The Irish in Nineteenth Century Coventry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2020

THE WOODWARD CHARITABLE TRUST 5 April 2010 CHARITY NO: 299963 THE WOODWARD CHARITABLE TRUST ANNUAL REPORT 5 APRIL 2020 The Peak 5 Wilton Road London SW1V 1AP THE WOODWARD CHARITABLE TRUST 5 A p r i l 2 0 20 CONTENTS PAGE 1 The Trustees’ Report 2-15 2 Independent Auditor's Report 16-18 3 Statement of Financial Activities 19 4 Balance Sheet 20 5 Cash Flow Statement 21 6 Notes to the Accounts 22-29 Report and Accounts – 5 April 2020 1 THE WOODWARD CHARITABLE TRUST 5 A p r i l 2 0 20 REPORT OF THE TRUSTEES Legal and Administrative The Woodward Charitable Trust (No. 299963) was established under a Trust Deed dated 26 July 1988. Trustees Mrs C D Woodward Mr S A Woodward Mr T R G Hunniwood Mrs E L D Mills Miss O M V Woodward Miss K M R Woodward (appointed 14 June 2019) Registered The Peak, 5 Wilton Road, London SW1V 1AP Office Website www.woodwardcharitabletrust.org.uk Principal Mrs K Everett Chief Operating Officer (from 11 November 2019) Officers Mrs K Everett Finance Director (to 11 November 2019) Mr R Bell Director (to 11 November 2019) Mrs K Hooper Executive Bankers Child & Co 1 Fleet Street London EC4Y 1BD Solicitors Portrait Solicitors 21 Whitefriars Street London EC4Y 8JJ Auditors Crowe U.K. LLP 55 Ludgate Hill London EC4M 7JW Investment J P Morgan International Bank Limited Advisers 1 Knightsbridge London SW1X 7LX Investment The Trust Deed empowers the Trustees to appoint investment advisers who Powers have discretion to invest the funds of the Trust within guidelines established by the Trustees. -

Download Coventry HLC Report

COVENTRY HISTORIC LANDSCAPE CHARACTERISATION FINAL REPORT English Heritage Project Number 5927 First published by Coventry City Council 2013 Coventry City Council Place Directorate Development Management Civic Centre 4 Much Park Street Coventry CV1 2PY © Coventry City Council, 2013. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying or recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers. DOI no. 10.5284/1021108 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Coventry Historic Landscape Characterisation study was funded by English Heritage as part of a national programme and was carried out by the Conservation and Archaeology Team of Coventry City Council. Eloise Markwick as Project Officer compiled the database and undertook work on the Character Area profiles before leaving the post. Anna Wilson and Chris Patrick carried out the subsequent analysis of the data, completed the Character Area profiles and compiled the final report. Thanks are due to Ian George and Roger M Thomas of English Heritage who commissioned the project and provided advice throughout. Front cover images: Extract of Board of Health Map showing Broadgate in 1851 Extract of Ordnance Survey map showing Broadgate in 1951 Extract of aerial photograph showing Broadgate in 2010 CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Location and Context 1 1.3 Coventry HLC: Aims, Objectives and Access to the Dataset 3 2. Coventry’s Prehistory and History 4 2.1 Prehistory 4 2.2 The Early Medieval/Saxon Period 5 2.3 The Medieval Period (1066-1539) 6 2.4 The Post Medieval Period (1540-1836) 8 2.5 Mid to Late 19th Century and Beginning of the 20th Century (1837-1905) 10 2.6 The First Half of the 20th Century (1906-1955) 12 2.7 Second Half of the 20th Century (1955-present) 13 3. -

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control. -

Barby Hill Archaeological Project: G.W

Barby Hill Archaeological Project: G.W. Hatton Project Report, Year 2, 2012/3 Barby Hill Archaeological Project Interim Report for Second Year, 2012/2013 Table of Contents 1. Introduction.............................................................................................2 1.1 Site map, with field numbers .....................................................................2 1.2 Summary of new work ..............................................................................3 2. Presentation of results ..............................................................................5 2.1 Modern period..........................................................................................5 2.2 Medieval period...................................................................................... 11 2.3 Roman period ........................................................................................ 12 2.4 Iron Age................................................................................................ 15 3. Interpretation ........................................................................................ 23 3.1 Modern period........................................................................................ 23 3.2 Medieval period ..................................................................................... 23 3.3 Roman period ........................................................................................ 25 3.4 Iron Age............................................................................................... -

Research on Weather Conditions and Their Relationship to Crashes December 31, 2020 6

INVESTIGATION OF WEATHER CONDITIONS AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP TO CRASHES 1 Dr. Mark Anderson 2 Dr. Aemal J. Khattak 2 Muhammad Umer Farooq 1 John Cecava 3 Curtis Walker 1. Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences 2. Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering University of Nebraska-Lincoln Lincoln, NE 68583-0851 3. National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO Sponsored by Nebraska Department of Transportation and U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration December 31, 2020 TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. SPR-21 (20) M097 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Research on Weather conditions and their relationship to crashes December 31, 2020 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Dr. Mark Anderson, Dr. Aemal J. Khattak, Muhammad Umer Farooq, John 26-0514-0202-001 Cecava, Dr. Curtis Walker 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. University of Nebraska-Lincoln 2200 Vine Street, PO Box 830851 11. Contract or Grant No. Lincoln, NE 68583-0851 SPR-21 (20) M097 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Nebraska Department of Transportation NDOT Final Report 1500 Nebraska 2 Lincoln, NE 68502 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes Conducted in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. 16. Abstract The objectives of the research were to conduct a seasonal investigation of when winter weather conditions are a factor in crashes reported in Nebraska, to perform statistical analyses on Nebraska crash and meteorological data and identify weather conditions causing the significant safety concerns, and to investigate whether knowing the snowfall amount and/or storm intensity/severity could be a precursor to the number and severity of crashes. -

Westbury Road, Chapelfields, Coventry This Is a Fantastic Family Home with Further Potential for the New Owners to Put Their Stamp On

Westbury Road, Chapelfields Offers Over £280,000 Westbury Road, Chapelfields, Coventry This is a fantastic family home with further potential for the new owners to put their stamp on. The home benefits from a fantastic location just minutes from the city centre easy access the local bus routes and train lines. The property has a small courtyard style garden and plenty of indoor space for the whole family and for entertaining. Entrance hall Entering from the front gated driveway with parking for several cars. Living room 13'9" x 11'9" (4.2 x 3.6) Located to the front of the property with a large bay allowing lots of natural light Dining room 15'5" x 15'5" (4.7 x 4.7) A very large room with lots of natural light and hard wood floor, perfect for the whole family. Kitchen 11'9" x 9'2" (3.6 x 2.8) To the rear of the property with gas hob built in dishwasher and a small breakfast area. Ground floor bedroom 12'1" x 9'10" (3.7 x 3) accessed from the dining room this is a very versatile space depending how many bedrooms you need. Currently used as a fourth bedroom but would easily suit being an office or another reception room even a play room. Wet room three piece suite with open shower. Store room 19'8" x 13'1" (6 x 4) A huge space currently used as a store room but is again a versatile space. you could have a gym space, store space, office space, the options are endless. -

Queensland Avenue, Chapelfields, Coventry, West Midlands, CV5 8FE Asking Price £230,000

EPC Awaited Queensland Avenue, Chapelfields, Coventry, West Midlands, CV5 8FE Asking Price £230,000 This property has been converted to allow four rooms to rent Chapelfields, Coventry Buy to let investment opportunity ! This property is immaculate throughout with potential to extend if required. The property has been converted into four bedrooms, with plenty of space for each tenant. To the ground floor there are two reception rooms, both being used as bedrooms with one en suite, the large kitchen diner is very convenient. To the first the first floor there are two double bedrooms, family bathroom and a kitchen. To the rear there is a secure garden with a garage. If you are looking to rent to students or workers this is an excellent opportunity. Other benefits include gas central heating and double glazing. This property is not only for investors, it would be great for a family. To arrange a viewing please contact a member of the team. Viewing arrangement by appointment 024 7625 7321 [email protected] Bairstow Eves, 153 - 157 New Union Street, Coventry https://www.bairstoweves.co.uk Interested parties should satisfy themselves, by inspection or otherwise as to the accuracy of the description given and any floor plans shown in these property details. All measurements, distances and areas listed are approximate. Fixtures, fittings and other items are NOT included unless specified in these details. Please note that any services, heating systems, or appliances have not been tested and no warranty can be given or implied as to their working order. A member of Countrywide plc. -

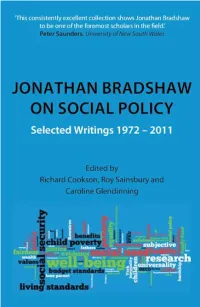

Jonathan Bradshaw on Social Policy Selected Writings 1972–2011

Jonathan Bradshaw on Social Policy Selected Writings 1972–2011 Jonathan Bradshaw on Social Policy Selected Writings 1972–2011 Edited by Richard Cookson, Roy Sainsbury and Caroline Glendinning © J R Bradshaw, R A Cookson, R Sainsbury and C Glendinning 2013 Copyright in the original versions of the essays in this book resides with the original publishers, as listed in the acknowledgements. Published by University of York. Edited by Richard Cookson, Roy Sainsbury and Caroline Glendinning. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, adapted, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the copyright holders. The rights of J R Bradshaw, R A Cookson, R Sainsbury and C Glendinning to be identified as the authors of this work have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-1-907265-22-8 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-907265-23-5 (epub) ISBN 978-1-907265-24-2 (mobi) Cover design by Richard Cookson and Clare Brayshaw Prepared and printed by: York Publishing Services Ltd 64 Hallfield Road Layerthorpe York YO31 7ZQ Tel: 01904 431213 Website: www.yps-publishing.co.uk Contents Notes on the editors Acknowledgements Introduction 1. The taxonomy of social need 1 2. Legalism and discretion 13 3. The family fund: an initiative in social policy 35 4. Energy and social policy 71 5. Evaluating adequacy: the potential of budget standards 81 6. Policy and the employment of lone parents in 20 countries 105 7. -

Welcome Landlord Forum

Landlord Newsletter May 2013 | Issue 1 www.warwickdc.gov.uk This newsletter is designed to keep Welcome ... to our new Warwick District Landlord Newsletter, private Landlords which we hope will keep you up to date with the latest informed of topical news and information. issues relating to We will issue newsletters electronically to all Landlords and Letting private letting. Agents who register their email address with the Private Sector Housing team at [email protected] The newsletter is produced by members of the Landlord Forum Steering Group. If you are interested in joining this Group, please email: [email protected]. IN THIS ISSUE: Regaining Possession: common mistakes Student Market Update Landlord Energy Efficiency Forum ECOs and EPCs The next Landlord Forum will take place: Tuesday 18 June | 6 - 8pm | Victoria House, Warwick Private 59 Willes Road, Leamington Spa, CV32 4PT. Leasing Scheme The agenda will include sessions on energy efficiency, Houses in Multiple fire safety, regaining possession, Article 4 Direction (HMO’s) Occupancy: Licensing and Private Sector Housing updates. and Accreditation There is no charge to attend. All we ask is that you pre-register Tips for Landlords by emailing: [email protected] or by calling: 01926 456733. Please also indicate if you wish to bring a guest when booking. Regaining Possession: Warwick District Council Private Sector Common Mistakes Lease Scheme It is little wonder that landlords often We are the only business in this country that has a serious as violent behaviour towards other people. The Council are working in partnership with misunderstand their legal position legal obligation to continue to provide our services Many landlords believe that if the tenant has been Chapter 1, a Registered Provider, who are when it comes to taking back (property) to customers (Tenants) for 8 weeks arrested by the Police he can be evicted from the operating a new lease scheme which will possession of their properties.. -

The London Gazette, £Th February 1976 2005

THE LONDON GAZETTE, £TH FEBRUARY 1976 2005 LAWFORD, Charles John, of 8, Chadleigh Court, Churchffl BURNLEY. No. of Matter—28 of 1975. Date of Order Road, Brackley, Northamptonshire lately residing at 54, —29th Jan., 1976. Date of Filing Petition—25th Sept., Sapley Road, Hartford, Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, 1975. Filling Station Manager, lately a SALES REPRESENTA- TIVE and formerly a MINI CAB DRIVER and COM- HAS SELL, Colin Michael, residing and lately carrying on PANY DIRECTOR. Court—BANBURY (by transfer business at " Cairns", North End, Exning, near New from High Court of Justice). No. of Matter—3lA of market in the county of Suffolk, RACEHORSE 1975. Date of Order—28th Jan., 1976. Date of Filing TRAINER. Court—CAMBRIDGE. No. of Matter—5. Petition—1st Sept., 1975. of 1976. Date of Order—2nd Feb., 1976. Date of Filing Petition—2nd Feb., 1976. HALL, Henry, residing and carrying on business at 11, Green Lane, Ellesmere Port, Merseyside as a GENERAL FINN, Francis Duncan, residing at 53, Albert Road, Deal, CONTRACTOR. Court—BIRKENHEAD. No. of Kent and previously at 72A, The Strand, Walmer, Deal Matter—4 of 1976. Date of Order—3rd Feb., 1976. and carrying on business at 67, Beach Street, Deal, under Date of Filing Petition—3rd Feb., 1976. the style of Duncan Finn's Fishing Tackle, FISHING TACKLE RETAILER. • Court—CANTERBURY. No. HOLFORD, Geoffrey Percy, residing at 16, Pearmans Croft, of Matter—11 of 1976. Date of Order—28th Jan., 1976. Hollywood, Birmingham, B47 5ER in the metropolitan Date of Filing Petition—28th Jan., 1976. county of West Midlands, and lately residing and carrying on business at 82, Institute Road, Kings Heath, Birming- MOUNT, George Michael Charles, unemployed, of Beven- ham, B14 7EY in the aforesaid county under the style den Oast, Great Chart, Ashford, Kent, formerly residing of "G. -

Investigation of Weather Conditions and Their Relationship to Crashes

INVESTIGATION OF WEATHER CONDITIONS AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP TO CRASHES Dr. Mark Anderson1 Dr. Aemal J. Khattak2 Muhammad Umer Farooq2 John Cecava1 Curtis Walker3 1. Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences 2. Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering University of Nebraska-Lincoln Lincoln, NE 68583-0851 3. National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO Sponsored by Nebraska Department of Transportation and U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration December 31, 2020 TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. SPR-21 (20) M097 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Research on Weather conditions and their relationship to crashes December 31, 2020 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Dr. Mark Anderson, Dr. Aemal J. Khattak, Muhammad Umer Farooq, John 26-0514-0202-001 Cecava, Dr. Curtis Walker 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. University of Nebraska-Lincoln 2200 Vine Street, PO Box 830851 11. Contract or Grant No. Lincoln, NE 68583-0851 SPR-21 (20) M097 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Nebraska Department of Transportation NDOT Final Report 1500 Nebraska 2 Lincoln, NE 68502 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes Conducted in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. 16. Abstract The objectives of the research were to conduct a seasonal investigation of when winter weather conditions are a factor in crashes reported in Nebraska, to perform statistical analyses on Nebraska crash and meteorological data and identify weather conditions causing the significant safety concerns, and to investigate whether knowing the snowfall amount and/or storm intensity/severity could be a precursor to the number and severity of crashes. -

River Nene Waterspace Study

River Nene Waterspace Study Northampton to Peterborough RICHARD GLEN RGA ASSOCIATES November 2016 ‘All rights reserved. Copyright Richard Glen Associates 2016’ Richard Glen Associates have prepared this report in accordance with the instructions of their clients, Environment Agency & the Nenescape Landscape Partnership, for their sole DQGVSHFL¿FXVH$Q\RWKHUSHUVRQVZKRXVHDQ\LQIRUPDWLRQFRQWDLQHGKHUHLQGRVRDW their own risk. River Nene Waterspace Study River Nene Waterspace Study Northampton to Peterborough On behalf of November 2016 Prepared by RICHARD GLEN RGA ASSOCIATES River Nene Waterspace Study Contents 1.0 Introduction 3.0 Strategic Context 1.1 Partners to the Study 1 3.1 Local Planning 7 3.7 Vision for Biodiversity in the Nene Valley, The Wildlife Trusts 2006 11 1.2 Aims of the Waterspace Study 1 3.1.1 North Northamptonshire Joint Core Strategy 2011-2031 7 3.8 River Nene Integrated Catchment 1.3 Key Objectives of the Study 1 3.1.2 West Northamptonshire Management Plan. June 2014 12 1.4 Study Area 1 Joint Core Strategy 8 3.9 The Nene Valley Strategic Plan. 1.5 Methodology 2 3.1.3 Peterborough City Council Local Plan River Nene Regional Park, 2010 13 1.6 Background Research & Site Survey 2 Preliminary Draft January 2016 9 3.10 Destination Nene Valley Strategy, 2013 14 1.7 Consultation with River Users, 3.2 Peterborough Long Term Transport 3.11 A Better Place for All: River Nene Waterway Providers & Local Communities 2 Strategy 2011 - 2026 & Plan, Environment Agency 2006 14 Local Transport Plan 2016 - 2021 9 1.8 Report 2 3.12 Peterborough