HISTORICAL CONTEXT Historical Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boca Raton and the Florida Land Boom of the 1920S

20 TEQUESTA Boca Raton and the Florida Land Boom of the 1920s by Donald W. Curl The Florida land boom of 1924-25 is commonly mentioned by historians of the twenties and of the South. Most of them see the boom as a phenomenon of the Miami area, though they usually mention in passing that no part of the state remained immune to the speculation fever. Certainly Miami's developments received major attention from the national press and compiled amazing financial statistics for sales and inflated prices. Still, similar activity took place throughout the state. Moreover, the real estate boom in Palm Beach County began as early as that in Miami, contained schemes that equaled that city's in their imagination and fantasy, and also captured national attention. Finally, one of these schemes, that of Addison Mizner's Boca Raton, probably served as the catalyst for exploiting the boom bubble. The Florida land boom resulted from a number of complex fac- tors. Obviously, the mild winter climate had drawn visitors to the state since the Civil War. Summer was said "to spend the winter in West Palm Beach." Now with the completion of the network of roads known as the Dixie Highway and the increasing use of the automobile, Florida became easily accessible to the cities of the northeast and midwest. For some, revolting against the growing urbanization of the north, Florida became "the last frontier." Others found romance in the state's long and colorful history and "fascination in her tropical vege- tation and scenery." Many were confident in the lasting nature of the Coolidge prosperity, and, hearing the success stories of the earliest Donald W. -

On the Shady Side: Escape the Heat to San Diego's Coolest Spots by Ondine Brooks Kuraoka

Publication Details: San Diego Family Magazine July 2004 pp. 28-29, 31 Approximately 1,400 words On the Shady Side: Escape the Heat to San Diego's Coolest Spots by Ondine Brooks Kuraoka During the dog days of summer, it’s tempting to hunker down inside until the temperature drops. Cabin fever can hit hard, though, especially with little ones. If we don’t have air conditioning we hit the mall, or stake out a booth at Denny’s, or do time at one of the wild pizza arcades when we’re desperate. Of course, we can always head to the beach. But we yearn for places where energetic little legs can run amok and avoid the burning rays. Luckily, there is a slew of family-friendly, shady glens nestled between the sunny stretches of San Diego. First stop: Balboa Park (www.balboapark.org ). The Secret is Out While you’re huffing a sweaty path to your museum of choice, the smiling folks whizzing by on the jovial red Park Tram are getting a free ride! Park in the lot at Inspiration Point on the east side of Park Blvd., right off of Presidents Way, and wait no longer than 15 minutes at Tram Central, a shady arbor with benches. The Tram goes to the Balboa Park Visitors Center (619-239-0512), where you can get maps and souvenirs, open daily from 9 a.m.. to 4 p.m. Continuing down to Sixth Avenue, the Tram then trundles back to the Pan American Plaza near the Hall of Champions Sports Museum. -

In Plain Sight Design Duo Miguel Urquijo and Renate Kastner Have Used the Vast Plains of Central Spain As Inspiration for This Stylish Private Garden

spanish garden In plain sight Design duo Miguel Urquijo and Renate Kastner have used the vast plains of central Spain as inspiration for this stylish private garden WORDS NOËL KINGSBURY PHOTOGRAPHS CLAIRE TAKACS In brief What Private garden on a country estate. Where South of Salamanca, Spain. Size Around 5,000 square metres. Climate Mediterranean/continental with sharp, overnight frosts in winter and temperatures reaching 40ºC in summer. Soil Imported clay loam. Hardiness rating USDA 8. In this private garden in central Spain, designers Miguel Urquijo and Renate Kastner have kept grass, and so irrigation, to a minimum, using repeat plantings of the drought-tolerant Lavandula angustifolia to link the house to its wider landscape. 65 spanish garden entral Spain is ‘big sky’ country, where the scale of the landscape Ctends to render attempts at garden making seem puny by comparison. Although this design is deeply rooted in the A high rolling plain, often backed by distant mountains, this is a Spanish landscape, Miguel fell in love with landscape that every now and again offers truly immense vistas; it has scale that is unlike anything else in Europe, and at times feels gardening in England while studying biology more like the American west or central Asia. It was in this vast landscape that the design partnership of Miguel Urquijo and Renate Kastner faced the challenge of creating a stylish green-looking design for a private garden. “The client wanted grass, rather than gravel,” says Miguel,“but we were determined to reduce water use.” Miguel also felt an island of green grass would cut the house off from the surrounding countryside. -

The Surrounds Layout and Form of Spanish Mission

THE SURROUNDS LAYOUT AND FORM OF SPANISH MISSION STYLE GARDENS OF THE 1920s GRADUATE REPORT FOR THE MASTER OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT (CONSERVATION) UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES D M TAYLOR B Larch 1989 UNIVERSITY OF N.S.W. 2 9 JUN 1990 LIBRARY TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE ABSTRACT iv INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 ORIGIN OF SPANISH MISSION STYLE 2 2 INTRODUCTION TO SPANISH MISSION IN AUSTRALIA 8 3 THE ARCHITECTURE OF SPANISH MISSION 1 9 4 INTRODUCTION TO AUSTRALIAN GARDEN DESIGN IN THE 1920S 30 5 SURROUNDS TO SPANISH MISSION 3 8 CONCLUSION 6 5 REFERENCES 6 7 APPENDIX I CONSERVATION GUIDELINES 6 9 II 1920s TYPICAL GARDEN FOR A BUNGALOW 7 3 III SPANISH MISSION GARDEN AT MOSMAN, NSW 7 5 BIBLIOGRAPHY 7 8 ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Page Fig 1 11 Fig 2 14 Fig 3 15 Figs 4 and 5 17 Fig 6 18 Fig 7 21 Fig 8 23 Fig 9 24 Fig 10 28 Fig 11 33 Fig 12 34 Fig 13 44 Figs 14 and 15 46 Fig 16 47 Figs 17 and 18 49 Fig 19 50 Fig 20 54 Figs 21 and 22 58 Figs 23 and 24 59 Figs 25 and 26 60 Fig 27 and 28 62 Fig 29 64 Fig 30 73 Fig 31 75 Fig 32 77 ill ABSTRACT This report examines the surrounds to Spanish Mission houses in the following areas: (i) Spanish Mission Style of architecture, its origins and adaptation to residential and commercial types in California from around 1890 to 1915 (ii) The introduction of Spanish Mission architecture into Australia and its rise in popularity from 1925 through to around 1936. -

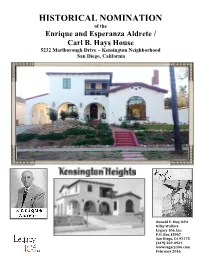

HISTORICAL NOMINATION of the Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B

HISTORICAL NOMINATION of the Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B. Hays House 5232 Marlborough Drive ~ Kensington Neighborhood San Diego, California Ronald V. May, RPA Kiley Wallace Legacy 106, Inc. P.O. Box 15967 San Diego, CA 92175 (619) 269-3924 www.legacy106.com February 2016 1 HISTORIC HOUSE RESEARCH Ronald V. May, RPA, President and Principal Investigator Kiley Wallace, Vice President and Architectural Historian P.O. Box 15967 • San Diego, CA 92175 Phone (619) 269-3924 • http://www.legacy106.com 2 3 State of California – The Resources Agency Primary # ___________________________________ DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # ______________________________________ PRIMARY RECORD Trinomial __________________________________ NRHP Status Code 3S Other Listings ___________________________________________________________ Review Code _____ Reviewer ____________________________ Date __________ Page 3 of 38 *Resource Name or #: The Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B. Hays House P1. Other Identifier: 5232 Marlborough Drive, San Diego, CA 92116 *P2. Location: Not for Publication Unrestricted *a. County: San Diego and (P2b and P2c or P2d. Attach a Location Map as necessary.) *b. USGS 7.5' Quad: La Mesa Date: 1997 Maptech, Inc.T ; R ; ¼ of ¼ of Sec ; M.D. B.M. c. Address: 5232 Marlborough Dr. City: San Diego Zip: 92116 d. UTM: Zone: 11 ; mE/ mN (G.P.S.) e. Other Locational Data: (e.g., parcel #, directions to resource, elevation, etc.) Elevation: 380 feet Legal Description: Lots Three Hundred Twenty-three and Three Hundred Twenty-four of KENSINGTON HEIGHTS UNIT NO. 3, according to Map thereof No. 1948, filed in the Office of the County Recorder, San Diego County, September 28, 1926. It is APN # 440-044-08-00 and 440-044-09-00. -

The Architectural Style of Bay Pines VAMC

The Architectural Style of Bay Pines VAMC Lauren Webb July 2011 The architectural style of the original buildings at Bay Pines VA Medical Center is most often described as “Mediterranean Revival,” “Neo-Baroque,” or—somewhat rarely—“Churrigueresque.” However, with the shortage of similar buildings in the surrounding area and the chronological distance between the facility’s 1933 construction and Baroque’s popularity in the 17th and 18th centuries, it is often wondered how such a style came to be chosen for Bay Pines. This paper is an attempt to first, briefly explain the Baroque and Churrigueresque styles in Spain and Spanish America, second, outline the renewal of Spanish-inspired architecture in North American during the early 20th century, and finally, indicate some of the characteristics in the original buildings which mark Bay Pines as a Spanish Baroque- inspired building. The Spanish Baroque and Churrigueresque The Baroque style can be succinctly defined as “a style of artistic expression prevalent especially in the 17th century that is marked by use of complex forms, bold ornamentation, and the juxtaposition of contrasting elements.” But the beauty of these contrasting elements can be traced over centuries, particularly for the Spanish Baroque, through the evolution of design and the input of various cultures living in and interacting with Spain over that time. Much of the ornamentation of the Spanish Baroque can be traced as far back as the twelfth century, when Moorish and Arabesque design dominated the architectural scene, often referred to as the Mudéjar style. During the time of relative peace between Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Spain— the Convivencia—these Arabic designs were incorporated into synagogues and cathedrals, along with mosques. -

Arciiltecture

· BALBOA PARK· CENTRAL MESA PRECISE PLAN Precise Plan • Architecture ARCIIlTECTURE The goal of this section is to rehabilitate and modify the architecture of the Central Mesa ina manner which preserves its historic and aesthetic significance while providing for functional needs. The existing structures built for the 1915 and the 1935 Expositions are both historically and architecturally significant and should be reconstructed or rehabilitated. Not only should the individual structures be preserved, but the entire ensemble in its original composition should be preserved and restored wherever possible. It is the historic relationship between the built and the outdoor environment that is the hallmark of the two Expositions. Because each structure affects its site context to such a great degree, it is vital to the preservation of the historic district that every effort be made to preserve and restore original Exposition building footprints and elevations wherever possible. For this reason, emphasis has been placed on minimizing architectural additions unless they are reconstructions of significant historical features. Five major types of architectural modifications are recommended for the Central Mesa and are briefly described below. 1. Preservation and maintenance of existing structures. In the case of historically significant architecture, this involves preserving the historical significance of the structure and restoring lost historical features wherever possible. Buildings which are not historically significant should be preserved and maintained in good condition. 2. Reconstructions . This type of modification involves the reconstruction of historic buildings that have deteriorated to a point that prevents rehabilitation of the existing structure. This type of modification also includes the reconstruction of historically significant architectural features that have been lost. -

Home & Garden Issue

HOME & GARDEN ISSUE TeaPartySocietyMagazineNov09:Layout 1 9/30/09 11:16 AM Page 1 NATURALLY, YOU’LL WANT TO DO A LITTLE ENTERTAINING. Sometimes it’s the little moments that Septem matter most. Like when your children New d learn values that last a lifetime. Or laughter is shared for the sheer joy of it. That’s why families find it so easy to feel at home at Sherwood. Nestled in a lush valley of the Santa Monica Mountains, this gated country club community provides a sanctuary for gracious living and time well spent. Of course, with a respected address like Sherwood there may be times when you entertain on a grander scale, but it might just be the little parties that you remember most. For information about custom homesites available from $500,000, new residences offered from the high $1,000,000s or membership in Sherwood Lake Club please call 805-373-5992 or visit www.sherwoodcc.com. The Sherwood Lake Club is a separate country club that is not affiliated with Sherwood Country Club. Purchase of a custom homesite or new home does not include membership in Sherwood Country Club or Sherwood Lake Club or any rights to use private club facilities. Please contact Sherwood Country Club directly for any information on Sherwood Country Club. Prices and terms effective date of publication and subject to change without notice. CA DRE #01059113 A Community 2657-DejaunJewelers.qxd:2657-DejaunJewelers 1/6/10 2:16 PM Page 1 WHY SETTLE FOR LESS THAN PERFECTION The Hearts On Fire Diamond Engagement Ring set in platinum starting at $1,950 View our entire collection at heartsonfire.com Westfield Fashion Square | Sherman Oaks | 818.783.3960 North Ranch Mall | Westlake Village | 805.373.1002 The Oaks Shopping Center | Thousand Oaks | 805.495.1425 www.dejaun.com Welcome to the ultimate Happy Hour. -

Boca Raton, Florida 1 Boca Raton, Florida

Boca Raton, Florida 1 Boca Raton, Florida City of Boca Raton — City — Downtown Boca Raton skyline, seen northwest from the observation tower of the Gumbo Limbo Environmental Complex Seal Nickname(s): A City for All Seasons Location in Palm Beach County, Florida Coordinates: 26°22′7″N 80°6′0″W Country United States State Florida County Palm Beach Settled 1895 Boca Raton, Florida 2 Incorporated (town) May, 1925 Government - Type Commission-manager - Mayor Susan Whelchel (N) Area - Total 29.1 sq mi (75.4 km2) - Land 27.2 sq mi (70.4 km2) - Water 29.1 sq mi (5.0 km2) Elevation 13 ft (4 m) Population - Total 86396 ('06 estimate) - Density 2682.8/sq mi (1061.7/km2) Time zone EST (UTC-5) - Summer (DST) EDT (UTC-4) ZIP code(s) Area code(s) 561 [1] FIPS code 12-07300 [2] GNIS feature ID 0279123 [3] Website www.ci.boca-raton.fl.us Boca Raton (pronounced /ˈboʊkə rəˈtoʊn/) is a city in Palm Beach County, Florida, USA, incorporated in May 1925. In the 2000 census, the city had a total population of 74,764; the 2006 population recorded by the U.S. Census Bureau was 86,396.[4] However, the majority of the people under the postal address of Boca Raton, about 200,000[5] in total, are not actually within the City of Boca Raton's municipal boundaries. It is estimated that on any given day, there are roughly 350,000 people in the city itself.[6] In terms of both population and land area, Boca Raton is the largest city between West Palm Beach and Pompano Beach, Broward County. -

Guide of Granada

Official guide City of Granada 3 Open doors To the past. To the future. To fusion. To mix. To the north. To the south. To the stars. To history. To the cutting edge. To the night. To the horizon. To adventure. To contemplation. To the body. To the mind. To fun. To culture. Open all year. Open to the world. Welcome The story of a name or a name for history 5TH CENTURY B.C.: the Turduli founded Elybirge. 2ND CENTURY B.C.: the Romans settled in Florentia Iliberitana. 1ST CENTURY: according to tradition, San Cecilio, the patron saint of the city, Christianised Iliberis. 7TH CENTURY: the Visigoths fortified Iliberia. 8TH CENTURY: the Arabs arrived in Ilvira. 11TH CENTURY: the Zirids moved their capital to Medina Garnata. 15TH CENTURY: Boabdil surrendered the keys of Granada to the Catholic Monarchs. Today, we still call this city GRANADA which, over its 25 century–history, has been the pride of all those who lived in it, defended it, those who lost it and those who won it. 25 centuries of inhabitants have given the city, apart from its different names, its multicultural nature, its diversity of monuments, religious and secular works of art, its roots and its sights and sounds only to be found in Granada. Iberians, Romans, Arabs, Jews and Christians have all considered this Granada to be their own, this Granada that is today the embodiment of diversity and harmonious coexistence. Since the 19th century, Granada has also been the perfect setting for those romantic travellers that had years on end free: the American Washington Irving, with his Tales of the Alhambra (1832), captivated writers, artists and musicians of his generation, telling them about that “fiercely magnificent” place that also fascinated Victor Hugo and Chateaubriand. -

Manifiesto De La Alhambra English

Fernando Chueca Goitia and others The Alhambra Manifesto (1953) Translated by Jacob Moore Word Count: 2,171 Source: Manifiesto de la Alhambra (Madrid, Dirección General de Arquitectura, 1953). Republished as El Manifiesto de la Alhambra: 50 años después: el monumento y la arquitectura contemporánea, ed. Ángel Isac, (Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife, Consejería de Cultura, Junta de Andalucía : Tf Editores, 2006) 356-375. We, the signers of this Manifesto, do not want to be pure iconoclasts, for we are already too weary of such abrupt and arbitrary turns. So people will say: “Why the need for a Manifesto, a term which, almost by definition, implies a text that is dogmatic and revolutionary, one that breaks from the past, a public declaration of a new credo?” Simply put, because reality, whose unequivocal signs leave no room for doubt, is showing us that the ultimate traditionalist posture, which architecture adopted after the war of Liberation, can already no longer be sustained and its tenets are beginning to fall apart. […] Today the moment of historical resurrections has passed. There is no use denying it; just as one cannot deny the existence of the Renaissance in its time or that of the nineteenth century archaeological revivals. The arts have tired of hackneyed academic models and of cold, lifeless copies, and seek new avenues of expression that, though lacking the perfection of those that are known, are more radical and authentic. But one must also not forget that the peculiar conditions implicit in all that is Spanish require that, within the global historical movement, we move forward, we would not say with a certain prudence, but yes, adjusting realities in our own way. -

Balboa Park Facilities

';'fl 0 BalboaPark Cl ub a) Timken MuseumofArt ~ '------___J .__ _________ _J o,"'".__ _____ __, 8 PalisadesBuilding fDLily Pond ,------,r-----,- U.,..p_a_s ..,.t,..._---~ i3.~------ a MarieHitchcock Puppet Theatre G BotanicalBuild ing - D b RecitalHall Q) Casade l Prado \ l::..-=--=--=---:::-- c Parkand Recreation Department a Casadel Prado Patio A Q SanD iegoAutomot iveMuseum b Casadel Prado Pat io B ca 0 SanD iegoAerospace Museum c Casadel Prado Theate r • StarlightBow l G Casade Balboa 0 MunicipalGymnasium a MuseumofPhotograph icArts 0 SanD iegoHall of Champions b MuseumofSan Diego History 0 Houseof PacificRelat ionsInternational Cottages c SanDiego Mode l RailroadMuseum d BalboaArt Conservation Cente r C) UnitedNations Bui lding e Committeeof100 G Hallof Nations u f Cafein the Park SpreckelsOrgan Pavilion 4D g SanDiego Historical Society Research Archives 0 JapaneseFriendship Garden u • G) CommunityChristmas Tree G Zoro Garden ~ fI) ReubenH.Fleet Science Center CDPalm Canyon G) Plaza deBalboa and the Bea Evenson Fountain fl G) HouseofCharm a MingeiInternationa l Museum G) SanDiego Natural History Museum I b SanD iegoArt I nstitute (D RoseGarden j t::::J c:::i C) AlcazarGarden (!) DesertGarden G) MoretonBay Ag T ree •........ ••• . I G) SanDiego Museum ofMan (Ca liforniaTower) !il' . .- . WestGate (D PhotographicArts Bui lding ■ • ■ Cl) 8°I .■ m·■ .. •'---- G) CabrilloBridge G) SpanishVillage Art Center 0 ... ■ .■ :-, ■ ■ BalboaPar kCarouse l ■ ■ LawnBowling Greens G 8 Cl) I f) SeftonPlaza G MiniatureRail road aa a Founders'Plaza Cl)San Diego Zoo Entrance b KateSessions Statue G) War MemorialBuil ding fl) MarstonPoint ~ CentroCu lturalde la Raza 6) FireAlarm Building mWorld Beat Cultura l Center t) BalboaClub e BalboaPark Activ ity Center fl) RedwoodBrid geCl ub 6) Veteran'sMuseum and Memo rial Center G MarstonHouse and Garden e SanDiego American Indian Cultural Center andMuseum $ OldG lobeTheatre Comp lex e) SanDiego Museum ofArt 6) Administration BuildingCo urtyard a MayS.