On Ritual Imitation and Embodiment in Orissa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

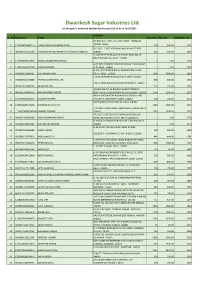

Dwarikesh Sugar Industries Ltd. List of Unpaid / Unclaimed Dividend for the Year 2019-20 As on 31/03/2020

Dwarikesh Sugar Industries Ltd. List of unpaid / unclaimed dividend for the year 2019-20 as on 31/03/2020 FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME LAST NAME ADDRESS FOLIO FOLIO/ DP ID CLIENT ID DIVIDEND AMOUNT PO BOX 3747 SHELL GTL 9TH FLOOR 12032800-00485214- 300.00 CHIRAG PRAVINCHANDRA SHAH MIRQUAB TOWER DOHA 0602321270000152 P.O. BOX - 13027 ABUDHABI ABUDHABI IN300239-14567240- 550.00 GOPAKUMAR PALAMADATHUVASUDEVA MENON OTHERS 10132100012128 T-166 FIST FF NEAR GULATI CHAKKI 12029900-05661905- ROAD NO 20 BALJIT NAGAR New Delhi 2.00 00111000161340 PANKAJ KUMAR SRIVASTAVA 110008 A/67 RESETTLEMENT COLONY KHYALA 12082500-00422908- 1.00 TILAK NAGAR S. O DELHI 110018 603100100005239 BHUVAN VOHRA B-325, SOUTH MOTI BAGH, NANAK IN302269-11080027- 1000.00 CHITRANSHI SAND PURA, DELHI, DELHI, INDIA. 110021 073100100326388 C 20 KIDWAI NAGAR(EAST) DELHI DELHI IN300239-12178458- 500.00 ARVIND KUMAR KHULLAR 110023 9007201006173 J 36 II FLOOR RAJOURI GARDEN NEW IN302236-11096760- 125.00 PAVAN MEHRA DELHI 110027 040104000054269 1/5340 GALI NO 14 BALBIR NAGAR IN300214-19464000- EXTENTION NORTH EAST DELHI 1000.00 7611712117 HARI SHANKER PANDEY SHAHDARA DELHI DELHI 110032 BHOLA NATH NAGAR RAMA BLOCK QTR 12041900-00129504- NO-1900 GALI NO. 5, SHAHADARA DELHI 100.00 13501000005787 NEELAM SHARMA 110032 56 PUNJABI COLONY NARELA DELHI 12033200-05743199- 1250.00 DARSHAN KUMAR HUF 110040 00201110105208 C 29 IIND FLOOR ASHOK VIHAR PHASE 1 12032300-00742101- 1300.00 SHARAD SHARMA DELHI DELHI 110052 0637000104271791 79 C LIG FLATS DDA FLAT MADHUBAN IN300214-20053080- ENCLAVE MADIPUR -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Search a Journal of Arts, Humanities & Management Vol-IX, Issue-1 January, 2015

search A Journal of Arts, Humanities & Management Vol-IX, Issue-1 January, 2015 DDCE Education for All DDCE, UTKAL UNIVERSITY, BHUBANESWAR, INDIA Prof. S. P. Pani, Director,DDCE, Utkal University, Bhubaneswar. Dr. M. R. Behera Lecturer in Oriya, DDCE, Utkal University, Bhubaneswar. Dr. Sujit K. Acharya Lecturer in Business Administration DDCE, Utkal University, Bhubaneswar. Dr. P. P. Panigrahi Executive Editor Lecturer in English, DDCE, Utkal University, Bhubaneswar. ISSN 0974-5416 Copyright : © DDCE, Utkal University, Bhubaneswar Authors bear responsibility for the contents and views expressed by them. Directorate of Distance & Continuing Education, Utkal University does not bear any responsibility. Published by : Director, Directorate of Distance & Continuing Education, Utkal University, Vanivihar, Bhubaneswar – 751007. India. Reach us at E-mail : [email protected]. 91-674 –2376700/2376703(O) Type Setting & Printing: CAD 442, Saheed Nagar Bhubaneswar - 751 007 Ph.: 0674-2544631, 2547731 ii History is TRUTH and TRUTH is God. History is a search for the ultimate truth , an understanding which would end the search for any further explanation. Many of you may feel disturbed with such a content. In fact, many of you may feel this statement to be very subjective. Indeed you may opine that history is all about alternative explanations, choice of one explanation over the others with justification. In this short editorial an attempt is being made to explore, ‘History as Truth’. History like any other discipline can never be dealt in isolation; however, it may seem so. It is not even a distinct part of the whole, it is indeed the whole itself- both temporally and spatially. Why all search in history may be partial yet the partial search always can be of the whole only. -

Dwarikesh Sugar Industries Ltd. List of Unpaid / Unclaimed Dividend for the Year 2018-19 As on 31/03/2021

Dwarikesh Sugar Industries Ltd. List of unpaid / unclaimed dividend for the year 2018-19 as on 31/03/2021 ADDRESS SR. NO. FOLIO_NO NAME HOLDING NET_DIV WARRANT NO. PO BOX 3747 SHELL GTL 9TH FLOOR MIRQUAB TOWER DOHA 1 1203280000485214 CHIRAG PRAVINCHANDRA SHAH . 300 300.00 1261 P.O. BOX - 13027 ABUDHABI ABUDHABI OTHERS 2 IN30023914567240 GOPAKUMAR PALAMADATHU VASUDEVA MENON 100000 550 550.00 1262 T-166 FIST FF NEAR GULATI CHAKKI ROAD NO 20 BALJIT NAGAR New Delhi 110008 3 1202990005661905 PANKAJ KUMAR SRIVASTAVA 2 2.00 1265 A/67 RESETTLEMENT COLONY KHYALA TILAK NAGAR 4 1208250000422908 BHUVAN VOHRA S. O DELHI 110018 1 1.00 1267 B-325, SOUTH MOTI BAGH, NANAK PURA, DELHI, 5 IN30226911080027 CHITRANSHI SAND DELHI, INDIA. 110021 1000 1000.00 1269 C 20 KIDWAI NAGAR(EAST) DELHI DELHI 110023 6 IN30023912178458 ARVIND KUMAR KHULLAR 500 500.00 1270 J 36 II FLOOR RAJOURI GARDEN NEW DELHI 110027 7 IN30223611096760 PAVAN MEHRA 125 125.00 1271 1/5340 GALI NO 14 BALBIR NAGAR EXTENTION 8 IN30021419464000 HARI SHANKER PANDEY NORTH EAST DELHI SHAHDARA DELHI DELHI 110032 1000 1000.00 1273 BHOLA NATH NAGAR RAMA BLOCK QTR NO-1900 9 1204190000129504 NEELAM SHARMA GALI NO. 5, SHAHADARA DELHI 110032 100 100.00 1272 56 PUNJABI COLONY NARELA DELHI 110040 10 1203320005743199 DARSHAN KUMAR HUF 1250 1250.00 1274 C 29 IIND FLOOR ASHOK VIHAR PHASE 1 DELHI DELHI 11 1203230000742100 SHARAD SHARMA 110052 1300 1300.00 1277 79 C LIG FLATS DDA FLAT MADHUBAN ENCLAVE 12 IN30021420053080 VINOD KUMAR MOLPARIA MADIPUR PASCHIM VIHAR NEW DELHI DELHI 1 1.00 1278 D-16/60, SECOND FLOOR, SECTOR-7, ROHINI, DELHI 13 IN30226910669951 DALVINDER DHAWAN 110084 1 1.00 1279 D-10/32 SECTOR-15 ROHINI DELHI 110085 14 IN30078110048169 SAPNA VERMA 200 200.00 1280 362 BLOCK A-2 ROHINI SECTOR - 8 DELHI 110085 15 IN30096610747826 ANJU MANOCHA 444 444.00 1281 C-3/9 PRASHANT VIHAR ABOVE PUNJAB NATIONAL 16 IN30223611000626 TRIPTA MADAN BANK IIIRD FLOOR SEC 13 ROHINI NEW DELHI 1000 1000.00 1282 E -34 PREET VIHAR DELHI 110092 17 IN30167010132793 SAROJ DEVI 10 10.00 1284 A 35 VIKALP APPARTMENTS PLOT NO 92 I.P. -

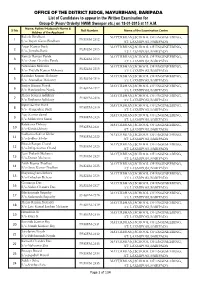

Office of the District Judge, Mayurbhanj, Baripada

OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT JUDGE, MAYURBHANJ, BARIPADA List of Candidates to appear in the Written Examination for Group-D (Peon/ Orderly/ NWM/ Sweeper etc.) on 18-01-2015 at 11 A.M. Name, Father/ Husband's Name & Sl No Roll Number Name of the Examination Centre Address of the Applicant Rakesh Bindhani MAYURBHANJ SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING, 1 PEGEM-2312 S/o- Rajani Kanta Bindhani AT: LAXMIPOSI, BARIPADA ArjunAt-Morada, Kumar P.O./P.S.-Morada, Barik MAYURBHANJ SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING, 2 PEGEM-2313 S/o- Jitendra Barik AT: LAXMIPOSI, BARIPADA SameerAt- Morada, Ranjan P.O./P.S.-Morada, Panda MAYURBHANJ SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING, 3 PEGEM-2314 S/o - Sarat Chandra Panda AT: LAXMIPOSI, BARIPADA NilambaraAt- Madhuban, Mohanta P.O.- Belgachhia MAYURBHANJ SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING, 4 PEGEM-2315 S/o- Prafulla Kumar Mohanta AT: LAXMIPOSI, BARIPADA RabindraAt- Tikayatpur, Kumar P.O.- Mohanty Sankerko MAYURBHANJ SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING, 5 PEGEM-2316 S/o- Srustidhar Mohanty AT: LAXMIPOSI, BARIPADA SanjayAt- Khuruntia, Kumar Nayak P.O- Khuruntia MAYURBHANJ SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING, 6 PEGEM-2317 S/o-Harekrushna Nayak AT: LAXMIPOSI, BARIPADA ManojAt- San Kumar Kholadi, Adhikary P.O.-Bad Kholadi MAYURBHANJ SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING, 7 PEGEM-2318 S/o-Ratikanta Adhikary AT: LAXMIPOSI, BARIPADA SapanAt- Debkumar, Kumar Barik P.O.- Jhariapimpal MAYURBHANJ SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING, 8 PEGEM-2319 S/o- Gangadhar Barik AT: LAXMIPOSI, BARIPADA AjayAt- Chandipur, Kumar Samal P.O.-Ambapua MAYURBHANJ SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING, 9 PEGEM-2320 S/o-Mukteswar Samal AT: LAXMIPOSI, BARIPADA RabikantaAt- Balibil, -

The Life of Krishna Chaitanya

The Life of Krishna Chaitanya first volume of the series: The Life and Teachings of Krishna Chaitanya by Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center (second edition) Copyright © 2016 Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center All rights reserved. ISBN-13: 978-1532745232 ISBN-10: 1532745230 Our Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center is a non-profit organization, dedicated to the research, preservation and propagation of Vedic knowledge and tradition, commonly described as “Hinduism”. Our main work consists in publishing and popularizing, translating and commenting the original scriptures and also texts dealing with history, culture and the peoblems to be tackled to re-establish a correct vision of the original Tradition, overcoming sectarianism and partisan political interests. Anyone who wants to cooperate with the Center is welcome. We also offer technical assistance to authors who wish to publish their own works through the Center or independently. For further information please contact: Mataji Parama Karuna Devi [email protected], [email protected] +91 94373 00906 Contents Introduction 11 Chaitanya's forefathers 15 Early period in Navadvipa 19 Nimai Pandita becomes a famous scholar 23 The meeting with Keshava Kashmiri 27 Haridasa arrives in Navadvipa 30 The journey to Gaya 35 Nimai's transformation in divine love 38 The arrival of Nityananda 43 Advaita Acharya endorses Nimai's mission 47 The meaning of Krishna Consciousness 51 The beginning of the Sankirtana movement 54 Nityananda goes begging -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1789, 20/03/2017 P`Kasana : Baart Sarkar

Trade Marks Journal No: 1789, 20/03/2017 Reg. No. TECH/47-714/MBI/2000 Registered as News Paper P`kaSana : Baart sarkar vyaapar icanh rijasT/I esa.ema.raoD eMTa^p ihla ko pasa paosT Aa^ifsa ko pasa vaDalaa mauMba[- 400037 durBaaYa : 022 24101144 ,24101177 ,24148251 ,24112211. fO@sa : 022 24140808 Published by: The Government of India, Office of The Trade Marks Registry, Baudhik Sampada Bhavan (I.P. Bhavan) Near Antop Hill, Head Post Office, S.M. Road, Mumbai-400037. Tel:022-24140808 1 Trade Marks Journal No: 1789, 20/03/2017 Anauk/maiNaka INDEX AiQakairk saucanaaeM Official Notes vyaapar icanh rijasT/IkrNa kayaa-laya ka AiQakar xao~ Jurisdiction of Offices of the Trade Marks Registry sauiBannata ko baaro maoM rijaYT/ar kao p`arMiBak salaah AaoOr Kaoja ko ilayao inavaodna Preliminary advice by Registrar as to distinctiveness and request for search saMbaw icanh Associated Marks ivaraoQa Opposition ivaiQak p`maaNa p`~ iT.ema.46 pr AnauraoQa Legal Certificate/ Request on Form TM-46 k^apIra[T p`maaNa p`~ Copyright Certificate t%kala kaya- Operation Tatkal saava-jainak saucanaaeM Public Notices svaIkRit ko puva- iva&aipt Aavaodna Applications advertised before acceptance-class-wise: 2 Trade Marks Journal No: 1789, 20/03/2017 vaga- / Class - 1 11-114 vaga- / Class - 2 115-147 vaga- / Class - 3 148-368 vaga- / Class - 4 369-399 vaga- / Class - 5 400-1323 vaga- / Class - 6 1324-1394 vaga- / Class - 7 1395-1496 vaga- / Class - 8 1497-1531 vaga- / Class - 9 1532-1801 vaga- / Class - 10 1802-1847 vaga- / Class - 11 1848-1989 vaga- / Class - 12 1990-2054 -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1877, 26/11/2018 P`Kasana : Baart Sarkar

Trade Marks Journal No: 1877, 26/11/2018 Reg. No. TECH/47-714/MBI/2000 Registered as News Paper p`kaSana : Baart sarkar vyaapar icanh rijasT/I esa.ema.raoD eMTa^p ihla ko pasa paosT Aa^ifsa ko pasa vaDalaa mauMba[- 400037 durBaaYa : 022 24101144 ,24101177 ,24148251 ,24112211. fO@sa : 022 24140808 Published by: The Government of India, Office of The Trade Marks Registry, Baudhik Sampada Bhavan (I.P. Bhavan) Near Antop Hill, Head Post Office, S.M. Road, Mumbai-400037. Tel:022-24140808 1 Trade Marks Journal No: 1877, 26/11/2018 Anauk/maiNaka INDEX AiQakairk saucanaaeM Official Notes vyaapar icanh rijasT/IkrNa kayaa-laya ka AiQakar xao~ Jurisdiction of Offices of the Trade Marks Registry sauiBannata ko baaro maoM rijaYT/ar kao p`arMiBak salaah AaoOr Kaoja ko ilayao inavaodna Preliminary advice by Registrar as to distinctiveness and request for search saMbaw icanh Associated Marks ivaraoQa Opposition ivaiQak p`maaNa p`~ iT.ema.46 pr AnauraoQa Legal Certificate/ Request on Form TM-46 k^apIra[T p`maaNa p`~ Copyright Certificate t%kala kaya- Operation Tatkal saava-jainak saucanaaeM Public Notices iva&aipt Aavaodna Applications advertised class-wise: 2 Trade Marks Journal No: 1877, 26/11/2018 vaga- / Class - 1 11-108 vaga- / Class - 2 109-146 vaga- / Class - 3 147-398 vaga- / Class - 4 399-422 vaga- / Class - 5 423-1354 vaga- / Class - 6 1355-1426 vaga- / Class - 7 1427-1542 vaga- / Class - 8 1543-1562 vaga- / Class - 9 1563-1927 vaga- / Class - 10 1928-1979 vaga- / Class - 11 1980-2129 vaga- / Class - 12 2130-2210 vaga- / Class - 13 2211-2215 -

Odisha State Beverages Corporation Ltd ( a G O V E R N M E N T O F O D I S H a U N D E R T a K I N G )

Odisha State Beverages Corporation Ltd ( A G o v e r n m e n t o f O d i s h a U n d e r t a k i n g ) H.O.- 2nd FLOOR, FORTUNE TOWERS,CHANDRASEKHARPUR, BHUBANESWAR-751023 (ODISHA) E-mail : [email protected], Phone : 0674 -2303972 RETAILER INFORMATION Sl Type of District Name Retailer Name Address Shop Details No. Shop C.O, 120 INFANTRY BATTALION 1 ANGUL (TERITORIAL ARMY) BBSR, ANGULCSD EXT COUNTER,ANGUL DEFENCE EXTENSION COUNTER AT ANGUL SATYANANDA DALABEBERA, HOTEL 2 ANGUL DURGA,RAINBROW BRITE TURANGA, HOTEL DURGA,TURANGA,ANGUL ON SHOP HOTEL ANGUL SATYA RANJAN SAMANTA, 3 ANGUL HOTEL ARYA, TURANGA ,ANGUL ON SHOP RESTAURANT TURANGA,ANGUL M/S KALINGA GUEST HOUSE & RESORTS(KAMLESH SATYABRATA SWAIN, HOTEL 4 ANGUL CONTINENTAL), INDUSTRIAL AREA HAKIM ON SHOP HOTEL KAMLESH CONTIINNETAL PADA,ANGUL 5 ANGUL NITAN JAISWAL, DERANGA DERANGA OFF SHOP RAMESH CHANDRA SAHOO & BIJAY 6 ANGUL ANGUL TOWN,ANGUL,Ward No.21,Municipality,Angul OFF SHOP KUMAR SAHOO,ANGUL TOWN NO.I RAMESH CHANDRA SAHOO & BIJAY 7 ANGUL CHHENDIPADA, ANGUL OFF SHOP KUMAR SAHOO, CHHENDIPADA RAMESH CHANDRA SAHOO& BIJAY 8 ANGUL SOUTH BALANDA, ANGUL OFF SHOP KUMAR SAHOO, SOUTHBALANDA RAMESH CHANDRA SAHOO& BIJAY 9 ANGUL KUMAR SAHOO,TALCHER NO-IV( HANDIDHUA,ANGUL OFF SHOP HANDIDHUA) PRABHU KUMAR & SITARAM 10 ANGUL BANTALA ,ANGUL OFF SHOP PRADHAN, BANTALA NO.I RAMESH CHANDRA SAHU & BIJAYA 11 ANGUL AT-BAMUR,P.S-KISHORENAGAR,ANGUL OFF SHOP KUMAR SAHU,BAMUR 12 ANGUL BANSIDHAR DEHURY, NISHA NISHA,ANGUL OFF SHOP 13 ANGUL BANSIDHAR DEHURY, KUMANDA KUMANDA,ANGUL OFF SHOP 14 ANGUL JYOTI RANJAN -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1939, 03/02/2020

Trade Marks Journal No: 1939, 03/02/2020 Reg. No. TECH/47-714/MBI/2000 Registered as News Paper p`kaSana : Baart sarkar vyaapar icanh rijasT/I esa.ema.raoD eMTa^p ihla ko pasa paosT Aa^ifsa ko pasa vaDalaa mauMba[mauMba[---- 400037400037400037 durBaaYa : 022 24101144 ,24101177 ,24148251 ,24112211. Published by: The Government of India, Office of The Trade Marks Registry, Baudhik Sampada Bhavan (I.P. Bhavan) Near Antop Hill, Head Post Office, S.M. Road, Mumbai-400037. Tel: 022 24101144, 24101177, 24148251, 24112211. 1 Trade Marks Journal No: 1939, 03/02/2020 Anauk/maiNakaAnauk/maiNakaAnauk/maiNaka INDEX AiQakairk saucanaaeM Official Notes vyaapar icanh rijasT/IkrNa kayaakayaa----layalaya ka AiQakar xao~ Jurisdiction of Offices of the Trade Marks Registry sauiBannata ko baaro maoM rijrijaYT/araYT/ar kao p`arMiBak salaah AaoOr Kaoja ko ilayao inavaodna Preliminary advice by Registrar as to distinctiveness and request for search saMbaw icanhsaMbaw icanh Associated Marks ivaraoQa Opposition ivaiQak p`maaNa p`p`~~ iT.ema.46 pr AnauraoQa Legal Certificate/ Request on Form TM-46 k^apIra[T p`maaNa p`~ Copyright Certificate t%kala kayat%kala kaya-kaya--- Operation Tatkal saavasaavasaava-saava---jainakjainak saucanaaeM Public Notices iva&aipt Aavaodna Applications advertised class-wise: 2 Trade Marks Journal No: 1939, 03/02/2020 vaga- / Class - 1 11-102 vaga- / Class - 2 103-138 vaga- / Class - 3 139-468 vaga- / Class - 4 469-503 vaga- / Class - 5 504-1800 vaga- / Class - 6 1801-1910 vaga- / Class - 7 1911-2111 vaga- / Class - 8 2112-2147 vaga- / -

The Role of Mathas at Puri in the Culture of Lord Jagannath Bhagaban Mahapatra

Orissa Review July - 2008 The Role of Mathas at Puri in the Culture of Lord Jagannath Bhagaban Mahapatra Among the four religious centers of Hindus, who in course of his spiritual conquest of whole namely Badrinath, Ramnath, Dwarikanath, Sri India visited Puri (820 AD) and brought many Jagannath Dham, Puri is regarded as the most reforms in the Jagannath temple. He also important Pitha as Lord Himself has taken his established a Matha at Puri which is known as abode at Srikhtra, Puri in this Kali Yuga. He is Govardhan Matha. The Bhoga Mandap, where omniscient, omnipotent and omnipresent. He is large quantity of Bhoga are generally offered to the only religion. All sects, all beliefs and all Lord to cater the need of devotees was religions have mingled in His introduced by him eternal oblivion. He in the temple. is Lord Jagannath. After Sankar, the Puri is great Vaisnav famous to such an saint from South extent that it is India Acharya regarded as Ramanuja came heaven. It is to Puri during the universally believed reign of that the Jagannath Chodaganga Dham is the Deva. He confluence of all established a religious faiths. The Matha which is precepts of different sects have paid their visits to the holy known as Emar Matha in front of the Lion's Gate, land of Puri and preached their philosophy and Puri. got them involved in the rituals and services of It is also said that Visnuswami established Jagannath temple, and in course of time Jaganath Ballav Matha at Puri which is known as established their Mathas (monasteries). -

View Entire Book

Orissa Review July - 2008 The Four Dhams Jitendra Narayan Patnaik "Dham" means "Abode". There are four dhams Sankaracharya came to Badri and restored the in four directions of India which are believed to ancient Badrinath idol from the Narad Kund and be the abodes of Hindu gods, and the holiest consecrated it in a cave near Tapt Kund. The places of pilgrimage. The four dhams at the four present temple was built by the Garhwal rulers. corners of India symbolize the essential unity of Tapt Kund, the hot water spring with natural India's spiritual traditions and values. To the north curative properties believed to be the abode of is Badrinath, to the west Dwarka, to the south Lord Agni, faces the shrine. The pilgrims take a Rameshwaram and to the east is Puri. Each of holy dip in the Tapt Kund before entering the the four dhams is a citadel of ancient temples and temple. The temple remains closed from October religious monuments, with one most significant to April due to the winter snow, when temple as its distinguishing landmark. temperatures fall to sub-zero degrees. BADRINATH There are four other shrines (dedicated to Badrinath is at a height of 10,400 feet Lord Vishnu) near Badrinath shrine. They are above sea-level in the Garhwal Mountains, a part Yogadhyan Badri, Bhavishya Badri, Bridha Badri of the larger Himalayas, in the state of Uttaranchal. and Adi Badri. Not far from the Badrinath temple Built in early ninth century AD, the Badrinath is the Hemkund Lake. According to legends, temple is one of the most revered Hindu shrines Guru Govind Singh, the tenth Guru of the Sikhs, of India.