Lesson 6: Heavier Than Air—Rockets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weather and Aviation: How Does Weather Affect the Safety and Operations of Airports and Aviation, and How Does FAA Work to Manage Weather-Related Effects?

Kulesa 1 Weather and Aviation: How Does Weather Affect the Safety and Operations of Airports and Aviation, and How Does FAA Work to Manage Weather-related Effects? By Gloria Kulesa Weather Impacts On Aviation In addition, weather continues to play a significant role in a number of aviation Introduction accidents and incidents. While National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) reports ccording to FAA statistics, weather is most commonly find human error to be the the cause of approximately 70 percent direct accident cause, weather is a primary of the delays in the National Airspace contributing factor in 23 percent of all System (NAS). Figure 1 illustrates aviation accidents. The total weather impact that while weather delays declined with overall is an estimated national cost of $3 billion for NAS delays after September 11th, 2001, delays accident damage and injuries, delays, and have since returned to near-record levels. unexpected operating costs. 60000 50000 40000 30000 20000 10000 0 1 01 01 0 01 02 02 ul an 01 J ep an 02 J Mar May S Nov 01 J Mar May Weather Delays Other Delays Figure 1. Delay hours in the National Airspace System for January 2001 to July 2002. Delay hours peaked at 50,000 hours per month in August 2001, declined to less than 15,000 per month for the months following September 11, but exceeded 30,000 per month in the summer of 2002. Weather delays comprise the majority of delays in all seasons. The Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Transportation 2 Weather and Aviation: How Does Weather Affect the Safety and Operations of Airports and Aviation, and How Does FAA Work to Manage Weather-related Effects? Thunderstorms and Other Convective In-Flight Icing. -

Water Rocket Booklet

A guide to building and understanding the physics of Water Rockets Version 1.02 June 2007 Warning: Water Rocketeering is a potentially dangerous activity and individuals following the instructions herein do so at their own risk. Exclusion of liability: NPL Management Limited cannot exclude the risk of accident and, for this reason, hereby exclude, to the maximum extent permissible by law, any and all liability for loss, damage, or harm, howsoever arising. Contents WATER ROCKETS SECTION 1: WHAT IS A WATER ROCKET? 1 SECTION 3: LAUNCHERS 9 SECTION 4: OPTIMISING ROCKET DESIGN 15 SECTION 5: TESTING YOUR ROCKET 24 SECTION 6: PHYSICS OF A WATER ROCKET 29 SECTION 7: COMPUTER SIMULATION 32 SECTION 8: SAFETY 37 SECTION 9: USEFUL INFORMATION 38 SECTION 10: SOME INTERESTING DETAILS 40 Copyright and Reproduction Michael de Podesta hereby asserts his right to be identified as author of this booklet. The copyright of this booklet is owned by NPL. Michael de Podesta and NPL grant permission to reproduce the booklet in part or in whole for any not-for-profit educational activity, but you must acknowledge both the author and the copyright owner. Acknowledgements I began writing this guide to support people entering the NPL Water Rocket Competition. So the first acknowledgement has to be to Dr. Nick McCormick, who founded the competition many years ago and who is still the driving force behind the activity at NPL. Nick’s instinct for physics and fun has brought pleasure to thousands. The inspiration to actually begin writing this document instead of just saying that someone ought to do it, was provided by Andrew Hanson. -

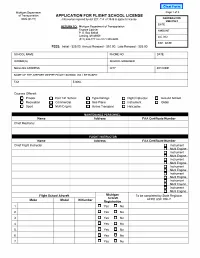

APPLICATION for FLIGHT SCHOOL LICENSE Page 1 of 2 of 4Transportation9 Informationrequired by Act 327, P.A

Michigan Department APPLICATION FOR FLIGHT SCHOOL LICENSE Page 1 of 2 of 4Transportation9 Informationrequired by Act 327, P.A. of 1945 to apply for license. AERONAUTICS 00 (01/21) USE ONLY RETURN TO: DATE Michigan Department of Transportation Finance Cashier AMOUNT P. 0. Box 30648 Lansing, Ml 48909 LIC.NO. (517) 242-7771 or (517) 335-9283 EXP.DATE FEES: Initial - $25.00, Annual Renewal - $10.00, Late Renewal - $25.00. SCHOOL NAME PHONE NO. DATE I OWNER(S) SCHOOL MANAGER MAILLING ADDRESS CITY I ZIP CODE NAME OF THE AIRPORT WHERE FLIGHT SCHOOL WILL BE BASED FAX I E-MAIL Courses Offered: □ Private □ Part 141 School □ Type Ratings D Flight Instructor D Ground School □ Recreation □ Commercial D Sea Plane D Instrument □ Glider □ Sport □ Multi Engine D Airline Transport D Helicopter MAINTENANCE PERSONNEL Name Address FAA Certificate Number Chief Mechanic INSTRUCTOR FLIGHT Name Address FAA Certificate Number Chief Flight Instructor □ Instrument □ Multi Enoine □ Instrument □ Multi Enqine □ Instrument □ Multi Engine □ Instrument □ Multi Enoine □ Instrument □ Multi Engine □ Instrument □ Multi Enoine □ Instrument □ Multi Enqine Flight School Aircraft Michigan To be completed by State Registrar Aircraft Make Model N Number AERO USE ONLY Registration 1. □ Yes □ No 2. □ Yes □ No 3. □ Yes □ No 4. □ Yes □ No 5. □ Yes □ No 6. □ Yes □ No 7. □ Yes □ No MDOT4009 (01/21) Page 2 of 2 Flight School Manager Compliance Checklist and Certification Please answer the questions below. Refer to the enclosed Michigan Aeronautics Code, section 259.85 (Flight Schools) requirements. Yes No Do You: □ □ Operate from an airport licensed by the State of Michigan? □ □ Have a written commercial operating agreement with the airport at which the school is based? (Submit a copy with this application or submit airport manager signature). -

Integrated Diagnostics of Rocket Flight Control

IEEE AEROSPACE CONFERENCE ¢ MARCH 2005, BIG SKY, MT Integrated Diagnostics of Rocket Flight Control Dimitry Gorinevsky¤, Sikandar Samary; Honeywell Labs, Fremont, CA 94539 John Bain, Honeywell Space Systems, Houston, TX 77058 and Gordon Aaseng, Honeywell Space Systems, Glendale, AZ 85308 Abstract— This paper describes an integrated approach to the approach by using simulated telemetry data for a launch parametric diagnostics demonstrated in a flight control sim- vehicle of Space Shuttle class. Faults seeded in the simula- ulation of a space launch vehicle. The proposed diagnostic tion are subsequently estimated by the VHM algorithms to approach is able to detect incipient faults despite the natural validate their performance. The estimated fault parameters masking properties of feedback in the guidance and control include air drag change from aerodynamic surface damage. loops. Estimation of time varying fault parameters uses para- This could model leading edge damage like that sustained metric vehicle-level data and detailed dynamical models. The in the Columbia Accident STS-107 mission. We also con- algorithms explicitly utilize the knowledge of fault mono- sider estimation and trending of such parameters as propul- tonicity (damage can only increase, never improve with time) sion performance, thrust vectoring actuator/gimbal wear, and where available. The developed algorithms can be applied a drift in one of GN&C sensors (pitch angle). These faults to health management of next generation space systems. We are choosen as plausible representative faults that demon- present a simulation case study of rocket ascent application strate the detection algorithm effectiveness. Development of to illustrate and validate the proposed approach. a practical VHM system would require an additional careful analysis and engineering of the fault models in the VHM al- TABLE OF CONTENTS gorithms. -

FAA Guide to Low Flying Aircraft

FAA Guide to Low-Flying Aircraft The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is the government agency responsible for aviation safety. We welcome information from citizens that will enable us to take corrective measures including legal enforcement action against individuals violating Federal Aviation Regulations (CFR). It is FAA policy to investigate citizen complaints of low-flying aircraft operated in violation of the CFR that might endanger persons or property. Remember that the FAA is a safety organization with legal enforcement responsibilities. We will need facts before we conduct an investigation. To save time, please have this information ready if you witness another low-flying aircraft. Please keep your notes: we may request a written statement. Here is the type of information we need: • Identification – Can you identify the aircraft? Was it military or civil? Was it a high or low wing aircraft? What was the color? Did you record the registration number which appears on the fuselage or tail? (On U.S. registered aircraft, that number will be preceded with a capital "N".) • Time and Place – Exactly when did the incident(s) occur? Where did this happen? What direction was the aircraft flying? • Altitude – How high or low was the aircraft flying? On what do you base your estimate? Was the aircraft level with or below the elevation of a prominent object such as a tower or building? Once we have the appropriate facts, personnel from the Flight Standards District Office (FSDO) will attempt to identify the offending aircraft operator. We can do this in several ways. For example, we can check aircraft flight records with our air traffic control information and/or sightings from other observers, such as local law enforcement officers. -

Oregon Department of Forestry Aviation Procedures Manual

2008 ODF Aviation Procedures Manual AVIATION PROCEDURES MANUAL 2008 EDITION OREGON DEPARTMENT OF FORESTRY AVIATION WORKING TEAM 1 2008 ODF Aviation Procedures Manual We should all bear one thing in mind when we talk about a colleague who “rode one in”. He called upon the sum of all his knowledge and made a judgment. He believed in it so strongly that he knowingly bet his life on it. That he was mistaken in his judgment is a tragedy, not stupidity. Every supervisor and contemporary Who ever spoke to him had an opportunity To influence his judgment, so a little bit of All of us goes in with every colleague we loose. “Author unknown” 2 2008 ODF Aviation Procedures Manual AVIATION RISK MANAGEMENT ASSESSMENT CHECKLIST • Is the Flight necessary? • Who is in-charge of the mission? • Are all hazards identified and have you made them known? • Should you stop the operation or flight due to change in conditions? - Communications? - Weather/turbulence? - Confusion? - Equipment? - Conflicting priorities? - Personnel? • Is there a better way to do it? • Are you driven by an overwhelming sense of urgency? • Can you justify your actions? • Are there other aircraft in the area? • Do you have an escape route? • Are there any rules broken? • Are communications getting tense? • Are you deviating from the assigned operation of flight? The twelve questions listed above should be applied to all aviation operations at all times. If you have any questions that cause you concern, it becomes your responsibility to discontinue the operation until you are confident that you can continue safely. Aviation safety is a personal responsibility. -

Techniques of Flight Instruction

Aviation Instructor's Handbook (FAA-H-8083-9) Chapter 9: Techniques of Flight Instruction Introduction Flight instructor Daniel decides his learner, Mary, has gained enough confidence and experience that it is time for her to develop personal weather minimums. While researching the subject at the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) website, he locates several sources that provide background information indicating that weather often poses some of the greatest risks to general aviation (GA) pilots, regardless of their experience level. He also finds charts and a lesson plan he can use. Daniel’s decision to help Mary develop personal weather minimums reflects a key component of the flight instructor’s job: providing the learner with the tools to ensure safety during a flight. What does “safety” really mean? How can a flight instructor ensure the safety of flight training activities, and also train clients to operate their aircraft safely after they leave the relatively protected flight training environment? According to one definition, safety is the freedom from conditions that can cause death, injury, or illness; damage to loss of equipment or property, or damage to the environment. FAA regulations are intended to promote safety by eliminating or mitigating conditions that can cause death, injury, or damage. These regulations are comprehensive but instructors recognize that even the strictest compliance with regulations may not guarantee safety. Rules and regulations are designed to address known or suspected conditions detrimental to safety, but there is always the possibility that a combination of hazardous circumstances will arise. The recognition of aviation training and flight operations as a system led to a “system approach” to aviation safety. -

Suborbital Flights and the Delimitation of Air Space Vis-À-Vis Outer Space: Functionalism, Spatialism and State Sovereignty

Reference: OOSA/2017/19 12 September 2017 CU 2017/351(D)/OOSA/CPLA Submitted to Office for Outer Space Affairs, United Nations Office at Vienna, P.O. Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria. ([email protected]) December 9, 2017 A Submission to the United Nations Office of Outer Space Affairs by The Space Safety Law & Regulation Committee of the International Association for the Advancement of Space Safety SUBORBITAL FLIGHTS AND THE DELIMITATION OF AIR SPACE VIS-À-VIS OUTER SPACE: FUNCTIONALISM, SPATIALISM AND STATE SOVEREIGNTY. Prepared by: Paul Stephen Dempsey and Maria Manoli . The authors would like to thank the IAASS Space Safety Law and Regulation Committee for reviewing earlier drafts of this submission, and in particular, John Bacon, Ram S. Jakhu, and Sa’id Mosteshar, Andy Quinn, and Tommaso Sgobba. Tomlinson Professor Emeritus of Global Governance in Air & Space Law, and Director Emeritus of the Institute of Air & Space Law, McGill University. ABJ, JD University of Georgia; LLM, George Washington University; DCL, McGill University. Doctoral candidate, Erin J. C. Arsenault Doctoral Fellow in Space Governance, and N. M. Matte Fellow, Institute of Air & Space Law, McGill University; Teaching Fellow, Faculty of Law, McGill University; Researcher, 2017 Centre for International Law and International Relations, Hague Academy of International Law. BCL, LLM, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens; LLM, Institute of Air & Space Law, McGill University. INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SPACE SAFETY Abstract: The paper examines the definition and delimitation of outer space and its relationship to air space, and proposes a remedy to the uncertainty created by the significant differences in the Air Law and Space Law regimes. -

Aircraft Technology Roadmap to 2050 | IATA

Aircraft Technology Roadmap to 2050 NOTICE DISCLAIMER. The information contained in this publication is subject to constant review in the light of changing government requirements and regulations. No subscriber or other reader should act on the basis of any such information without referring to applicable laws and regulations and/or without taking appropriate professional advice. Although every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, the International Air Transport Association shall not be held responsible for any loss or damage caused by errors, omissions, misprints or misinterpretation of the contents hereof. Furthermore, the International Air Transport Association expressly disclaims any and all liability to any person or entity, whether a purchaser of this publication or not, in respect of anything done or omitted, and the consequences of anything done or omitted, by any such person or entity in reliance on the contents of this publication. © International Air Transport Association. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, recast, reformatted or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission from: Senior Vice President Member & External Relations International Air Transport Association 33, Route de l’Aéroport 1215 Geneva 15 Airport Switzerland Table of Contents Table of Contents .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Space Exploration Word Search (In Your “Exploration,” Check for Words Spelled Backwards.)

Space Exploration Word Search (In your “exploration,” check for words spelled backwards.) G N O T L R Y U F S Y S L E A L P O N E T E L D R S A A M V L I B I I L I V C S T T U S F M W G V T G E O O X E E N R E B Y A H H A U S T R N L C A A Q R Y T T N T F C J A L H T R G L Q Y T T X S R O L I U S T R F U D N M W X R M P T E M H N F O Z N H T F S O E E A T J C W D I O R E T S A C R U T W N L I F T O F F D H S K S A E T M I V T M R T I B R O E C B Q G D O N O O M S Q O V A T E B L A S T L R Y T D P P N L H V A M R K M S J G F S Z K V X Find the following words: Asteroid Mars Station Blast Moon Telescope Countdown Orbit Earth Planets Flight Rocket Gravity Rover Launch Satellite Liftoff Space Light Stars Astronaut Scramble C O S M I C Z A E M L S U O D X M U E S E Z P O C K R T E I S A N S T E N A L P A U N W S A R E U B F Y Y P N L P V J C I S V E A H E M U P N C S E O Y G T W Q N O S O O Q Q B N V T R D E R I M W I O V I N U E G F U U R A S T R O N A U T R R A O C I O A A J S F E M P Y B J L S R R I U V A J C A E A E X U A O E P D Y T O Z N N G G N E L X I M F S U E A R T H Q E P K T Y R C S R A T S H Q L X N E F W F B G N T O H Z R E Y R D N X W M N K J N E F P Find the following words: Asteroids Journey Pluto Astronaut Jupiter Saturn Cosmic Mars Space Discovery Mercury Stars Earth Moon Sun Exploration Neptune Uranus Galaxy Planets Venus The Earth in 3-D Materials: Earth template – 1 sheet per Cub Scout Scissors Glue Markers/Crayons What do the people in space see when they are orbiting the earth? They see the earth! Instructions: 1. -

Where Is Space? and Why Does That Matter?

Space Traffic Management Conference 2014 Roadmap to the Stars Nov 5th, 3:15 PM Where is Space? And Why Does That Matter? Bhavya Lal Science and Technology Policy Institute, [email protected] Emily Nightingale Science and Technology Policy Institute, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/stm Part of the Aerospace Engineering Commons, and the Science and Technology Policy Commons Lal, Bhavya and Nightingale, Emily, "Where is Space? And Why Does That Matter?" (2014). Space Traffic Management Conference. 16. https://commons.erau.edu/stm/2014/wednesday/16 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Space Traffic Management Conference by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Where is Space? And Why Does That Matter? Bhavya Lal, Ph.D. Research Staff Member Emily Nightingale, Science Policy Fellow Science and Technology Policy Institute, 1899 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington DC 20006 Abstract Despite decades of debate on the topic, there is no consensus on what, precisely, constitutes the boundary between airspace and outer space. The topic is mired in legal and political conundrums, and the easy solution to-date has been to not agree on a definition of space. Lack of a definition, some experts claim, has not limited space-based activities, and therefore is not a hurdle that must be overcome. There are increasing calls however in light of increasing (and expectations of increasing) space traffic, both orbital and sub- orbital. This paper summarizes the proposed delimitation of space, the current debate on whether or not the boundary should be defined and internationally accepted, and our assessment on the need to define it based on emerging space traffic management needs. -

Aeronautics (AERN)

Kent State University Catalog 2021-2022 1 AERN 15745 NON-PILOT ELEMENTS OF FLIGHT THEORY 3 Credit AERONAUTICS (AERN) Hours Basic instruction in areas to include: Federal Regulations, navigation, AERN 12500 SURVEY OF AERONAUTICS 3 Credit Hours communication, airspace, weather, basic aerodynamics, and aero- This course provides an overview of the air transportation industry and medical factors which give the student a foundation in aeronautics. This gives students a broad overview of career requirements and opportunities course does not satisfy the Federal Aviation Regulation requirement for in several fields to include professional piloting, air traffic control and endorsement to take the Airman Knowledge Exam for a private pilot nor aviation management. Student will gain historical perspective while does it satisfy the Aircraft Dispatch minor. learning about emerging trends. Prerequisite: None. Prerequisite: None. Schedule Type: Lecture Schedule Type: Lecture Contact Hours: 3 lecture Contact Hours: 3 lecture Grade Mode: Standard Letter Grade Mode: Standard Letter AERN 22500 INTRODUCTION TO AVIATION MAINTENANCE AERN 15000 INTRODUCTION TO AERONAUTICS 3 Credit Hours MANAGEMENT 2 Credit Hours Introduction to aeronautical and aerospace technology, including Introduction to the day-to-day concepts used by an aviation maintenance historical development, underlying science and technical applications. manager. Course provides an overview of the different aspects that The past, present and future social, economic, technical and political go into managing human resources and overseeing the safe, legal and impact of aviation are also explored. efficient inspection, repair and return to service of aircraft when working Prerequisite: None. at a private maintenance repair organization (MRO), an airline, or a Schedule Type: Lecture fixed-base operator (FBO).