04.Kyung-Nam Kim.Hwp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teutonic Mythology: Gods and Goddesses of the Northland

TTeeuuttoonniicc MMyytthhoollooggyy Gods and Goddesses of the Northland by Viktor Rydberg IN THREE VOLUMES Vol. II NORRŒNA SOCIETY LONDON - COPENHAGEN - STOCKHOLM - BERLIN - NEW YORK 1907 TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME II 53. Myth in Regard to the Lower World — 353 54. Myth Concerning Mimer’s Grove — 379 55. Mimer’s Grove and Regeneration of the World — 389 56. Gylfaginning’s Cosmography — 395 57. The Word Hel in Linguistic Usage — 406 58. The Word Hel in Vegtamskvida and in Vafthrudnersmal — 410 59. Border Mountain Between Hel and Nifelhel — 414 60. Description of Nifelhel — 426 61. Who the Inhabitants of Hel are — 440 62. The Classes of Beings in Hel — 445 63. The Kingdom of Death — 447 64. Valkyries, Psycho-messengers of Diseases — 457 65. The Way of Those who Fall by the Sword — 462 66. Risting with the Spear-point — 472 67. Loke’s Daughter, Hel — 476 68. Way to Hades Common to the Dead — 482 69. The Doom of the Dead — 485 70. Speech-Runes Ords Tírr Námæli — 490 71. The Looks of the Thingstead — 505 72. The Hades Drink — 514 73. The Hades Horn Embellished with Serpents — 521 74. The Lot of the Blessed — 528 75. Arrival at the Na-gates — 531 76. The Places of Punishment — 534 77. The Hall in Nastrands — 540 78. Loke’s Cave of Punishment — 552 79. The Great World-Mill — 565 80. The World-Mill — 568 81. The World-Mill makes the Constellations Revolve — 579 82. Origin of the Sacred Fire — 586 83. Mundilfore’s Identity with Lodur — 601 84. Nat, Mother of the Gods — 608 85. -

Heroic Domains of Ysgard

Codex of the Infinite Planes Volume XXVI: Heroic Domains of Ysgard TheSample Essential Guide to the Planes offile Existence Codex of the Infinite Planes The Essential Guide to the Planes of Existence Volume XXVI: Heroic Domains of Ysgard Written & Designed by “Weird Dave” Coulson DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, the dragon ampersand, Player’s Handbook, Monster Manual, Dungeon Master’s Guide, D&D Adventurers League, all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast in the USA and other countries. All characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any repro- duction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of SampleWizards of the Coast. file ©2016 Wizards of the Coast LLC, PO Box 707, Renton, WA 98057-0707, USA. Manufactured by Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 4 The Square, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1ET, UK. Volume XXVI: Heroic Ysgard as their final reward. The most numerous residents are the vanir, who have built a strong warrior culture in Domains of Ysgard grand feasthalls, honoring a legion of powers known as the Aesir. The Aesir are immensely powerful but supremely “Shouts, songs, and the ringing of steel resound across petty gods that include Odin, Frigg, Thor, and Balder. They the rugged realms of Ysgard, a plane of thrilling victory, mettle constantly in the affairs of the vanir and wage wars agonizing defeat, and little in between. -

Old Norse Elements in the Work of JRR Tolkien

Old Norse elements in the work of J.R.R. Tolkien by Martin Wettstein When John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was 23 Years old, he had already learned Greek, Latin, Anglo Saxon, Old English, Finnish, Welsh and Gothic and had already invented two own languages, called Nevbosh and Qenya. Together with his interest in languages there came up an interest in myths and legends of the countries behind these languages and he read eagerly all the old legends he came across. During these studies he became aware of the fact that England itself had no own mythology. There was the Celtic, the Roman, the Norse and the Christian Mythology but none especially of England. The awareness of this fact and the lack of a mythology behind his own language, Qenya, made him write poems and short stories that told of events and persons as could have taken place in an English mythology. In the invention of these stories he was inspired by the Bible, the Edda [17][18], Celtic Tales, Fairy stories and the pieces of William Shakespeare, just to name the most important sources. In this Essay I would like to focus on the Norse elements that served as sources for the ideas of Tolkien. It is not the aim of this Essay to compare each idea Tolkien had with similar elements in the Norse Mythology. there are already more than enough articles on the ring as Norse element and the attempt to apply Odin to almost each of the Ainur or Tom Bombadil. It shall simply give an idea about how much this mythology served Tolkien as a source of inspiration. -

Norse Mythology I

Norse Mythology I Waldorf Curriculum www.waldorfcurriculum.com © 2007 Booklist Main Text Gods & Heroes from Viking Mythology. Brian Branston. Supplemental Activities Painting book: Painting in Waldorf Education. Dick Bruin and Attie Lichthart. Modeling book: Learning About the World through Modeling. Arthur Auer. Form Drawing book: Creative Form Drawing: Workbook 2. Rudolf Kutzli. Handwork book: Making Magical Fairy-Tale Puppets. Christel Dhom. Eurythmy book: Come Unto These Yellow Sands. Molly von Heider. Parent Background A Path of Discovery: Volume 4. Eric Fairman. The Prose Edda: Tales from Norse Mythology. (the translation recommended in Come Unto These Yellow Sands is the one by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur) The Norse Stories and their Significance. Roy Wilkinson. Suggested Read-Alouds The Wonderful Adventures of Nils. Selma Lagerlöf. The Best Bad Thing. Yoshiko Uchida. Hitty: Her First Hundred Years. Rachel Field. Norse Mythology Unit Introduction Norse Mythology I and Norse Mythology II are both four week long units (that is, 20 days each). The anthology of legends, Gods & Heroes from Viking Mythology, contains 28 stories. Therefore you should plan to cover 14 stories in each of the 20 day units. The outline of Norse Mythology II is included here so that you can see how the stories unfold. The entire content of the anthology is used. Please find this book by Brian Branston – I have looked at other collections of Norse myths and this one is by far the most superior. The basic unit structure is that you will tell (that is, read or tell from memory) a story on the first day. On the second day, the child will be asked to retell the story and you will explore it further – in composition (by adding it to the main lesson book), art (a main lesson book illustration or a modeling exercise), or drama (acting out the legend). -

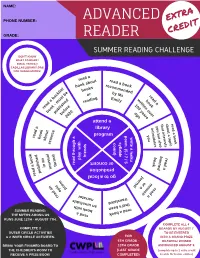

Advanced Reader Challenge Board Extra Credit

NAME: tra PHONE NUMBER: ex ADVANCED it cred GRADE: READER SUMMER READING CHALLENGE DON'T KNOW WHAT TO READ? EMAIL TEENS@ CADILLACLIBRARY.ORG FOR SUGGESTIONS! a read out read k ab a bo boo reco ok t ks mm s oo en li b ded k e by c b or M r a t s e b s ng Em w a a u d adi ily b d m e re ri o a d h t o a - s 1 te k e k li e 0 n r o r 0 o b o y o b u f 0 e v p e 2 a a e b 0 g r r 2 o s attend a a r t e h b y a a o a i o library n d t u u t k t i d e i t a n u m b a o c a y t program p u b o e e o n i w o d t o r o t a r o b b e u a a e o i r a e p i h c s t l s k m c t e s i h t y c e s g t o s o s s i . l u u l a d ( a w o 5 n n r b h t e / h l a y ) i l e t t k 7 r b i a d a k b a f l r o d a e / u e u o p n n o m a h t r e c n o c r o 5 s a o a r n b e s d u k i o r e l n f n a i a d n o i t c u d o r b p u d u a p e l a c o l a o t o g r j o u r n o m m a r e l e a c o i n r m e p a p a o e d d i r a a r e o t a r r r t r a a n n s e l a l t b e a d i l e r t h n a u t ' s n a b h e t e i n w r k e o a o d b a b o o a SUMMER READING: k d a e THE MYTHS AMONG US r RUNS JUNE 12TH - AUGUST 7TH. -

CT CODEG 2017 2 14.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE TECNOLÓGICA FEDERAL DO PARANÁ DEPARTAMENTO ACADÊMICO DE DESENHO INDUSTRIAL TECNOLOGIA EM DESIGN GRÁFICO HENRIQUE NELSON DA SILVA VANIN PROJETO GRÁFICO DE LIVRO COM ILUSTRAÇÕES “EDDAS: O MITO NÓRDICO DA CRIAÇÃO” TRABALHO DE CONCLUSÃO DE CURSO CURITIBA 2017 2 HENRIQUE NELSON DA SILVA VANIN PROJETO GRÁFICO DE LIVRO COM ILUSTRAÇÕES “EDDAS: O MITO NÓRDICO DA CRIAÇÃO” Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso de graduação, apresentado à disciplina de Trabalho de Diplomação, do Curso Superior de Tecnologia em Design Gráfico do Departamento Acadêmico de Desenho Industrial – DADIN – da Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná – UTFPR, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Tecnólogo. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Luciano Henrique Ferreira da Si lva. CURITIBA 2017 Ministério da Educação Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná PR Câmpus Curitiba UNIVERSIDADE TECNOLÓGICA FEDERAL DO PARANÁ Diretoria de Graduação e Educação Profissional Departamento Acadêmico de Desenho Industrial TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO TRABALHO DE CONCLUSÃO DE CURSO 050 PROJETO GRÁFICO DE LIVRO COM ILUSTRAÇÕES “EDDAS: O MITO NÓRDICO DA CRIAÇÃO” por Henrique Nelson da Silva Vanin – 1612573 Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso apresentado no dia 30 de novembro de 2017 como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de TECNÓLOGO EM DESIGN GRÁFICO, do Curso Superior de Tecnologia em Design Gráfico, do Departamento Acadêmico de Desenho Industrial, da Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná. O aluno foi arguido pela Banca Examinadora composta pelos professores abaixo, que após deliberação, consideraram o trabalho aprovado. Banca Examinadora: Prof. Ed Marcos Sarro (Dr.) Avaliador DADIN – UTFPR Prof. Rodrigo André da Costa Graça (MSc.) Convidado DADIN – UTFPR Prof. Luciano Henrique Ferreira da Silva (Dr.) Orientador DADIN – UTFPR Prof. -

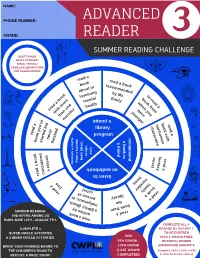

2021 Advanced Reader Boards

NAME: PHONE NUMBER: ADVANCED GRADE: READER SUMMER READING CHALLENGE DON'T KNOW WHAT TO READ? EMAIL TEENS@ CADILLACLIBRARY.ORG FOR SUGGESTIONS! ad a re re k ad a boo boo r reco k ut o mm abo ende ing by d k olv Ms r o inv e o al E b -r b e nt mil o e r me y w o a a o h h k d d m e ealt e f a a n h n ro re th o r w m i n o y e y w a t o r o h ra u e u t r n a g n e e attend a r v t b ' n r a u c o e u o o a d b library h n o k d a r d a y d h e e e r e u w a r k v a t h program c m i o r e s r t i t a e h o n e e a a t e n n t c , n b i a r s i f e b s r o w c f , o o a m s r t r v ) i o ! p e a d a l m ( f c k n u t e t e k a c e d t d k a o s o n f c n e a e i o m o d r r r o n e s o b o c r e v a s f t e b a d r e d a i l s a l s k o o b o i d u a n c a a y n d a a o o t n e t s i e l c r l o m v e e s m f e a b m n a b i e z o i r d l y o a r color) k e e r a l a i b d r a r y a person of person t h e b indigenous, or indigenous, o o k f r o m a BIPOC (Black, BIPOC a r e a d a written by written SUMMER READING: THE MYTHS AMONG US RUNS JUNE 12TH - AUGUST 7TH. -

Thor: Goddess of Thunder Vol

THOR: GODDESS OF THUNDER VOL. 1 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jason Aaron,Russell Dauterman | 116 pages | 13 May 2015 | Panini Publishing Ltd | 9781846536564 | English | Tunbridge Wells, United Kingdom Thor: Goddess of Thunder Vol. 1 PDF Book Part of the " Godbomb " story arc. Maybe even a title of her own? Many millennia from the present, a broken down, old Thor with one eye and one arm sits on the throne of an empty Asgard. Sep 27, sassafrass rated it really liked it Shelves: comics. Community Reviews. Thor tells them that he head belongs to a slain god. Books by Jason Aaron. Clad in armor of living darkness and wielding two Mjolnirs, Thor the Avenger speaks in a distorted voice and tells Gorr that his dark weapon has a name - All-Black the Necrosword - and that it mocks him for thinking he - originally a mere mortal - could unleash its full power when it's meant to be wielded by a god. You can still enjoy it, which is a relief. Thor has become unworthy of lifting his own hammer because somebody whispered something to him. Give Thor his hammer back and give us a genuine female hero, or put in the slightest effort to develope the ones you've already got. Look Jason Aaron has been the master of Thor for a few years now and props to him for creating some awesome stories. His continued work on Black Panther also included a tie-in to the company-wide crossover storyline along with a "Secret Invasion" with David Lapham in Odin's a dick but when is he not? More like 3. -

Thor: Ragnarok

THOR: RAGNAROK Written by Eric Pearson and Craig Kyle & Christopher L. Yost Marvel Studios All rights reserved. Copyright © 2015 Marvel Studios, LLC. No portion of this script may be performed, published, reproduced, sold or distributed by any means, or quoted or published in any medium, including any website, without the prior written consent of Marvel Studios, LLC. Disposal of this script copy does not alter any of the restrictions set forth above. 1 OMITTED 1 A2 OMITTED A2 A3 THE MARVEL LOGO. SMOLDERING, BEGINNING TO TURN ORANGE IN THE A3 HEAT AS WE TILT UP TO SEE- -FIRE. NOTHING BUT FIRE. 2 INT. TIGHT SPACE - INDETERMINATE TIME 2 Dark and cramped. The soft red light of fire seeps through iron slats. Inside this cage is a man, bound by chains. It’s THOR. His beard is long and his clothes are worn. That rough, grizzled look of a man who’s spent years on the road. He awakens with a JOLT. Looks around. THOR Now I know what you’re thinking. Oh no! Thor’s in a cage. How did this happen? (then:) Well, sometimes you have to get captured just to get a straight answer out of somebody. It’s a long story but basically I'm a bit of a hero. See, I spent some time on earth, fought some robots, saved the planet a couple of times. Then I went searching through the cosmos for some magic, colorful Infinity Stone things... didn’t find any. That’s when I came across a path of death and destruction which led me all the way here into this cage.. -

Freehold Cosmology

Freehold Cosmology The Heathen cosmos is centred around the World-Tree, called Yggdrasil by the Norse, that contains all the various realms. There are realms existing in the branches of the World-Tree, around where it meets the Earth, as well as within its roots. This roughly divides the realms into Upper-Worlds, Middle-Worlds, and Lower-Worlds. Within the branches of the World-Tree are the realms of Asgard, Vanaheim, and Alfheim; these realms are associated with the gods and elves. Around the base of the World-Tree are Midgard, Jotunheim, and Svartalfheim; associated with humans, giants, and dwarves respectively. Then within the roots of the World-Tree are Helheim, Muspelheim, and Niflheim; the realms of the dead, fire, and ice respectively. Asgard Asgard is the realm of the Æsir, and as such is home to most of the gods. It is here that the Bifrost (rainbow bridge) connects with Midgard, allowing direct travel for those who know how. Filled with the halls of the various gods, Asgard is a peaceful realm where the gods go about the business of governing the universe. It is in this realm that the gods gather in their Thing at Iðavoll field. One of the three wells that water Yggdrasil’s roots is in Asgard, the Well of Wyrd. Vanaheim Vanaheim is the realm of the Vanir, this is the original home of Njord, Freya, and Ingui- Frey. Very little is known about Vanaheim, and it remains largely a mystery to us. Little is recorded in the myths about Vanaheim, some theorise it to be in the western branches of Yggdrasil. -

Norse Myths Pronunciation Guide

Norse Myths pronunciation guide Tales of Norse gods and heroes have been passed down in many countries for more than a thousand years. The way many of the names are spelled and pronounced today varies in each country. Here you can see how to pronounce these names in a British English style. For some names, there is a common alternative that roughly matches the Icelandic pronunication. Aegir Eye-ear Grani Grah-nee Aesir Eye-sear Greip Grape Alfheim Alf-haym Grer G’rare Andvari And’vaa-ri Grid rhymes with hid Asgard Ass-guard Grimhild Grim-hill’d Ask Ass-k Gudrun Goo-droon Audumla Ow-doom-lar Gullfaxi Gool-fax-ee Balder Bal (as in balance) - durr Gullinbursti Goo-lin-burst-ee Bergelmir Berg-ell-mere Gullveig Gool-vague Berling Bear-ling Gungnir Goong-near Bestla Bes-tla Gunnar Gun-arr Bifrost Bye-frost or Bee-frost Hati Hat-ee Bor Bore Heimdall Haym-dahl Brisingamen Bree-sing-arm-en Hel rhymes with bell Brokk Brock Hermod Her-modd Brynhild Broon-hill-d Hod rhymes with odd Buri Boo (as in book) - ree Honir Her-near Dag rhymes with bag Hreidmar H’ray-d-marr Draupnir Drope-near Hrungnir H-roong-near Dvalin D’vaa-lin Hugi Hoo-yee Eitri Ay-tree Hymir Hay-mere Elli rhymes with belly Hyrrokkin Hay-roe-keen Embla Em-bler Idunn I (as in idiot) - dunn Fafnir Faff-near Ivaldi or I (as in idiot) - thoon Fenris Fenn-riss Ee-val-dee Fimbulwinter Fimm-bull-vinter Jormungand Your-moon-gand Frey rhymes with play Jotunheim Your-turn-haym Freya rhymes with player Lif Leaf Frigg rhymes with dig Lifthrasir Leaf-thrass-ear Geirrod Gay-rod Logi Lor-gee Gjalp -

Euriskodata Rare Book Series

,*• • THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL I Hi PRESENTED BY Richard J. Richardson Provost 1996-2000 /ff "f>?> * (^ p=r ^ ^ ^ : .- < ECLECTIC SCHOOL READINGS OLD NORSE STORIES BY SARAH POWERS BRADISH i >>*Xc NEW YORK-:-CINCINNATI:CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY Copyright, 1900, by SARAH POWERS B-RADISH. OLD NORSE STORIES. ri. W. P. 3 r WHAT THESE STORIES ARE Many years ago our forefathers, who lived far away in the Northland, thought that everything in the world was controlled by some god or goddess, who had special care of that thing. When spring came they said, " Iduna is waking." In early summer, when grass covered the hill- sides and grain waved in the valleys, they said, " Sif is preparing a plentiful harvest." When thunder clouds rolled across the sky and lightning flashed, they said, "Thor is driving his chariot and throwing his hammer." They were glad when the long, light days of summer came, and said, "" We love Balder the beautiful, Balder the good." But they shrank from the scorching heat of later sum- mer, and said, "We fear the pranks of Loki, the mischief maker." They saw the rainbow, and called it the bridge leading up to the home of the gods. They loved the gods who were kind to them ; and they dreaded the frost giants and storm giants, who were the enemies of gods and men. They prayed to Odin, the All-father, for wisdom and 3 4 protection, because they did not know the name of the one great God. When they gathered around the fireside in long winter evenings, they told tales of giants, dwarfs, and elves ; and talked^ of Sigurd, the prince of the sunlight, who killed the dragon of cold and darkness and waked the dawn maiden.