Minority and Majority Concerns About Institutional Religious Liberty in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

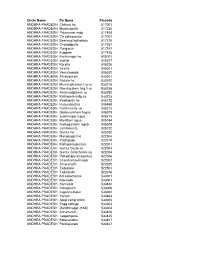

Post Offices

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

Pathanamthitta

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-A SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA 2 CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Village and Town Directory PATHANAMTHITTA Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala 3 MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. 4 CONTENTS Pages 1. Foreword 7 2. Preface 9 3. Acknowledgements 11 4. History and scope of the District Census Handbook 13 5. Brief history of the district 15 6. Analytical Note 17 Village and Town Directory 105 Brief Note on Village and Town Directory 7. Section I - Village Directory (a) List of Villages merged in towns and outgrowths at 2011 Census (b) -

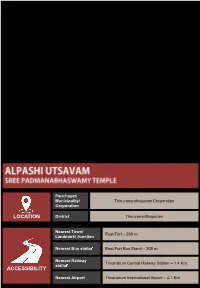

Location Accessibility

Panchayat/ Municipality/ Thiruvananthapuram Corporation Corporation LOCATION District Thiruvananthapuram Nearest Town/ East Fort – 200 m Landmark/ Junction Nearest Bus statio East Fort Bus Stand – 200 m Nearest Railway Trivandrum Central Railway Station – 1.4 Km statio ACCESSIBILITY Nearest Airport Trivandrum International Airport – 4.1 Km The Executive Officer Mathilakam Office, West Nada Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple East Fort, Thiruvananthapuram -695023 Phone: +91-471-2450233 +91-471-2466830 (Temple) CONTACT +91-471-2464606 (Helpline) Email: [email protected] Website: www.sreepadmanabhaswamytemple.org DATES FREQUENCY DURATION TIME October – November (Thulam) Annual 10 Days ABOUT THE FESTIVAL (Legend/History/Myth) The festival is a ritualistic and colourful celebration at the Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple. Ritualistic circumambulations in different kinds of vehicles called Vahanams are an important part of the festivities. In olden times, idols were carried by elephants, however, the practice was given up after an elephant ran amok. Now, a number of priests carry the idols in special Vahanams placed on their shoulders. Six kinds of vehicles are used for these processions. These are the Simhasana Vahanam (Throne), Anantha Vahanam (Serpent), Kamala Vahanam (Lotus), Pallakku Vahanam (Palanquin), Garuda Vahanam (Garuda) and Indra Vahanam (Gopuram). Of these , the Pallakku and Garuda Vahanas are repeated twice and four times respectively. The Garuda Vahanam is considered as the favourite conveyance of the Lord. The different days on which the Vahanams are taken out for procession are as follows: Simhasana Vahanam, Anantha Vahanam, Kamala Vahanam, Pallakku Vahanam, Garuda Vahanam, Indra Vahanam, Pallakku Vahanam and Garuda Vahanam on the following days. Sree Padmanabhaswamy’s Vahanam is in gold while Narayana Swamy’s and Sree Krishna Swamy’s Vahanas are in silver. -

Cognitive Templates for Religious Concepts: Cross-Cultural Evidence for Recall of Counter-Intuitive Representations

Cognitive Science 25 (2001) 535–564 http://www.elsevier.com/locate/cogsci Cognitive templates for religious concepts: cross-cultural evidence for recall of counter-intuitive representations Pascal Boyera,*, Charles Rambleb aWashington University One, Brookings Drive, St. Louis, MO 63130, USA bWolfson College, Oxford University, Linton Rd, Oxford OX2 6UD, UK Abstract Presents results of free-recall experiments conducted in France, Gabon and Nepal, to test predic- tions of a cognitive model of religious concepts. The world over, these concepts include violations of conceptual expectations at the level of domain knowledge (e.g., about ‘animal’ or ‘artifact’ or ‘person’) rather than at the basic level. In five studies we used narratives to test the hypothesis that domain-level violations are recalled better than other conceptual associations. These studies used material constructed in the same way as religious concepts, but not used in religions familiar to the subjects. Experiments 1 and 2 confirmed a distinctiveness effect for such material. Experiment 3 shows that recall also depends on the possibility to generate inferences from violations of domain expectations. Replications in Gabon (Exp. 4) and Nepal (Exp. 5) showed that recall for domain-level violations is better than for violations of basic-level expectations. Overall sensitivity to violations is similar in different cultures and produces similar recall effects, despite differences in commitment to religious belief, in the range of local religious concepts or in their mode of transmission. However, differences between Gabon and Nepal results suggest that familiarity with some types of domain-level violations may paradoxically make other types more salient. These results suggest that recall effects may account for the recurrent features found in religious concepts from different cultures. -

6427 Hon. Edolphus Towns

May 2, 2000 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 6427 health professionals—the 2 million+ registered In Haryana on April 22, three nuns were at- states like Uttar Pradesh where there have nurses in the United States. tacked by a Hindu fundamentalist. One, Sister been three violent attacks against Christians These outstanding men and women, who Anandi, remains in Holy Family Hospital in se- in the last two weeks. work hard to save lives and maintain the rious condition. No one has been arrested for Madhavrao Scindia, deputy leader of the Congress Party in the Lok Sabha (the lower health of millions of individuals, will celebrate this crime. house of Parliament), said the government National Nurses Week from May 6–12, 2000. The militant Hindu fundamentalists who car- should put a stop to incidents like those re- Registered nurses will be honored by hosting ried out these acts are allies of the Indian gov- ported in Uttar Pradesh and Haryana this or participating in several events such as ral- ernment. The government itself has killed over month. He demanded a response from Home lies, childhood immunizations, community 200,000 Christians in Nagaland, over a quar- Affairs Minister Lal Kishen Advani, who is health screenings, publicity efforts, dinners, re- ter of a million Sikhs, more than 65,000 Kash- considered a friend of most of India’s Hindu ceptions and hospital events. I believe that miri Muslims since 1988, and tens of thou- nationlist groups and is the second most any American who has ever been cared for by sands of others. It holds tens of thousands of powerful man in India after Vajpayee. -

Reportable in the Supreme Court of India Civil

Civil Appeal No. 2732 of 2020 (arising out of SLP(C)No.11295 of 2011) etc. Sri Marthanda Varma (D) Thr. LRs. & Anr. vs. State of Kerala and ors. 1 REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELLATE/CIVIL ORIGINAL/INHERENT JURISDICTION CIVIL APPEAL NO.2732 OF 2020 [Arising Out of Special Leave Petition (C) No.11295 of 2011] SRI MARTHANDA VARMA (D) THR. LRs. & ANR. …Appellants VERSUS STATE OF KERALA & ORS. …Respondents WITH CIVIL APPEAL NO. 2733 OF 2020 [Arising Out of Special Leave Petition (C) No.12361 of 2011] AND WRIT PETITION(C) No.518 OF 2011 AND CONMT. PET.(C) No.493 OF 2019 IN SLP(C) No.12361 OF 2011 Civil Appeal No. 2732 of 2020 (arising out of SLP(C)No.11295 of 2011) etc. Sri Marthanda Varma (D) Thr. LRs. & Anr. vs. State of Kerala and ors. 2 J U D G M E N T Uday Umesh Lalit, J. 1. Leave granted in Special Leave Petition (Civil) No.11295 of 2011 and Special Leave Petition (Civil) No.12361 of 2011. 2. Sree Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma who as Ruler of Covenanting State of Travancore had entered into a Covenant in May 1949 with the Government of India leading to the formation of the United State of Travancore and Cochin, died on 19.07.1991. His younger brother Uthradam Thirunal Marthanda Varma and the Executive Officer of Sri Padmanabhaswamy Temple, Thiruvananthapuram (hereinafter referred to as ‘the Temple’) as appellants 1 and 2 respectively have filed these appeals challenging the judgment and order dated 31.01.2011 passed by the High Court1 in Writ Petition (Civil) No.36487 of 2009 and in Writ Petition (Civil) No.4256 of 2010. -

Attukal Pongala Campaign Strategy

Attukal Pongala Campaign Strategy Attukal Pongala 2019 Attukal Pongala is a 10-day festival celebrated at the Attukal Temple, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India, during which there is a huge gathering of millions of women on the ninth day. This is the lighting of the Pongala hearth (called Pandarayaduppu) placed inside the temple by the chief priest. The festival is marked as the largest annual gathering of 2.5 million women by the Guinness World Records in 2009. This is the earliest Pongala festival in Kerala. This temple is also known by the name Sabarimala of women. Mostly Attukal Pongala falls in the month of March or April. Trivandrum Municipal Corporation successfully implemented green protocol for the third time with the help of the Health Department and Green Army International. The need of Green Pongala About 4 years back the amount of waste collected at the end of Attukal Pongala used to measure around 350 tons. Corporation took steps to spread messages of Green Protocol to the devotees and food distributers more effectively with the help of the Green Army. In 2016 Corporation brought this measure down to about 170 tons. Corporation continued to give out Green Protocol messages and warnings throughout the year. And the measure came down to 85 tons in 2017 and 75 tons in 2018. After the years of reduction in waste, Presently, this year, in 2019 the waste has reduced as much as 65 Tons. The numbers show the reason and need for Green Protocol implementation for festivals. It could be understood that festivals or huge gatherings of people anywhere can bring about a huge amount of wastes in which the mixing of food wastes and other materials makes handling of wastes difficult or literally impossible. -

A Thousand and One Wives: Investigating the Intellectual History of the Exegesis of Verse Q 4:24

A THOUSAND AND ONE WIVES: INVESTIGATING THE INTELLECTUAL HISTORY OF THE EXEGESIS OF VERSE Q 4:24 A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Arabic and Islamic Studies By Roshan Iqbal, M.Phil. Washington, DC July 15, 2015 Copyright 2015 by Roshan Iqbal All Rights Reserved ii A THOUSAND AND ONE WIVES: INVESTIGATING THE INTELLECTUAL HISTORY OF THE EXEGESIS OF VERSE Q 4:24 Roshan Iqbal, M.Phil. Thesis Adviser: Felicitas Opwis, Ph.D. ABSTRACT A Thousand and One Wives: Investigating the Intellectual History of the Exegesis of Verse 4:24 traces the intellectual legacy of the exegesis of Qur’an 4:24, which is used as the proof text for the permissibility of mut’a (temporary marriage). I ask if the use of verse 4.24 for the permissibility of mut’a marriage is justified within the rules and regulations of Qur’anic hermeneutics. I examine twenty Qur’an commentaries, the chronological span of which extends from the first extant commentary to the present day in three major Islamicate languages. I conclude that doctrinal self-identity, rather than strictly philological analyses, shaped the interpretation of this verse. As Western academia’s first comprehensive work concerning the intellectual history of mut’a marriage and sexual ethics, my work illustrates the power of sectarian influences in how scholars have interpreted verse 4:24. My dissertation is the only work in English that includes a plurality of voices from minor schools (Ibadi, Ashari, Zaidi, and Ismaili) largely neglected by Western scholars, alongside major schools, and draws from all available sub-genres of exegesis. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Conversion in the Pluralistic Religious Context of India: a Missiological Study

Conversion in the pluralistic religious context of India: a Missiological study Rev Joel Thattupurakal Mathai BTh, BD, MTh 0000-0001-6197-8748 Thesis submitted for the degree Philosophiae Doctor in Missiology at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University in co-operation with Greenwich School of Theology Promoter: Dr TG Curtis Co-Promoter: Dr JJF Kruger April 2017 Abstract Conversion to Christianity has become a very controversial issue in the current religious and political debate in India. This is due to the foreign image of the church and to its past colonial nexus. In addition, the evangelistic effort of different church traditions based on particular view of conversion, which is the product of its different historical periods shaped by peculiar constellation of events and creeds and therefore not absolute- has become a stumbling block to the church‘s mission as one view of conversion is argued against the another view of conversion in an attempt to show what constitutes real conversion. This results in competitions, cultural obliteration and kaum (closed) mentality of the church. Therefore, the purpose of the dissertation is to show a common biblical understanding of conversion which could serve as a basis for the discourse on the nature of the Indian church and its place in society, as well as the renewal of church life in contemporary India by taking into consideration the missiological challenges (religious pluralism, contextualization, syncretism and cultural challenges) that the church in India is facing in the context of conversion. The dissertation arrives at a theological understanding of conversion in the Indian context and its discussion includes: the multiple religious belonging of Hindu Christians; the dual identity of Hindu Christians; the meaning of baptism and the issue of church membership in Indian context. -

Extensions of Remarks E547 HON. BENNIE G. THOMPSON

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E547 in ongoing assistance missions, and over the The Sons of Confederate Veterans aren't A federal judge ruled in Maryland in Feb- last twelve months Hoosier Guard soldiers and happy. Members have said they might try to ruary 1997 that ``The Confederate battle flag airmen have lent a helping hand in Haiti, Hun- re-introduce the flag image. Bills have been on special Maryland license plates is pro- changed before, they say, although they tected by the First Amendment and cannot gary, Kuwait, Slovakia, and South Korea. The won't say how they plan to do it. be banned.'' extraordinary range of military service being OrÐif the Senate fails to consider any- The SCV got a similar ruling in North performed by the men and women of the Indi- thing but the blank plate with the name of Carolina last December. There, the protest ana National Guard is strong testimony to the the organization on itÐthe SCV may take was less about the flag and more about reliance that is placed on them. the issue to court. whether the organization was actually a We should never forget that while the Indi- They're ready for a gentlemanly battle, ``civic group.'' The SCV took it to court and they say. The Sons of Confederate Veterans won. ana National Guard is responsive to its Fed- In Virginia, said Brag Bowling of Rich- eral mission, it also stands ready to respond was organized in 1896 as an offshoot of the United Confederate Veterans. Today, the mond, legislative liaison for the SCV, ``We're to the call of our Governor for service in sup- mission of the group is to ``preserve the his- exploring all options.