Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Meyerbeer Was One of the Most Significant Opera Composers of All Time

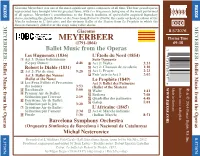

NAXOS NAXOS Giacomo Meyerbeer was one of the most significant opera composers of all time. The four grand operas represented here brought him his greatest fame, with Les Huguenots being one of the most performed of all operas. Meyerbeer’s contributions to the French tradition of opéra-ballet acquired legendary status, including the ghostly Ballet of the Nuns from Robert le Diable; the exotic orchestral colour of the Marche indienne in L’Africaine; and the virtuoso Ballet of the Skaters from Le Prophète in which the dancers famously glided over the stage using roller skates. DDD MEYERBEER: MEYERBEER: Giacomo 8.573076 MEYERBEER Playing Time (1791-1864) 69:38 Ballet Music from the Operas 7 Les Huguenots (1836) L’Étoile du Nord (1854) 47313 30767 1 Act 3: Danse bohémienne Suite Dansante Ballet Music from the Operas Ballet Music from (Gypsy Dance) 4:46 9 Act 2: Waltz 3:32 the Operas Ballet Music from Robert le Diable (1831) 0 Act 2: Chanson de cavalerie 1:18 2 Act 2: Pas de cinq 9:28 ! Act 1: Prayer 2:23 Act 3: Ballet des Nonnes @ Entr’acte to Act 3 2:02 (Ballet of the Nuns) Le Prophète (1849) 3 Les Feux Follets et Procession Act 3: Ballet des Patineurs 8 des nonnes 3:53 (Ballet of the Skaters) www.naxos.com Made in Germany Booklet notes in English ൿ 4 Bacchanale 5:00 # Waltz 1:41 & 5 Premier Air de Ballet: $ Redowa 7:08 Ꭿ Séduction par l’ivresse 2:19 % Quadrilles des patineurs 4:48 6 Deuxième Air de Ballet: 2014 Naxos Rights US, Inc. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

VOCAL 78 Rpm Discs Minimum Bid As Indicated Per Item

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs Minimum bid as indicated per item. Listings “Just about 1-2” should be considered as mint and “Cons. 2” with just the slightest marks. For collectors searching top copies, you’ve come to the right place! The further we get from the time of production (in many cases now 100 years or more), the more difficult it is to find such excellent extant pressings. Some are actually from mint dealer stocks and others the result of having improved copies via dozens of collections purchased over the past fifty years. * * * For those looking for the best sound via modern reproduction, those items marked “late” are usually of high quality shellac, pressed in the 1950-55 period. A number of items in this particular catalogue are excellent pressings from that era. * * * Please keep in mind that the minimum bids are in U.S. Dollars, a benefit to most collectors. * * * “Text label on verso.” For a brief period (1912-14), Victor pressed silver-on-black labels on the reverse sides of some of their single-faced recordings, usually with a translation of the text or similarly related comments. BESSIE ABOTT [s]. Riverdale, NY, 1878-New York, 1919. Following the death of her father which left her family penniless, Bessie and her sister Jessie (born Pickens) formed a vaudeville sister vocal act, accompanying themselves on banjo and guitar. Upon the recommendation of Jean de Reszke, who heard them by chance, Bessie began operatic training with Frida Ashforth. She subsequently studied with de Reszke him- self and appeared with him at the Paris Opéra, making her debut as Gounod’s Juliette. -

Otello Program

GIUSEPPE VERDI otello conductor Opera in four acts Gustavo Dudamel Libretto by Arrigo Boito, based on production Bartlett Sher the play by William Shakespeare set designer Thursday, January 10, 2019 Es Devlin 7:30–10:30 PM costume designer Catherine Zuber Last time this season lighting designer Donald Holder projection designer Luke Halls The production of Otello was made possible by revival stage director Gina Lapinski a generous gift from Jacqueline Desmarais, in memory of Paul G. Desmarais Sr. The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 345th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S otello conductor Gustavo Dudamel in order of vocal appearance montano a her ald Jeff Mattsey Kidon Choi** cassio lodovico Alexey Dolgov James Morris iago Željko Lučić roderigo Chad Shelton otello Stuart Skelton desdemona Sonya Yoncheva This performance is being broadcast live on Metropolitan emilia Opera Radio on Jennifer Johnson Cano* SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Thursday, January 10, 2019, 7:30–10:30PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA Stuart Skelton in Chorus Master Donald Palumbo the title role and Fight Director B. H. Barry Sonya Yoncheva Musical Preparation Dennis Giauque, Howard Watkins*, as Desdemona in Verdi’s Otello J. David Jackson, and Carol Isaac Assistant Stage Directors Shawna Lucey and Paula Williams Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter Prompter Carol Isaac Italian Coach Hemdi Kfir Met Titles Sonya Friedman Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Assistant Scenic Designer, Properties Scott Laule Assistant Costume Designers Ryan Park and Wilberth Gonzalez Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department; Angels the Costumiers, London; Das Gewand GmbH, Düsseldorf; and Seams Unlimited, Racine, Wisconsin Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department This production uses strobe effects. -

Opera, Liberalism, and Antisemitism in Nineteenth-Century France the Politics of Halevy’S´ La Juive

Opera, Liberalism, and Antisemitism in Nineteenth-Century France The Politics of Halevy’s´ La Juive Diana R. Hallman published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Diana R. Hallman 2002 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2002 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Dante MT 10.75/14 pt System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Hallman, Diana R. Opera, liberalism, and antisemitism in nineteenth-century France: the politics of Halevy’s´ La Juive / by Diana R. Hallman. p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in opera) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 65086 0 1. Halevy,´ F., 1799–1862. Juive. 2. Opera – France – 19th century. 3. Antisemitism – France – History – 19th century. 4. Liberalism – France – History – 19th century. i. Title. ii. Series. ml410.h17 h35 2002 782.1 –dc21 2001052446 isbn 0 521 65086 0 -

Edouard De Reszke: the Career of a Famous Basso

Edouard de Reszke: The Career of a Famous Basso. 1855-1917 Author(s): Herman Klein Source: The Musical Times, Vol. 58, No. 893 (Jul. 1, 1917), pp. 301-302 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/908418 Accessed: 30-01-2016 05:05 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.51.1.212 on Sat, 30 Jan 2016 05:05:36 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE MUSICAL TIMES.-JULY I, 1917. 30o as remainderthe segment measuring iooo mm.,emitting For Edouard de Reszke had also been here before.* an Eb in the ratio 12: 10 with the apparent tonic or With a four years' stage career behind him he had string note C, with which it accordingly forms a correct made his dbuit at Covent Garden in i880 as Indra in minor third. In its genesis from its generator, G, Massenet's 'Roi de Lahore,' a novelty of the previous this Et is seen to be the major third of the ratio 0 : 8, season, with Gayarre, Lassalle, and Albani in the which with the C gives the common chord on G principal parts. -

Tour Du Monde (1) – Déc.14-Janv.15

www.falcinelli.org Un Tour du monde par étapes discographiques Du Brésil à l’Italie Antônio Carlos Gomes : Salvator Rosa. Opéra en 4 actes, avec Dae-Bum Lee (Il Duca d’Arcos), Ray M. Wade Jr. (Salvator Rosa), Maria Porubcinova (Isabella), Malte Roesner (Masaniello), Simone Lichtenstein (Gennariello), Chœur et Orchestre du Staatstheater de Braunschweig, dir. Georg Menskes. Oehms (2 CDs) OC 957. Le compositeur brésilien dont je vous entretiens aujourd’hui n’eut rien d’un inconnu (le passé s’impose, hélas !), il connut même d’éclatants succès… à la Scala de Milan. Il naquit en 1836 à Campinas (état de São Paulo), son grand-père était espagnol (et non portugais comme l’affirme Danilo Prefumo dans la notice du coffret) et sa grand-mère une indigène guarani ; on ne pouvait guère reprocher à celui qui signait A. Carlos Gomes (probablement pour éviter toute confusion orthographique entre Antônio version luso-brésilienne, et Antonio pour les affiches italiennes) d’être étranger au sujet lorsqu’il fit triompher sur la scène de la Scala le 19 mars 1870 un ouvrage intitulé Il Guarany, avec un jeune baryton qui devait plus tard s’illustrer dans les rôles d’Amonasro, Simon Boccanegra, Iago et Falstaff : Victor Maurel. Car notre Brésilien venu poursuivre ses études musicales puis quérir les recettes du succès en Italie s’inspira évidemment de Verdi dont il assimila l’évolution dramatique et orchestrale. Il représente avec son contemporain Amilcare Ponchielli une génération intermédiaire, non dénuée d’intérêt, mais dont l’heure fut dépassée aussitôt après -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

The German Romantic Movement

The German Romantic Movement Start date 27 March 2020 End date 29 March 2020 Venue Madingley Hall Madingley Cambridge CB23 8AQ Tutor Dr Robert Letellier Course code 1920NRX040 Director of ISP and LL Sarah Ormrod For further information on this Zara Kuckelhaus, Fleur Kerrecoe course, please contact the Lifelong [email protected] or 01223 764637 Learning team To book See: www.ice.cam.ac.uk or telephone 01223 746262 Tutor biography Robert Ignatius Letellier is a lecturer and author and has presented some 30 courses in music, literature and cultural history at ICE since 2002. Educated in Grahamstown, Salzburg, Rome and Jerusalem, he is a member of Trinity College (Cambridge), the Meyerbeer Institute Schloss Thurmau (University of Bayreuth), the Salzburg Centre for Research in the Early English Novel (University of Salzburg) and the Maryvale Institute (Birmingham) as well as a panel tutor at ICE. Robert's publications number over 100 items, including books and articles on the late seventeenth-, eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century novel (particularly the Gothic Novel and Sir Walter Scott), the Bible, and European culture. He has specialized in the Romantic opera, especially the work of Giacomo Meyerbeer (a four-volume English edition of his diaries, critical studies, and two analyses of the operas), the opera-comique and Daniel-François-Esprit Auber, Operetta, the Romantic Ballet and Ludwig Minkus. He has also worked with the BBC, the Royal Opera House, Naxos International and Marston Records, in the researching and preparation of productions. University of Cambridge Institute of Continuing Education, Madingley Hall, Cambridge, CB23 8AQ www.ice.cam.ac.uk Course programme Friday Please plan to arrive between 16:30 and 18:30. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert Le Diable Online

cXKt6 [Get free] The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable Online [cXKt6.ebook] The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable Pdf Free Richard Arsenty ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #4398313 in Books 2009-03-01Format: UnabridgedOriginal language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.00 x .50 x 5.70l, .52 #File Name: 1847189644180 pages | File size: 19.Mb Richard Arsenty : The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Liobretto for Meyerbeer's "Robert le Diable"By radamesAn excellent publication which contained many stage directions not always reproduced in the nineteenth-century vocal scores and a fine translation. Useful at a time of renewed interest in this opera at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden Giacomo Meyerbeer, one of the most important and influential opera composers of the nineteenth century, enjoyed a fame during his lifetime hardly rivaled by any of his contemporaries. This eleven volume set provides in one collection all the operatic texts set by Meyerbeer in his career. The texts offer the most complete versions available. Each libretto is translated into modern English by Richard Arsenty; and each work is introduced by Robert Letellier. In this comprehensive edition of Meyerbeer's libretti, the original text and its translation are placed on facing pages for ease of use. About the AuthorRichard Arsenty, a native of the U.S.