Israel's Partial Constitution: the Basic Laws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israeli Politics Rutgers University – New Brunswick Department of Political Science Fridays 11:30Am – 2:30Pm Scott Hall Room 206

Israeli Politics Rutgers University – New Brunswick Department of Political Science Fridays 11:30am – 2:30pm Scott Hall Room 206 Instructor: Geoffrey Levin Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Fridays, Upon Request Course Description: In proportion to its size, Israel is perhaps the most discussed and debated country in the world. Yet despite the global focus on Israel, few onlookers actually have a strong understanding of Israel’s complex and fragmented political system. This course will help you gain such an understanding by introducing you to the many political institutions, ideological visions, and demographic divisions that have driven Israeli politics from 1948 through the present day. While the course will familiarize you with many of the specifics of Israel – a Jewish state located in the Middle East – it also aims to give you a broader understanding of politics and how political institutions operate. Politics is, in a basic sense, the interaction between people and governing institutions. As a result, a considerable focus will be on the political institutions and peoples of modern Israel. Institutions include state organs such as the Knesset (the Israeli parliament), the judiciary, the premiership, and the military, as well as intermediaries such as political parties and the ideologies that guide them. You will also learn about the many ways people in Israel define themselves – Druze Arabs, the ultra-Orthodox (Haredim), Palestinian Christian citizens of Israel, Ethiopian Jews, Religious Zionist Jewish settlers, African asylum seekers, Ashkenazi Jews, Mizrahi/Sephardic Jews, LGBT Israelis, Israeli Arab Muslims, and others, with a focus on how these groups identify politically and how they interact with the Israeli political system. -

Palestinian Refugees: Adiscussion ·Paper

Palestinian Refugees: ADiscussion ·Paper Prepared by Dr. Jan Abu Shakrah for The Middle East Program/ Peacebuilding Unit American Friends Service Committee l ! ) I I I ' I I I I I : Contents Preface ................................................................................................... Prologue.................................................................................................. 1 Introduction . .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 The Creation of the Palestinian Refugee Problem .. .. .. .. .. 3 • Identifying Palestinian Refugees • Counting Palestinian Refugees • Current Location and Living Conditions of the Refugees Principles: The International Legal Framework .... .. ... .. .. ..... .. .. ....... ........... 9 • United Nations Resolutions Specific to Palestinian Refugees • Special Status of Palestinian Refugees in International Law • Challenges to the International Legal Framework Proposals for Resolution of the Refugee Problem ...................................... 15 • The Refugees in the Context of the Middle East Peace Process • Proposed Solutions and Principles Espoused by Israelis and Palestinians Return Statehood Compensation Resettlement Work of non-governmental organizations................................................. 26 • Awareness-Building and Advocacy Work • Humanitarian Assistance and Development • Solidarity With Right of Return and Restitution Conclusion .... ..... ..... ......... ... ....... ..... ....... ....... ....... ... ......... .. .. ... .. ............ -

Israeli Arabs and Jews: Dispelling the Myths, Narrowing the Gaps

I SRA€LI ARABS ANDJ€WS Dispelling the Myths, Narrowing the Gaps Amnon Rubinstein THE AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE The Dorothy and Julius Koppelman Institute on American Jewish-Israeli Relations The American Jewish Committee protects the rights and freedoms of Jews the world over; combats bigotry and anti-Semitism and promotes human rights for all; works for the security of Israel and deepened understanding between Americans and Israelis; advocates public policy positions rooted in American democratic values and the perspectives of the Jewish heritage; and enhances the creative vitality of the Jewish people. Founded in 1906, it is the pioneer human-relations agency in the United States. Israeli Arabs and Jews: Dispelling the Myths, Narrowing the Gaps By Am non Rubinstein Dorothy and Julius Koppelman Institute on American Jewish-Israeli Relationsof the American Jewish Conmmittee The Dorothy and Julius Koppelman Institute on American Jewish-Israeli Relations, founded in 1982 as an arm of the American Jewish Committee, is an interpreter of Israeli and American Jewry to each other, and seeks to build bridges between the world's largest Jewish communities. Specifically, its goals are achieved programmatically through a variety of undertakings, including: • Exchange programs over the years bringingIsraeli politicians, academicians, civil servants, and educators to the United States so that they may learn about the religious pluralism and political dynamism of the American Jewish com- munity. Hundreds of Israelis have participated in these dialogue-oriented mis- sions cosponsored by the Institute and itsIsraeli partners, the Jerusalem Municipality, the Oranim Teacher Training Institute, and the Ministry of Education, Government of Israel. • Studies of the respective communities, particularlyof their interconnectedness, published in both Hebrew and English, in conjunction with the Argov Institute of Bar-han University. -

Download File

Columbia University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Human Rights Studies Master of Arts Program Silencing “Breaking the Silence”: The Israeli government’s agenda respecting human rights NGOs activism since 2009 Ido Dembin Thesis Adviser: Prof. Yinon Cohen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 12 September, 2018 Abstract This research examines a key aspect in the deterioration of Israeli democracy between 2009-2018. Mainly, it looks at Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's Right-wing governments utilization of legislative procedure to limit the right to free speech. The aspects of the right to free speech discussed here pertain to dissenting and critical activism against these government’s policies. The suppression of said right is manifested in the marginalization, delegitimization and ultimately silencing of its expression in Human Rights NGOs activism. To demonstrate this, the research presents a case study of one such NGO – “Breaking the Silence” – and the legal and political actions designed to cause its eventual ousting from mainstream Israeli discourse. The research focuses on the importance and uniqueness of this NGO, as well as the ways in which the government perceives and acts against it. First, it analyzes the NGO’s history, modus operandi and goals, emphasizing the uniqueness that makes it a particularly fascinating case. Then, it researches the government’s specific interest in crippling and limiting its influence. Finally, it highlights the government’s toolbox and utilization thereof against it. By shining a light on this case, the research seeks to show the process of watering down of a fundamental right within Israeli democracy – which is instrumental to understanding the state’s risk of decline towards illiberal democracy. -

A Pre-Feasibility Study on Water Conveyance Routes to the Dead

A PRE-FEASIBILITY STUDY ON WATER CONVEYANCE ROUTES TO THE DEAD SEA Published by Arava Institute for Environmental Studies, Kibbutz Ketura, D.N Hevel Eilot 88840, ISRAEL. Copyright by Willner Bros. Ltd. 2013. All rights reserved. Funded by: Willner Bros Ltd. Publisher: Arava Institute for Environmental Studies Research Team: Samuel E. Willner, Dr. Clive Lipchin, Shira Kronich, Tal Amiel, Nathan Hartshorne and Shae Selix www.arava.org TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 HISTORICAL REVIEW 5 2.1 THE EVOLUTION OF THE MED-DEAD SEA CONVEYANCE PROJECT ................................................................... 7 2.2 THE HISTORY OF THE CONVEYANCE SINCE ISRAELI INDEPENDENCE .................................................................. 9 2.3 UNITED NATIONS INTERVENTION ......................................................................................................... 12 2.4 MULTILATERAL COOPERATION ............................................................................................................ 12 3 MED-DEAD PROJECT BENEFITS 14 3.1 WATER MANAGEMENT IN ISRAEL, JORDAN AND THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY ............................................... 14 3.2 POWER GENERATION IN ISRAEL ........................................................................................................... 18 3.3 ENERGY SECTOR IN THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 20 3.4 POWER GENERATION IN JORDAN ........................................................................................................ -

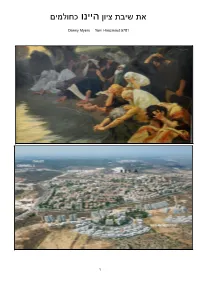

Final Version היינו כחולמים תשפ"א

את שיבת ציון היינו כחולמים Danny Myers Yom Haazmaut 5781 1 Israel-The heart, soul & spirit of the Jew 1. Introduction-The Rav on Israel (1958) Dr. Arnold Lustiger The prayer recited after having partaken of a meal of bread, Birkat Hamazon, is an intricate series of four blessings. In Birkat Hamazon, we thank God for the food, for the land, and for the future rebuilding of Jerusalem, and we conclude with a blessing of gratitude. In the prayer for the land, mention is made of God's covenant of circumcision and the giving of the Torah. A unique aspect of the recitation of Birkat Hamazon is the obligation of Zimun, in which a designated leader introduces responsive statements of blessing to others who have eaten with him. The wording of the responsive statements varies depending on whether the number of participants is three or ten; the Mishnah in Berakhot goes further, detailing a series of variant wordings for one hundred, one thousand, or ten thousand participants, respectively. In contrast, after eating grapes, pomegranates, or figs, the fruits for which the Land of Israel is praised, only one much shorter blessing, the Berakhah Me'ein Shalosh, is recited. Although the themes of land and Jerusalem are also contained in the Berakhah Me'ein Shalosh, they appear in greatly abbreviated form. Allusions to circumcision and the giving of the Torah are entirely absent. The obligation for Zimun, the synchronicity associated with Birkat Hamazon, is also absent in the Berakhah Me'ein Shalosh. a. Ezrah-Man's Partnership with God The halakhic reason for the difference between the blessings recited after the consumption of a meal consisting of bread on one hand and fruit on the other is clearly laid out in the Talmud. -

Family Tree Maker

Descendants of Yankl BLANC Generation No. 1 1. YANKL1 BLANC was born in Podolsk BESSARABIA. He married BRUCHE FAINSTEIN. She was born in Podolsk BESSARABIA. Children of YANKL BLANC and BRUCHE FAINSTEIN are: 2. i. ENRIQUE HERSHEL2 BLANC, b. Escrinia Colonia Dos ARGENTINA. ii. RUJL BLANC, m. LEIV POLIAK. 3. iii. CHONE BAT YANKL BLANC, b. RUSSIAN Empire. 4. iv. SHMIL SHMUEL BLANC, b. 1875, Podolsk BESSARABIA; d. 12 Feb 1968, Kiriat Onu ISRAEL. 5. v. BERKO BERL BLANC, b. Abt. 1892, UKRAYNE ?; d. 21 Nov 1985, Buenos Aires ARGENTINA. Generation No. 2 2. ENRIQUE HERSHEL2 BLANC (YANKL1) was born in Escrinia Colonia Dos ARGENTINA. He married RUCHEL ROSA PASCAR. Children of ENRIQUE BLANC and RUCHEL PASCAR are: 6. i. SALOMON BEN HERSHEL3 BLANC, d. 1968. ii. YOSEF BEN HERSHL BLANC. 7. iii. BERTHA BLANC, b. 08 Aug 1910, Colonia Dos Entre Rios ARGENTINA; d. 10 Dec 1999, ARGENTINA. 3. CHONE BAT YANKL2 BLANC (YANKL1) was born in RUSSIAN Empire. She married YTZCHOK DUJOVNE. He was born in RUSSIAN Empire, and died 14 Feb 1934 in Basavilbaso Entre Rios ARGENTINA. Children of CHONE BLANC and YTZCHOK DUJOVNE are: i. BRACHA3 DUJOVNE, d. ARGENTINA. ii. FANNY DUJOVNE. iii. LEON DUJOVNE. iv. NATALIO DUJOVNE, b. 1906, Basavilbaso E R ARGENTINA; m. ANA KOHAN, Basavilbaso ARGENTINA; b. 1912, Basavilbaso E R ARGENTINA. v. PAULINA DUJOVNE. vi. SAMUEL DUJOVNE, m. TERESA BAT JULIO SCHVARTZ; b. ARGENTINA. vii. SHAUL DUJOVNE, b. Villa Mantero E R ARGENTINA; d. ISRAEL. 8. viii. SHELOMO DUJOVNE, b. 1896, RUSSIAN Empire; d. 1969, ARGENTINA. 9. ix. ISRAEL AZRIEL DUJOVNE, b. -

Allahu Akbar" Becomes a Crime: the Israeli Case

UCLA UCLA Journal of Islamic and Near Eastern Law Title When "Allahu Akbar" Becomes a Crime: The Israeli Case Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7mn483xw Journal UCLA Journal of Islamic and Near Eastern Law, 18(1) Authors Efron, Yael Wattad, Mohammed S. Publication Date 2020 DOI 10.5070/N4181051173 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California WHEN “ALLAHU AKBAR”1 BECOMES A CRIME: The Israeli Case Yael Efron & Mohammed S. Wattad Abstract This Article examines the constitutionality of an Israeli bill that crim- inalizes the use of PA systems in prayer houses, punishable by a fine of 5000–10,000 NIS (the Muezzin Law). The Bill was presented to the Israeli Parliament (the Knesset) as a religiously-neutral environmental law. This Article asserts that a careful reading of the Bill’s language reveals that it is specifically tailored to apply precisely to Muslim prayer houses, thus crimi- nalizing the Muslim call for prayer (the adhan), especially the call occurring between dawn and sunrise (the Fajer adhan). As such, we perceive the Muez- zin law as violating the right to equality and the right to dignity of the Muslim minority in Israel, as well as infringing upon its religious feelings. Addition- ally, we contend that the Muezzin Law is not truly driven by environmental concern, but rather that it represents a conflict with religious dimension (a CRD)—namely, the perception that the adhan, as a Muslim symbol, poses a threat to the identity of Jews in Israel. Examining the constitutionality of the Muezzin Law introduces a crucial question relating to the interplay between constitutional law and criminal law. -

Rethinking the Six Day War: an Analysis of Counterfactual Explanations Limor Bordoley

Limor Bordoley Rethinking the Six Day War: An Analysis of Counterfactual Explanations Limor Bordoley Abstract The Six Day War of June 1967 transformed the political and physical landscape of the Middle East. The war established Israel as a major regional power in the region, while the Israeli territorial acquisitions resulting from the war have permanently marred Israel’s relationship with its Arab neighbors. The May crisis that preceded the war quickly spiraled out of control, leading many to believe that the war was unavoidable. In this paper, I construct three counterfactuals that consider how May and June 1967 might have unfolded differently if a particular event or person in the May crisis had been different. Ultimately, the counterfactuals show that war could have been avoided in three different ways, demonstrating that the Six Day War was certainly avoidable. In the latter half of the paper, I construct a framework to compare the effectiveness of multiple counterfactual. Thus, the objective of this paper is twofold: first, to determine whether war was unavoidable given the political climate and set of relations present in May and June 1967 and second, to create a framework with which one can compare the relative persuasiveness of multiple counterfactuals. Introduction The Six Day War of June 1967 transformed the political and physical landscape of the Middle East. The war established Israel as a major regional power, expanding its territorial boundaries and affirming its military supremacy in the region. The Israeli territorial acquisitions resulting from the war have been a major source of contention in peace talks with the Palestinians, and has permanently marred Israel’s relationship with its Arab neighbors. -

Post-Zionist" Philanthropists: Urging Attitudes of American Jewi Leaders Toward Communal Allocate

Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs Post-Zionist" Philanthropists: urging Attitudes of American Jewi Leaders Toward Communal Allocate Steven M. Cohen and Gerald B. Bubis "POST-ZIONIST" PHILANTHROPISTS: EMERGING ATTITUDES OF AMERICAN JEWISH LEADERS TOWARD COMMUNAL ALLOCATIONS Steven M. Cohen and Gerald B. Bubis Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs 1998 THE JERUSALEM CENTER FOR PUBLIC AFFAIRS The Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs (JCPA), founded in 1976, is an independent, non-profit institute for policy research and education serving Israel and the Jewish people. For more than two decades, the Jerusalem Center has undertaken numerous studies at the request of government and public bodies, and has organized international conferences and seminars with the participation of leading experts from Israel and abroad. Some 300 researchers have participated in the JCPA's various studies, including 70 Center Fellows and Associates. Since its founding, the Center has produced some 700 publications in Hebrew, English, and other languages, which report on the results of research undertaken within its framework. Principal Programs: • Study of Jewish Community Organization: Organized in 1968 to study every organized Jewish community in the world • The Jewish Political Tradition: Begun in 1970 to study this tradition from biblical times to its contemporary manifestations • Institute for Federal Studies: Established in 1976 to study federal solutions to current political problems throughout the world, including the Israeli-Palestinian- Jordanian peace -

The ROMANIAN JOURNAL of SOCIETY and POLITICS

The ROMANIAN JOURNAL of SOCIETY and POLITICS New Series Vol. 12 | No. 2 | December 2017 Faculty of Political Science National University of Political Science and Public Administration All rights reserved 2017 Summary Editorial Note.....................................................................5 William J. Jones Hegemonic Preservation and Thailand’s Douglas Rhein Constitutional Crisis..........................................................7 Trail-blazing: Arab students at the Hebrew University in Kussai Haj-Yehia Jerusalem during the Military Regime (1948-1966) in Israel...................................................................................36 Counterbalancing EU and Russian Soft Power Practices Nino Gozalishvili in Georgia..........................................................................60 BOOK REVIEWS Oana Ghiocea Why Not Socialism? by G. A. Cohen ..............................84 Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Vlad Andrei Terteleac Responsive Government By Christopher H. Achen and Larry M. Bartels................................................................87 Matteo Zanellato Capitalism Without Future by Emanuele Severino..........91 Note on Contributors.......................................................96 5 Editorial Note The Editorial Board of the Romanian Journal of Society and Politics is pleased to announce the launch of the second issue of 2017, namely Volume 12, Number 2. The current issue contains three regular articles and three book reviews, covering topics within the fields -

Family Tree Maker

Descendants of Isaac KUGELMANN Generation No. 1 1. ISAAC5 KUGELMANN (MOSES4, CALMANN3, UNKNOWN BEN CALMANN2, CALMANN (BEN UNKNOWN)1) (Source: Die Geschichte der judischen Gemeinde Korbach, Karl Wilke. 1993.) was born Abt. 1768 (Source: Shlomo Melchior.). He married UNKNOWN (15) UNKNOWN. She was born Abt. 1770. Children of ISAAC KUGELMANN and UNKNOWN UNKNOWN are: 2. i. MOSES6 KUGELMANN, b. 1803, Sachsenhausen Germany. 3. ii. ZITCHEN KUGELMANN, b. Abt. 1808. Generation No. 2 2. MOSES6 KUGELMANN (ISAAC5, MOSES4, CALMANN3, UNKNOWN BEN CALMANN2, CALMANN (BEN UNKNOWN)1) (Source: Die Geschichte der judischen Gemeinde Korbach, Karl Wilke. 1993.) was born 1803 in Sachsenhausen Germany (Source: Die Geschichte der judischen Gemeinde Korbach, Karl Wilke. 1993.). He married RACHEL JACOB (Source: Die Geschichte der judischen Gemeinde Korbach, Karl Wilke. 1993.) 23 06 1835 in Hoeringhausen Germany (Source: (1) marriage certificate, (2) marriage certificate), daughter of SALM JOHANN JACOB. She was born in Sachsenhausen Germany (Source: Die Geschichte der judischen Gemeinde Korbach, Karl Wilke. 1993.), and died 07 01 1889 in Korbach Germany (Source: Die Geschichte der judischen Gemeinde Korbach, Karl Wilke. 1993.). Notes for RACHEL JACOB: First marriage Isaak Rosenberg? Second marriage Moses Kugelmann. Gravestone in Korbach. More About MOSES KUGELMANN and RACHEL JACOB: Marriage: 23 06 1835, Hoeringhausen Germany (Source: (1) marriage certificate, (2) marriage certificate) Children of MOSES KUGELMANN and RACHEL JACOB are: i. BROCHE7 KUGELMANN (Source: (1) Birth Cerificate, (2) Birth Cerificate), b. 01 02 1836, Hoeringhausen Germany (Source: Birth Certificate.). 4. ii. JACOB KUGELMANN, b. 04 03 1838, Hoeringhausen Germany; d. 05 07 1901, Korbach Germany. iii. JOSEPH KUGELMANN (Source: Birth Certificate.), b.