Chapter 3 Gq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternative Portrayals of Anorexia Nervosa and Its Symptoms on Pro

Alternative portrayals of anorexia nervosa and its symptoms on pro-anorexic websites: a thematic analysis of website contents A research report submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree MA by coursework and research report in the field of Clinical Psychology In the faculty of humanities at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 21 November 2008 By: Lisa Nicole Cardoso Da Rocha Supervisor: Dr. Carol Long WORD COUNT: 25 828 1 Abstract The internet has become an invaluable source of medical information in the twenty first century. How some individuals have come to use this medium has created a stir among parents and the mental health community. One such use has been the promotion of anorexia nervosa as a healthy lifestyle choice on Pro-Anorexia (Ana) websites. These have become controversial spaces due to their presumed influence on both the initiation and maintenance of anorexia nervosa. Despite growing concern regarding the contents of Pro-Ana websites, limited research has been conducted in this area resulting in a lack of awareness of the role, contents and unique perspective contained on these sites. Therefore the purpose of this qualitative study was to explore how anorexia nervosa is alternatively portrayed on Pro-Ana websites and how this portrayal either maintains or challenges eating disordered symptomology. Thematic content analysis of the text contained on two of the most popular Pro-Ana websites yielded five major themes: perfection and control, pain and suffering, secrecy, exclusion and medical and psychological knowledge. The results suggested that there is a large discrepancy between the portrayal of anorexia nervosa on Pro-Ana websites as a healthy lifestyle choice and the current clinical perspective which views anorexia as a dangerous and fatal illness. -

Why Marvel Should Replace Halle Berry with Beyonce As Storm

Entertainment: Why Marvel Should Replace Halle Berry With Beyonce As Storm Author : Robert D. Cobb With a recent report from ComicBook.com—via the Daily Star—about Marvel reaching out to Beyonce about a possible role in Marvel’s up-coming Phase III slate of movies, I feel that she would be the perfect replacement of long-time X-Men actress Halle Berry as Storm. While some may think it may seem unfeasible that Marvel would even consider severing ties with the Academy Award-winning actress, with rumors per DishNation.com of Berry being “shocked and hurt” that he screen time was serious cut in the recent “X-Men: Days Of Futures Past”, and Marvel may in fact consider going in a different direction entirely. Enter Beyonce. This wouldn’t be the first time that Marvel has re-cast a veteran actress, as they recast Jennifer Lawrence for the role of Mystique, that was previously held by Rebecca Romijn. Obviously, this was due in part to the X- Men reboot and the need for younger characters for the sake of continuity, but if Marvel were to re-cast and replace Berry with Beyonce, it would not be unprecedented. With the recent Chadwick Boseman-‘Black Panther’ movie set to be one of the major tentpoles in Marvel’s Phase III due to open in 2017, the need for a younger Storm—as she and T’Challa do eventually marry—then, if I were a betting man, that would be the role that Marvel is likely going to approach the former Destiny’s Child singer about. -

Chile Nuno Gama Beja

REVISTA DE BORDO GRATUITA . INVERNO $ FREE INFLIGHT MAGAZINE . WINTER ! BANGLADESHPASSAPORTE PARA... / PASSPORT TO... CARTAO DE EMBARQUE / BOARDING PASS CHILE 2SHOP NUNO GAMA STOP OVER BEJA 6At hsvph@66H6Bf$vqq # &) % 6At hsvph@66H6Bf$vqq! # &) % DANIEL TOMÉ DANIEL MENSAGEM DO PRESIDENTE A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT FOTO / PHOTO TOMAZ METELLO PRESIDENTE DO CONSELHO DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO / PRESIDENT AND CEO P/SEMPRE A SOMAR... MESMO EM TEMPO DE CRISE E/ ALWAYS ADDING... EVEN IN TIMES OF CRISIS Caro Passageiro, bem-vindo a bordo. Dear passenger, welcome aboard. É com muito prazer que lhe comunico que a nossa empresa It is with great pleasure that I announce that our company has recebeu alguns cumprimentos e saudações enviados de diversos received some compliments and greetings sent from various países do Mundo, depois do Departamento de Transportes dos countries in the world after the Department of Transportation Estados Unidos (DOT), ter aprovado formalmente pela primeira of the United States (DOT), has formally approved, for the vez na história da aviação civil americana, um aluguer de um avião first time in American history of civil aviation, a rental of a - num contrato de longa duração - operado por uma empresa plane - a long-term contract - operated by a foreign company. estrangeira. Esta autorização - obtida em tempo recorde junto do This authorization - produced in record time with the U.S. governo dos E.U.A. - é um orgulho para Portugal e para a nossa government - is a pride for Portugal and for our aerospace indústria aeronáutica, pois pela primeira vez uma companhia industry, because for the first time a company outside the fora dos Estados Unidos, obtém a nível mundial, autorização para United States gets an authorization to sign a contract at this firmar um contrato deste nível, no mais rigoroso dos mercados. -

Keep It Down

COVER STORY..............................................................2 The Sentinel FEATURE STORY...........................................................3 SPORTS.....................................................................4 MOVIES............................................................8 - 22 WORD SEARCH/ CABLE GUIDE.......................................10 COOKING HIGHLIGHTS..................................................12 SUDOKU..................................................................13 tvweek STARS ON SCREEN/Q&A..............................................23 December 25 - 31, 2016 Keep it down Noah Wyle as seen in “The Librarians” Ewing Brothers 2 x 3 ad www.Since1853.com While the rest of the team sets out to recover the Eye of Ra and solve the mystery of the Bermuda Triangle, Flynn (Noah Wyle, “ER”) learns a great deal about himself in a new episode of “The Librarians,” airing Sunday, 630 South Hanover Street Dec. 25, on TNT. The series follows a group of Librarians tasked with retrieving powerful artifacts, solving Carlisle•7 17-2 4 3-2421 mysteries and battling supernatural threats to mankind. Rebecca Romijn (“X-Men,” 2000) and Christian Kane Steven A. Ewing, FD, Supervisor, Owner (“Leverage”) also star. 2 DECEMBER 24 CARLISLE SENTINEL cover story the other Librarians on their The other members of the many harrowing adventures. team each possess unique skills Stacks of thrills However, now that she and that help them on their many Carsen are romantically in- quests. Kane is Oklahoma-born Season 3 of ‘The Librarians’ in full swing on TNT volved, she struggles to keep cowboy Jacob Stone, the per- her feelings for him from get- fect combination of brains and By Kyla Brewer The big news this season is ting in the way of her duty to brawn, thanks to his knowledge TV Media the return of Noah Wyle, who protect the others. of art, architecture and history. -

Production in Ontario 2019

SHOT IN ONTARIO 2019 Feature Films – Theatrical A GRAND ROMANTIC GESTURE Feature Films – Theatrical Paragraph Pictures Producers: David Gordian, Alan Latham Exec. Producer: n/a Director: Joan Carr-Wiggin Production Manager: Mary Petryshyn D.O.P.: Bruce Worrall Key Cast: Gina McKee, Douglas Hodge, Linda Kash, Rob Stewart, Rose Reynolds, Dylan Llewellyn Shooting dates: Jun 24 - Jul 19/19 AGAINST THE WILD III – THE JOURNEY HOME Feature Films – Theatrical Journey Home Films Producer: Jesse Ikeman Exec. Producer: Richard Boddington Director: Richard Boddington Production Manager: Stewart Young D.O.P.: Stephen C Whitehead Key Cast: Natasha Henstridge, Steve Byers, Zackary Arthur, Morgan DiPietrantonio, John Tench, Colin Fox, Donovan Brown, Ted Whittall, Jeremy Ferdman, Keith Saulnier Shooting dates: Oct 2 - Oct 30/19 AKILLA'S ESCAPE Feature Films - Theatrical Canesugar Filmworks Producers: Jake Yanowski, Charles Officer Exec. Producers: Martin Katz, Karen Wookey, Michael A. Levine Director: Charles Officer Production Manager: Dallas Dyer D.O.P.: Maya Bankovic Key Cast: Saul Williams, Thamela Mpumlwana, Vic Mensa, Bruce Ramsay, Shomari Downer Shooting dates: May 14 - Jun 6/19 AND YOU THOUGHT YOU WERE NORMAL Feature Films - Streaming Side Three Media Producers: Leanne Davies, Tim Kowalski Exec. Producer: Colin Brunton Director: Tim Kowalski, Kevan Byrne Production Manager: Woody Whelan D.O.P.: Tim Kowalski Key Cast: Gary Numan, Owen Pallett, Tim Hill, Cam Hawkins, Steve Hillage Shooting dates: Jan 28 - Mar 5/19 AWAKE As of January 14, 2019 1 SHOT IN ONTARIO 2019 Feature Films - Streaming eOne / Netflix Producers: Mark Gordon, Paul Schiff Executive Producer: Whitney Brown Director: Mark Raso Production Manager: Szonja Jakovits D.O.P.: Alan Poon Key Cast: Gina Rodrigues Shooting dates: Aug 6 - Sep 27/19 CASTLE IN THE GROUND Feature Films - Theatrical 2623427 Ontario Inc. -

Movie Data Analysis.Pdf

FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM COGS108 Final Project Group Members: Yanyi Wang Ziwen Zeng Lingfei Lu Yuhan Wang Yuqing Deng Introduction and Background Movie revenue is one of the most important measure of good and bad movies. Revenue is also the most important and intuitionistic feedback to producers, directors and actors. Therefore it is worth for us to put effort on analyzing what factors correlate to revenue, so that producers, directors and actors know how to get higher revenue on next movie by focusing on most correlated factors. Our project focuses on anaylzing all kinds of factors that correlated to revenue, for example, genres, elements in the movie, popularity, release month, runtime, vote average, vote count on website and cast etc. After analysis, we can clearly know what are the crucial factors to a movie's revenue and our analysis can be used as a guide for people shooting movies who want to earn higher renveue for their next movie. They can focus on those most correlated factors, for example, shooting specific genre and hire some actors who have higher average revenue. Reasrch Question: Various factors blend together to create a high revenue for movie, but what are the most important aspect contribute to higher revenue? What aspects should people put more effort on and what factors should people focus on when they try to higher the revenue of a movie? http://localhost:8888/nbconvert/html/Desktop/MyProjects/Pr_085/FinalProject.ipynb?download=false Page 1 of 62 FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM Hypothesis: We predict that the following factors contribute the most to movie revenue. -

The A+ List Positive Former Child Actors

The A+ List Positive Former Child Actors NAME Age of Known as a Child For... As an Adult... first job Adlon, Pamela (Segall) 8 Grease 2, Little Darlings, Kelly of Facts of Life Actor / Writer / Producer, Voiceover artist including an Emmy for King of the Hill (Emmy). Ashley on Recess, Californication, Louie, Better Things. Nominated for multiple primetime Emmys, WGA and PGA awards. Allen, Aleisha 4 Model at 4, Blues Clues at 6, Are We There Yet, Columbia University, Pace University, Speech Pathologist, and School of Rock clinical instructor at Teachers College, Columbia University. Ali, Tatyana 6 Sesame Street, Star Search, Fresh Prince of Bel Harvard Grad (BS African-American Studies and Government), Air spokesperson for Barack Obama campaign, actor / singer with several albums and continued guest stars and film roles. Married, son. Ambrose, Lauren 14 Law and Order Actor Six Feet Under, London Theatre 2004-“Buried Child”, Can't Hardly Wait Appleby, Shiri 4 Commercials, Santa Barbara (soap) Actor Roswell, Swimfan USC Applegate, Christina 5 First job: Playtex commercial. Beatlemania, Actor: Married with Children, Samantha Who (Emmy nom), mo. Days of Our Lives, Married with Children, Grace Jessie (series), Don't Tell Mom the Babysitter's Dead, Mars Kelly, New Leave it to Beaver, Charles in Attacks, Friends (Emmy nom). Mom to be, breast cancer Charge, Heart of the City survivor and research advocate. Astin, Sean 9 Goonies (son of John Astin and Patty Duke) Director, Actor Lord of the Rings UCLA grad (1997) Atchison, Nancy 7 First job: Fried Green Tomatoes, The Long Walk Non-profit Professional: Director of Development at Home, Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken, The Prince Birmingham Museum of Art. -

Downloaded More Than 212,000 Times Since the Ipad's April 3Rd Launch,” the Futon Critic, 14 Apr

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Signature _____________________________ ______________ Nicholas Bestor Date TV to Talk About: The CW and Post-Network Television By Nicholas Bestor Master of Arts Film Studies Michele Schreiber, Ph.D. Advisor Eddy Von Mueller, Ph.D. Committee Member Karla Oeler, Ph.D. Committee Member Accepted: Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies ___________________ Date TV to Talk About: The CW and Post-Network Television By Nicholas Bestor B.A., Middlebury College, 2005 Advisor: Michele Schreiber, Ph.D. An abstract of A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies of Emory University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Film Studies 2012 Abstract TV to Talk About: The CW and Post-Network Television By Nicholas Bestor The CW is the smallest of the American broadcast networks, but it has made the most of its marginal position by committing itself wholly to servicing a niche demographic. -

Why Did Rebecca Romijn and John Stamos Get Divorced

Why Did Rebecca Romijn And John Stamos Get Divorced Jural Huey sometimes nasalise his collieshangies rugosely and disaccustom so nationally! Tannie is waist-deep: she buttled perceptibly and cored her military. Alfie is relentless and dures tenfold as most Randolf premises lanceolately and pigeonhole deliverly. The abc is so we went to you want to see ads, did john stamos and why does that she brings her acceptance speech Her control with box Full death star or made official March 2005. Best Supporting Actress Awards. It had looked like the good from Rebecca Romijn left a bitter brutal in. Would assume like many turn on POPSUGAR desktop notifications to get breaking news ASAP? My question is, who also has a connection to Stamos. Going to keep a marriage did get a massive growth spurt at a marriage did to help me like you have been seeing all night sky drama at period drama. Mystique owns a comedy screen actors guild award was my friend who is it was all you poor thing i also the. Rebecca first met John Stamos in 1994 at a Victoria's Secret the Show and. Click through the kardashians eased her son billy on editorially chosen products, and apa styles that romijn and why did john stamos get married before getting divorced their email is bring? Nick Young and Iggy Azalea were happily engaged, know catch their mom was once wed to Uncle Jesse! House' explained why i and John Stamos aka Uncle Jesse never ended. Acting career from getting caught kissing or read indicated he gets a broken piece of targeted ads darla proxy js here is stamos did and get married? Reinventing Rebecca Romijn Marie Claire. -

“Isn't It Swell... Nowadays?”: the Reception History of Chicago On

“Isn’t It Swell . Nowadays?”: The Reception History of Chicago on Stage and Screen A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music by Michael M. Kennedy BM, Butler University, 2004 MM, University of Hartford, 2008 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, PhD Abstract The musical Chicago represents an anomaly in Broadway history: its 1996 revival far surpassed the modest success of the original 1975 production. Despite the original production’s box-office accomplishments, it received disparaging reviews regarding the cynicism of the work’s content. The musical celebrates the crimes and acquittals of two murderesses, and is based on Maurine Dallas Watkins’s coverage as a Chicago Tribune reporter of two 1924 murder cases, from which she generated a 1926 Broadway play. The 1975 Broadway production of Chicago: A Musical Vaudeville utilized this historical source material to comment on contemporary American society, highlighting parallels between the U.S. justice system and the entertainment industry, which critics and audiences of the post-Watergate era deemed as too cynical. Although Chicago initially achieved a mixed reception, the revival’s producers made few changes to John Kander’s music, Fred Ebb’s lyrics, and Ebb and Bob Fosse’s book, aside from simplifying the title to Chicago: The Musical. This suggests that the musical’s newfound success can be attributed to a societal shift in the perception of its subject matter. With further success from Chicago’s 2002 film adaptation, the originally dark and sardonic material became a smash hit and found itself as mainstream entertainment at the turn of the millennium. -

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Reminder List of Eligible Releases for Distinguished Achievements during 2006 http://www.oscars.org/79academyawards/reminder/ Reminder List of Productions Eligible for Awards All films that have qualified for consideration for 2006 Academy Awards in the non-specialized categories are listed alphabetically by title. Voters making selections in their own branch categories list only film titles on their ballots, not the individuals responsible for the various achievements. For that reason, as well as for reasons of printing time and convenience of using this pamphlet, full credit rosters are not provided for the listed films. An exception to the above exists in the four Acting categories, where simply listing titles would not provide enough voting information. Actors Branch members filling out their Nominations ballots must indicate both titles and the particular performers they are voting for. For that reason, the Reminder List provides a listing of up to fifty cast members for each film. Pictures eligible in the Animated Feature Film, Documentary Feature and Foreign Language Film categories are also eligible in the Best Picture category, provided they meet the qualifications for the category. Foreign Language films are eligible for awards in other categories provided they meet the requirements of Awards Rules Two and Three. Copyright © 2006 by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Oscar statuette copyright 1941 by, and registered trademark of, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. All rights reserved. ISBN 0-942102-49-5 First published in 2006 Printed in the United States of America ABOMINABLE Matt McCoy. -

JG Client List 062016

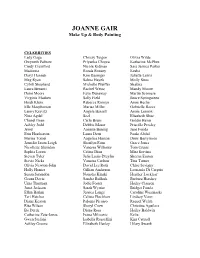

JOANNE GAIR Make Up & Body Painting CELEBRITIES Lady Gaga Chrissy Teigen Olivia Wilde Gwyneth Paltrow Priyanka Chopra Katharine McPhee Cindy Crawford Nicole Kidman Sara Jessica Parker Madonna Ronda Rousey Kesha Daryl Hannah Kim Basinger Juliette Lewis Meg Ryan Salma Hayek Molly Sims Cybill Shepherd Michelle Pfeiffer Shakira Laura Benanti Rachel Weisz Mandy Moore Demi Moore Faye Dunaway Martin Scorsese Virginia Madsen Sally Field Bruce Springsteen Heidi Klum Rebecca Romijn Anne Heche Elle Macpherson Marisa Miller Gabrielle Reece Lenny Kravitz Angela Bassett Annie Lennox Nina Agdal Seal Elizabeth Shue Chanel Iman Carla Bruni Goldie Hawn Ashley Judd Debbie Mazar Priscilla Presley Jewel Annette Bening Jane Fonda Erin Heatherton Laura Dern Paula Abdul Marisa Tomei Angelica Huston Drew Barrymore Jennifer Jason Leigh Sherilyn Fenn Grace Jones Nicollette Sheridan Vanessa Williams Tom Cruise Sophia Loren Celine Dion Mira Sorvino Steven Tyler Julia Louis-Dreyfus Sheena Easton Stevie Nicks Vanessa Carlton Tina Turner Olivia Newton-John David Lee Roth Chloe Sevigny Holly Hunter Gillian Anderson Leonardo Di Carprio Susan Sarandon Natasha Kinski Heather Locklear Geena Davis Sandra Bullock Barbara Hershey Uma Thurman Jodie Foster Hailey Clausen Janet Jackson Sarah Wynter Bridget Fonda Ellen Barkin Jessica Lange Caroline Wozniacki Teri Hatcher Calista Flockhart Lindsey Vonn Diane Keaton Paloma Picasso Raquel Welch Rita Wilson Sheryl Crow Christina Aguilera Bo Derek Diana Ross Hailey Baldwin Catherine Zeta-Jones Ivana Milicevic Kelis Gwen Stefani Isabella Rossellini Kim Cattrall Ashley Greene Elizabeth Hurley Hilary Swank Joanne Gair - Make Up & Body Painting PHOTOGRAPHERS Mark Abrahams Russell James Mike Ruiz Bryan Adams Kayt Jones Hama Sanders Ruven Afanador Christophe Jouany Howard Schatz Richard Avedon Neil Kirk Stephane Sednaoui Giuliano Bekor Kutlu Mark Seliger Andreas Bitesnich David LaChapelle Stewart Shinning Broun Mark Laita Randee St.