Businessmen.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leading the Way a PHILOSOPHY - in PROGRESS

1 “The direction in which education starts a man will determine his future life.” —Plato 2 Leading the Way A PHILOSOPHY - IN PROGRESS [ INTRODUCTION \ he doors of our first school opened in 1968 because of the desire to experience firsthand Tthe marvelous thrills and excitement in the world of children. When we began, we had no idea of how our programs would evolve. Our intention was to meet the growing needs of families by integrating daycare and preschool into one program, something that seemed a bit radical back then. Today, with 10 locations and 19 programs, we are the only organization in Northern California providing private education and daycare for children from six weeks to 12 years of age. Of interest to us as founders is the tremendous amount of learning that goes on each year in young children. It has always been exciting for John and I to see all the important loving and guiding experiences of infancy incorporated into the children’s development. We believe we have an opportunity to influence much of what will happen to children as they go through elementary school, junior high school and on into adult life. It also is a real challenge to our staff to provide an environment that will encourage maximum development for children, as positive experiences during the early years lead to much greater success in the future. Through the years, we have faced many challenges. In the beginning, just getting the first school ready to open was quite an endeavor. Inspired by our vision of creating a unique and nurturing place for learning, we rolled up our sleeves and did whatever we could ourselves, disregarding the fact that we had no prior experience in many of the tasks we were about to undertake. -

Minutes of the City Council San José, California

MINUTES OF THE CITY COUNCIL SAN JOSÉ, CALIFORNIA TUESDAY, APRIL 7, 2009 The Council of the City of San José convened in regular session at 9:00 a.m. in the Council Chambers at City Hall. Present: Council Members - Campos, Chu, Constant, Herrera, Kalra, Liccardo, Nguyen, Oliverio, Pyle; Reed. Absent: Council Members - Chirco. (Excused) Upon motion unanimously adopted, Council recessed at 9:02 a.m. to a Closed Session in Room W133, to confer with Legal Counsel with respect to (A) Public Employment/Public Employee Appointment Pursuant to Government Code Section 54957: Department or Agency: Independent Police Auditor; Title: Independent Police Auditor; (B) to confer with Legal Counsel pursuant to Government Code subsection (c) of Section 54956.9 in one (1) matter; (C) to confer with Legal Counsel with respect to anticipated litigation – (Claim Filed): of significant exposure to litigation pursuant to subsection (b) of Section 54956.9 of the Government code: (1) Claimant(s): In re Claim of Hildebrand v City Department of Transportation; (2) Claimant(s): In re Claim of Ghenis v City; (D) to confer with Real Property Designated Representatives pursuant to Government Code Section 54956.8: (1) Property: 95 North Third Street, San José, CA 95113; APN: 467-21-002; Negotiating Parties: Jim Ortbal, Paul Krutko, Neil Stone for the City of San José and Steve Dunn for Legacy Partners; Likely Range of Value of Property: Negotiated price and terms of payment based on appraisal and comparable property values; (E) Conference with Legal Counsel – with respect to existing litigation Pursuant to Government Code Section 54956.9 subsection (a): (1) DAL Properties, et al v. -

Annual Report 2014-2015

Mayor of San Jose Sam Liccardo, Frederick J. Ferrer, CEO of The Health Trust, and Carl Guardino, host of the “CEO show”, with The Health Trust Staff after a live recorded discussion covering a range of health issues from access to health and wellness programs to housing for seniors and the homeless. ANNUAL REPORT 2014-2015 Destination: Home, a program of The Health Trust, in partnership with The Economic Round Table, conducted a cost study revealing the cost of homelessness in Santa Clara County to be $520 million annually. For its ten year anniversary, the Applied Materials Silicon Valley Turkey Trot The FOODBasket was dedicated as the Jerry Larson added The Health Trust as a beneficiary. Proceeds will go toward The Health FOODBasket and received a makeover as a part of the Trust Better Choices, Better Health program. dedication ceremony attended by Supervisor Ken Yeager and numerous community members. The Health Trust awarded a grant to Silicon Valley The Health Trust is 1 of 7 organizations in the country to launch a new Leadership Group Foundation to support the Let’s Move project called the Digital Aging Mastery Program. The DigitalAMP will teach The Health Trust Good. To Go. campaign celebrated the addition of yet Salad Bars to California Schools Campaign, which installs seniors to use interactive tablet technology to connect online with friends another Healthy Cornerstore-- Sidhu Market. and support 20 salad bars in high-need Santa Clara County and family. schools. 118,266 pounds 2,232 of free or low-cost produce was distributed to low- students income families from third grade to high school attended garden education programs taught by the Silicon Valley 118 HealthCorps Health Trust staff` provided services to more than 60,000 people across all 3 of The Health Trust initiatives. -

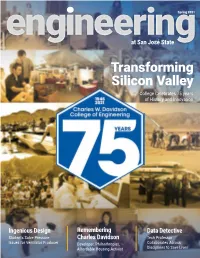

Engineering at San Jose State University, Spring 2021

Spring 2021 at San José State Transforming Silicon Valley College Celebrates 75 years of History and Innovation Ingenious Design Remembering Data Detective Students Solve Pressure Charles Davidson Tech Professor Issues for Ventilator Producer Developer, Philanthropist, Collaborates Across Affordable Housing Activist Disciplines to Save Lives DE A N’ S M E S SAG E TA BLE OF C ON T E N TS In This Issue THIS SPRING, AS BLOSSOMS BLOOM College and Research News and leaves unfurl, our society is slowly 4 re-opening and emerging from the COVID pandemic. 5 Points for Prizes and Career- Preparedness Faculty, lecturers, staff and I are wrestling with big questions: what have we learned from 6 Student-Designed Satellites our pivot to mostly online teaching? What is Assist Scientists on the Ground worth keeping as we go forward to both hybrid and in-person teaching this fall? How will “Our wish is 7 From Flying 20 to Precision 10 engineering colleges look different as a result Flight, and Beyond! of this pandemic and its many, multilayered to continue 16 24 effects on our students, families and Better Every Year: The Bay Area community? What will the workplace be like changing lives 8 for our graduates and how can we help them Biomedical Device Conference to be ready? for the better.” 9 Advancing Concrete Knowledge We are both sober and grateful to present this celebratory issue marking 75 years as and Understanding the College of Engineering at San José State. We have been transforming student lives since 1946, and their success has in turn transformed their families. -

Nomination of Norman Y. Mineta, to Be Secretary of the Department of Transportation

S. HRG. 107–1047 NOMINATION OF NORMAN Y. MINETA, TO BE SECRETARY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JANUARY 24, 2001 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 92–791 PDF WASHINGTON : 2004 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 03-FEB-2003 10:44 May 12, 2004 Jkt 092791 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 D:\DOCS\92791.TXT SSC1 PsN: SSC1 SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona, Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CONRAD BURNS, Montana DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii TRENT LOTT, Mississippi JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine JOHN B. BREAUX, Louisiana SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota GORDON SMITH, Oregon RON WYDEN, Oregon PETER G. FITZGERALD, Illinois MAX CLELAND, Georgia JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada BARBARA BOXER, California GEORGE ALLEN, Virginia JOHN EDWARDS, North Carolina JEAN CARNAHAN, Missouri MARK BUSE, Republican Staff Director ANN CHOINIERE, Republican General Counsel KEVIN D. KAYES, Democratic Staff Director MOSES BOYD, Democratic Chief Counsel (II) VerDate 03-FEB-2003 10:44 May 12, 2004 Jkt 092791 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 D:\DOCS\92791.TXT SSC1 PsN: SSC1 C O N T E N T S Page Hearing held on January 24, 2001 ........................................................................ -

San José Women in the “Feminist Capital, 1975-2006

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Faculty and Staff Publications Library November 2006 Storming Politics: San José Women in the “Feminist Capital, 1975-2006, Danelle L. Moon San Jose State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/lib_pub Part of the Archival Science Commons, History of Gender Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, United States History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Danelle L. Moon. "Storming Politics: San José Women in the “Feminist Capital, 1975-2006," Social Science History Association (2006). This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty and Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Storming Politics: San Jose Women in the “Feminist Capital”, 1975-2006 Danelle Moon San Jose University SSHA Conference November 2006 In this paper I will present some of the results from my oral history project documenting the political experiences of second wave feminists working in Santa Clara County, California. As office holders and social lobbyists, these women directly transformed the political and social fabric of society. Some of these women played a key role as the first recognized political figures in the region, while others worked to document and write about the female experience and built academic programs around feminism and women’s history. Others worked as activists and lobbyists for a variety of causes including the Equal Rights Amendment, the environment, women’s legal rights, and pay equity. -

Argument Against Measure C

ARGUMENT AGAINST MEASURE C Don't be fooled by the misleading description of Measure C. San Jose already allows medical marijuana and has 16 legal dispensaries. In fact, Measure C will repeal controls that protect our neighborhoods and children from the negative impacts of marijuana sales. Measure C would allow dispensaries to open up next to a day care center, a church or a residence. Currently, medical marijuana dispensaries.are prohibited from locating within 150- feet of residences and churches and 1,000 feet from schools, parks, and libraries. This is a good law and should not be changed. Measure C would reduce penalties for selling marijuana to children from thousands of dollars to a $100, slap-on-the-wrist fine. Selling cigarettes or alcohol to a child carries at least a $1000 penalty. A $100 penalty would allow dispensaries to sell marijuana to children with no serious consequences. Measure C would eliminate all guidelines for how marijuana is grown or obtained by the dispensaries. As a result, marijuana grown by drug cartels could be sold in San Jose, as well as marijuana produced in illegal grow-houses, or marijuana manufactured with harmful chemicals. There are 16 marijuana dispensaries in San Jose. Measure C has NO LIMITS on the number of dispensaries that will be allowed to open in San Jose. As a result, we might end up with hundreds of dispensaries throughout the City, making it easy for our children to get marijuana. I Responsible medical marijuana dispensary operators say that Measure C is a trick to eliminate reasonable regulations so that bad operators will be free to sell marijuana to anyone, anytim·e, anywhere. -

San José 2040

Envision San José 2040 GENERAL PLAN Adopted November 1, 2011 As Amended on February 27, 2018 Envision San José 2040 GENERAL PLAN Building a City of Great Places “We are blessed to live in this area with great beauty combined with a robust economy. We must plan carefully for the land remaining under our stewardship so that this good fortune is preserved and enhanced.” E.H. Renzel, Jr., San Jose Mayor 1945-1946 written in the month of his 100th birthday, August 2007 Acknowledgements i ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Mayor and City Council Chuck Reed, Mayor of San Jose Pete Constant, Pierluigi Oliverio, Councilmember District 1 Councilmember District 6 Ash Kalra, Madison Nguyen, Councilmember District 2 Councilmember District 7 Sam Liccardo, Rose Herrera, Councilmember District 3 Councilmember District 8 Kansen Chu, Donald Rocha, Councilmember District 4 Councilmember District 9 Xavier Campos, Nancy Pyle, Councilmember District 5 Councilmember District 10 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Envision Task Force Members Sam Liccardo, Co-Chair Shirley Lewis, Co-Chair David Pandori, Vice-Chair Jackie Adams Dave Fadness Linda J. LeZotte Teresa Alvarado Enrique Fernandez Pierluigi Oliverio Shiloh Ballard Leslee Hamilton Richard Santos Michele Beasley Sam Ho Patricia Sausedo Judy Chirco Nancy Ianni Erik Schoennauer Gary Chronert Lisa Jensen Judy Stabile Pastor Oscar Dace Frank Jesse Neil Struthers Pat Dando Matt Kamkar Alofa Talivaa Harvey Darnell Charles Lauer Michael Van Every Brian Darrow Karl Lee Jim Zito ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Planning Commission Hope Cahan, Chair Edesa Bit-Badal, Vice Chair Ed Abelite Norman Kline Matt Kamkar Christopher Platten Dori L. Yob ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vii viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Envision Community Participants The following community members participated in at least one of the Task Force and community workshops and meetings. -

No. 15-40238 in the UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS

No. 15-40238 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT STATE OF TEXAS, et al. Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al. Defendants-Appellants. On appeal from the United States District Court Southern District of Texas Brownsville Division No. 1:14-cv-00254 (Andrew S. Hanen, J.) BRIEF FOR AMICI CURIAE THE MAYORS OF NEW YORK AND LOS ANGELES, SEVENTY-ONE ADDITIONAL MAYORS, CITIES, COUNTY OFFICIALS, COUNTIES, VILLAGES, AND BOROUGHS, THE UNITED STATES CONFERENCE OF MAYORS, AND THE NATIONAL LEAGUE OF CITIES IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS Zachary W. Carter Michael N. Feuer Corporation Counsel City Attorney 100 Church Street 701 City Hall East New York, NY 10007 200 North Main Street (212) 356-2500 Los Angeles, CA 90012 (212) 356-2509 (f) Attorney for the City of Los Attorney for Bill de Blasio, Angeles, acting by and Mayor of New York through Los Angeles City Mayor Eric Garcetti Jeremy W. Shweder New York Reg. No. 4687927 (Pro hac vice pending) Attorney-in-charge (Additional counsel listed on the signature page) AILA Doc. No. 14122946. (Posted 4/7/15) No. 15-40238 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT STATE OF TEXAS, et al. Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al. Defendants-Appellants. On appeal from the United States District Court Southern District of Texas Brownsville Division No. 1:14-cv-00254 (Andrew S. Hanen, J.) CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS The undersigned counsel of record certifies that the following listed persons and entities as described in the fourth sentence of Rule 28.2.1 have an interest in the outcome of this case. -

Biographical Sketches of the Secretaries of Transportation

Biographical Sketches of the Secretaries of Transportation DOT Historian's Home Page DOT DOT Library Ask DOT Historian About DOT Office of the Biographical Sketches of the Secretaries of Transportation Historian Alan Stephenson Boyd (January 16, 1967-January 20, 1969) A Brief History of the DOT Appointed by Lyndon B. Johnson b. July 20, 1922 Biographical Sketches of the Secretaries of On October 8, 1966, President Lyndon Johnson tasked Alan Stephenson Boyd, Transportation age forty-four, the former Civil Aeronautics Board Chairman and Under Secretary of Commerce for Transportation, with the challenge of setting up the new department. Formerly chairman of the Florida Railroad and Public Utilities Commission, Dates of Service: Boyd headed the Task Force that proposed establishing a Cabinet-level Department, which Secretaries, Deputy Secretaries, and included the Federal Aviation Agency, the Bureau of Public Roads, the United States Coast Heads of Operating Guard, and the Saint Lawrence Seaway Development Corporation, as well as the Great Lakes Administrations Pilotage Association, the Car Service Division of the Interstate Commerce Commission, and the subsidy function of the CAB. During his tenure, the Department issued the first national Chronology of Dates safety and federal motor vehicle standards, and Johnson transferred the Urban Mass Significant to the Origins Transportation Administration from the Department of Housing and Urban Development to and History of the DOT DOT. Boyd subsequently served as the president of the Illinois Central Railroad, the president of Amtrak, and the chairman of Airbus Industrie of North America. Selected Bibliography John Anthony Volpe (January 22, 1969-February 2, 1973) Appointed by Richard M. -

Captain Thomas Fallon of Santa Cruz, San Jose, and San Francisco '

CAPTAIN THOMAS FALLON OF SANTA CRUZ, SAN JOSE, AND SAN FRANCISCO ' a summary of research conducted by Joseph A. King to date, for presentation to the History Aits Advisory Committee of the City of San Jose, California, at a meeting at City Hall on Monday, August 27,1990 by Joseph A. King © copyright 1990 by Joseph A. King, 1161 Nogales St., Lafayette, California 94549. All rights reserved. No pari of this paper may be reproduced except by journalists and reviewers who might want to quote brief passages in a magazine or newspaper. 1 PREFACE Two years ago I had never heard of Captain Thomas Fallon. It was while doing research for a chapter in a book about Irish immigration to Canada and America that I first came across his name. While working on the California chapter, I found that no less than three different "Captain" Fallons had been credited by one source or another with having led a rescue mission to the unfortunate Donner Party, who had experienced terrible tragedy in the snows of the High Sierras during the winter of 1846-47. In attempting to sort out the three historical Captain Fallons, I came across California Cavalier: The Journal of Captain Thomas Fallon, an attractive book by Tom McEnery. It is a fictionalized biography, but it seemed evident that the author had done considerable historical research. There are many footnotes pointing to exact sources of information and, although the author notes that "the Journal is a work of fiction" (Captain Fallon did not actually keep a journal), he also says that it is "as firmly based on an exploration of Thomas Fallon’s life and personal letters as possible." Nevertheless, I had questions about some of the adventures involving historical events that McEnery had credited to Captain Thomas Fallon. -

Mayor's Gang Prevention Task Force

Mayor’s Gang Prevention Task Force Strategic 2018- Work Plan 2020 Trauma to Triumph II A Plan to Foster Hope and Break the Cycle of Youth Violence DRAFT April 2018 Not for distribution The City of San José’s Department of Parks, Recreation and Neighborhood Services would like to acknowledge all the contributions of those who participated in the development of the Mayor’s Gang Prevention Task Force 2018-2020 Strategic Work Plan. THE MAYOR’S STRATEGIC WORK PLAN EXECUTIVE STEERING COMMITTEE: Paul Pereira, Office of Mayor Sam Liccardo, Policy Advisor for Safety Angel Rios, Jr., Director, Parks, Recreation, and Neighborhood Services Matt Cano, Assistant Director, Parks, Recreation, and Neighborhood Services Kip Harkness, Deputy City Manager, Parks, Recreation, and Neighborhood Services Chief Eddie Garcia, Police Chief, San José Police Department Assistant Chief Dave Knopf, Assistant Police Chief, San José Police Department Andrea Flores-Shelton, Injury & Violence Prevention Program, Santa Clara County Public Health THE MAYOR’S STRATEGIC WORK PLAN DEVELOPMENT TEAM: Mario Maciel, Division Manager, Mayor’s Gang Prevention Task Force Angel Rios, Jr., Director, Parks, Recreation, and Neighborhood Services Neil Rufino, Deputy Director, Parks, Recreation, and Neighborhood Services Olympia Williams, Community Services Supervisor, Mayor’s Gang Prevention Task Force CJ Ryan, Program Manager, Parks, Recreation and Neighborhood Services Lt. Greg Lombardo, San José Police Department Ron Soto, Consultant to the Mayor’s Gang Prevention Task Force Trauma to Triumph II 1 The Mayor’s Gang Prevention Task Force (MGPTF) is the Contents City of San José’s Youth Violence Reduction Strategy. Over the past 26 years, the MGPTF has strategically MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR OF SAN JOSÉ .................