Chapter 1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism By Matthew W. Horton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Dr. Na’ilah Nasir, Chair Dr. Daniel Perlstein Dr. Keith Feldman Summer 2019 Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions Matthew W. Horton 2019 ABSTRACT Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism by Matthew W. Horton Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Na’ilah Nasir, Chair This dissertation is an intervention into Critical Whiteness Studies, an ‘additional movement’ to Ethnic Studies and Critical Race Theory. It systematically analyzes key contradictions in working against racism from a white subject positions under post-Civil Rights Movement liberal color-blind white hegemony and "Black Power" counter-hegemony through a critical assessment of two major competing projects in theory and practice: white anti-racism [Part 1] and New Abolitionism [Part 2]. I argue that while white anti-racism is eminently practical, its efforts to hegemonically rearticulate white are overly optimistic, tend toward renaturalizing whiteness, and are problematically dependent on collaboration with people of color. I further argue that while New Abolitionism has popularized and advanced an alternative approach to whiteness which understands whiteness as ‘nothing but oppressive and false’ and seeks to ‘abolish the white race’, its ultimately class-centered conceptualization of race and idealization of militant nonconformity has failed to realize effective practice. -

The Culture of Wikipedia

Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia Good Faith Collaboration The Culture of Wikipedia Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. Foreword by Lawrence Lessig The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Web edition, Copyright © 2011 by Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. CC-NC-SA 3.0 Purchase at Amazon.com | Barnes and Noble | IndieBound | MIT Press Wikipedia's style of collaborative production has been lauded, lambasted, and satirized. Despite unease over its implications for the character (and quality) of knowledge, Wikipedia has brought us closer than ever to a realization of the centuries-old Author Bio & Research Blog pursuit of a universal encyclopedia. Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia is a rich ethnographic portrayal of Wikipedia's historical roots, collaborative culture, and much debated legacy. Foreword Preface to the Web Edition Praise for Good Faith Collaboration Preface Extended Table of Contents "Reagle offers a compelling case that Wikipedia's most fascinating and unprecedented aspect isn't the encyclopedia itself — rather, it's the collaborative culture that underpins it: brawling, self-reflexive, funny, serious, and full-tilt committed to the 1. Nazis and Norms project, even if it means setting aside personal differences. Reagle's position as a scholar and a member of the community 2. The Pursuit of the Universal makes him uniquely situated to describe this culture." —Cory Doctorow , Boing Boing Encyclopedia "Reagle provides ample data regarding the everyday practices and cultural norms of the community which collaborates to 3. Good Faith Collaboration produce Wikipedia. His rich research and nuanced appreciation of the complexities of cultural digital media research are 4. The Puzzle of Openness well presented. -

Identitarian Movement

Identitarian movement The identitarian movement (otherwise known as Identitarianism) is a European and North American[2][3][4][5] white nationalist[5][6][7] movement originating in France. The identitarians began as a youth movement deriving from the French Nouvelle Droite (New Right) Génération Identitaire and the anti-Zionist and National Bolshevik Unité Radicale. Although initially the youth wing of the anti- immigration and nativist Bloc Identitaire, it has taken on its own identity and is largely classified as a separate entity altogether.[8] The movement is a part of the counter-jihad movement,[9] with many in it believing in the white genocide conspiracy theory.[10][11] It also supports the concept of a "Europe of 100 flags".[12] The movement has also been described as being a part of the global alt-right.[13][14][15] Lambda, the symbol of the Identitarian movement; intended to commemorate the Battle of Thermopylae[1] Contents Geography In Europe In North America Links to violence and neo-Nazism References Further reading External links Geography In Europe The main Identitarian youth movement is Génération identitaire in France, a youth wing of the Bloc identitaire party. In Sweden, identitarianism has been promoted by a now inactive organisation Nordiska förbundet which initiated the online encyclopedia Metapedia.[16] It then mobilised a number of "independent activist groups" similar to their French counterparts, among them Reaktion Östergötland and Identitet Väst, who performed a number of political actions, marked by a certain -

A Content Analysis of Persuasion Techniques Used on White Supremacist Websites

A Content Analysis of Persuasion Techniques Used on White Supremacist Websites Georgie Ann Weatherby, Ph.D. Gonzaga University Brian Scoggins Gonzaga University Criminal Justice Graduate I. INTRODUCTION The Internet has made it possible for people to access just about any information they could possibly want. Conversely, it has given organiza- tions a vehicle through which they can get their message out to a large audience. Hate groups have found the Internet particularly appealing, because they are able to get their uncensored message out to an unlimited number of people (ADL 2005). This is an issue that is not likely to go away. The Supreme Court has declared that the Internet is like a public square, and it is therefore unconstitutional for the government to censor websites (Reno et al. v. American Civil Liberties Union et al. 1997). Research into how hate groups use the Internet is necessary for several reasons. First, the Internet has the potential to reach more people than any other medium. Connected to that, there is no way to censor who views what, so it is unknown whom these groups are trying to target for membership. It is also important to learn what kinds of views these groups hold and what, if any, actions they are encouraging individuals to take. In addition, ongoing research is needed because both the Internet and the groups themselves are constantly changing. The research dealing with hate websites is sparse. The few studies that have been conducted have been content analyses of dozens of different hate sites. The findings indicate a wide variation in the types of sites, but the samples are so broad that no real patterns have emerged (Gerstenfeld, Grant, and Chiang 2003). -

Wahrheit Sagen, Teufel Jagen

Das Original in Englisch: Wahrheit sagen, Teufel jagen ISBN 978- 1 – 937787 – 29 – 5 Gerard Menuhin Copyright 2015: GERARD MENUHIN und THE BARNES REVIEW Veröffentlichung durch: THE BARNES REVIEW, P.O. Box 15877, Washington, D.C. 20003 Die amerikanische Originalausgabe erschien unter dem Titel „Tell the Truth & Shame the Devil“ 2015 THE BARNES REVIEW. >>>>bumibahagia.com<<<< Übersetzung aus dem Amerikanischen von Jürgen Graf. Die Wiedergabe von russischen Eigennamen erfolgte nach Duden-Transkription. HINWEIS: Diese PDF-Datei ist keine offizielle Veröffentlichung! Bitte unterstützen Sie den Autor und erwerben Sie das Originalbuch. Weitere Hinweise am Ende! „Ich mache das vom englischen Original auf Deutsch übersetzte Buch online zugänglich, da ich meine Botschaft dringendst verbreiten möchte und die deutsche gedruckte Fassung auf sich warten lässt. Die Seite bumi bahagia (indonesisch, glückliche Erde) scheint mir bestens dafür geeignet, da ich glaube, dass deren Betreiber Thom Ram die gleichen Hoffnungen für die Menschheit hegt wie ich.“ -Gerard Menuhin- Widmung: Für Deutschland. Für Deutsche, die es noch sein wollen. Für die Menschheit. Wahrheit sagen, Teufel jagen Wie ein alter kleiner Mann im karierten Hemd zum Autor sprach Autor: Gerard Menuhin „Trauer ist Wissen; jene, die am meisten wissen, müssen angesichts der verhängnisvollen Wahrheit am tiefsten trauern, denn der Baum der Erkenntnis ist nicht jener des Lebens.“ – Byron, „Manfred“ Inhalt: Kapitel I - Vereitelt: Der letzte verzweifelte Griff der Menschheit nach Freiheit Kapitel II - Identifiziert: Illumination oder die Diagnose der Finsternis Kapitel III - Ausgelöscht: Zivilisation Kapitel IV - Endstadium: Das kommunistische Vasallentum Kapitel I Vereitelt: Der letzte verzweifelte Griff der Menschheit nach Freiheit Dieser Hund ist ein Labrador. Er bellt nur selten und ist gutmütig, wie die meisten Labradore. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School THE

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School THE ORGANIZATIONAL LANDSCAPE OF WHITE SUPREMACY A Thesis in Sociology by Isaiah Gerber Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science December 2019 ii The thesis of Isaiah Gerber was reviewed and approved* by the following: Gary Adler Assistant Professor of Sociology Thesis Advisor John McCarthy Distinguished Professor of Sociology Charles Seguin Assistant Professor of Sociology and Social Data Analytics Jennifer Van Hook Roy C. Buck Professor of Sociology and Demography Director, Graduate Program in Sociology *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Little past research has examined how the partitioning of the white supremacist social movement industry (SMI) compares to other SMIs. This is in spite of evidence that organizations within this SMI may be unique in their deployment of protest tactics and willingness to utilize violence. Scholarly analysis of other SMIs indicates that identifying diversity in organizational characteristics like professionalization, membership, frames, and organizational strategies is useful for partitioning SMIs. By evaluating the white supremacist SMI in terms of these four organizational characteristics, this study finds substantial evidence that there are eight distinct organizational clusters operating within the white supremacist SMI, that this diversity is driven by deployed organizational strategies, and that this SMI is unique in its use of violence and willingness to deploy a merchandizing-based organizational strategy. These findings provide both an alternative framework through which to understand diversity in the SMI of white supremacy, as well as evidence that the SMI of white supremacy is distinct within the US social movement sector in its deployment of violence and the merchandizing organizational strategies. -

4 Annual Report on Black/Jewish Relations in the United States in 1999

4th Annual Report on Black/Jewish Relations in the United States in 1999 · Cooperation · Conflict · Human Interest · Shared Experiences Foreword by Hugh Price, President, The National Urban League Introduction by Rabbi Marc Schneier, President, The Foundation For Ethnic Understanding 1 The Foundation for Ethnic Understanding 1 East 93rd Street, Suite 1C, New York, New York 10128 Tel. (917) 492-2538 Fax (917) 492-2560 www.ffeu.org Rabbi Marc Schneier, President Joseph Papp, Founding Chairman Darwin N. Davis, Vice President Stephanie Shnay, Secretary Edward Yardeni, Treasurer Robert J. Cyruli, Counsel Lawrence D. Kopp, Executive Director Meredith A. Flug, Deputy Executive Director Dr. Philip Freedman, Director Of Research Tamika N. Edwards, Researcher The Foundation for Ethnic Understanding began in 1989 as a dream of Rabbi Marc Schneier and the late Joseph Papp committed to the belief that direct, face- to-face dialogue between ethnic communities is the most effective path towards the reduction of bigotry and the promotion of reconciliation and understanding. Research and publication of the 4th Annual Report on Black/Jewish Relations in the United States was made possible by a generous grant from Philip Morris Companies. 2 FOREWORD BY HUGH PRICE PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL URBAN LEAGUE I am honored to have once again been invited to provide a foreword for The Foundation for Ethnic Understanding's 4th Annual "Report on Black/Jewish Relations in the United States. Much has happened during 1999 and this year's comprehensive study certainly attests to that fact. I was extremely pleased to learn that a new category “Shared Experiences” has been added to the Report. -

1 Understanding the Zionist World Cons Piracy

1 Understanding The Zionist World Cons piracy Zionism is a Cultural Cancer that is Destroying White Nations! By Making Destructive Behavior Socially Acceptable The Zionists have emasculated our nation by destroying our pride in America‘s Christian history. Without a commonly held memory a nation ceases to exist as a cohesive unit. The Zionists have labeled America‘s Christian Founding Fathers as ―racists‖ and ―white slavers‖ while at the same time suppressing the fact that the Zionists fi- nanced and participated in the Black slave trade. The Zionists have promoted multicultura lis m, celebrating every culture, no matter how backward and barbaric, except for White Western European culture. The Zionists have dri- ven our Christian heritage from the public square through the efforts of the ADL and the ACLU Lobby Groups. American children will grow up in a society wiped clean of any vestiges of the Bible, Christ or the Cross. However, the Menorah is still allowed in public displays and in the White House for Hannukah celebrations. The Zionists have torn our borders wide open, permitting, indeed cheering, the Third World immigrants who will soon replace the White Christian American majority. The Jacob Javits‘s and the Lautenbergs have designed legislation that will, in the not too distant future, eventually genocide the White Race of people. They have done all this while simultaneously supporting a Zionist-only State in the Middle East. The Zionists have pushed, created and profited from pornography and perverse entertainment. The Zionists make up 90% of all American pornog- raphers. The Hollywood they run has mainstreamed wife-swapping, common law marriages, fornication, homo- sexuality, lesbianism, transvestitism, pedophilia, drug and alcohol abuse and self-indulgence. -

DEALING with DEMENTIA Mcdowell Holds As Rates Rise, More Families Struggle with Decline of Loved Ones, H&F 1 Partly Cloudy

74 / 49 U.S. OPEN DEALING WITH DEMENTIA McDowell holds As rates rise, more families struggle with decline of loved ones, H&F 1 Partly cloudy. on for the win H&F 12 DRILL TO KILL OIL SPILL >>> Far offshore, crews drill into Gulf to stop the gushing well, MAIN 6 MONDAY 75 CENTS June 21, 2010 TIMES-NEWS Magicvalley.com “I had nightmares for years. It happened 15 years ago. We were going through a crossing, and a car ran through right in front of us. We broadsided him completely. The young man was killed. I can still see it every time I close my eyes.” — Steve Roberts, railroad conductor from Pocatello DREW GODLESKI/For the Times-News Linda Devaney sits away from the crowd at the Twin Falls City Park during the Art in the Park festival Saturday. The Twin Falls City Council will hear a proposal Monday to ban smoking in city parks. While Devaney recognizes the risks of second-hand smoke, she still believes ‘The government shouldn’t legislate morality.’ Smoke-free park proposal tops council agenda not scheduled for action — City also to look is complete with ban-sup- porting numbers from an ASHLEY SMITH/Times-News at $8.5M-plus in online survey. It will be Shoshone Police Chief Jon Daubner, right, talks with train engineer Mike Stinson, center, and officer Bradley Germann on Friday while riding a pushed by the Magic Valley Union Pacific train that was taking part in a railroad-safety awareness ride from Shoshone to Gooding. project awards Tobacco-Free Youth Coalition, said Elvia By Nick Coltrain Caldera, health education Times-News writer specialist for the health dis- trict. -

The North American White Supremacist Movement: an Analysis Ofinternet Hate Web Sites

wmTE SUPREMACIST HATE ON THE WORLD WIDE WEB "WWW.HATE.ORG" THE NORTH AMERICAN WIDTE SUPREMACIST MOVEMENT: AN ANALYSIS OF INTERNET HATE WEB SITES By ALLISON M. JONES, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School ofGraduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment ofthe Requirements for the Degree Master ofArts McMaster University © Copyright by Allison M. Jones, October 1999 MASTER OF ARTS (1999) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (Sociology) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: "www.hate.org" -- The North American White Supremacist Movement: An Analysis ofInternet Hate Web Sites AUTHOR: Allison M. Jones, B.A. (York University) SUPERVISOR: Professor V. Satzewich NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 220 ii Abstract This thesis is a qualitative study ofNorth American white supremacist organisations, and their Internet web sites. Major issues framing the discussion include identity and racism. The thesis takes into consideration Goffman's concepts of'impression management' and 'presentation ofself as they relate to the web site manifestations of 'white power' groups. The purpose ofthe study is to analyse how a sample ofwhite supremacist groups present themselves and their ideologies in the context ofthe World Wide Web, and what elements they use as a part oftheir 'performances', including text, phraseology, and images. Presentation ofselfintersects with racism in that many modern white supremacists use aspects ofthe 'new racism', 'coded language' and'rearticulation' in the attempt to make their fundamentally racist worldview more palatable to the mainstream. Impression management techniques are employed in a complex manner, in either a 'positive' or 'negative' sense. Used positively, methods may be employed to impress the audience with the 'rationality' ofthe arguments and ideas put forth by the web site creators. -

The Easton Family of Southeast Massachusetts: the Dynamics Surrounding Five Generations of Human Rights Activism 1753--1935

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2006 The Easton family of southeast Massachusetts: The dynamics surrounding five generations of human rights activism 1753--1935 George R. Price The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Price, George R., "The Easton family of southeast Massachusetts: The dynamics surrounding five generations of human rights activism 1753--1935" (2006). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 9598. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/9598 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission ___________ Author's Signature: Date: 7 — 2 ~ (p ~ O b Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

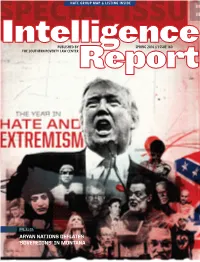

Aryan Nations Deflates

HATE GROUP MAP & LISTING INSIDE PUBLISHED BY SPRING 2016 // ISSUE 160 THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER PLUS: ARYAN NATIONS DEFLATES ‘SOVEREIGNS’ IN MONTANA EDITORIAL A Year of Living Dangerously BY MARK POTOK Anyone who read the newspapers last year knows that suicide and drug overdose deaths are way up, less edu- 2015 saw some horrific political violence. A white suprem- cated workers increasingly are finding it difficult to earn acist murdered nine black churchgoers in Charleston, S.C. a living, and income inequality is at near historic lev- Islamist radicals killed four U.S. Marines in Chattanooga, els. Of course, all that and more is true for most racial Tenn., and 14 people in San Bernardino, Calif. An anti- minorities, but the pressures on whites who have his- abortion extremist shot three people to torically been more privileged is fueling real fury. death at a Planned Parenthood clinic in It was in this milieu that the number of groups on Colorado Springs, Colo. the radical right grew last year, according to the latest But not many understand just how count by the Southern Poverty Law Center. The num- bad it really was. bers of hate and of antigovernment “Patriot” groups Here are some of the lesser-known were both up by about 14% over 2014, for a new total political cases that cropped up: A West of 1,890 groups. While most categories of hate groups Virginia man was arrested for allegedly declined, there were significant increases among Klan plotting to attack a courthouse and mur- groups, which were energized by the battle over the der first responders; a Missourian was Confederate battle flag, and racist black separatist accused of planning to murder police officers; a former groups, which grew largely because of highly publicized Congressional candidate in Tennessee allegedly conspired incidents of police shootings of black men.