, the Westside Mobility Study area is roughly all of Los Angeles County west of La Brea Avenue, north of Los Angeles International Airport and south of Mulholland Drive. The Westside has many of the most important activity centers in all of Southern California; 16 of these are shown in Figure 2. The Westside Mobility Study has begun to define what might be done to meet those needs for improved linkages, specifying the most critical locations for major transit improvements and other multimodal improvements. Evaluation of Existing Transportation Conditions A goal of the Westside Mobility Study is to provide an accurate picture of the existing traffic and congestion levels on primary arterials and corridors in the Westside area. As there was a large amount of readily available, current data, no new supplementary traffic counts were conducted. Data was acquired from the following sources and ranges predominantly from 2000 to the present day: · Traffic data from the Cities of Beverly Hills, Culver City, Santa Monica and West Hollywood · Transit data from Culver City Bus, Big Blue Bus and MTA · Information from MTA’s Short Range Transportation Plan: Technical Document · Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT) database of traffic counts · Previous Kaku Associates projects · Caltrans counts 10 WESTSIDE MOBILITY STUDY SSOCI TES A Corporation FIGURE 1 STUDY AREA Multi-purpose Activity Centers WESTSIDE MOBILITY STUDY SSOCI TES A Corporation FIGURE 2 MAJOR ACTIVITY CENTERS Area Characteristics - Employment, Population and Housing: The Westside area has at least 10% of the jobs in Los Angeles County and is home to over 6% of County residents. -

Locations & Hours

Locations & Hours | Los Angeles Public Library http://www.lapl.org/branches/ GET A LIBRARY CARD | MY LIBRARY ACCOUNT Library Catalog Keyword Collections & Resources Locations & Hours What's On? Get Involved About LAPL Library Store Locations & Hours Locations & Hours Print this page Locations & Hours Holiday Closures Facility Rentals Central Library Docent Tours (Central) Español Get Your Diploma Kids & Parents Teens Teachers Job Seekers Adult Literacy Citizenship Veterans Resources Health Matters Search Results Show all Branches Money Matter$ Click branch name for details Find a Library Online Learning Distance / Proximity Central Library Show on Map ADA Services Postal code Weekend Street Closures around Central Library How Do I? 630 W. 5th Street Distance (Miles) Los Angeles, CA 90071 My Library Account (213) 228-7000 3 Reserve a Computer Mon: 10-8, Tue: 10-8, Wed: 10-8, Thu: 10-8, Fri: 9:30-5:30 Sat: 9:30-5:30, Sun: 1-5 Resources & Services Ask a Librarian - Any - Book a Librarian Angeles Mesa Branch Library Show on Map Find It Find A Library 2700 W. 52nd Street Los Angeles, CA 90043 (323) 292-4328 Follow LAPL Mon: 10-8, Tue: 12-8, Wed: 10-8, Thu: 12-8, Fri: 9:30-5:30 Related Information Sat: 9:30-5:30, Sun: Closed Cheryl Collins, Director, Branch Library Services Arroyo Seco Regional Library Show on Map Kren Malone, Director, Central Library Services 6145 N. Figueroa Street Los Angeles, CA 90042 Holiday Closures (323) 255-0537 Friends Groups Meeting Room Rentals Mon: 10-8, Tue: 10-8, Wed: 10-8, Thu: 10-8, Fri: 9:30-5:30 Map of Branches (PDF) Sat: 9:30-5:30, Sun: 1-5 Ascot Branch Library Show on Map Other Local Libraries 120 W. -

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No.CF No. Adopted Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 8/6/1962 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue 8/6/1962 3 Nuestra Senora la Reina de Los 100-110 Cesar E. Chavez Ave 8/6/1962 Angeles (Plaza Church) & 535 N. Main St 535 N. Main Street & 100-110 Cesar Chavez Av 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill8/6/1962 Dismantled 05/1969; Relocated to Hill Street Between 3rd St. & 4th St. in 1996 5 The Salt Box (Former Site of) 339 S. Bunker Hill Avenue 8/6/1962 Relocated to (Now Hope Street) Heritage Square in 1969; Destroyed by Fire 10/09/1969 6 Bradbury Building 216-224 W. 3rd Street 9/21/1962 300-310 S. Broadway 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho Romulo) 10940 Sepulveda Boulevard 9/21/1962 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 9/21/1962 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/2/1962 10 Eagle Rock 72-77 Patrician Way 11/16/1962 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road Eagle Rock View Drive North Figueroa (Terminus) 11 West Temple Apartments (The 1012 W. Temple Street 1/4/1963 Rochester) 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 1/4/1963 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 1/28/1963 14 Chatsworth Community Church 22601 Lassen Street 2/15/1963 (Oakwood Memorial Park) 15 Towers of Simon Rodia (Watts 10618-10626 Graham Avenue 3/1/1963 Towers) 1711-1765 E. 107th Street 16 Saint Joseph's Church (site of) 1200-1210 S. -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Left out in Los Angeles Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7nq0m4s2 Author Smith, Tyler Reese Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Left Out in Los Angeles THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF URBAN & REGIONAL PLANNING in Social Ecology by Tyler Reese Smith Thesis Committee: Associate Professor Douglas Houston, Chair Assistant Professor Jae Hong Kim Associate Professor Walter Nicholls 2016 © TYLER REESE SMITH 2016 DEDICATION This research is dedicated to all the people on the streets and those experiencing instability in their lives, may you continue forward with your strength and see the light at the end of the tunnel. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES v LIST OF TABLES vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vii ABSTRACT viii INTRODUCTION 1 1. RESEARCH OBJECTIVES 3 1.1 BUILDING ON PREVIOUS RESEARCH 3 1.2 FRAMING RESEARCH THROUGH AN URBAN PLANNING CONTEXT 7 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 10 2.1 CONTROL & CATEGORIZATION OF SPACE 10 2.2 SPATIAL FEATURES OF ENCAMPMENTS 10 2.3 SPATIAL EXCLUSION 14 2.4 CRIMINALIZATION OF HOMELESSNESS IN LOS ANGELES 16 3. METHODOLOGY 20 3.1 ENHANCING THE TYPOLOGY 21 a. SPACES OF RESOURCES & CONSUMPTION 21 b. SPACES OF CHARITY & SERVICES 22 c. SPACES OF MOBILITY 22 d. SPACES OF RELIEF & REST 22 e. SPACES OF EXCLUSION & SURVEILLANCE 23 f. URBAN MORPHOLOGY 24 3.2 GIS MAPPING 25 3.3 SITE VISITS 28 3.4 SCORING MATRIX 31 4. -

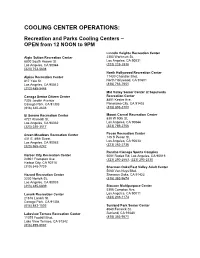

Cooling Center Operations

COOLING CENTER OPERATIONS: Recreation and Parks Cooling Centers – OPEN from 12 NOON to 9PM Lincoln Heights Recreation Center Algin Sutton Recreation Center 2303 Workman St, 8800 South Hoover St Los Angeles, CA 90031 Los Angeles, CA 90044 (323) 225-2838 (323) 753-5808 North Hollywood Recreation Center Alpine Recreation Center 11430 Chandler Blvd. 817 Yale St. North Hollywood, CA 91601 Los Angeles, CA 90012 (818) 763-7651 (213) 485-5448 Mid Valley Senior Center at Sepulveda Canoga Senior Citizen Center Recreation Center 7326 Jordan Avenue 8801 Kester Ave. Canoga Park, CA 91303 Panorama City, CA 91402 (818) 340-2633 (818) 893-3700 El Sereno Recreation Center Mount Carmel Recreation Center 4721 Klamath St, 830 W 90th St, Los Angeles, CA 90032 Los Angeles, CA 90044 (323) 225-3517 (323) 789-2756 Green Meadows Recreation Center Pecan Recreation Center 145 S Pecan St, 431 E. 89th Street Los Angeles, CA 90033 Los Angeles, CA 90083 (323) 262-2736 (323) 565-4242 Rancho Cienega Sports Complex Harbor City Recreation Center 5001 Rodeo Rd, Los Angeles, CA 90016 24901 Frampton Ave. (323) 290-2663, (323) 290-2330 Harbor City, CA 90710 (310) 548-7729 Sherman Oaks/East Valley Adult Center 5060 Van Nuys Blvd. Hazard Recreation Center Sherman Oaks, CA 91423 2230 Norfolk St, (818) 383-9674 Los Angeles, CA 90033 (213) 485-6839 Slauson Multipurpose Center 5306 Compton Ave, Lanark Recreation Center Los Angeles, CA 90011 21816 Lanark St. (323) 233-1174 Canoga Park, CA 91304 (818) 883-1503 Sunland Park Senior Center 8640 Fenwick St. Lakeview Terrace Recreation Center Sunland, CA 91040 11075 Foothill Blvd. -

4.5 Cultural Resources Regulatory Framework

Hollywood Community Plan Update 4.5 Cultural Resources Draft EIR 4.5 CULTURAL RESOURCES This section provides an overview of cultural resources in the Project Area and evaluates the potential impacts on these resources associated with the Proposed Plan. Topics addressed include historical resources, archaeological resources, paleontological resources, human remains and tribal cultural resources. This section was prepared utilizing information from a variety of sources, including the SurveyLA Historic Resources Survey Report prepared for the Hollywood Community Plan Area (CPA) by the Historic Resources Group in August 2011 and revised in November 2015, and the Historic Resources Survey for the Hollywood Redevelopment Project Area prepared by Chattel Architecture, Planning & Preservation, Inc. in February 2010. Information from the Archaeology Information Center at the UCLA Institute of Archaeology, the Natural Museum of Los Angeles County Paleontological Resource Assessment and Mitigation Office and the Thomas W. Dibblee Foundation Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History was used to generally identify the location of archaeological and paleontological resources. Tribal consultation was undertaken in accordance with Assembly Bill (AB) 52 to determine the potential presence of Tribal Cultural Resources in the Project Area. REGULATORY FRAMEWORK Several levels of government maintain jurisdiction over historical resources. The framework for the identification and, in certain instances, protection of historical resources is established at the federal level, while the identification, documentation, and protection of such resources are often undertaken by state and local governments. The principal federal, state, and local laws governing and influencing the preservation of historical resources, as well as the other types of cultural resources are discussed below. -

East Hollywood and Silverlake

5 SANTA CLARITA 14 5 210 Angeles National Forest 118 NORTHRIDGE Laurel Cyn Blvd Vineland Ave O Coldwater Cyn Ave 405 210 VAN NUYS 5 FRANKLIN AVE RESEDA 170 NORTH HOLLYWOOD BURBANK ALTADENA 101 2 RUSSELL AVE 210 101 134 Ventura Blvd 134 210 MELBOURNE AVE Colorado Blvd STUDIO CITY Universal Colorado Blvd 134 Studios Grifth EAGLE ROCK PASADENA Park GLENDALE 2 KINGSWELL AVE 101 110 N WALK AREA OVERVIEW 5 HIGHLAND N 605 HOLLYWOOD BLVD PROSPECT AVE PARK WALK SITES Topanga Sunset Blvd State Park 2 ALHAMBRA HOLLYWOOD S 110 101 u ns Elysian EAST HOLLYWOOD CAMERO AVE CAMERO AVE et Blv RODNEYDR d Park Vermont Ave Vermont EL MONTE S MYRA AVE HOLLYWOOD BLVD o 26 BEVERLY t 1 Vermont /Santa Monica Metro Station o 10 5 LYMAN PL S WINONABLVD t 25 BARNSDALL HILLS Wilshire BlvdBlvd Crenshaw 2 Los Angeles City College (LACC) ART PARK CLAYTON AVE 110 10 3 Family Amusement Corporation/Family Arcade 31 405 710 J EDGEMONT ST KENMORE AVE DOWNTOWN BOYLE 4 11 HILLHURST AVE Union Swapmeet HAROLD WY LOS ANGELES HEIGHTS BARNSDALL AVE MAUBERT AVE CUMBERLAND AVE 101 5 MYRA AVE 60 60 Cahuenga Branch Library 12 32 ROSALIA RD SANTA 10 F MONICA 10 10 6 Historic Route 66 G 30 10 COMMONWEALTH 9 15 35 5 I 7 El Gran Burrito SUNSET BLVD 29 SUNSET DR C re St Soto 8 n Vernon Ave Oldest Structure in East Hollywood s WESTERN AVE WESTERN 13 34 14 h 8 27 33 a 9 Parseghian Photo 36-37 w 405 B Slauson Ave Slauson Ave 5 28 l 110 D-F 38 MARINA v 10 d Immaculate Heart of Mary Church SUNSET BLVD Ave Central O St Figueroa E DE LONGPRE AVE N VIRGIL AVE LYMAN PL BATES AVE LEGEND VIRGIL PL HOOVER ST DEL REY 11 TALMADGE ST Vertebrate Paleontological Site SANBORN AVE DE LONGPRE AVE MANZANITA ST CATALINA ST KENMORE AVE Walk Area 710 12 MARIPOSA AVE Sasoun Bakery VERMONT AVE FERNWOOD AVE 605 NEWHAMPSHIRE AVE C ALEXANDRIA AVE 20 L 22 L RON HUBBARD WAY 13 Falafel Arax Main Walk (E. -

Recommendations to Improve Pedestrian Safety on the Hoopa

RECOMMENDATIONS TO IMPROVE PEDESTRIAN SAFETY IN PACOIMA By Tony Dang, Jaime Fearer, Wendy Alfsen, Caro Jauregui, September 2015 California Walks; Jill Cooper, Katherine Chen, UC Berkeley SafeTREC Recommendations to Improve Pedestrian Safety in Pacoima BY TONY DANG, JAIME FEARER, WENDY ALFSEN, CARO JAUREGUI, CALIFORNIA WALKS; JILL COOPER, KATHERINE CHEN, UC BERKELEY SAFETREC INTRODUCTION The Pacoima neighborhood of the City of Los Angeles was identified as a focus community for a Community Pedestrian Safety Training, in collaboration with Pacoima Beautiful, based on residents’ interest in pedestrian safety and walkability, as well as recent and planned active transportation improvements in and around the neighborhood. Following additional conversations with the Active Transportation Division of the Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT), Los Angeles Walks, Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro), faculty from the Urban and Environmental Policy Institute at Occidental College, and the office of Councilmember Felipe Fuentes, the community invited the University of California at Berkeley’s Safe Transportation Research and Education Center (SafeTREC) and California Walks (Cal Walks) to Pacoima to facilitate a community-driven pedestrian safety action- planning workshop. Cal Walks facilitated the workshop on August 29, 2015, which consisted of: 1) an overview of multidisciplinary approaches to improve pedestrian safety; 2) two walkability assessments along Van Nuys Boulevard and other neighborhood streets; and 3) small group action planning discussions to facilitate the development of community-prioritized recommendations to inform the City’s ongoing active transportation efforts, as well as the County’s planning efforts for the East San Fernando Valley Transit Corridor project. This report summarizes the workshop proceedings, as well as ideas identified during the process and recommendations for pedestrian safety projects, policies, and programs. -

TOTAL $10,316,020,552 34,802 431 N La Cienega Los Angeles 90048 2600-2610 S

With Over 100 Years of Experience, Team Lustig-Bower has Handled Over $10 Billion in Multi-Family Land and Apartment Buildings in the Past 15 Years Alone EXISTING/ PROPERTY ADDRESS CITY PRICE PLANNED UNITS TOTAL $10,316,020,552 34,802 431 N La Cienega Los Angeles 90048 2600-2610 S. Roberston Boulevard Los Angeles 90034 $8,250,000 N/A 14320 Addison Street Sherman Oaks 91423 $19,200,000 56 8601 Glenoaks Boulevard (2020) Sun Valley 91352 $26,200,000 82 5350-5370 Wilshire Boulevard Los Angeles 90036 Confidential N/A 535 S. Kingsley Drive Los Angeles 90020 $34,600,000 72 514 N. Hayworth Avenue Los Angeles 90048 $3,995,000 10 11305 Santa Monica Boulevard Los Angeles 90025 Confidential N/A 464 E. Walnut Street Pasadena 91101 Confidential N/A 2511-2517 W. Sunset Boulevard Los Angeles 90026 Confidential N/A 700 Locust Street Pasadena 91101 $19,350,000 69 21161 Victory Boulevard Canoga Park 91303 Confidential N/A 383 N. Main Street Pomona 91768 Confidential N/A 415, 441, 499 N. Garey Ave. & 109 W. Center St. Pomona 91768 Confidential 140 221 W. Holt Avenue Pomona 91768 Confidential 110 2707 & 2715 Pamoa Road Honolulu 96822 Confidential N/A 7441-7449 Sunset Blvd & 1502-1512 Gardner St Hollywood 90046 Confidential N/A 3731-3761 Stocker Street Los Angeles 90008 $35,000,000 N/A 6036 Variel Avenue Woodland Hills 91367 Confidential N/A 18427 Studebaker Road Cerritos 90703 $48,600,000 150 959 E. Stadium Way Los Angeles 90012 Confidential N/A 125-129 S. Linden Drive Beverly Hills 90212 Confidential N/A 9958-9964 Durant Drive Beverly Hills 90212 Confidential N/A 2033-2101 Virginia Avenue Santa Monica 90404 $13,700,000 40 2225 W.