Pacific Northwest Logistics Patterns: the Port of Prince Rupert As a Successful National Gateway Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Port of Prince Rupert Delivers Another Record Year

Port of Prince Rupert Delivers Another Record Year rupertport.com The Prince Rupert Port Authority (PRPA) announced today another record year in volume. A grand total of 29.9 million tonnes of cargo moved through the Port of Prince Rupert in 2019 – 12% more than the 26.7 million tonnes handled the previous year and the highest total volume to date for the Port. Supporting the overall positive trend was strong Follow the BCMEA performance at DP World’s Fairview Container Terminal with over 1.2 million TEUs at an increase on social media of 17% over 2018, the addition of propane volume through AltaGas’ Ridley Island Propane Export Terminal, and growth in coal handled at Ridley Terminal where cargo levels were up 18% over the previous year. (continued) We’re looking for your good news stories to share! Please submit to Grace Sullivan: [email protected] 500 – 349 Railway Street, Vancouver, British Columbia V6A 1A4 604.688.1155 www.bcmea.com January 16, 2020 The BCMEA Bulletin January 16, 2020 Port of Prince Rupert Delivers Another Record Year (continued) Northland Cruise Terminal also saw a year-over-year increase in passenger volumes of 35%, totalling over 12,400 visitors to Prince Rupert through cruise travel. “The Port of Prince Rupert’s consistent record-breaking annual volumes confirms the Port’s growing role in Canadian trade,” said Shaun Stevenson, President and CEO of the Prince Rupert Port Authority. “The Port of Prince Rupert has a reputation for offering strategic advantages to shippers. The 2019 volumes illustrate the growing market demand for the Prince Rupert gateway and further validates our plans for growth and expansion over the next several years.” PRPA’s latest economic impact study released in 2019 revealed that port-related growth has resulted in the Port of Prince Rupert handling approximately $50 billion in trade value annually and supports an estimated 3,600 direct supply-chain jobs in northern BC, $310 million in annual wages, and $125.5 million in annual government revenue. -

Alternatives Analysis

Alternatives Analysis BHP Proposed Grays Harbor Potash Export Facility Hoquiam, Washington 40600-HS-RPT-55047 Revision 2 17 June 2019 Submitted by WSP USA 33301 Ninth Avenue South, Suite 300 Federal Way, Washington 98003-2600 WA17.0202.00 ALTERNATIVES ANALYSIS BHP PROPOSED GRAYS HARBOR POTASH EXPORT FACILITY TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Proposed Facility Overview ............................................................................. 2 2.0 ALTERNATIVES ANALYSIS PROCESS ............................................................ 4 2.1 Section 404(b)(1) Background ......................................................................... 4 2.2 Analysis Process .............................................................................................. 4 3.0 PHASE 1 – NEED, PURPOSE, AND GEOGRAPHIC AREA............................... 6 3.1 Step 1: Project Need ......................................................................................... 6 3.2 Step 2: Basic Project Purpose and Water Dependency ................................. 7 3.2.1 Purpose ................................................................................................................. 7 3.2.2 Water Dependency ............................................................................................... 7 3.3 Step 3: Overall Project Purpose and Geographic Area Selection ................. 8 4.0 PHASE 2 - ALTERNATIVES IDENTIFICATION -

Port of Vancouver Supply Chain System

PORT OF VANCOUVER SUPPLY CHAIN SYSTEM James Ireland Bachelor of Commerce, University of British Columbia, 1977 PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION In the Faculty of Business Administration Executive MBA O James Ireland 2005 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2005 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: James Ireland Degree: Master of Business Administration Title of Project: Port of Vancouver Supply Chain System Supervisory Committee: Senior Supervisor Michael Parent, Associate Professor Second Reader Carolyne F. Smart, Associate Professor Date Approved: SIMON FRASER $$&2Q? UN~VERSWY~ibra ry DECLARATION OF PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection, and, without changing the content, to translate the thesislproject or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. The author has further agreed that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by either the author or the Dean of Graduate Studies. -

How People Green the Port: Sustainability in Canadian Ports

How People Green the Port: Sustainability in Canadian Ports by Kristianne R. Hendricks B.A., University of the Fraser Valley, 2014 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Geography Faculty of Environment Kristianne Rebecca Hendricks 2017 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2017 Approval Name: Kristianne Rebecca Hendricks Degree: Master of Arts Title: How People Green the Ports: Sustainability in Canadian Ports Examining Committee: Chair: Meg Holden Associate Professor Peter Hall Senior Supervisor Professor Roger Hayter Supervisor Professor Adolf Ng External Examiner Professor Asper School of Business University of Manitoba Date Defended/Approved: April 4, 2017 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract Canadian Port Authorities (CPAs) annually move $162 billion in international trade and in recent years have been faced with significant pressures to become environmentally sustainable. In response, CPAs have introduced numerous greening strategies with important implications for the dock labour force. This thesis focuses on the greening strategies undertaken by CPAs and their interplay with dockworkers; it identifies these greening strategies and assesses their implications for dockworkers. The thesis adopts a two-part methodology. First, greening measures undertaken by CPAs are categorized and compared. Second, a case study of Vancouver’s port is undertaken through interviews with a broad set of port actors in order to examine the links between labour and sustainability in the port. It is concluded that greening strategies have been an important, albeit uneven trend across CPAs and that dockworkers play an influential role in the greening of the port. Keywords: Canadian Ports; Environmental Sustainability; Labour; Vancouver iv Dedication To the three people who inspire me to keep learning every day: Shaleena, Adalia, and Zoren. -

About the Port of Vancouver Usa

ABOUT THE PORT OF VANCOUVER USA The Port of Vancouver USA, the second-largest port on the Columbia River and an invaluable partner to a broad range of shippers and manufacturers, is a thriving West Coast seaport offering the most direct cargo shipping route from the Pacific Rim to North America through its Advantaged Supply Chain. Unique to the Port of Vancouver USA is its capacity for growth – both on the marine and industrial sides. The port has invested millions of dollars to develop the infrastructure and site requirements needed for companies to transport their cargoes and conduct their businesses in the most efficient and cost-effective manner. The port has worked diligently to provide outstanding customer service and to ensure that what’s important to shippers and tenants – whether specialized equipment, skilled labor, warehousing, sustainability programs, or collaboration on site selection, funding or logistics – is available to meet their needs now and in the future should they wish to expand. QUICK FACTS & HIGHLIGHTS The port, which celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2012, is the third largest port in the state of Washington. It has five marine terminals that provide 13 deepwater shipping berths. The port handled 4.6 million metric tons of cargo in 2012, more than 57 percent in grain exports. However, an increase in the number of grain elevators on the Columbia Snake River System and an increase in agricultural exports from countries such as Australia resulted in less wheat moving across Port of Vancouver docks in 2012. And because wheat is the port’s number one export by volume, the decrease in wheat exports is directly reflected in the 18.5 percent decrease in the port’s overall tonnage from 2011. -

Chapter 5: Freight Rail

Chapter 5: Freight Rail Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Wisconsin’s Rail Freight Network ............................................................................................................. 3 History of freight rail in Wisconsin ........................................................................................................ 3 WisDOT’s response to changes in statewide freight rail service .......................................................... 4 Milwaukee Road ................................................................................................................................... 4 Rail Transit Commissions ...................................................................................................................... 4 Wisconsin’s current freight rail network .............................................................................................. 5 Freight rail classifications ...................................................................................................................... 5 Commodities moved ............................................................................................................................. 6 2030 freight shipments forecast ........................................................................................................... 8 Wisconsin’s intermodal facilities ....................................................................................................... -

The Port of Portland's Marine Operations

The Port of Portland’s Marine Operations The Local Economic Benefits of Worldwide Trade Prepared for: August 2013 Contact Information Ed MacMullan, John Tapogna, Sarah Reich, and Tessa Krebs of ECONorthwest prepared this report. ECONorthwest is solely responsible for its content. ECONorthwest specializes in economics, planning, and finance. Established in 1974, ECONorthwest has over three decades of experience helping clients make sound decisions based on rigorous economic, planning and financial analysis. For more information about ECONorthwest, visit our website at www.econw.com. For more information about this report, please contact: Ed MacMullan Senior Economist 99 W. 10th Ave., Suite 400 Eugene, OR 97401 541-687-0051 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... ES-1 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 2 Global Trade, Local Benefits ...................................................................................... 3 3 Intermodal Transportation Efficiencies .................................................................... 9 4 The Auto-Transport Story .......................................................................................... 10 5 The Potash Story ........................................................................................................ 12 6 The Portland Shipyard Story .................................................................................... -

Eastern Canada Ports Battle for Mega-Ship Calls Peter Ford, Principal, Skyrock Advisors, LLC, and Dr

Analysis: Eastern Canada ports battle for mega-ship calls Peter Ford, principal, SkyRock Advisors, LLC, and Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue, professor of global studies & geography, Hofstra University May 23, 2018 3:59PM EDT The Port of Montreal is the largest on Canada's east coast. [Photo credit: Port of Montreal.] Every new terminal or port development has risks, particularly in a mature market with established stakeholders. The risk can be mitigated if container volumes have a pronounced upward trend, but the financial crisis of 2007-2008 has shifted growth expectations closer to the range of 2 to 3 percent annual growth rate at the global level, but around 5 percent for the North American East Coast. Still, these figures are subject to caution considering growing trade contentions as well as technological changes in global manufacturing and supply chains with the outsourcing and offshoring model being reconsidered. Ocean carriers have responded to this environment by unprecedented industry consolidation, with more merger and acquisition activity happening in the last three years than in the decade preceding, and then further consolidating into mega-alliances with lines focusing on larger vessels to create scale economies and reduce slot costs. Many shipping lines are also involved in container terminal operations with various concession and ownership schemes. 1. All is not quiet on the East Coast front The Canadian East Coast has been a very stable market in the last 50 years with established ports, mainly Montreal and Halifax, assuming dominance. While Montreal experienced a growth relatively on par with the US East Coast, the volumes handled by Halifax barely changed in the last 20 years but have recently shown sign of upward momentum due to new services. -

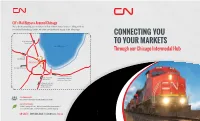

Connecting You to Your Markets

CN's Rail Bypass Around Chicago We've been connecting our customers to their markets faster for years. Along with our streamlined interchange points, we offer a truly efficient supply chain advantage. CONNECTING YOU to Vancouver and Prince Rupert TO YOUR MARKETS Lake Michigan Through our Chicago Intermodal Hub to the U.S. Midwest CHICAGO CN’s bypass rail line to Toronto and the east to Decatur and coast ports of Montreal, Indianapolis Halifax and Saint John to Memphis and the Gulf ports of Mobile and New Orleans CUSTOMER SERVICE One point of contact for all your supply chain needs. OUR GREEN PROMISE CN Rail is energy efficient. We are committed to environmental initiatives that make us the best choice for greener shipping. CN SALES | 1-888-668-4626 | [email protected] | cn.ca CN012020 Port of Prince Rupert Port of Vancouver Port of Halifax Port of The superior network solution Montreal Toronto NY/NJ for all your supply chain logistics Chicago Philadelphia CN provides a one-stop shop, including freight forwarding to Wilmington move your product along the best supply chain routes. Through our partnerships with ocean carriers and major Canadian port gateways, we offer a single line seamless service from last port of call in Asia to Chicago in only 16 days. Port of Mobile Port of New Orleans • 23 intermodal terminals across North America PORT OF PORT OF PORT OF PORT OF PORT OF PORT OF TRANSIT TIME Prince Rupert Vancouver Montreal Halifax New Orleans Mobile • Network reach to 3 coasts serving multiple TORONTO 5th am 5th am same day pm 2nd am 3rd pm 3rd pm Canadian and U.S. -

Study of U.S. Inland Containerized Cargo Moving Through Canadian and Mexican Seaports

Study of U.S. Inland Containerized Cargo Moving Through Canadian and Mexican Seaports July 2012 Committee for the Study of U.S. Inland Containerized Cargo Moving Through Canadian and Mexican Seaports Richard A. Lidinsky, Jr. - Chairman Lowry A. Crook - Former Chief of Staff Ronald Murphy - Managing Director Rebecca Fenneman - General Counsel Olubukola Akande-Elemoso - Office of the Chairman Lauren Engel - Office of the General Counsel Michael Gordon - Office of the Managing Director Jason Guthrie - Office of Consumer Affairs and Dispute Resolution Services Gary Kardian - Bureau of Trade Analysis Dr. Roy Pearson - Bureau of Trade Analysis Paul Schofield - Office of the General Counsel Matthew Drenan - Summer Law Clerk Jewel Jennings-Wright - Summer Law Clerk Foreword Thirty years ago, U.S. East Coast port officials watched in wonder as containerized cargo sitting on their piers was taken away by trucks to the Port of Montreal for export. At that time, I concluded in a law review article that this diversion of container cargo was legal under Federal Maritime Commission law and regulation, but would continue to be unresolved until a solution on this cross-border traffic was reached: “Contiguous nations that are engaged in international trade in the age of containerization can compete for cargo on equal footings and ensure that their national interests, laws, public policy and economic health keep pace with technological innovations.” [Emphasis Added] The mark of a successful port is competition. Sufficient berths, state-of-the-art cranes, efficient handling, adequate acreage, easy rail and road connections, and sophisticated logistical programs facilitating transportation to hinterland destinations are all tools in the daily cargo contest. -

Underwater Noise Management Plan

Underwater noise management plan December 2020 Vancouver Fraser Port Authority Vancouver Fraser Port Authority Underwater noise management plan Contents Purpose ............................................................................................................................................ 1 About the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority and the Port of Vancouver .......................................... 2 Vancouver Fraser Port Authority ............................................................................................... 2 Port of Vancouver ...................................................................................................................... 2 Underwater noise at the Port of Vancouver ..................................................................................... 4 Why is underwater noise a concern? ........................................................................................ 4 Spotlight: Southern resident killer whales ................................................................................. 5 Port-related sources of underwater noise ................................................................................. 6 Our approach to managing and reducing underwater noise ............................................................ 7 Collaboration .............................................................................................................................. 7 Programs and processes .......................................................................................................... -

Revisiting Port Capacity: a Practical Method for Investment and Policy Decisions

Revisiting Port Capacity: A practical method for Investment and Policy decisions Ioannis N. Lagoudis Head of R&D, XRTC Ltd, Business Consultants 95 Akti Miaouli Str., 18538, Piraeus, Greece & Adjunct Faculty, University of the Aegean – Department of Shipping trade and Transport 2A Korai Str., 82100, Chios, Greece and James B. Rice, Jr. Deputy Director, MIT – Center for Transportation and Logistics 1 Amherst Street, Second Floor,Cambridge, MA 02142 Abstract The paper revisits port capacity providing a more holistic approach via including immediate port connections from the seaside and the hinterland. The methodology provided adopts a systemic approach encapsulating the different port terminals along with the seaside and hinterland connections providing a holistic estimation of port capacity. Capacity is defined with the use of two dimensions; static and dynamic. Static capacity relates to land availability or in other words the available space for use. Dynamic capacity is determined by the available technology of equipment in combination to the skill of available labor. With the presentation of a case study from a container terminal the practical use of this methodology is illustrated. Based on the data provided by the terminal operator the results showed that there is still available space to be utilised at a static level and also room more improvement at a dynamic level. The benefits stemming from the above methodology are multidimensional with the key ones being the flexible framework adjusted to the needs of each port system for measuring capacity, the productivity estimation of the different business processes involved in the movement of goods and people and the evaluation of the financial performance of the different business units and the port as a whole.