Old and New Covenants: Historical and Theological Contexts in Scribe’S and Halévy’S La Juive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opera, Liberalism, and Antisemitism in Nineteenth-Century France the Politics of Halevy’S´ La Juive

Opera, Liberalism, and Antisemitism in Nineteenth-Century France The Politics of Halevy’s´ La Juive Diana R. Hallman published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Diana R. Hallman 2002 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2002 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Dante MT 10.75/14 pt System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Hallman, Diana R. Opera, liberalism, and antisemitism in nineteenth-century France: the politics of Halevy’s´ La Juive / by Diana R. Hallman. p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in opera) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 65086 0 1. Halevy,´ F., 1799–1862. Juive. 2. Opera – France – 19th century. 3. Antisemitism – France – History – 19th century. 4. Liberalism – France – History – 19th century. i. Title. ii. Series. ml410.h17 h35 2002 782.1 –dc21 2001052446 isbn 0 521 65086 0 -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

L'autorité, 5 Octobre 1895, Pp

JOURNAL DES JEUNES PERSONNES, mai 1862, pp. 195–198. Notre directrice veut, mesdemoiselles, que je vous dise quelques mots du célèbre musicien que la France vient de perdre. La chose n’est pas aisée, et notre directrice le sait bien, car il s’agit de faire un choix entre des œuvres, des faits et des aventures qui se rapportent à une carrière presqu’entièrement consacrée au théâtre. Mais on peut se borner à vous faire apprécier Halévy comme compositeur, comme homme et comme secrétaire perpétuel de l’Académie des Beaux-Arts. C’est ce que je vais essayer de faire; je ne dirai que l’essentiel. Heureux si, grâce à mon sujet, je parviens à vous intéresser! Jacques François-Fromental-Élie Halévy naquit à Paris, le 27 mai 1799, d’une famille israélite, et donna de bonne heure des marques d’une intelligence précoce. Il n’avait pas encore atteint l’âge de dix ans qu’il entra, le 30 janvier 1809, au Conservatoire, dans la classe de solfége de M. Cazot. L’année suivante, il eut pour maître de piano M. Charles Lambert. En 1811, il prit des leçons d’harmonie de Berton; après quoi il travailla pendant cinq ans le contre-point sous la direction de Cherubini, dont il devint l’élève de prédilection. Après dix années d’études musicales assidues et persévérantes, Halévy concourut pour le grand prix de Rome; ce fut à sa cantate d’Herminie qu’il dut le titre de lauréat. Toutefois, il ne partit pas immédiatement pour l’Italie. Il resta à Paris pour mettre en musique le texte hébreu du psaume De profundis, destiné à être chanté dans les synagogues à l’occasion de la mort du duc de Berry, et pour écrire la partition d’un grand opéra intitulé les Bohémiennes qui ne fut point représenté. -

122 a Century of Grand Opera in Philadelphia. Music Is As Old As The

122 A Century of Grand Opera in Philadelphia. A CENTURY OF GRAND OPERA IN PHILADELPHIA. A Historical Summary read before the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Monday Evening, January 12, 1920. BY JOHN CURTIS. Music is as old as the world itself; the Drama dates from before the Christian era. Combined in the form of Grand Opera as we know it today they delighted the Florentines in the sixteenth century, when Peri gave "Dafne" to the world, although the ancient Greeks listened to great choruses as incidents of their comedies and tragedies. Started by Peri, opera gradually found its way to France, Germany, and through Europe. It was the last form of entertainment to cross the At- lantic to the new world, and while some works of the great old-time composers were heard in New York, Charleston and New Orleans in the eighteenth century, Philadelphia did not experience the pleasure until 1818 was drawing to a close, and so this city rounded out its first century of Grand Opera a little more than a year ago. But it was a century full of interest and incident. In those hundred years Philadelphia heard 276 different Grand Operas. Thirty of these were first heard in America on a Philadelphia stage, and fourteen had their first presentation on any stage in this city. There were times when half a dozen travelling companies bid for our patronage each season; now we have one. One year Mr. Hinrichs gave us seven solid months of opera, with seven performances weekly; now we are permitted to attend sixteen performances a year, unless some wandering organization cares to take a chance with us. -

Meyerbeer's Robert Le Diable

Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable : The Premier Opéra Romantique By Robert Ignatius Letellier Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable : The Premier Opéra Romantique , by Robert Ignatius Letellier This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by Robert Ignatius Letellier All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-4191-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-4191-7 Fig. 1 Giacomo Meyerbeer. Lithograph by Delpech after a drawing by Maurin (c. 1836) CONTENTS List of Figures............................................................................................. xi Abbreviations .......................................................................................... xvii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 1. The Origins .............................................................................................. 3 2. The Sources .......................................................................................... 15 The Plot ............................................................................................... -

04-28-2018 Cendrillon Mat.Indd

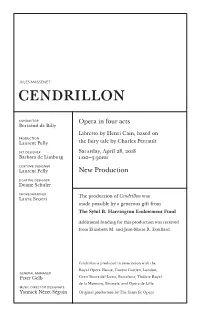

JULES MASSENET cendrillon conductor Opera in four acts Bertrand de Billy Libretto by Henri Cain, based on production Laurent Pelly the fairy tale by Charles Perrault set designer Saturday, April 28, 2018 Barbara de Limburg 1:00–3:50 PM costume designer Laurent Pelly New Production lighting designer Duane Schuler choreographer The production of Cendrillon was Laura Scozzi made possible by a generous gift from The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund Additional funding for this production was received from Elizabeth M. and Jean-Marie R. Eveillard Cendrillon is produced in association with the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; general manager Peter Gelb Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona; Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie, Brussels; and Opéra de Lille. music director designate Yannick Nézet-Séguin Original production by The Santa Fe Opera 2017–18 SEASON The 5th Metropolitan Opera performance of JULES MASSENET’S This performance cendrillon is being broadcast live over The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Opera conductor International Radio Bertrand de Billy Network, sponsored by Toll Brothers, in order of vocal appearance America’s luxury ® homebuilder , with pandolfe the fairy godmother generous long-term Laurent Naouri Kathleen Kim support from The Annenberg madame de la haltière the master of ceremonies Foundation, The Stephanie Blythe* David Leigh** Neubauer Family Foundation, the noémie the dean of the faculty Vincent A. Stabile Ying Fang* Petr Nekoranec** Endowment for Broadcast Media, dorothée the prime minister and contributions Maya Lahyani Jeongcheol Cha from listeners worldwide. lucette, known as cendrillon prince charming Joyce DiDonato Alice Coote There is no Toll Brothers– spirits the king Metropolitan Lianne Coble-Dispensa Bradley Garvin Opera Quiz in Sara Heaton List Hall today. -

Restaging La Juive in a Post-Holocaust Context

RESTAGING LA JUIVE IN A POST-HOLOCAUST CONTEXT Hans-Peter Bayerdörfer Since 1989, Jacques Fromental Halévy’s opera, La Juive, has enjoyed numerous revivals on the European German-language stage, ending an almost seventy-year period of absence. In 1835, when La Juive pre- miered on the Parisian stage, four years after the premiere of Giacomo Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable (1831) and one year before Les Huguenots, the genre of French Grand Opera had reached its apex.1 At the time, the trope of the “beautiful Jewess,” inspired largely by the character of Rebecca in Walter Scott’s novel, Ivanhoe (1820), had gained interna- tional prominence in both theater and literature. It is not surprising, then, that La Juive began its stage career in German-speaking countries soon after it opened in France. Rachel and Eléazar, the opera’s two main characters, joined an established theatrical tradition of Jewish father-daughter constellations that include Nathan and Recha in Less- ing’s Nathan the Wise, Shylock and Jessica in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, and Isaac of York and Rebecca in Heinrich Marschner’s suc- cessful romantic opera, Der Templer und die Jüdin (The Temple Knight and the Jewess, 1829), based on Scott’s novel.2,3 Grand Opera in gen- eral and Halévy’s piece in particular met high expectation and interest in the German countries in the mid 1830s.4 1 For a comprehensive study of the opera see Diana R. Hallman, Opera, Liberalism, and Antisemitism in Nineteenth-Century France: The Politics of Halévy’s La Juive (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002). -

Fromental Halévy and His Operas, 1799-1841

Fromental Halévy and His Operas, 1799-1841 Fromental Halévy and His Operas, 1799-1841 By Robert Ignatius Letellier and Nicholas Lester Fuller Fromental Halévy and His Operas, 1799-1841 By Robert Ignatius Letellier and Nicholas Lester Fuller This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Robert Ignatius Letellier and Nicholas Lester Fuller All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6657-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6657-6 1. Frontispiece: Fromental Halévy young (engraving) CONTENTS List of Figures and Musical Examples ....................................................... ix Volume 1 Life 1. Introduction ............................................................................................. 2 2. Life: François-Joseph Fétis ................................................................... 15 3. A Critical Life in Letters ....................................................................... 20 4. Obituaries: Adolphe Catelin, Saint-Beuve, Édouard Monnais ............ 118 Operas 1. L'Artisan (1827) ................................................................................. 170 2. Le Roi -

Richard Wagner and 19Th-Century Multimedia Entertainments Author(S): Anno Mungen Source: Music in Art, Vol

Research Center for Music Iconography, The Graduate Center, City University of New York Entering the Musical Picture: Richard Wagner and 19th-Century Multimedia Entertainments Author(s): Anno Mungen Source: Music in Art, Vol. 26, No. 1/2 (Spring-Fall 2001), pp. 123-129 Published by: Research Center for Music Iconography, The Graduate Center, City University of New York Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41818660 Accessed: 07-11-2017 23:10 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Research Center for Music Iconography, The Graduate Center, City University of New York is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Music in Art This content downloaded from 70.103.220.4 on Tue, 07 Nov 2017 23:10:38 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Anno Mungen, Wagner and 19th-century Multimedia Entertainments Music in Art XXVI/1-2 (2001) Entering the Musical Picture: Richard Wagner and 19th-century Multimedia Entertainments Anno Mungen Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, Mainz Yes, Wagner is not only an incomparable painter of external nature, of tempest and storm, rustling leaves and dazzle of waves, rainbows and dancing flames. He is also a great seer of animate nature, the eternal human heart.1 Thomas Mann on Der Ring des Nibelungen (1937) Landscape in Simulation. -

Two Operas for One Novel

Two operas for one novel Olivier Bara The rivalry between grand-opéra and opéra-comique dates back to the time of the Théâtres de la Foire, * when vaudevilles and comédies en ariettes fought with the Académie Royale de Musique for the right to sing on stage. There were a number of overlaps from one theatre to another, ini - tially in the form of parodies, then of duplications, when the same sub - ject was treated at the Opéra and at the Opéra-Comique, in the ‘grand style’ ( grand genre ) at the former and the ‘intermediate style’ ( genre moyen ) at the latter. This might mean a recasting of the libretto and the score, as in the case of Robert le diable , initially conceived for the Opéra-Comique as a continuation of the medieval vein of La Dame blanche . Each institu - tion could also handle a single subject in two distinct works, as with Carafa’s Masaniello , premiered at the Opéra-Comique in 1827 two months before Auber’s La Muette de Portici at the Opéra. Such is also the case with Le Pré aux clercs , which anticipates by four years Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots , given its first performance at the Opéra on 29 February 1836. The relationship of Le Pré aux clercs and Les Huguenots to Mérimée’s novel Chronique du règne de Charles IX , the direct source of the opéra- comique and a more distant point of reference for the grand-opéra , sheds light on their respective and distinct dramaturgies. Is Mérimée’s work closer in spirit, in tone, in historical vision, to the ‘demi-caractère’ (semi- ——— * The ‘Fair Theatres’, originally held at the Foire Saint-Germain and Foire Saint- Laurent in Paris, which were the forerunners of the Opéra-Comique. -

La Juive L’Ebrea

1 La Fenice prima dell’Opera 2005-2006 1 2005-2006 Fondazione Stagione 2005-2006 Teatro La Fenice di Venezia Lirica e Balletto Fromental Halévy LA L’ebreaJuive a juive L alévy H romental romental F FONDAZIONE TEATRO LA FENICE DI VENEZIA VENEZIA Calle Larga XXII Marzo, 2098 ALBO DEI SOCI FONDATORI ALBO DEI SOCI FONDATORI La Fondazione Teatro La Fenice di Venezia ringrazia per il contributo ESATOUR - OPERA AND MUSIC TRAVEL LA FUGUE EUROPÉRA VENICE À LA CARTE SRL BORMIOLI ROCCO E FIGLIO S.P.A FRA DIAVOLO SAN MARCO HOTELS EURIDICE OPERA SÉJOURS CULTURELS LIAISONS ABROAD LTD GABY AGHAJANIAN WILLI E SOLANGE STRICKER JEAN E BARBARA LEVI PATRICK E KARIN SALOMON JEAN PIERRE E DOMINIQUE FRANTZ REINOLD E DOMINIQUE GEIGERT PHILIPPE LEFEVRE E SYVIA SPALTER NEVILLE E ALEXANDRA COOK PIERRE E MYRTA SANDRE JEAN PIERRE E BRIGITTE FLOCHEL KAYHLEEN LIPKOWSKI KASPAR ANGEL COLLADO-SCHWARZ RHIAG GROUP LTD ARMIDA E MANLIO ARMELLINI CETTINA E ROSARIO MESSINA «MUSICA JUNTOS» DI MADRID PLB ORGANISATION IL SIPARIO MUSICALE CASSA DI RISPARMIO DI VENEZIA A.N.C.V. S.C.A R.L., PAOLO JUCKER E GIOVANNA PITTERI CLAUDE E BRIGITTE DEVER RUBELLI S.P.A. CONSIGLIO DI AMMINISTRAZIONE Massimo Cacciari presidente Luigino Rossi vicepresidente Cesare De Michelis Pierdomenico Gallo Achille Rosario Grasso Mario Rigo Valter Varotto Giampaolo Vianello consiglieri sovrintendente Giampaolo Vianello direttore artistico Sergio Segalini COLLEGIO DEI REVISORI DEI CONTI Giancarlo Giordano presidente Adriano Olivetti Paolo Vigo Maurizia Zuanich Fischer SOCIETÀ DI REVISIONE PricewaterhouseCoopers S.p.A. la juive L’ebrea opera in cinque atti libretto di Eugène Scribe musica di Fromental Halévy Teatro La Fenice venerdì 11 novembre 2005 ore 19.00 turno A domenica 13 novembre 2005 ore 15.30 turno C martedì 15 novembre 2005 ore 19.00 turno D giovedì 17 novembre 2005 ore 19.00 fuori abb. -

Venetian Terreur, French Heroism and Fated Love

Venetian terreur , French heroism and fated love Diana R. Hallman The tales of history, so captivating to French readers and theatregoers of the early nineteenth century, flourished on the stage of the Paris Opéra in grand opéra portrayals of intimate tragedies set against events and con - flicts of the distant past – from the 1647 revolt of Neapolitan peasants against Spanish rule in Daniel-François-Esprit Auber’s La Muette de Portici (1828) to the 1572 Saint-Barthélemy Massacre of Huguenots in Giacomo Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots (1836). Fromental Halévy (179 9- 1862), a leading grand opéra composer who had depicted the historical Cardinal Brogni and Council of Constance of 141 4- 18 in Eugène Scribe’s invented story of Jewish-Christian romance and opposition in La Juive (1835), would again be drawn to fifteenth-century history in his third grand opéra, La Reine de Chypre, written in collaboration with the librettist Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges (179 9- 1875). In setting Saint-Georges’s reimagined story of the Venetian-born Cypriot queen Catarina Cornaro, Halévy undoubtedly sensed the theatrical appeal of Catarina’s thwarted marriage, the conflicted rivalry of exiled French knights who claimed her hand, and the musical-dramatic colours promised by exotic, festive scenes in Venice and Cyprus. Moreover, he may have been touched by nostalgia for Italy, a country that he had enthusiastically explored during his early Prix de Rome years. But, according to the composer’s brother, artistic partner and biographer Léon Halévy, an important inspiration for this opera of 65 fromental halévy: la reine de chypre 1841 was the ‘sombre et mystérieuse terreur’ of Venice, an image that tapped into a rich vein of politically charged representations of the Venetian Republic that either alluded to or overtly condemned the secretive des - potism of its early patrician rulers.