Haiti: Selected Issues and Statistical Appendix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doing Business in Haiti: 2018 Country Commercial Guide for U.S

Doing Business in Haiti: 2018 Country Commercial Guide for U.S. Companies INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT, U.S. & FOREIGN COMMERCIAL SERVICE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE, 2018. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED STATES. Table of Contents Doing Business in Haiti _____________________________________________ 5 Market Overview ________________________________________________________ 5 Market Challenges ______________________________________________________ 8 Market Opportunities ____________________________________________________ 9 Market Entry Strategy __________________________________________________ 11 Political Environment ______________________________________________ 11 Political Environment ___________________________________________________ 11 Selling U.S. Products & Services ____________________________________ 12 Using an Agent to Sell U.S. Products and Services __________________________ 12 Establishing an Office __________________________________________________ 12 Franchising ___________________________________________________________ 13 Direct Marketing _______________________________________________________ 13 Haiti Country Commercial Guide, June 2018 2 Joint Ventures/Licensing ________________________________________________ 13 Selling to the Government _______________________________________________ 13 Distribution & Sales Channels ___________________________________________ 14 Express Delivery ______________________________________________________ 15 Selling Factors & Techniques ____________________________________________ -

Haiti Background Report

2008 Haiti Background Report Anthony Diaz, Ashley Trapp, Annie Feldman Lehigh University 2/18/2008 Page 1 of 36 Table of Contents Introduction What is Development? ........................................................................................................................... 2 Values Foundation ................................................................................................................................. 2 Theoretical Foundation ......................................................................................................................... 2 Political Instability in Haiti.................................................................................................................... 3 Haiti’s political instability and regime changes have hindered economic growth by causing the government to be incapable of implementing policies or even lasting long enough to devise economic policies. The amount of regime changes in Haiti over the last few decades were the greatest number in Latin America and South America; Argentina trailed Haiti’s number of regime changes slightly with 50 compared to Haiti’s 66 regime changes. .................................................................................................. 4 Our Definition ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Comparisons ......................................................................................................................................... -

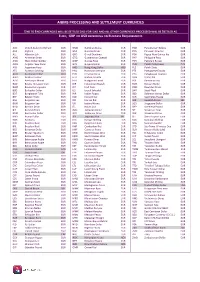

AIBMS Multicurrency List

AIBMS PROCESSING AND SETTLEMENT CURRENCIES END TO END CURRENCIES WILL BE SETTLED LIKE-FOR-LIKE AND ALL OTHER CURRENCIES PROCESSED WILL BE SETTLED AS EURO, GBP OR USD DEPENDING ON BUSINESS REQUIREMENTS AED United Arab Emi Dirham EUR GMD Gambian Dalasi EUR PAB Panamanian Balboa EUR AFA Afghani EUR GNF Guinean Franc EUR PEN Peruvian New Sol EUR ALL Albanian Lek EUR GRD Greek Drachma EUR PGK Papua New Guinea Kia EUR AMD Armenian Dram EUR GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal EUR PHP Philippine Peso EUR ANG West Indian Guilder EUR GWP Guinea Peso EUR PKR Pakistani Rupee EUR AON Angolan New Kwan EUR GYD Guyana Dollar EUR PLN Polish Zloty (new) PLN ARS Argentine Peso EUR HKD Hong Kong Dollar HKD PLZ Polish Zloty EUR ATS Austrian Schilling EUR HNL Honduran Lempira EUR PTE Portuguese Escudo EUR AUD Australian Dollar AUD HRK Croatian Kuna EUR PYG Paraguayan Guarani EUR AWG Aruban Guilder EUR HTG Haitian Gourde EUR QAR Qatar Rial EUR AZM Azerbaijan Manat EUR HUF Hungarian Forint EUR ROL Romanian Leu EUR BAD Bosnia-Herzogovinian EUR IDR Indonesian Rupiah EUR RUB Russian Ruble EUR BAM Bosnia Herzegovina EUR IEP Irish Punt EUR RWF Rwandan Franc EUR BBD Barbados Dollar EUR ILS Israeli Scheckel EUR SAR Saudi Riyal EUR BDT Bangladesh Taka EUR INR Indian Rupee EUR SBD Solomon Islands Dollar EUR BEF Belgian Franc EUR IQD Iraqui Dinar EUR SCR Seychelles Rupee EUR BGL Bulgarian Lev EUR IRR Iranian Rial EUR SEK Swedish Krona SEK BGN Bulgarian Lev EUR ISK Iceland Krona EUR SGD Singapore Dollar EUR BHD Bahrain Dinar EUR ITL Italian Lira EUR SHP St.Helena Pound EUR BIF Burundi -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S. -

The Mission Haiti Inc. Travel Guide

The Mission Haiti Inc. Travel Guide Minneapolis, MN 2018 Copyright © 2018 Mission Haiti Inc. All rights reserved. Mission Haiti Inc., P.O. Box 19401, Minneapolis, MN 55419 Contributors: Shelley Butler & Connie Pelner www.missionhaitiinc.org Mission Haiti Inc., is a 501(c)3 nonprofit. Check us out on Guidestar.org. Cover photo by Britney Stark, used with permission. Disclaimer: The information provided in this book is designed to provide helpful information. This book is not meant to, nor should it be used in place of legal or medical advice from your doctor, the Center for Disease Control, or the U.S. Department of State. The publisher and author are not liable for any damages or negative consequences from any action, application or preparation, to any person using this book. References are provided for informational purposes only and do not constitute endorsement of any websites or other sources. Readers should be aware that the websites listed in this book may change. Before travelling to Haiti, please confer with a doctor and refer to: • U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Dept. of Homeland Security, For International Visitors, Know Before You Visit web page • U.S. Dept. of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, U.S. Passports & International Travel web page • CDC / Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Information for Travelers to Haiti Embassy of the United States, Port au Prince, Haiti In case of emergency, please contact the American Citizen Services office as soon as possible so that we may provide you with assistance. U.S. Embassy Port-au-Prince Open Monday - Friday, 7:00 A.M. -

BIS Locational Banking Statistics: Notes to Explain the Data Structure

Version DSD_LBS_V201712 December 2017 BIS locational banking statistics: explanation of the data structure definitions Contents 1. DSD for reporting: BIS_LBP ........................................................................................... 2 2. Code lists for selected dimensions.................................................................................. 4 2.1. Currency denomination: L_DENOM ...................................................................... 4 2.2. Currency type of reporting country: L_CURR_TYPE ............................................. 6 2.3. Parent country: L_PARENT_CTY .......................................................................... 7 2.4. Reporting country: L_REP_CTY ............................................................................ 9 2.5 Counterparty country dimension: L_CP_COUNTRY ........................................... 11 3. Consistency in reporting ............................................................................................... 18 3.1 Aggregates vs unallocated members .................................................................. 18 3.2 Instrument breakdown ......................................................................................... 18 3.3 Debt securities liabilities ...................................................................................... 18 3.4 Related offices and central banks ........................................................................ 19 3.5 Unrelated banks .................................................................................................. -

Haitian Currency Explained

A HaitiHub Info Packet for everyone committed to a more effective and respectful way of working in Haiti Money Matters (A HaitiHub Info Packet – See www.haitihub.com for more) There are 3 currencies that you will encounter in Haiti: 1) U.S. Dollars, 2) Haitian Gourdes and 3) Haitian Dollars. U.S. Dollars ~ The vast majority of businesses and individuals selling something in Haiti will accept U.S. Dollars. ~ Gourdes may be preferred in places like outdoor markets but U.S. Dollars will most likely not be turned down. ~ Creole speakers will call U.S. Dollars, “Dola Ameriken” or “Dola US” (pronounced “oos”). Haitian Gourdes ~ The Haitian Gourde (HTG) is the official currency of Haiti. ~ Every single coin and paper bill in the country is denominated in Haitian Gourdes. ~ Creole speakers call Gourdes, “Goud” (rhymes fairly closely with the English “mood”). ~ The exchange rate of U.S. Dollars to Gourdes fluctuates with currency markets, but for many years it has been somewhere around: 1 USD = 40 HTG (+/- 5 HTG) Haitian Dollars ~ The Haitian Dollar is a concept ONLY. It doesn’t exist as paper or coin. ~ It is confusing, however, because Haitians will very often talk of prices in Haitian Dollars. ~ 5 Gourdes = 1 Haitian Dollar. This exchange rate is fixed forever. ~ If you exit a tap-tap, for example, and the driver demands “2 Dole,” he means 2 Haitian Dollars, which is 10 Gourdes. ~ Creole speakers will say simply “Dola” when they mean Haitian Dollars. They will specify “Ameriken” or “US” if they mean U.S. Dollars. _______www.haitihub.com______www.facebook.com/haitihub______www.twitter.com/haitihub_______ Big Bills As mentioned, Gourdes are universal and U.S. -

Undata WDI Metadata 2015 01 23.Xlsx

World Development Indicators - Country Notes (Dec 2014) Country Code Country Name Note AFG Afghanistan Afghanistan. Region: South Asia. Income Group: Low income. Lending category: IDA. Currency Unit: Afghan afghani. National accounts base year: 2002/03 Latest population census: 1979. Latest household survey: Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), 2010/11.Special Notes: Fiscal year end: March 20; reporting period for national accounts data: FY (from 2013 are CY). National accounts data are sourced from the IMF and differ from the Central Statistics Organization numbers due to exclusion of the opium economy. ALB Albania Albania. Region: Europe & Central Asia. Income Group: Upper middle income. Lending category: IBRD. Currency Unit: Albanian lek. National accounts base year: Original chained constant price data are rescaled. National accounts reference year: 1996. Latest population census: 2011. Latest household survey: Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), 2008/09. DZA Algeria Algeria. Region: Middle East & North Africa. Income Group: Upper middle income. Lending category: IBRD. Currency Unit: Algerian dinar. National accounts base year: 1980 Latest population census: 2008. Latest household survey: Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), 2012. ASM American Samoa American Samoa. Region: East Asia & Pacific. Income Group: Upper middle income. Currency Unit: U.S. dollar. Latest population census: 2010. ADO Andorra Andorra. Region: Europe & Central Asia. Income Group: High income: nonOECD. Currency Unit: Euro. National accounts base year: 1990 Latest population census: 2011. Population figures compiled from administrative registers.. AGO Angola Angola. Region: Sub-Saharan Africa. Income Group: Upper middle income. Lending category: IBRD. Currency Unit: Angolan kwanza. National accounts base year: 2002 Latest population census: 1970. Latest household survey: Malaria Indicator Survey (MIS), 2011.Special Notes: April 2013 database update: Based on IMF data, national accounts data were revised for 2000 onward; the base year changed to 2002. -

Post-Earthquake Haitian Migration to Latin America

MIDEQ: MIGRATION FOR DEVELOPMENT & EQUALITY OCTOBER 2020 Post-Earthquake Haitian Migration to Latin America WORKING PAPER AUTHOR Interuniversity Institute for Research and Development (INURED) www.mideq.org | MIDEQ South-South Migration Hub 1 HAITIAN MIGRATION TO LATIN AMERICA OCTOBER 2020 Contents Glossary 5 Foreword 7 1. Contextualizing Haiti in the Caribbean and the Americas 8 2. Haiti: A Country of Net Emigration 9 2.1 WOMEN AND SOCIAL INEQUALITY IN HAITI 10 2.2 CONTEMPORARY SYSTEMIC CRISES: ENVIRONMENTAL DISASTERS, COLLAPSE OF GOVERNANCE, SOCIAL FRAGILITY, VIOLENCE AND ‘PEYI LOCK’ [COUNTRY LOCKDOWN] 13 3. Haiti’s Migration History in the Global North and Global South 14 3.1 HAITIAN MIGRATION IN THE GLOBAL NORTH 15 3.1.1 UNITED STATES 15 3.1.2 CANADA 17 3.2 HAITIAN MIGRATION WITHIN THE GLOBAL SOUTH 19 3.2.1 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 19 3.2.2 BRAZIL 21 4. Migration Policy and Development in Haiti 40 4.1 PROTECTING HAITIAN MIGRANTS: OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES 42 www.mideq.org | MIDEQ South-South Migration Hub 2 HAITIAN MIGRATION TO LATIN AMERICA OCTOBER 2020 5. Haiti and Forced Return Migration in the Context of COVID-19 43 5.1 THE GLOBAL PANDEMIC AND REMITTANCE LOSSES IN ORIGIN COUNTRIES 47 6. Conclusion 48 References 50 www.mideq.org | MIDEQ South-South Migration Hub 3 HAITIAN MIGRATION TO LATIN AMERICA OCTOBER 2020 Graphs and Maps GRAPHS Fig 1. Share of U.S. Population by State .................................................................. 17 Fig 2. Haitian Dispersion Throughout the World 1919-1976 ..................................... 18 Fig 3. Undocumented Migrants and Irregular Haitian Migrants from Colombia Detected in the Darién Region (Jan. -

UNITED NATIONS OFFICE at GENEVA Press Release GATT/30 Information Centre 15 August 1951

UNITED NATIONS OFFICE AT GENEVA Press Release GATT/30 Information Centre 15 August 1951 GENERAL AGREEMENT ON TARIFFS AND TRADE Initial Par Value Established for the Haitian Gourde The Contracting Parties to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, after full consultation with the International Monetary- Fund, today announced the establishment of the initial par value for the Haitian gourde at 5 gourdes per United States dollar, the rate proposed by the Government of Haiti in accordance with the provisions of Article II, par.l of the Special Exchange Agreement signed between Haiti and the Contracting Parties. Tho parities for the Haitian gourde in terms of gold and in terms of the United States dollar of the weight and fineness in effect on July 1, 194-4-, are as follows: 0.177734 gram of fine gold per gourde; 175.000 gourdes per troy ounce of fine gold; 5.000u0 gourdes per U.S. dollar; 20.0000 U.S. cents per gourde NOTE OF EXPLANATION FOR PRESS CORRESPONDENTS The main purpose of the GATT is to reduce tariffs and to eliminate other barriers to trade. Eut the value of the reductions can be impaired by a country which resorts to currency practices of various kinds. So it is essential that the contracting parties to GATT should each adhere to certain generally accepted principles of monetary policy, as laid down in the Articles of the International Monetary Fund. But not all of the contracting parties are members of the Fund. Accordingly the GATT provides that any contracting 'party which is not a member of the Fund shall enter into a Special Exchange Agreement with the Contracting Parties (as a whole). -

Foreign Currency Exchange Service Instructions and Enrollment Form

Foreign Currency Exchange Service Instructions and Enrollment Form Company Name: Amount Number: Company Number: LT Number: ➊ Payment Instructions Check the box to receive your payment in connection with the transaction associated with the enclosed Letter of Transmittal in a foreign currency (not in U.S. dollars). Note: The Foreign Currency Exchange Service does not apply to any other types of payments (for example, dividends) issued by the above company (the “Company”), any other company, or American Stock Transfer & Trust Company, LLC (“AST”). ➋ Requested Currency for Payment Refer to the Foreign Currency Codes listed on the enclosed “Foreign Currency Exchange Service” section, and enter the three-letter code of your preferred payment. If the currency you selected is not allowed for the country, or if there are any legal restrictions within the country where your bank is located, we will be unable to enroll you for the Foreign Currency Exchange Service. Please contact your local bank with any questions. ➌ Contact Information Clearly print your email address and phone numbers where you can be reached regarding your enrollment. ➍ Indicate if you wish to receive your proceeds in the form of a check (mailed to the address above), or in the form of a wire transfer. ➎ Sign the Authorization and Return this form along with your Letter of Transmittal Print and sign your name exactly as it appears on your account, and exactly as signed on the Letter of Transmittal. If more than one name is listed, all parties must sign. Your signature authorizes the action and agrees to the terms and conditions detailed in the Foreign Currency Exchange Service Agreement Foreign Currency Exchange Service Enrollment Form ➊ Payment Instructions I wish to receive my payment in foreign currency (non-USD). -

Investopedia's Top 300 Forex Terms

Investopedia’s Top 300 Forex Terms www.investopedia.com Investopedia’s Top 300 Forex Terms Absolute Rate The fixed portion of an interest-rate swap, expressed as a percentage rather than as a premium or a discount to a reference rate. The absolute rate is a combination of the reference rate and the premium or discounted fixed percentage. For example, if the LIBOR is 3% and the fixed interest portion of the swap is at a 7% premium, the absolute rate is 10%. It is sometimes also referred to as an absolute swap yield. Accumulation/Distribution A momentum indicator that attempts to gauge supply and demand by determining whether investors are generally "accumulating" (buying) or "distributing" (selling) a certain stock by identifying divergences between stock price and volume flow. It is calculated using the following formula: Acc/Dist = ((Close – Low) – (High – Close)) / (High – Low) * Period's volume For example, many up days occurring with high volume in a downtrend could signal that the demand for the underlying is starting to increase. In practice, this indicator is used to find situations in which the indicator is heading in the opposite direction as the price. Once this divergence has been identified, the trader will wait to confirm the reversal and make his or her transaction decisions using other technical indicators. ADF In currencies, this is the abbreviation for the Andorran Franc. Advance/Decline Index A technical analysis tool that represents the total difference between the number of advancing and declining security prices. This index is considered one of the best indicators of market movements as a whole.