PDF (Full Report)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mr Alan Farrell TD, Dáil Éireann Kildare Street Dublin 2 22Nd February 2018

Bainisteoir Ginearálta Cúram Príomhuil Eagraíocht Cúram Sláinte Pobail Tuaisceart Chathair & Tuaisceart Chontae Bhaile Átha Cliath Saoráid Cúram Sláinte Bhaile Munna Baile Munna, Baile Átha Cliath 9. : 01 8467200 : [email protected] General Manager Primary Care Community Healthcare Organisation Dublin North City & County Ballymun Healthcare Facility Ballymun, Dublin 9. Mr Alan Farrell TD, Dáil Éireann Kildare Street Dublin 2 22nd February 2018 PQ 6101/18 - * To ask the Minister for Health if his department has identified priority areas for primary health care centres in the Fingal area of north county Dublin; and if he will make a statement on the matter. - Alan Farrell. Dear Deputy, The Health Service Executive has been requested to reply directly to you in the context of the above Parliamentary Question which you submitted to the Minister for Health for response. I have examined the matter and the following outlines the position. A National Primary Care Team Accommodation Needs Assessment was carried out in 2012 which was prioritised by the HSE's Primary Care Service on a National basis. The top five priority locations within the Fingal area identified were:- Corduff, Balbriggan, Blanchardstown, Portmarnock and Swords The status of these locations is as follows . Corduff A new Primary Care Centre was constructed and became operational in 2016 . Balbriggan A new Primary Care Centre has been delivered and is operational since the second Quarter of 2017 . Blanchardstown A new Primary Care Centre was delivered and is operational since 2013 . Portmarnock A New Primary Care Centre has been delivered and was operational from Quarter 3 2017 . Swords Is the next highest priority identified within the Fingal Area and the HSE are currently in advanced negotiations with a provider selected to deliver a Primary Care Centre in Swords through the HSE’s Operational Lease Mechanism. -

VA10.5.002 – Simon Mackell

Appeal No. VA10/5/002 AN BINSE LUACHÁLA VALUATION TRIBUNAL AN tACHT LUACHÁLA, 2001 VALUATION ACT, 2001 Simon MacKell APPELLANT and Commissioner of Valuation RESPONDENT RE: Property No. 2195188, Office (over the shop), Unit 3B, Main Street, Ongar Village, County Dublin B E F O R E John Kerr - Chartered Surveyor Deputy Chairperson Veronica Gates - Barrister Member Patrick Riney - FSCS.FIAVI Member JUDGMENT OF THE VALUATION TRIBUNAL ISSUED ON THE 1ST DAY OF DECEMBER, 2010 By Notice of Appeal dated the 2nd day of June, 2010 the appellant appealed against the determination of the Commissioner of Valuation in fixing a valuation of €23,000 on the above relevant property. The Grounds of Appeal are on a separate sheet attached to the Notice of Appeal, a copy of which is attached at the Appendix to this judgment. 2 The appeal proceeded by way of an oral hearing held in the Tribunal Offices on the 18th day of August, 2010. The appellant Mr. Simon MacKell, Managing Director of Ekman Ireland Ltd, represented himself and the respondent was represented by Ms. Deirdre McGennis, BSc (Hons) Real Estate Management, MSc (Hons) Local & Regional Development, MIAVI, a valuer in the Valuation Office. Mr. Joseph McBride, valuer and Team Leader from the Valuation Office was also in attendance. The Tribunal was furnished with submissions in writing on behalf of both parties. Each party, having taken the oath, adopted his/her précis and valuation as their evidence-in-chief. Valuation History The property was the subject of a Revaluation of all rateable properties in the Fingal County Council Area:- • A valuation certificate (proposed) was issued on the 16th June 2009. -

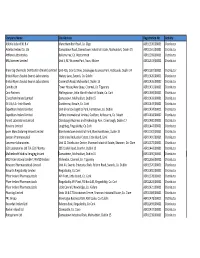

Company Name Site Address Registration No

Company Name Site Address Registration No. Activity AbbVie Ireland NL B.V Manorhamilton Road, Co. Sligo ASR11336/00001 Distributor Astellas Ireland Co. Ltd Damastown Road, Damastown Industrial Estate, Mulhuddart, Dublin 15 ASR11341/00001 Distributor Athlone Laboratories Ballymurray, Co. Roscommon ASR11399/00001 Distributor BNL Sciences Limited Unit S, M7 Business Park, Naas, Kildare ASR11343/00001 Distributor Brenntag Chemicals Distribution (Ireland) Limited Unit 405, Grants Drive, Greenogue Business Park, Rathcoole, Dublin 24 ASR11387/00001 Distributor Bristol‐Myers Squibb Swords Laboratories Watery Lane, Swords, Co. Dublin ASR11426/00001 Distributor Bristol‐Myers Squibb Swords Laboratories Cruiserath Road, Mulhuddart, Dublin 15 ASR11426/00002 Distributor Camida Ltd Tower House, New Quay, Clonmel, Co. Tipperary ASR11431/00001 Distributor Cara Partners Wallingstown, Little Island Industrial Estate, Co. Cork ASR11494/00001 Distributor Clarochem Ireland Limited Damastown, Mulhuddart, Dublin 15 ASR11433/00001 Distributor Eli Lilly S.A ‐ Irish Branch Dunderrow, Kinsale, Co. Cork ASR11449/00001 Distributor Expeditors Ireland Limited Unit 6 Horizon Logistics Park, Harristown, Co. Dublin ASR11434/00001 Distributor Expeditors Ireland Limited Caffery International Limited, Coolfore, Ashbourne, Co. Meath ASR11434/00002 Distributor Forest Laboratories Limited Clonshaugh Business and Technology Park. Clonshaugh, Dublin 17 ASR11400/00001 Distributor Hovione Limited Loughbeg, Ringaskiddy, Co.Cork ASR11447/00001 Distributor Ipsen Manufacturing Ireland -

Blanchardstown Urban Structure Plan Development Strategy and Implementation

BLANCHARDSTOWN DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY URBAN STRUCTURE PLAN AND IMPLEMENTATION VISION, DEVELOPMENT THEMES AND OPPORTUNITIES PLANNING DEPARTMENT SPRING 2007 BLANCHARDSTOWN URBAN STRUCTURE PLAN DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY AND IMPLEMENTATION VISION, DEVELOPMENT THEMES AND OPPORTUNITIES PLANNING DEPARTMENT • SPRING 2007 David O’Connor, County Manager Gilbert Power, Director of Planning Joan Caffrey, Senior Planner BLANCHARDSTOWN URBAN STRUCTURE PLAN E DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY AND IMPLEMENTATION G A 01 SPRING 2007 P Contents Page INTRODUCTION . 2 SECTION 1: OBJECTIVES OF THE BLANCHARDSTOWN URBAN STRUCTURE PLAN – DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 3 BACKGROUND PLANNING TO DATE . 3 VISION STATEMENT AND KEY ISSUES . 5 SECTION 2: DEVELOPMENT THEMES 6 INTRODUCTION . 6 THEME: COMMERCE RETAIL AND SERVICES . 6 THEME: SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY . 8 THEME: TRANSPORT . 9 THEME: LEISURE, RECREATION & AMENITY . 11 THEME: CULTURE . 12 THEME: FAMILY AND COMMUNITY . 13 SECTION 3: DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITIES – ESSENTIAL INFRASTRUCTURAL IMPROVEMENTS 14 SECTION 4: DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY AREAS 15 Area 1: Blanchardstown Town Centre . 16 Area 2: Blanchardstown Village . 19 Area 3: New District Centre at Coolmine, Porterstown, Clonsilla . 21 Area 4: Blanchardstown Institute of Technology and Environs . 24 Area 5: Connolly Memorial Hospital and Environs . 25 Area 6: International Sports Campus at Abbotstown. (O.P.W.) . 26 Area 7: Existing and Proposed District & Neighbourhood Centres . 27 Area 8: Tyrrellstown & Environs Future Mixed Use Development . 28 Area 9: Hansfield SDZ Residential and Mixed Use Development . 29 Area 10: North Blanchardstown . 30 Area 11: Dunsink Lands . 31 SECTION 5: RECOMMENDATIONS & CONCLUSIONS 32 BLANCHARDSTOWN URBAN STRUCTURE PLAN E G DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY AND IMPLEMENTATION A 02 P SPRING 2007 Introduction Section 1 details the key issues and need for an Urban Structure Plan – Development Strategy as the planning vision for the future of Blanchardstown. -

Dublin 15 Community Council

DUBLIN 15 COMMUNITY COUNCIL COMHAIRLE POBAIL, BAILE ATHA CLIATH 15 CLONSILLA HALL, CLONSILLA ROAD, CLONSILLA, DUBLIN 15 TELEPHONE/FAX: 8200559 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.dublin15cc.com A CHUIMSION: BAILE BLAINSEIR-CAISLEAN CNUCHA - CLUAN SAILEACH-MULLACH EADRAD Representing: Blanchardstown-Castleknock-Clonsilla-Mulhuddart Chair: C. Kurtz. Vice Chair: J Greene, Secretary: C Durnin, Treasurer: Leo Gibson, P.R.O: K. O’Neill By e-mailed to [email protected] Senior Executive Officer, Planning Department, Fingal County Council County Hall Swords Co. Dublin 5 December 2007 Dear Sirs, On behalf of DUBLIN 15 COMMUNITY COUNCIL I wish to make the following observations on the Clonsilla Village Urban Centre Strategy, DUBLIN 15. The area is bounded by the Clonsilla Road to the North, the Maynooth rail line to the South, Clonsilla rail station to the West and the Dr Troy Bridge to the East. The intent of the strategy is to create a realistic vision for the future enhancement of the vitality and viability of the Village as an Urban Centre within Dublin 15, providing a framework to guide the formulation of future development proposals. We have structured our submission to address the issues for investigation in the strategy: o Proposals for the co-ordinated development of greenfield sites and future infill development o Creation of a network of safe pedestrian and cyclist routes o Traffic management and car parking strategy for the village o Potential of the Royal Canal as a local amenity and preservation of existing local heritage o Creation of a network of public open spaces and an enhanced public realm and character within the Village Dublin 15 Community Council Page 1 of 8 1.0 Current situation: Clonsilla Village has grown organically over a long period of time, in comparison with the rest of Dublin 15. -

Company Name Site Address Registration No. Activity AV Pound & Co. Limited Goolds Hill House, Old Cork Road, Mallow, Cork

Company Name Site Address Registration No. Activity A.V. Pound & Co. Limited Goolds Hill House, Old Cork Road, Mallow, Cork, P51 FK70, Ireland ASR12130/00001 Distributor AbbVie Ireland NL B.V Manorhamilton Road, Co. Sligo ASR11336/00001 Distributor Allergan Pharmaceuticals International Limited Longphort House, Earlsfort Centre, Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, D02 WK40 ASR12018/00001 Distributor Amdipharm Limited Suite 17,Northwood House, Northwood Avenue, Santry, Dublin 9 ASR11918/00001 Distributor Astellas Ireland Co. Ltd Damastown Road, Damastown Industrial Estate, Mulhuddart, Dublin 15 ASR11341/00001 Distributor Athlone Laboratories Ballymurray, Co. Roscommon ASR11399/00001 Distributor Avara Shannon Pharmaceutical Services Limited Shannon Industrial Estate, Shannon, Co. Clare ASR11990/00001 Distributor BioMarin International Limited Shanbally, Ringaskiddy, Co. Cork, P43 R298 ASR11831/00001 Distributor BNL Sciences Limited Unit S, M7 Business Park, Naas, Kildare ASR11343/00001 Distributor Brenntag Chemicals Distribution (Ireland) Limited Unit 405, Grants Drive, Greenogue Business Park, Rathcoole, Dublin 24 ASR11387/00001 Distributor Bristol-Myers Squibb Swords Laboratories Cruiserath Road, Mulhuddart, Dublin 15 ASR11426/00002 Distributor Camida Ltd Tower House, New Quay, Clonmel, Co. Tipperary ASR11431/00001 Distributor Cara Partners Wallingstown, Little Island Industrial Estate, Co. Cork ASR11494/00001 Distributor Chanelle Medical Dublin Road, Loughrea, Galway ASR11380/00001 Distributor Clarochem Ireland Limited Damastown, Mulhuddart, -

Congratulations Fundraise Towards the Upgrade of Our Carmel Mcnulty (A) Schools IT Infrastructure

WELCOME TO THE CHURCH OF THE GOOD SHEPHERD, CHURCHTOWN Sunday 8th October, 2017. 27th Sunday in Ordinary Time Parish Office Opening Hours: Monday, Thursday, Friday 10.00am – 2 pm Address: Nutgrove Avenue, Churchtown, Dublin 14.. Tel. Numbers: Parish Office: 01 2984642 Sacristy: 2984642 & press 2 Fr. Brian Edwards 01 2984642 Website www.goodshepherdchurchtown.ie E-mail: [email protected] Mass Intentions for the Coming Week World Meeting of Families Celebrating Significant Anniversaries: Six Parishes will mark significant Wedding Saturday 7th October 2017 Anniversaries on Sunday 15th October as part of the preparation for the World Meeting of 10am Katherine & Martin Murphy Junior (A) Families in 2018. Those married in 1947,1957,1967,1977,1987 and 1992 are invited to attend 7.15pm Nora Maher (Months Mind) including those who have been widowed. The events are being organised locally. Tommy Donegan Senior (A) th Mass of Thanksgiving will take place on 15 in John McLoughlin (A) Saint Gabriel’s Church, Dollymount at 10.30 a.m Saint Brigid’s Church, Blanchardstown – 10.30 a.m. Sunday 8th October, 2017 Holy Family Church, Aughrim Street – 11.30 a.m. 10am Seamus Boyne (A) Saint Jude’s Church, Willington – 11.30 a.m. Noel O'Malley (A) Holy Redeemer Church, Bray – 12.00p.m. Deirdre Durkin (Rec) Our Lady of Good Counsel Church, Mourne Road at 12 noon 12pm Andrew Godson (A) Refreshments afterwards - For further information contact relevant parish offices. Nora and Patrick Bracken (A) Official World Meeting of Families Prayer 2018 Sheila Marmion (A) Patrick Young (A) God, our Father, We are brothers and sisters in Jesus your Son, One family, in the Spirit of your Monday love. -

Youth and Sport Development Services

Youth and Sport Development Services Socio-economic profile of area and an analysis of current provision 2018 A socio economic analysis of the six areas serviced by the DDLETB Youth Service and a detailed breakdown of the current provision. Contents Section 3: Socio-demographic Profile OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................... 7 General Health ........................................................................................................................................................... 10 Crime ......................................................................................................................................................................... 24 Deprivation Index ...................................................................................................................................................... 33 Educational attainment/Profile ................................................................................................................................. 38 Key findings from Socio Demographic Profile ........................................................................................................... 42 Socio-demographic Profile DDLETB by Areas an Overview ........................................................................................... 44 Demographic profile of young people ....................................................................................................................... 44 Pobal -

Price Region €400,000

FEATURES: Extensive Wall, Roof & Floor Insulation High Efficiency A Rated Condsensing Gas Boiler Zone Control Heating Thermostatic Radiators Double Glazed Argon Filled Windows New Plumbing & Rewiring Throughout South Facing Rear Garden FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY Gas Fired Central Heating 19 COOLMINE LAWN CLONSILLA DUBLIN 15 D15 T6KR AMENITIES: Only minutes walk to train station, bus stops, shops, family medical centre, playground, crèches, primary and secondary schools, etc. Phoenix Park (incl. Dublin Zoo and Farmleigh), Blanchardstown SC, supermarkets, Castleknock Village and M50 are all less than 10 minutes drive away. The City Centre, Dublin Airport and Heuston Station are also only a short distance. Viewing by appointment only contact ANDREW RAFTER ASSOC. S.C.S.I 086 8199398 [email protected] CORMAC MCCARTHY 086 6488524 [email protected] Flynn & Associates 8211311 PRICE REGION €400,000 Floor Area c. 136 sq.m / 1463 sq.ft Flynn & Associates are delighted to welcome 19 Coolmine Lawn to the open market. This exceptional 3 bedroom semi-detached home with converted garage comes to the market offering turn-key condition with no further work required. Boasting bright and spacious accommodation comprising of welcoming porch and entrance hallway, fabulously configured study / fourth bedroom with mezzanine floor, beautifully refurbished living room, extended open plan kitchen and dining room, three bedrooms (all with fitted wardrobes), and main bathroom. Also benefitting from a sunny South facing rear garden, quiet surroundings, mature green spaces and a location that is always in high demand. Number 19 is ideally located in this mature quiet residential cul de sac, just a short stroll from Roselawn Shopping Centre. -

Irish Marriages, Being an Index to the Marriages in Walker's Hibernian

— .3-rfeb Marriages _ BBING AN' INDEX TO THE MARRIAGES IN Walker's Hibernian Magazine 1771 to 1812 WITH AN APPENDIX From the Notes cf Sir Arthur Vicars, f.s.a., Ulster King of Arms, of the Births, Marriages, and Deaths in the Anthologia Hibernica, 1793 and 1794 HENRY FARRAR VOL. II, K 7, and Appendix. ISSUED TO SUBSCRIBERS BY PHILLIMORE & CO., 36, ESSEX STREET, LONDON, [897. www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com 1729519 3nK* ^ 3 n0# (Tfiarriages 177.1—1812. www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com Seventy-five Copies only of this work printed, of u Inch this No. liS O&CLA^CV www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com 1 INDEX TO THE IRISH MARRIAGES Walker's Hibernian Magazine, 1 771 —-1812. Kane, Lt.-col., Waterford Militia = Morgan, Miss, s. of Col., of Bircligrove, Glamorganshire Dec. 181 636 ,, Clair, Jiggmont, co.Cavan = Scott, Mrs., r. of Capt., d. of Mr, Sampson, of co. Fermanagh Aug. 17S5 448 ,, Mary = McKee, Francis 1S04 192 ,, Lt.-col. Nathan, late of 14th Foot = Nesbit, Miss, s. of Matt., of Derrycarr, co. Leitrim Dec. 1802 764 Kathcrens, Miss=He\vison, Henry 1772 112 Kavanagh, Miss = Archbold, Jas. 17S2 504 „ Miss = Cloney, Mr. 1772 336 ,, Catherine = Lannegan, Jas. 1777 704 ,, Catherine = Kavanagh, Edm. 1782 16S ,, Edmund, BalIincolon = Kavanagh, Cath., both of co. Carlow Alar. 1782 168 ,, Patrick = Nowlan, Miss May 1791 480 ,, Rhd., Mountjoy Sq. = Archbold, Miss, Usher's Quay Jan. 1S05 62 Kavenagh, Miss = Kavena"gh, Arthur 17S6 616 ,, Arthur, Coolnamarra, co. Carlow = Kavenagh, Miss, d. of Felix Nov. 17S6 616 Kaye, John Lyster, of Grange = Grey, Lady Amelia, y. -

CLONRATH Skerries Road, Lusk

CLONRATH Skerries Road, Lusk clonrathhomes.ie Ideal Location Clonrath is a new residential development of high quality 3, 4 and 5 bedroom traditional two storey family homes in a prime location on the Skerries Road in Lusk, Co. Dublin. Surrounded by picturesque country views and mature landscaping, the homes at Clonrath offer an ideal home in a location designed around family life. Clonrath is located 23km north of Dublin City Centre with excellent rail, road and bus connections for an easy commute to the city. With the bustling seaside coastal towns of Skerries and Malahide nearby, Swords village only a few minutes drive away and an easy journey to Dublin City Centre, this location has it all. Love Where You Live 2 3 Picturesque Setting Some of the many fine attractions close to Clonrath include Ardgillan Castle, Newbridge House and Farm at Newbridge Demesne and Malahide Castle & Gardens. The beautiful beaches of Rush, Malahide and Loughshinny are just a short drive away. There is an incredible selection of world class golf courses nearby, including Malahide, Portmarnock, The Island, Skerries and Rush. This is an ideal location with a wonderful lifestyle right on your doorstep and an easy commute to Dublin City Centre , life here in Clonrath gives the perfect balance. Ardgillan Castle Skerries Mills Skerries Mills Ardgillan Castle and Demense Lusk Round Tower 5 4 Skerries Harbour at Dusk Perfectly Connected Lifestyle Living in Clonrath will provide the best of both worlds, a tranquil village lifestyle is right on your doorstep Clonrath is close to a great selection of local primary schools including Lusk National School, Corduff and thanks to the excellent transport links in the area, travelling directly into the heart of Dublin City Centre National School, Hedgestown National School & Rush and Lusk Educate Together N.S. -

FOR SALE OLD NAVAN ROAD, CASTLEKNOCK, DUBLIN 15 by Private Treaty READY to GO RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT SITE

BRADY’S CASTLEKNOCK INN, FOR OLD NAVAN ROAD, CASTLEKNOCK, DUBLIN 15 SALE READY TO GO RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT SITE By Private Treaty Phoenix Park Brady’s Castleknock Inn Train Station Blanchardstown Shopping Centre c.0.783 ACRE DEVELOPMENT SITE. PLANNING FOR 36 2 & 3 BEDROOM APARTMENTS AND PENTHOUSES. DESCRIPTION The subject site is located on the north side of the Old Navan Road and to the south-west of the Navan Road and extends to an area of c.0.317 hectares (c.0.783 acres). The site currently accommodates Brady’s Castleknock Inn which is a two-storey over basement building that accommodates a public house (including a large car park and outdoor smoking area) and restaurant use on the first floor. The property will be sold with vacant possession. It is located within a well-established residential area with Talbot Downs and Talbot Court to the East and West, and a linear park adjacent to the north of the site. The property is located adjacent to the N3 motorway and the M50 orbital motorway which gives direct access to Dublin City Centre and Blanchardstown Shopping Centre. The site has full Planning Permission for 36 apartments in a mix of 2 and 3 bedroom apartments and penthouses with a basement for 69 car spaces and a number of storage units for residents underground. KEY BENEFITS • F.P.P. for 36 apartments a mix of 2 & 3 Bed Apartments. • 50 Bicycle parking spaces. • Regular site in established residential neighbourhood. • c.0.783 acre / 0.317 ha. • Frontages to Old Navan Road and Talbot Downs.