Diamonds Fact Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C H R I S T Y &

C h r i s t y & C ooC Since 1773 History and Legacy by Irra K With special thanks to The Stockport library and hat museum FamilyFamily Six reigns of Royals, and Eight generations of the Christy family have forged the brand of Christys London since it’s foundation by Miller Christy in 1773, 237 years ago Following his apprenticeship to a Hatter in Edinburgh, Miller Christy created a company that would survive for generations, outliving thousands of hat makers across the former British Empire: by 1864 for example there were 53 hatting firms in Stockport alone. Throughout hundreds of years, the factory was still managed by direct descendants of the founder of the Firm ValuesValues 1919 Christys readily registered their own The Christy Collection in Stockport is appreciation testament to the influence the company of workers’ had. At its height, it employed 3000 excellent local people leaving a valuable legacy service < - During World War II, hats were not rationed in order to boost morale, and Christys supported the effort within their family-run company, effectively running it like an extended family Celebrating Victory as well as mourning the fallen at the -> end of World War I Trade MarksTrade Marks The Stockport Collection With business of Christy Papers includes a expanding to 500 page booklet detailing foreign lands, trade marks registered safeguarding around the world at the the insignia in height of the British Empire. all it’s forms These involve registering the full name, letters 'C', it’s became vital – insignia, shape, and colours as we shall see In the early days, < - several variations - > of company marks and insignia were circulated, later consolidating into the Christy crown and heraldry which is now recognised the world over Trade Marks iiiiTrade In many territories, Trade Marks were either disputed or had to be re-registered. -

Accat2013.Pdf

Allens Crowns Tiaras A103 1 1/2" Tall A107 1 3/8" Tall A113 1 1/2" Tall Little Princess Tiara* Small Loop Tiara Princess Tiara* A122 1 5/8" Tall A123 2" Tall A133 1 1/4" Tall Small Heart Tiara Royal Princess Tiara* Looping Tiara A162 2" Tall A350 2" Tall AA240 2 1/2" Tall Fleur Di Lis Mardi Gras Tiara* Spring Tiara† ** Interlocking Loop Tiara B102 1 1/2" Tall B110 1 3/8" Tall B120 1 1/2" Tall Loop Tiara Curls & Loop Tiara Loop Tiara* ** Made from cast metal. † Jewel insert available in multiple colors. * Made from cast metal, capped with genuine Austrian rhinestone crystal by Swarovski™. 2 Allens Crowns B149 2" Tall C100 1 1/2" Tall C102 1 5/8" Tall Valentine's Day Tiara* Little Aztec Tiara* Loops Tiara C103 1 3/4" Tall C104 1 1/2" Tall C112 1 5/8" Tall Peak & Loop Tiara Loops & Heart Tiara Three Loops Tiara C117 1 3/8" Tall C206 1 5/8" Tall C301 1 7/8" Tall Five Loops Tiara Shooting Star Tiara Small Jewel Tiara† C350 3" Tall D109 2" Tall D117 1 5/8" Tall Spring Tiara†** Loops & Pearl Tiara Three Loops with Pearls Tiara ** Made from cast metal. † Jewel insert available in multiple colors. * Made from cast metal, capped with genuine Austrian rhinestone crystal by Swarovski™. 3 Allens Crowns D121 2 1/4" Tall E110 2" Tall E113 3" Tall Teardrop & Loops Tiara Peak Tiara Queen Tiara* F100 1 7/8" Tall G111 2 1/4" Tall G120 2" Tall Heart & Loops Tiara Peaked Heart Tiara Loop Tiara* G127 2 3/8" Tall J100 2" Tall J124 2 5/8" Tall Basketweave Tiara Heart Tiara Elevated Star Tiara J168 2" Tall K100 2 1/4" Tall K101 1 7/8" Tall Stars Tiara* Hearts & Loops Tiara Tie the Knot Tiara * Made from cast metal, capped with genuine Austrian rhinestone crystal by Swarovski™. -

Narration on Ethnic Jewellery of Kerala-Focusing on Design, Inspiration and Morphology of Motifs

Journal of Textile Engineering & Fashion Technology Review Article Open Access Narration on ethnic jewellery of Kerala-focusing on design, inspiration and morphology of motifs Abstract Volume 6 Issue 6 - 2020 Artefacts in the form of Jewellery reflect the essence of the lifestyle of the people who Wendy Yothers,1 Resmi Gangadharan2 create and wear them, both in the historic past and in the living present. They act as the 1Department of Jewellery Design, Fashion Institute of connecting link between our ancestors, our traditions, and our history. Jewellery is used- Technology, USA -both in the past and the present-- to express the social status of the wearer, to mark 2School of Architecture and Planning, Manipal Academy of tribal identity, and to serve as amulets for protection from harm. This paper portrays the Higher Education, Karnataka, India ethnic ornaments of Kerala with insights gained from examples of Jewellery conserved in the Hill Palace Museum and Kerala Folklore Museum, in Cochin, Kerala. Included are Correspondence: Wendy Yothers, Department of Jewellery Thurai Balibandham, Gaurisankara Mala, Veera Srunkhala, Oddyanam, Bead necklaces, Design, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, USA, Nagapadathali and Temple Jewellery. Whenever possible, traditional Jewellery is compared Email with modern examples to illustrate how--though streamlined, traditional designs are still a living element in the Jewellery of Kerala today. Received: October 17, 2020 | Published: December 14, 2020 Keywords: ethnic ornaments, Kerala jewellery, sarpesh, gowrishankara mala, veera srunkhala Introduction Indian cultures have used Jewellery as a strong medium to reflect their rituals. The design motifs depicted on the ornaments of India Every artifact has a story to tell. -

Use and Applications of Draping in Turkey's

USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION DUYGU KOCABA Ş MAY 2010 USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF IZMIR UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS BY DUYGU KOCABA Ş IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENTOF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF DESIGN IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES MAY 2010 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences ...................................................... Prof. Dr. Cengiz Erol Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Design. ...................................................... Prof. Dr. Tevfik Balcıoglu Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adaquate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Design. ...................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen Kipöz Supervisor Examining Committee Members Asst. Prof. Dr. Duygu Ebru Öngen Corsini ..................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Nevbahar Göksel ...................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen Kipöz ...................................................... ii ABSTRACT USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION Kocaba ş, Duygu MDes, Department of Design Studies Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen K İPÖZ May 2010, 157 pages This study includes the investigations of the methodology and applications of draping technique which helps to add creativity and originality with the effects of experimental process during the application. Drapes which have been used in different forms and purposes from past to present are described as an interaction between art and fashion. Drapes which had decorated the sculptures of many sculptors in ancient times and the paintings of many artists in Renaissance period, has been used as draping technique for fashion design with the contributions of Madeleine Vionnet in 20 th century. -

Storage Treasure Auction House (CLICK HERE to OPEN AUCTION)

09/28/21 04:44:04 Storage Treasure Auction House (CLICK HERE TO OPEN AUCTION) Auction Opens: Tue, Nov 27 5:00am PT Auction Closes: Thu, Dec 6 2:00pm PT Lot Title Lot Title 0500 18k Sapphire .38ct 2Diamond .12ct ring (size 9) 0533 Watches 0501 925 Ring size 6 1/2 0534 Watches 0502 925 Chain 0535 Watches 0503 925 Chain 0536 Watches 0504 925 Bracelet 0537 Watches 0505 925 Tiffany company Braceltes 0538 Watch 0506 925 Ring size 7 1/4 0539 Watch 0507 925 Necklace Charms 0540 Watches 0508 925 Chain 0541 Watches 0509 925 Silver Lot 0542 Kenneth Cole Watch 0510 925 Chain 0543 Watches 0511 925 Silver Lot 0544 Pocket Watch (needs repair) 0512 925 Necklace 0545 Pocket Watch 0513 10K Gold Ring Size 7 1/4 0546 Earrings 0514 London Blue Topaz Gemstone 2.42ct 0547 Earrings 0515 Vanity Fair Watch 0548 Earrings 0516 Geneva Watch 0549 Earrings 0517 Watches 0550 Earrings 0518 Jordin Watch 0551 Earrings 0519 Fossil Watch 0552 Earrings 0520 Watches 0553 Necklace 0521 Watches & Face 0554 Necklaces 0522 Necklace 0555 Necklace Charms 0523 Watches 0556 Necklace 0524 Kenneth Cole Watch 0557 Necklaces 0525 Pennington Watch 0558 Belly Dancing Jewelry 0526 Watch 0559 Bracelet 0527 Watches 0560 Horseshoe Necklace 0528 Watches 0561 Beaded Necklaces 0529 Watch Parts 0562 Mixed Jewelry 0530 Watches 0563 Necklace 0531 Watch 0564 Earrings 0532 Watch 0565 Chains 1/6 09/28/21 04:44:04 Lot Title Lot Title 0566 Necklace 0609 Chains 0567 Necklace 0610 Necklace 0568 Necklace 0611 Necklace 0569 Necklace 0612 Bracelets 0570 Necklace 0613 Necklace With Black Hills gold Charms 0571 -

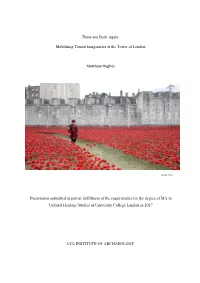

There and Back Again: Mobilising Tourist Imaginaries at the Tower Of

There and Back Again: Mobilising Tourist Imaginaries at the Tower of London Matthew Hughes Ansell 2014 Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MA in Cultural Heritage Studies of University College London in 2017 UCL INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY ‘Those responsible for the brochure had darkly intuited how easily their readers might be turned into prey by photographs whose power insulted the intelligence and contravened any notions of free will: over-exposed photographs of palm trees, clear skies, and white beaches. Readers who would have been capable of skepticism and prudence in other areas of their lives reverted in contact with these elements to a primordial innocence and optimism. The longing provoked by the brochure was an example, at once touching and bathetic, of how projects (and even whole lies) might be influenced by the simplest and most unexamined images of happiness; of how a lengthy and ruinously expensive journey might be set into motion by nothing more than the sight of a photograph of a palm tree gently inclining in a tropical breeze’ (de Botton 2002, 9). 2 Abstract Tourist sites are amalgams of competing and complimentary narratives that dialectically circulate and imbue places with meaning. Widely held tourism narratives, known as tourist imaginaries, are manifestations of ‘shared mental life’ (Leite 2014, 268) by tourists, would-be tourists, and not-yet tourists prior to, during, and after the tourism experience. This dissertation investigates those specific pre-tour understandings that inform tourists’ expectations and understandings of place prior to visiting. Looking specifically at the Tower of London, I employ content and discourse analysis alongside ethnographic field methods to identify the predominant tourist imaginaries of the Tower of London, trace their circulation and reproduction, and ultimately discuss their impact on visitor experience at the Tower. -

Hollands (800) 232-1918 2012 Fine Western Jewelry Since 1936 Fax (325) 653-3963

RETAIL (325) 655-3135 PRICELIST HOLLANDS (800) 232-1918 2012 FINE WESTERN JEWELRY SINCE 1936 FAX (325) 653-3963 Page 2&3 SPUR JEWELRY Regular Junior Spurette Necklace Spurette Earrings 1 3/8" tall 1" tall 5/8" tall 5/8" tall R-P-A $185 J-P-A $185 SN-P-A $160 SE-P-A $ 320 R-P-B 230 J-P-B 230 SN-P-B 190 SE-P-B 380 R-P-C 260 J-P-C 260 SN-P-C 215 SE-P-C 415 R-HC-A 215 J-HC-A 215 SN-HC-A 175 SE-HC-A 350 R-HC-B 260 J-HC-B 260 SN-HC-B 205 SE-HC-B 410 R-HC-C 290 J-HC-C 290 SN-HC-C 230 SE-HC-C 460 R-GO-A 270 J-GO-A 270 SN-GO-A 230 SE-GO-A 460 R-GO-B 320 J-GO-B 320 SN-GO-B 260 SE-GO-B 520 R-GO-C 350 J-GO-C 350 SN-GO-C 290 SE-GO-C 580 R-G-A 1100 J-G-A 900 SN-G-A 625 SE-G-A 1250 R-G-B 1250 J-G-B 1050 SN-G-B 725 SE-G-B 1450 R-G-C 1250 J-G-C 1050 SN-G-C 725 SE-G-C 1450 Spur necklace is price above plus chain. Spur necklace is price above plus chain. Spurette pin is price of spurette necklace plus $35.00. Cufflinks are price above multiplied by two. -

December 16,1886

PORTLAND P !ESS I IAUU. Ill.l) JIM i»J, THURSDAY 1886. ISOB-VI^ 24._ PORTLAND, MORNING, DECEMBER 10, ffltKV/JfWffl PRICE THREE CENTS. OPIC1TAI, NOTICES. MMeBLLANlh. THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS, FROM WASHINGTON. erous dangerous points, and finally madi MCQUADE CONVICTED. FOREICN. Published every day (Sundays excepted) by the this harbor. He was once beaten off by heac MAINE FOLK-LAND. old, had a place, a wife, and Immediate pros- PORTLAND PUBLISHING COMPANY, winds, but when the breeze changed h< pects of a larger family. Exchanoe Street, The Anti-Free Men Erv again attempted to affect an Although the .State has at no At 97 Portland, Me Ship Greatly extrance, ant The Great Trials Comes to a Mos t Cerir to be the Acres Held in Trust for Futuri > present pub- INSURANCE. this time succeeded. iny Beginning Watchful lic lands which It there are or OR. communications to with his cease may sell, eight E. Address all Weary B. at the Outlook. REED. couraged less watch and labor Conclusion. Towns. lie rau the schooner oi Satisfactory cf England’s Movements. MIX! TllOt'SAXD ACRES PORTLAND PUBLISHING CO. the flats and sought sleeo in his berth. Tbt which have and Botanic PRENTISS LORING’S AGENCY. vessel was found the not wholly passed to private Clairvoyant Physician The Bill Not by captain, who hat Story of the Celebrated 1 Likely to Be Considerec reached this Blnghan are have .N1EDICAI. BOOMS MAINE. city and dispatched a tug ir The Jury Agree on a Verdict In Four The r smoval of Chief Secret*..-/ ol parties. -

SCA Circlet of Lordship, Sterling Silver with Amber and Sapphires

Artisan’s Name: Lord Snorri skyti Bjarnarson, MKA David Haldenwang, [email protected] Title of Project: SCA Circlet of Lordship, sterling silver with amber and sapphires Overview: I really like shiny things. I decided I needed more shiny things, but pretty shiny things are extremely expensive. I figured I’d kill two birds with one stone and learn to make more shiny things myself, while saving some money. I chose to make a circlet for myself because it gave me the opportunity to make something particularly visible and gaudy. I used sterling silver, 14k gold, and fine silver, because only thralls wear brass, and chose sapphire and amber cabochons to mount on it, because my arms are Or and Azure. I chose to use seven gems, for the simple reason that seven is not six – I do not want this mistaken for a Baronial coronet. Historical Basis: Some of the earliest forms of headgear worn to denote royalty or nobility are the diadems worn by the ancient Greeksi. These are still preserved in museums, and illustrated on many coins of the era. For example, this coin, of Antiochus III of the Selucid Empire (ca. 223 BC – 187 BC), shows him wearing a diadem, and bears the inscription in Greek ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΑΝΤΙΟΧΟΥ, of King Antiochusii: While these diadems started as simple ribbons or wreaths, worn upon the head for ceremonial or religious reasonsiii, by the 4th century, it was fairly common for rulers in the Greek world to wear a golden wreath on their head as a symbol of nobility or even divinity – because many depictions of the Greek pantheon showed the gods wearing wreaths: Heracles with wreath of white poplar leavesiv: There is also the story of Apollo and the nymph Daphne, from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in which she is pursued by Apollo and turns herself into a laurel tree. -

THE PRINCE of WALES and the DUCHESS of CORNWALL Background Information for Media

THE PRINCE OF WALES AND THE DUCHESS OF CORNWALL Background Information for Media May 2019 Contents Biography .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Seventy Facts for Seventy Years ...................................................................................................... 4 Charities and Patronages ................................................................................................................. 7 Military Affiliations .......................................................................................................................... 8 The Duchess of Cornwall ............................................................................................................ 10 Biography ........................................................................................................................................ 10 Charities and Patronages ............................................................................................................... 10 Military Affiliations ........................................................................................................................ 13 A speech by HRH The Prince of Wales at the "Our Planet" premiere, Natural History Museum, London ...................................................................................................................................... 14 Address by HRH The Prince of Wales at a service to celebrate the contribution -

MINUTES of the 69 MEETING of AYNHO HISTORY SOCIETY HELD at the VILLAGE HALL, AYNHO on WEDNESDAY 25 JUNE 2014 Present

MINUTES OF THE 69th MEETING OF AYNHO HISTORY SOCIETY HELD AT THE VILLAGE HALL, AYNHO ON WEDNESDAY 25th JUNE 2014 Present: - Peter Cole - Secretary. There were apologies from Rupert Clark due to work commitments 1. Chairman and Treasurer's Report In Rupert’s absence Peter reported that Middleton Cheney is holding a photographic exhibition on Saturday 19th July from 2pm to 4.30pm in All Saints Church, entitled “The Village – Then and Now”. There will be about 50 photos of Middleton Cheney taken between 1900 and 1930, accompanied by photos of the same view taken today. 2. Royal Mistresses Roger Powell The talk covers the period from 1509 to the present day, and concentrates on people who were royal mistresses for at least ten years. Indeed one was a mistress for 36 years. In many cases from a psychological point of view she was not just an object of desire but she more or less became a second wife, and sometimes even a mother to the king. The origin of the role in the early days of the Middle Ages derives from the many loveless royal marriages, as for kings the main reason for a marriage was to secure or maintain an alliance to build his empire or strengthen his position against enemies. Once a queen had given the king one or two heirs, he would forget or even abandon her and take a mistress. In England a royal mistress did not become a feature of court society until the 17th century. In France they had been around in the mid-1600s, but it took a while before England followed suit. -

Fine Art, Antiques, Jewellery, Gold & Silver, Porcelain and Quality

Fine Art, Antiques, Jewellery, Gold & Silver, Porcelain and Quality Collectables Day 1 Thursday 12 April 2012 10:00 Gerrards Auctioneers & Valuers St Georges Road St Annes on Sea Lancashire FY8 2AE Gerrards Auctioneers & Valuers (Fine Art, Antiques, Jewellery, Gold & Silver, Porcelain and Quality Collectables Day 1 ) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 Lot: 14 A Russian Silver And Cloisonne 9ct Gold Diamond & Iolite Cluster Enamel Salt. Unusual angled Ring, Fully Hallmarked, Ring Size shape. Finely enamelled in two T. tone blue, green red & white and Estimate: £80.00 - £90.00 with silver gilt interior. Moscow 84 Kokoshnik mark. (1908-1917). Maker probably Henrik Blootenkleper. Also French import mark. Estimate: £100.00 - £150.00 Lot: 15 9ct White Gold Diamond Tennis Lot: 2D Bracelet, Set With Three Rows A Russian 14ct Gold Eastern Of Round Cut Diamonds, Fully Shaped Pendant Cross. 56 mark Hallmarked. & Assay Master RK (in cyrillic). Estimate: £350.00 - £400.00 Maker P.B. Circa 1900. 2" in length. 4 grams. Estimate: £80.00 - £120.00 Lot: 16 9ct Gold Opal And Diamond Stud Lot: 8D Earrings. Pear Shaped Opal With Three Elegant Venetian Glass Diamond Chips. Vases Overlaid In Silver With Estimate: £35.00 - £45.00 Scenes Of Gondolas And Floral Designs. Two in taupe colour and a larger one in green. Estimate: £30.00 - £40.00 Lot: 17 Simulated Pearl Necklace, White Lot: 10 Metal Clasp. Platinum Diamond Stud Earrings, Estimate: £25.00 - £30.00 Cushion Shaped Mounts Set With Princess Cut Diamonds, Fully Hallmarked, As New Condition. Estimate: £350.00 - £400.00 Lot: 18 9ct Gold Sapphire Ring, The Lot: 12 Central Oval Sapphire Between Large 18ct Gold Diamond Cross, Diamond Set Shoulders, Ring Mounted With 41 Round Modern Size M, Unmarked Tests 9ct.