For Peer Review 19 Inundations of Sand Are Examined

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Formby Civic Socety Newsletter

The Formby Civic Society Newsletter Registered Charity no 516789 October 2012 FORTHCOMING EVENTS Meetings are held at the Ravenmeols Centre, Park Road, Formby, at 8.00 pm on Thursdays General Meetings - 2012 25th October Photography of the Seasons Trevor Davenport 22nd November ‘Fracking’ Prof. Richard Worden 2013 24th January Freshfield Dune Heath T. Jackson and Fiona Sunmer 28th February The Mersey Forest Paul Nolan 28th March The Sack & Bag Industry of Liverpool R. Williams 25th April Annual General Meeting History Group Meetings – 2012 11th October Marshside Fishermen Gladys Armstrong 8th November Ravenmeols Heritage Dr. Reg Yorke 13th December Thomas Fresh, Inspector of Nuisances (from whom ‘Freshfield’ takes its name) Norman Parkinson 2013 10th January Women in WW1 Brenda Murray 14th February Liverpool Children in the 1950s Pamela Russell 14th March Viking finds on Merseyside Robin Philpot 11th April Incredible Liverpool Elizabeth Newell All meetings are now held on Thursdays, starting at 8.00pm, and are open to members (free) and to guests on payment of a small admission charge (£2). SOCIETY NEWS The summer programme culminated with the Heritage Open Day event on 9th September when over 160 1 people visited the site of ‘Formby-by-the-Sea’, many walking the trail from the bottom of Albert Road, where archaeologists were excavating remains of the old promenade, up to Firwood and back by Alexandra Road, viewing the sites of 19th century houses some of which still stand. Other highlights were the walk on Altcar Rifle Range on 11th July over the fields and sand dunes of the Range, with their amazing diversity of wild flowers and plants, on a beautiful summer evening closing with a spectacular sunset, the visit to Townley Hall, Burnley, on 8th August, the wildlife walk on Cabin Hill on 18th August, and an evening walk on 22nd August to the ‘Hakirke’ hidden in the mysterious woods of Crosby Hall. -

FCN April11 Finalb

Formby Civic News The Formby Civic Society Newsletter Registered Charity no 516789 April 2011 Listed Cottage in Peril by Desmond Brennan Inside this issue: Listed Cottage 2 in Peril. Planning 3 Matters. Managing 4 Woodland. Dr Sumner & 3 the Lifeboat. Wildlife Notes. 8 History Group 10 Eccle’s Cottage , Southport Road, 1968; photo M. Sibley. Report. 11 The cottage at 1 Southport Road, known “Outbuildings and Croft”. Reg Yorke Art Group Re- until modern times as Eccles Cottage or suspects the Paradise Lane buildings port. Eccles Farm, is located on the north side were a good deal older than the sole sur- Ravenmeols 12 of the road at its junction with Paradise vivor of this group of buildings. James Heritage Trail. Lane. It dates from the first half of the Eccles paid 7d Tithe to the Rector for his 18th century and is a Grade 2 Listed house and 4d for the “outbuildings”. Formby-by-the 12 Building. The 1968 photograph of the -Sea. After several years of neglect, today building shows at that time it was in rea- Chairman’s 15 finds the building in a parlous state, es- sonable condition, although, even then, Notes the unevenness of the roof indicates that pecially the single story with attic part of all was not well with its timbers. The New Notelets. 15 detail from the 1845 Tithe map (see next page) shows that, in its early days, the cottage was surrounded by an extensive NEW NOTELETS patchwork of fields - very different from today. We know from the information (See page 16) accompanying the map that, at that time, the property was owned by Mary Form- Now available from by and occupied by James Eccles, who Select, Derbyshires, also “occupied” the somewhat longer Ray Derricott or neighbouring cottage further along Para- Tony Bonney dise Lane which he used as Listed Cottage in Peril After several years of neglect, today the building which is believed to be cantly impaired as a result of the tional circumstances may harm to or older than the 2-storey eastern end. -

Podalonia Affinis on the Sefton Coast in 2019

The status and distribution of solitary bee Stelis ornatula and solitary wasp Podalonia affinis on the Sefton Coast in 2019 Ben Hargreaves The Wildlife Trust for Lancashire, Manchester & North Merseyside October 2019 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to Tanyptera Trust for funding the research and to Natural England, National Trust and Lancashire Wildlife Trust for survey permissions. 2 CONTENTS Summary………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 Aims and objectives………………………………………………………………………….6 Methods…………………………………………………………………………………………..6 Results……………………………………………………………………………………………..7 Discussion………………………………………………………………………………………..9 Follow-up work………………………………………………………………………………11 References……………………………………………………………………………………..11 3 SUMMARY The Wildlife Trust for Lancashire, Manchester & North Merseyside (Lancashire Wildlife Trust) were commissioned by Liverpool Museum’s Tanyptera project to undertake targeted survey of Nationally Rare (and regionally rare) aculeate bees and wasps on various sites on the Sefton Coast. Podalonia affinis is confirmed as extant on the Sefton Coast; it is definitely present at Ainsdale NNR and is possibly present at Freshfield Dune Heath. Stelis ornatula, Mimesa bruxellensis and Bombus humilis are not confirmed as currently present at the sites surveyed for this report. A total of 141 records were made (see attached data list) of 48 aculeate species. The majority of samples were of aculeate wasps (Sphecidae, Crabronidae and Pompilidae). 4 INTRODUCTION PRIMARY SPECIES (Status) Stelis ornatula There are 9 records of this species for VC59 between 1975 and 2000. All the records are from the Sefton Coast. The host of this parasitic species is Hoplitis claviventris which is also recorded predominantly from the coast (in VC59). All records are from Ainsdale National Nature Reserve (NNR) and Formby (Formby Point and Ravenmeols Dunes). Podalonia affinis There are 15 VC59 records for this species which includes both older, unconfirmed records and more recent confirmed records based on specimens. -

BOUNDARY COMMISSION for ENGLAND PROCEEDINGS at The

BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND PROCEEDINGS at the 2018 REVIEW OF PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES IN ENGLAND HELD AT THE COTTON EXCHANGE BUILDING, OLD HALL STREET, LIVERPOOL, L3 9JR ON FRIDAY 21 OCTOBER 2016 DAY TWO Before: Mr Neil Ward, The Lead Assistant Commissioner ______________________________ Transcribed from audio by W B Gurney & Sons LLP 83 Victoria Street, London, SW1H 0HW Telephone Number: 0203 585 4721/22 ______________________________ At 9.00 am: THE LEAD ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. Thank you for joining us today. My name is Neil Ward. I am the Lead Assistant Commissioner appointed by the Boundary Commission to conduct two things: To conduct the hearings across the whole of the North West into their Initial Proposals for the revised parliamentary boundaries for the North West region and, along with two fellow assistant Commissioners, Nicholas Elliott and Graeme Clarke, to take on board all the representations that are either made in the hearings or in written representations and to consider, in the light of them, whether we think it is appropriate to recommend changes, revised proposals to the Boundary Commission on their Initial Proposals. I should say that I am, in a sense, essentially independent of the Boundary Commission. Although I am appointed by them, I had no hand in the drafting of the proposals and I received them the same time as everyone else and I am, in a sense, an honest broker in this process, considering whether or not changes ought to be made. This is the second day of the Liverpool hearing. Just a couple of words on process. -

Alt Drainage Act 1779. 59. 61. 88, 91 2 Bolion Improvement Act IR50. 13

INDEX ABBEYS. wMerevalc: Stanlnw: \Vhalley Ashworth, Mr. lauyer. 106-10 Act: of Parliamenc: Atherton (Lanes.). 138 Alt Drainage Act 1779. 59. 61. 88, Attorney-General, 100 91 2 Australia. 172 3: am/ a*f Mannix Bolion Improvement Act IR50. 131. 132 BAKER. William. I Hi Bolton Improvement Art 1864, 137 Bamford, Samuel, 102 Boroughs Incorporation Act 1842, 128 barber, 50 Coroners Act 1832. 116 barlowmen, see burleymen Great and Little Bolton Water Barrett, William. 41 Company Art 1824, 127. 134 Battye, George, 102 4. 109. Ill Libel Acts 1770 92, 117 Bayley, Mr Justice. 110. 113 Municipal Corporations Aet 1835. 32 Belfast (Irei.), 165, 178 Poor law Art 1662. 69 Belmont reservoir (Lanes.), 134, 137, 144 Rivers Pollution Art 1876, 124 Brrr), Henry. 90 Toleration Aet 1689, 56 Best. Mr Justice. 110. 113 Water Art 1945, 145 Birket, river, 198 Waterworks Acts 1847 and 1863. 122 Birmingham, 98, 142-3, 172 Agricola, Gnaeus Julius, 1. 2. 8. 9. 11. 12. Black and Tans, 167 14. 16, 18,'19 Blackburn (Lanes.). 195 Ainsworth, Richard, 139 Blackburn Philanthropic Friendly Society. Aintrec (Lanes.), 60, 62, 81,83 158 Aldborotigh (York;. W.R.), 4 bleaching, 125. 135, 137. 139 alesellers,'49 Blennerhassct (Cumb.), 5 Alexandria (Egypt), 199 Blundell: Alt. river. 60. 63, 89: and see Dirt Alt: Great Henry. 82, 89 Alt; Old Alt Nicholas, 66, 84, 86-7 Altmouth, 71 3, 76,80 Robert, 79 Alt Bridge, 65, 67. 74,81, 84-5. 89-90 Bolsheviks, 171 Alt Grange, j» Altear Bolton (Lanes.), 121, 125, 133, 138. 141 Altrar (lines.), 59, 62, 64- 8, 72. -

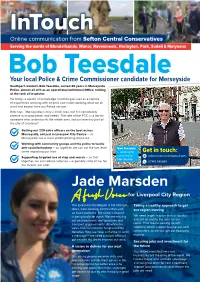

Jade Marsden

InTouch Online communication from Sefton Central Conservatives Serving the wards of Blundellsands, Manor, Ravenmeols, Harington, Park, Sudell & Molyneux Bob Teesdale Your local Police & Crime Commissioner candidate for Merseyside Southport resident, Bob Teesdale, served 30 years in Merseyside Police, almost all of it as an operational uniformed Office; retiring at the rank of inspector. He brings a wealth of knowledge of policing as well as a lifetime of experience working with citizens and understanding what we all want and expect from our Police service. Bob says, “Merseyside is only a small area, but it is remarkably diverse in its population and needs. The role of the PCC, is a job for someone who understands the whole area, not just one tiny part of the city of Liverpool.” Getting our 220 extra officers on the beat across Merseyside, not just in Liverpool City Centre – so Merseyside has a more visible policing presence. Working with community groups and the police to tackle anti-social behaviour – so together, we can cut the low level Bob Teesdale crime impacting our lives. – working to Get in touch: cut crime in Supporting targeted use of stop and search – so that [email protected] Merseyside. together, we can reduce violence – especially knife crime. So 07419 340649 our streets are safer. Jade Marsden A fresh Voice for Liverpool City Region The Liverpool City Region is full of bright Taking a healthy approach to get ideas, hard-working communities and our region moving so much potential. But under Labour it is being badly let down. We are missing We need to get to grips with air quality out on investment, well-paid jobs and and put an end to the jams on our transport improvements. -

Butterfly Recording Report 2020

BUTTERFLY CONSERVATION LANCASHIRE BRANCH DEDICATED TO SAVING WILD BUTTERFLIES, MOTHS AND THEIR HABITATS Lancashire, Manchester and Merseyside Butterfly Recording Report 2020 Butterfly Conservation Registered in England 2206468 Registered Charity 254937 Laura Sivell Butterfly Conservation President Sir David Attenborough Registerd Office Manor Yard, East Lulworth, Wareham, Dorset BH20 5QP President Sir David Attenborough Head Office Manor Yard, East Lulworth, Wareham, Dorset BH205QP Head Office Manor Yard, East Lulworth, Registered in England 2206468 Tel 0870 7744309 Fax 0870 7706150 Registered Charity No 254397Wareham, Dorset BH20 5QP 01929 400209 Email: [email protected] Butterfly Recording Laura Sivell County Butterfly Recorder Please continue to send your butterfly records (remember, every little helps)to: Lancashire and Merseyside Laura Sivell, email [email protected]—note the change of email. Or by post to 22 Beaumont Place, Lancaster LA1 2EY. Phone 01524 69248. Please note that for records to be included in the annual report, the deadline is the end of February. Late records will still be used for the database, but once the report is written, I’m not going to update or rewrite on the basis of late records. The report is also going to have to be written earlier in the year, in February, as I’m full on with work in March/April and I just can’t do it! Greater Manchester These records should only go to Peter Hardy, 28 Hyde Grove, Sale, M33 7TE, email [email protected] - not to Laura Sivell. Some people have been sending their records to both, leading to a fair amount of wasted time in sorting out the duplicate records. -

Formby and Little Altcar Neighbourhood Development Plan

Formby and Little Altcar Neighbourhood Development Plan 2012 to 2030 Page| Page|02 FOREWORD Formby is a great town with a unique heritage and a dynamic future. Its uniqueness is due in part to its open areas of natural beauty, unrivalled coastal dunes and its local heritage. Investment and change in the years ahead will only be worthwhile if it makes a real difference to the lives of local people and the future of its community. The Formby and Little Altcar Neighbourhood Development Plan, [NDP] has been produced jointly by the Parish Councils of Formby and Little Altcar, starting back in September 2013. The Parish Councils wanted the people of Formby and Little Altcar to have a say in all aspects of the future of the town; addressing the issues surrounding housing, infrastructure, health and wellbeing, the environment, and natural/heritage assets. However, most importantly, it wanted local people to decide what they wanted in their community. The NDP sets out a vision for the area that reflects the thoughts and feelings of local people with a real interest in their community. It sets out objectives on key themes such as housing, employment, green space, moving around and community facilities and builds on current and future planned activities. The Parish Councils are committed to developing and strengthening contacts with the groups that have evolved because of the NDP process. We believe that by working together to implement the NDP it will make Formby an even better place to live, work and enjoy. We have had to ensure that our NDP is consistent, where appropriate, with the Sefton Local Plan, the February 2019 National Planning Policy Framework, subsequent updates, and guidance notes. -

57. Sefton Coast Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 57. Sefton Coast Area profile: Supporting documents www.naturalengland.org.uk 1 National Character 57. Sefton Coast Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper,1 Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention,3 we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas North (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which East follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. Yorkshire & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform West their decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a East landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage Midlands broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will West also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Midlands East of Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features England that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each London area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental South East Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. South West The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. -

Sefton Council Election Results 1973-2012

Sefton Council Election Results 1973-2012 Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher The Elections Centre Plymouth University The information contained in this report has been obtained from a number of sources. Election results from the immediate post-reorganisation period were painstakingly collected by Alan Willis largely, although not exclusively, from local newspaper reports. From the mid- 1980s onwards the results have been obtained from each local authority by the Elections Centre. The data are stored in a database designed by Lawrence Ware and maintained by Brian Cheal and others at Plymouth University. Despite our best efforts some information remains elusive whilst we accept that some errors are likely to remain. Notice of any mistakes should be sent to [email protected]. The results sequence can be kept up to date by purchasing copies of the annual Local Elections Handbook, details of which can be obtained by contacting the email address above. Front cover: the graph shows the distribution of percentage vote shares over the period covered by the results. The lines reflect the colours traditionally used by the three main parties. The grey line is the share obtained by Independent candidates while the purple line groups together the vote shares for all other parties. Rear cover: the top graph shows the percentage share of council seats for the main parties as well as those won by Independents and other parties. The lines take account of any by- election changes (but not those resulting from elected councillors switching party allegiance) as well as the transfers of seats during the main round of local election. -

Formby Civic News

Formby Civic News The Formby Civic Society Newsletter Registered charity No 516789 FORMBY’S FIRST BLUE PLAQUE May 2015 Contents In November 2014, one of the the building of the railway station Society’s projects came to fruition which then took his name and which after months of planning and hard became the name of the whole local History Group 2 Report work; a joint project with the community. He improved and Chartered Institute of developed agriculture in this area, Railway 3 Crossings Environmental Health. but his reputation extends to being Assets of 5 one of Liverpool’s mid-19th century Community Value Environmental Health heroes. The Formby Home 7 Front 1914 - 18 He lived at this address between Laxton Cottage 8 1853 and 1857. Originally a Summer 9 Programme Wildlife Notes 10 AGM 2015 13 A Blue Plaque was fixed to the front FCS Flickr Archive 14 wall of Freshfield House, 95 FCS Programme 16 Freshfield Road, the former home of Thomas Fresh, the 'founder' of farmhouse, it stood at the Northern Freshfield. The historic house is now end of Four Acre Lane at its WHY NOT the home of Barbara and Charles intersection with Hill’s Lane, (now JOIN IN SOME Jackson. known as Grange Lane). Four Acre OF THE Lane was then extended round the Thomas Fresh was responsible for ACTIVITIES IN East end of the house to provide OUR SUMMER access to the new railway station and PROGRAMME? thereby took the new name of Freshfield Road. Details of what is on offer can be We are very grateful to the found on back C.I.E.H for their financial page! support. -

Mental Health Equity Profile Mersey Care NHS Trust Final Report

Mental Health Equity Profile for the Mersey Care NHS Trust catchment area Final report Janet Ubido and Cath Lewis Liverpool Public Health Observatory Report series No.69, September 2008 Mental Health Equity Profile for the Mersey Care NHS Trust catchment area Final report Janet Ubido and Cath Lewis Liverpool Public Health Observatory Report series No.69, September 2008 ISBN 1 874038 66 X The full report and executive summary can be found on the Liverpool Public Health Observatory website at www.liv.ac.uk/PublicHealth/obs Alternatively, printed copies can be obtained by contacting Francesca Bailey at the Observatory on 0151 794 5570. Any queries regarding the content of the report, please contact Janet Ubido ([email protected]) or Cath Lewis ([email protected]). Liverpool Public Health Observatory Steering Group Hannah Chellaswamy, Sefton PCT Catherine Reynolds, Liverpool PCT Val Upton, Liverpool PCT Sam McCumiskey, Mersey Care NHS Trust Ruth Butland, Mersey Care NHS Trust Mathew Ashton, Knowsley PCT Ian Atkinson, independent consultant Alex Scott-Samuel, Liverpool Public Health Observatory Cath Lewis, Liverpool Public Health Observatory Janet Ubido, Liverpool Public Health Observatory Carol Adebayo, Liverpool PCT Acknowledgements Val Upton, Liverpool PCT Michael Morris, Mersey Care NHS Trust Ann Deane, Mersey Care NHS Trust Stephanie White, Mersey Care NHS Trust Sophie Archard, Mersey Care NHS Trust Charlotte Chattin, Sefton PCT Neil Potter, North West Public Health Observatory (NWPHO) Dan Hungerford and Zara Anderson, Trauma