Poland Under Feminist Eyes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

School Nixes Leasing Agreement with Township

25C The Lowell Volume IS, Issue 2 Serving Lowell Area Readers Since 1893 Wednesday, November 21, 1990 earns The Lowell Ledger's "First Buck Contest" turnout was a.m., bagged the buck at 7:45 a.m. better than voter turnout on election day. On Saturday, Vezino bagged a four-point buck with a Well, not quite, but 10 area hunters did walk through the bow. Ledger d(X)r between 7:30 a.m. and 12:30 p.m. on Wednes- Don Post. Ada. was along the Grand River on the flats, day. when he used one shot from his 16-gauge to drop a seven- The point sizes varied from four to eight-point. The weight point. 160-165 pound buck at 8 a.m. Post, hunting since of the bucks fluctuated from 145-200 pounds and the spreads the age of 14. said the seven is the biggest point size buck on the rack were anywhere from eight to 15 inches. he has ever shot. Lowell's Jack Bartholomew was the first hunter to hag Chuck Pfishner, Lowell, fired his winning shot at 7:50 and drag his buck to the Ledger office at 7:35 a.m. Barth- a.m. east on Four Mile. Using a 12-gauge, Pfishner shot olomew was out of the house by 6 a.m., saw his first buck an eight-point, 145-150 pound buck with a nine-inch spread. at 6:55 and shot it at 7:10. Randy Mclntyre. Lowell, was in Delton when he dropped "When I first saw the buck it was about 100 yards away. -

Rights Guide

Prószyński Media Sp. z o.o. RIGHTS GUIDE CONTACT DETAILS 2018 e-mail: [email protected] Izabela Delesiewicz FOREIGN RIGHTS email: [email protected] ph. +48 22 278 17 35 Prószyński Media Gintrowskiego 28 02-697 Warsaw, Poland www.proszynski.pl www.facebook.com/proszynski www.proszynski.pl INDEKS ANDRYKA DAGMARA, Trąf, trąf misia bela, p. 21 KOŁAKOWSKA AGATA, Pięć minut Raisy, p. 9 CONTENTS BRALCZYK JERZY, 1000 słów, p. 35 KOŁCZEWSKA KATARZYNA, Odzyskać utracone, p. 10 BUDKA SUFLERA, SAWIC JAROSŁAW, Memu miastu KORWIN PIOTROWSKA KAROLINA, Sława, p. 47 FICTION na do widzenia, p. 36 KOWALSKA ALEKSANDRA, Ucieczka, p. 11 LITERARY FICTION, p. 1 BULICZ-KASPRZAK KATARZYNA, Pójdę do jedynej, p. 1 kozioł Marcin, Tajemnica przeklętej harfy, p. 29 CRIME & THRILLER, p. 21 CHAJZER FILIP, CHAJZER ZYGMUNT, Chajzerów dwóch, Krzysztoń Antonina, Przeźroczysty chłopiec, p. 30 poetry, p. 26 p. 37 MAN MATYLDA, Trzeba marzyć, p. 12 CHILDREN AND YOUTH LITERATURE, p. 27 CZAJKOWSKA JADWIGA, Ufać zbyt mocno, p. 2 MISZCZUK JOANNA, Wiara i nadzieja, p. 13 DZIEWULSKI JERZY, PYZIA KRZYSZTOF, MŁYNARSKA pAULINA, Rebel, p. 49 p. 35 NON-FICTION, Jerzy Dziewulski o polskiej policji, p. 38 MORAWSKI IRENEUSZ, PRYZWAN MARIOLA, Tylko FRĄCZYK IZABELLA, Jedną nogą w niebie, p. 3 mnie pogłaszcz…Listy do Heleny Poświatowskiej, p. 48 FRĄCZYK IZABELLA, Koncert cudzych życzeń, p. 3 NIEDŹWIEDZKA MAGDALENA, Maria Skłodowska Curie, FRĄCZYK IZABELLA, Spalone mosty, p. 3 p. 14 GIEDROJĆ MAGDALENA, Księżyc nad Rzymem, p. 4 NIEDŹWIEDZKA MAGDALENA, GORSKY VICTOR, Kameleon, p. 39 Opowieści z angielskiego dworu. Diana, p. 15 GRYGIER MARCIN, Nie myśl, że znikną, p. 22 NIEDŹWIEDZKA MAGDALENA, GRZELA REMIGIUSZ, Bądź moim bogiem, p. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Przegląd -Cz-4 Net-Indd.Indd

pejzaże kultury Urszula Chowaniec Feminism Today, or Re-visiting Polish Feminist Literary Scholarship Since 1990s Almost every time the gendered perspective on a particular issue (so often called oblique- ly the woman’s voice) appears in the media, it is immediately confronted by the almost for- mulaic expression “feminism today,” which suggests instantaneously that feminism is, in fact, a matter of the past, and that if one needs to return to this phenomenon, then it requires some explanation. Such interconnections between gender, women and feminism are a con- stant simplifi cation. The article seeks to elaborate this problem of generalization expressed by such formulas as “feminism today.”1 “Feminism today” is a particular notion, which indeed refers to the long political, social, economic and cultural struggles and transformations for equality between the sexes, but also implies the need for its up-dating. Feminism seems to be constantly asked to supply footnotes as to why the contemporary world might still need it, as though equality had been undeniably achieved. This is the common experience of all researchers and activists who deal with the ques- tioning of the traditional order. Even though the order examined by feminism for over 200 years has been changed almost all over the world to various extents, the level of equal- ity achieved is debatable and may still be improved in all countries. Nevertheless, the word feminism has become an uncomfortable word; hence its usage always requires some justi- fi cation. During the past few years in Britain, attempts to re-defi ne feminism may be noted in various media. -

Westminsterresearch

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Socially inherited memory, gender and the public sphere in Poland. Anna Reading School of Media, Arts and Design This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © The Author, 1996. This is a scanned reproduction of the paper copy held by the University of Westminster library. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Users are permitted to download and/or print one copy for non-commercial private study or research. Further distribution and any use of material from within this archive for profit-making enterprises or for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: (http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] SOCIALLY INHERITED MEMORY, GENDER AND THE PUBLIC SPHERE IN POLAND Anna Reading A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 1996 University of Westminster, London, UK **I have a memory, which is the memory of mother's memory' UNIVERSITY OF WESTMINSTER HARROW IRS CENTRE ABSTRACT More recent theories of the 'revolutions' of 1989 in the societies of Eastern and Central Europe now suggest that the underlying dynamic was continuity rather than disjuncture in terms of social and political relations. Yet such theories fail to explain the nature of and the reasons for this continuity in terms of gender relations in the public sphere. -

10Th European Feminist Research Conference Difference, Diversity, Diffraction: Confronting Hegemonies and Dispossessions

10th European Feminist Research Conference Difference, Diversity, Diffraction: Confronting Hegemonies and Dispossessions 12th - 15th September 2018 Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Germany BOOK OF ABSTRACTS IMPRINT EDITOR Göttingen Diversity Research Institute, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Platz der Göttinger Sieben 3, 37073 Göttingen COORDINATION Göttingen Diversity Research Institute DESIGN AND LAYOUT Rothe Grafik, Georgsmarienhütte © Cover: Judith Groth PRINTING Linden-Druck Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Hannover NOTE Some plenary events are video recorded and pictures may be taken during these occasions. Please notify us, if you do not wish that pictures of you will be published on our website. 2 10th European Feminist Research Conference Difference, Diversity, Diffraction: Confronting Hegemonies and Dispossessions 12th - 15th September 2018 Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Germany BOOK OF ABSTRACTS 10TH EUROPEAN FEMINIST RESEARCH CONFERENCE 3 WELCOME TO THE 10TH EUROPEAN FEMINIST RESEARCH CONFERENCE ”DIFFERENCE, DIVERSITY, DIFFRACTION: WELCOME CONFRONTING HEGEMONIES AND DISPOSSESSIONS”! With the first European Feminist Research Conference (EFRC) in 1991, the EFRC has a tradition of nearly 30 years. During the preceding conferences the EFRC debated and investigated the relationship between Eastern and Western European feminist researchers (Aalborg), technoscience and tech- nology (Graz), mobility as well as the institutionalisation of Women’s, Fem- inist and Gender Studies (Coimbra), borders and policies (Bologna), post-communist -

A Queer Feminist Discursive Investigation

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Imaginaries of Sexual Citizenship in Post-Maidan Ukraine: A Queer Feminist Discursive Investigation Thesis How to cite: Plakhotnik, Olga (2019). Imaginaries of Sexual Citizenship in Post-Maidan Ukraine: A Queer Feminist Discursive Investigation. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2019 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000f515 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Imaginaries of Sexual Citizenship in Post-Maidan Ukraine: A Queer Feminist Discursive Investigation by Olga Plakhotnik Submitted to the Open University, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate in Sociology April 2019 2 Abstract This doctoral project is an investigation of the imaginaries of sexual citizenship in post- Maidan Ukraine. I used a queer feminist discourse analysis method to examine how LGBT+ communities seek to position themselves in relation to hegemonic discourses of state and nationhood. Collecting data from focus group discussions and online forums, I identified the Euromaidan (2013-2014) as a pivotal moment wherein sexual citizenship was intensified as a dynamic process of claims-making and negotiation between LGBT+ communities and the state. -

Cinestudio-Flyer-2020-02-23-04-08

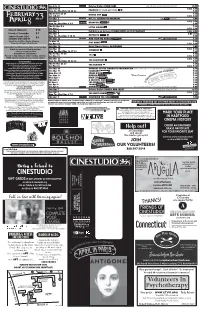

Sun Feb 23 Bolshoi Ballet: SWAN LAKE LIVE PRESENTATION FROM MOSCOW 12:55 Sun Feb 23 4:30, 7:30 Mon Tue Wed Feb 24 25 26 PARASITE in black and white 7:30 Thu Fri Feb 27 28 KNIVES OUT 7:30 Sat Feb 29 2:30, 7:30 Sun Mar 1 NTLive: CYRANO DE BERGERAC ENCORE 1:00 Sun Mar 1 4:30, 7:30 Mon Tue Wed Mar 2 3 4 BEANPOLE 7:30 Thu Fri Mar 5 6 LITTLE WOMEN 7:30 Sat Mar 7 2:30, 7:30 General Admission $10 Sun Mar 8 Exhibition on Screen: LUCIAN FREUD: A SELF PORTRAIT 1:00, 3:00 Friends of Cinestudio $7 Sun Mar 8 5:00 only Mon Tue Wed Mar 9 10 11 MEPHISTO 7:30 Senior Citizens (62+) $8 Students with valid ID Thu Mar 12 AND THEN WE DANCED 7:30 Ticket Prices for NTLive, Bolshoi, Exhibition, Fri Mar 13 7:30 70mm, Special Shows & Benefits vary Sat Mar 14 JUST MERCY 2:30, 7:30 Cinestudio’s boxoffice is now online, so you can buy Sun Mar 15 Royal Opera House: LA BOHÈME 1:00 Sun Mar 15 4:30, 7:30 tickets for any listed show at any time CLEMENCY - online or at the boxoffice. Mon Tue Wed Mar 16 17 18 7:30 DONATING TO CINESTUDIO? Thu Fri Mar 19 20 1917 7:30 You can do that online or at the boxoffice, and now Sat Mar 21 2:30, 7:30 100% of your donation comes to Cinestudio! Sun Mar 22 2:30, 7:30 Mon Tue Wed Mar 23 24 25 THE ASSISTANT 7:30 Thu Fri Mar 26 27 THE TRAITOR 7:30 Sat Mar 28 2:30, 7:30 Sun Mar 29 VOYAGES OF THE CINEMATIC IMAGINATION Silent, with Piano Accompaniment by PATRICK MILLER 2:30 Sun Mar 29 L’ATALANTE 7:30 Mon Mar 30 IMAGE BOOK 7:30 Tue Mar 31 MAKALA 7:30 Wed Apr 1 HIGH LIFE 7:30 Thu Apr 2 A FAITHFUL MAN 7:30 Cinestudio programs are usually listed in -

Liff-2020-Catalogue.Pdf

Welcome Introduction from the LIFF 2020 Team While we greatly miss not presenting LIFF 2020 in venues, we’re delighted to share the line-up on our new streaming platform Leeds Film Player. We return with our regular programme sections for new films – Official Selection, Cinema Versa, Fanomenon, and Leeds Short Film Awards – all curated with the same dedication to diverse filmmaking from the UK and around the world. A huge thank you to everyone who made this transformation to streaming possible and to everyone who helped us plan and prepare for LIFF 2020 being in venues. We hope you enjoy the LIFF 2020 programme from home and we can’t wait to welcome you back to venues for LIFF 2021! Presented by Leading Funders Contents Official Selection 6 Cinema Versa 26 Fanomenon 42 Leeds Short Film Awards 64 Leeds Young Film Festival 138 Indexes 152 Sun Children 2– LIFF 2020 Opening film 3 Team LIFF 2020 LYFF 2020 Team Team Director Director Chris Fell Debbie Maturi Programme Manager Producer Alex King Martin Grund Production Manager Youth Engagement Coordinator Jamie Cross Gage Oxley Film Development Coordinator Youth Programme Coordinator Nick Jones Eleanor Hodson Senior Programmer LYFF Programmers Molly Cowderoy Martin Grund, Eleanor Hodson, Sam Judd Programme Coordinator Alice Duggan Production Coordinator Anna Stopford Programme & Production Assistant Ilkyaz Yagmur Ozkoroglu Virtual Volunteers Lee Bentham, Hannah Booth, Tabitha Burnett, Paul Douglass, Owen Herman, Alice Lassey, Ryan Ninesling, Eleanor Storey, Andrew Young Volunteer Officer Sarah -

Framing Solidarity. Feminist Patriots Opposing the Far Right in Contemporary Poland

Open Cultural Studies 2019; 3: 469-484 Research Article Jennifer Ramme* Framing Solidarity. Feminist Patriots Opposing the Far Right in Contemporary Poland https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2019-0040 Received October 30, 2018; accepted May 30, 2019 Abstract: Due to the attempts to restrict the abortion law in Poland in 2016, we could observe a new broad- based feminist movement emerge. This successful movement became known worldwide through the Black Protests and the massive Polish Women’s Strike that took place in October 2016. While this new movement is impressive in its scope and can be described as one of the most successful opposition movements to the ethno-nationalist right wing and fundamentalist Catholicism, it also deploys a patriotic rhetoric and makes use of national symbols and categories of belonging. Feminism and nationalism in Poland are usually described as in opposition, although that relationship is much more complex and changing. Over decades, a general shift towards right-wing nationalism in Poland has occurred, which, in various ways, has also affected feminist actors and (counter)discourses. It seems that patriotism is used to combat nationalism, which has proved to be a successful strategy. Taking the example of feminist mobilizations and movements in Poland, this paper discusses the (im)possible link between patriotism, nationalism and feminism in order to ask what it means for feminist politics and female solidarity when belonging is framed in different ways. Keywords: framing belonging; social movements; ethno-nationalism; embodied nationalism; public discourse A surprising response to extreme nationalism and religious fundamentalism in Poland appeared in the mass mobilization against a legislative initiative introducing a total ban on abortion in 2016, which culminated in a massive Women’s Strike in October the same year. -

Films Vrijzinnig Bennekom Kopie

FILMS VRIJZINNIG BENNEKOM ABOUT A BOY Regie Paul Weitz Spelers Hugh Grant, Toni ColleFe, Rachel Weisz ADAM’S APPLES regie Anders Thomas Jensen Spelers Ulrich Thomsen, Nicolas Bro, Paprika Steen, Ali Kazim, Mads Mikkelsen A FEW GOOD MEN regie Rob Reiner Spelers Tom Cruise, Jack Nicholson, Demi Moore AKA some of them come true Regie Duncan Roy Spelers MaFhew Leitch, Diana Quick, George Asprey ALL ABOUT MY MOTHER regie Almodóvar Spelers Cecilia Roth, Marisa Paredes, Penelope Cruz,Candela Pena AMADEUS regie Milos Forman Spelers F.Murray, Tom Hulce, Elizabeth Berridge,Jeffrey Jones A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH regie Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger Spelers David Niven, Roger Livesey, Raymond Massey AMELIE Regie Jean- Pierre Jeunet Spelers Audrey Tautou, Mathieu Kassovitz AMOUR regie Michael Haneke Spelers Jean-Louis TrinZgnant, Emmanuelle Riva, Isabelle Huppert AN ANGEL AT MY TABLE regie Jane Campion Spelers Kerry Fox, Alexia Keogh, Karen Fergusson, Iris Churn ANCHE LIBERO VA BENE regie Kim Rossi Stuart Spelers Alessandro Morace, Kim Rossi Stuart, Barbora Bobulova ANKLAGET ACCUSED Regie Jacob Thuesen Spelers Sofie Grabol, Troels Lyby ANNA ZERNIKE , de eerste vrouwelijke predikant Regie Annet Huisman Speler Henny Rinsma A RIVER RUNS THROUGH IT regie Robert Redford Spelers Brad PiF,Craig Sheffer, Tom SkerriF A SINGLE MAN Regie Tom Ford Spelers Colin Firth, Julianne Moore A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE regie Charles Feldman Spelers Vivien Leigh, Marlon Brando A STREETCAT NAMED BOB regie Roger Spo^swoode Spelers James Bowen, Bob the cat ATONEMENT regie