Advisory Circular 90-109A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of Gurney Flap on Supercritical and Natural Laminar Flow Transonic Aerofoil Performance

Effects of Gurney Flap on Supercritical and Natural Laminar Flow Transonic Aerofoil Performance Ho Chun Raybin Yu March 2015 MPhil Thesis Department of Mechanical Engineering The University of Sheffield Project Supervisor: Prof N. Qin Thesis submitted to the University of Sheffield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy Abstract The aerodynamic effect of a novel combination of a Gurney flap and shockbump on RAE2822 supercritical aerofoil and RAE5243 Natural Laminar Flow (NLF) aerofoil is investigated by solving the two-dimensional steady Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equation. The shockbump geometry is predetermined and pre-optimised on a specific designed condition. This study investigated Gurney flap height range from 0.1% to 0.7% aerofoil chord length. The drag benefits of camber modification against a retrofit Gurney flap was also investigated. The results indicate that a Gurney flap has the ability to move shock downstream on both types of aerofoil. A significant lift-to-drag improvement is shown on the RAE2822, however, no improvement is illustrated on the RAE5243 NLF. The results suggest that a Gurney flap may lead to drag reduction in high lift regions, thus, increasing the lift-to-drag ratio before stall. Page 2 Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my beloved grandmother Sandy Yip who passed away during the course of my research, thank you so much for the support, I love you grandma. This difficult journey would not have completed without the deep understanding, support, motivation, encouragement and unconditional love from my beloved parents Maggie and James and my brother Billy. -

SBM20-322 2015 June 23 Temporary

MOONEY INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION SERVICE BULLETIN 165 Al Mooney Road North Kerrville, Texas 78028 SERVICE BULLETIN M20-322 Date: June 23, 2015 THIS BULLETIN IS FAA APPROVED FOR ENGINEERING DESIGN SUBJECT: Temporary Replacement of Icing System Stall Strip MODELS/ SN Mooney Aircraft with Known Icing System Installed AFFECTED: TIME OF AS SOON AS PRACTICABLE COMPLIANCE: INTRODUCTION: For instances involving missing icing system stall strips, airplanes are grounded. To remedy this situation, a temporary non-icing system stall strip can be installed in place of the icing stall strip to allow the aircraft to operate as a “Not Certified for Flight in Known Icing Conditions” aircraft until the icing strip can be installed. This Service Bulletin is to provide instructions for installing the temporary stall strip. The attached compliance card needs to be filled out and returned to Mooney International Corporation upon completion of this Service Bulletin M20-322. WARNING: Flight into known icing conditions and the use of the aircraft’s icing system is prohibited until the permanent icing system stall strip can be installed. This Service Bulletin only allows for a temporary non-icing stall strip to be installed for temporary flight until the permanent icing stall strip can be obtained. INSTRUCTIONS: Read entire procedures before beginning work. INSTALLING TEMPORARY STALL STRIP: 1.1. Disable and secure circuit breaker to prevent accidental operation of icing system. 1.2. Remove all old sealant and thoroughly clean the porous surface of the wing where the temporary stall strip is to be installed. Acceptable cleaning solvents are listed below. NOTE: The primary factor affecting the adhesion of the stall strip is absolute cleanliness of the porous panel. -

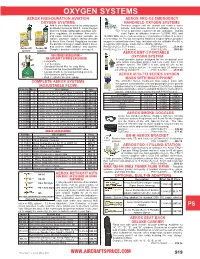

Oxygen Systems

OXYGEN SYSTEMS AEROX HIGH-DURATION AVIATION AEROX PRO-O2 EMERGENCY OXYGEN SYSTEMS HANDHELD OXYGEN SYSTEMS Add to your flying comfort by using oxygen Provides oxygen until the aircraft can reach a lower at altitudes as low as 5000 ft. Aerox Oxygen altitude. And because Pro-O2 is refillable, there is no CM Systems include lightweight aluminum cyl in- need to purchase replacement O2 cartridges. During ders, regulators, all hardware, flow meter, short flights at altitudes between 12,500ft. MSL and and nasal cannulas (masks available as 14,000ft. MSL where maneuvering over mountains or turbulent weather option). Oxysaver oxygen saving cannulas is necessary, the Pro-O2 emergency handheld oxygen system provides & Aerox Flow Control Regulators increase oxygen to extend these brief legs. Included with the refillable Pro-O2 is WP the duration of oxygen supply about 4 times, a regulator with gauge, mask and a refillable cylinder. and prevent nasal irritation and dryness. Pro-O2-2 (2 Cu. Ft./1 mask)........................P/N 13-02735 .........$328.00 Aerox 2D Aerox 4M Complete brochure available on request. Pro-O2-4 (2 Cu. Ft./2 masks) ......................P/N 13-02736 .........$360.00 system system AEROX EMT-3 PORTABLE 500 SERIES REGULATOR – AN AIRCRAFT SPRUCE EXCLUSIVE! OXYGEN SYSTEM ME A small portable system designed for the occasional user • Low profile who wants something smaller and less costly than a full • 1, 2, & 4 place portable system. The EMT-3 is also ideal for use as an • Standard Aircraft filler for easy filling emergency oxygen system. The system lasts 25 minutes at • Convenient top mounted ON/OFF valve 2.5 LPM @ 25,000 FT. -

Cresis UAV Critical Design Review: the Meridian

CReSIS UAV Critical Design Review: The Meridian William Donovan University of Kansas 2335 Irving Hill Road Lawrence, KS 66045-7612 http://cresis.ku.edu Technical Report CReSIS TR 123 June 25, 2007 This work was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (#ANT-0424589). Executive Summary This report briefly describes the development of the three preliminary configuration designs proposed for the Meridian UAV. This report details the selection of the primary configuration and further, more detailed, analysis including Class II weight and Balance, Class II Stability and Control, Performance Analyses, Systems Design, Class II landing gear, structural arrangement, a manufacturing breakdown and a cost analysis. The design mission for this aircraft is to takeoff from a snow or ice runway, fly to a designated area, then use low frequency radar to perform measurements of ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica. Three designs were developed: • A Monoplane with Structurally Integrated Antennas • A Monoplane with Antennas Hanging from the Wing • A Biplane with Antennas Structurally Integrated Into the Lower Wing The monoplane with antennas hanging from the wing was selected as the primary configuration for further development. This report describes the Class II design and analysis of that vehicle. i Acknowledgments This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. AST-0424589. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and -

General Aviation Aircraft Design

Contents 1. The Aircraft Design Process 3.2 Constraint Analysis 57 3.2.1 General Methodology 58 1.1 Introduction 2 3.2.2 Introduction of Stall Speed Limits into 1.1.1 The Content of this Chapter 5 the Constraint Diagram 65 1.1.2 Important Elements of a New Aircraft 3.3 Introduction to Trade Studies 66 Design 5 3.3.1 Step-by-step: Stall Speed e Cruise Speed 1.2 General Process of Aircraft Design 11 Carpet Plot 67 1.2.1 Common Description of the Design Process 11 3.3.2 Design of Experiments 69 1.2.2 Important Regulatory Concepts 13 3.3.3 Cost Functions 72 1.3 Aircraft Design Algorithm 15 Exercises 74 1.3.1 Conceptual Design Algorithm for a GA Variables 75 Aircraft 16 1.3.2 Implementation of the Conceptual 4. Aircraft Conceptual Layout Design Algorithm 16 1.4 Elements of Project Engineering 19 4.1 Introduction 77 1.4.1 Gantt Diagrams 19 4.1.1 The Content of this Chapter 78 1.4.2 Fishbone Diagram for Preliminary 4.1.2 Requirements, Mission, and Applicable Regulations 78 Airplane Design 19 4.1.3 Past and Present Directions in Aircraft Design 79 1.4.3 Managing Compliance with Project 4.1.4 Aircraft Component Recognition 79 Requirements 21 4.2 The Fundamentals of the Configuration Layout 82 1.4.4 Project Plan and Task Management 21 4.2.1 Vertical Wing Location 82 1.4.5 Quality Function Deployment and a House 4.2.2 Wing Configuration 86 of Quality 21 4.2.3 Wing Dihedral 86 1.5 Presenting the Design Project 27 4.2.4 Wing Structural Configuration 87 Variables 32 4.2.5 Cabin Configurations 88 References 32 4.2.6 Propeller Configuration 89 4.2.7 Engine Placement 89 2. -

Pilot´S Operating Handbook

PILOT´S OPERATING HANDBOOK Document Number: AS-POH-10-487 Date of Issue: 07. 05. 2019 Aircraft Model: WT9 Dynamic LSA / Club Aircraft Serial Number: DY-487/2013 LSA Aircraft Registration Number: F-HVXC THIS HANDBOOK INCLUDES THE INFORMATION REQUIRED TO BE FURNISHED TO THE PILOT BY REGULATIONS AND ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PROVIDED BY THE AIRCRAFT MANUFACTURER – AEROSPOOL, SPOL. S R. O. PAGES MARKED AS “EASA APPROVED” ARE APPROVED BY EUROPEAN AVIATION SAFETY AGENCY. THIS AIRCRAFT MUST BE OPERATED IN COMPLIANCE WITH THE INFORMATION AND LIMITATIONS STATED IN THIS MANUAL. This page is left blank intentionally RECORD OF REVISIONS Any revision of the present manual, except actual weight data, must be recorded in the following table, and in the case of approved chapters, endorsed by the responsible airworthiness authority. The new or amended text in the revised pages will be indicated by a black vertical line in the page margin, and the revision will be shown on the bottom side of the page. Revision Date Description of Revision Approved by Initial issue 07. 05. 2019 New issue. Initial issue Page A This page is left blank intentionally Page B Initial issue LIST OF EFFECTIVE PAGES Chapter Page Status Chapter Page Status Title page Initial issue 3 3-1 Initial issue Page Initial issue EASA Approved 3-2 Initial issue Page A Initial issue EASA Approved 3-3 Initial issue Page B Initial issue EASA Approved 3-4 Initial issue Page C Initial issue EASA Approved 3-5 Initial issue Page D Initial issue EASA Approved 3-6 Initial issue Page E Initial issue EASA -

Unusual Attitudes and the Aerodynamics of Maneuvering Flight Author’S Note to Flightlab Students

Unusual Attitudes and the Aerodynamics of Maneuvering Flight Author’s Note to Flightlab Students The collection of documents assembled here, under the general title “Unusual Attitudes and the Aerodynamics of Maneuvering Flight,” covers a lot of ground. That’s because unusual-attitude training is the perfect occasion for aerodynamics training, and in turn depends on aerodynamics training for success. I don’t expect a pilot new to the subject to absorb everything here in one gulp. That’s not necessary; in fact, it would be beyond the call of duty for most—aspiring test pilots aside. But do give the contents a quick initial pass, if only to get the measure of what’s available and how it’s organized. Your flights will be more productive if you know where to go in the texts for additional background. Before we fly together, I suggest that you read the section called “Axes and Derivatives.” This will introduce you to the concept of the velocity vector and to the basic aircraft response modes. If you pick up a head of steam, go on to read “Two-Dimensional Aerodynamics.” This is mostly about how pressure patterns form over the surface of a wing during the generation of lift, and begins to suggest how changes in those patterns, visible to us through our wing tufts, affect control. If you catch any typos, or statements that you think are either unclear or simply preposterous, please let me know. Thanks. Bill Crawford ii Bill Crawford: WWW.FLIGHTLAB.NET Unusual Attitudes and the Aerodynamics of Maneuvering Flight © Flight Emergency & Advanced Maneuvers Training, Inc. -

Assembly Manual

MS:160 ASSEMBLY MANUAL “Graphics and specifications may change without notice”. Specifications: Wing span ------------------------------70.9in (180cm). Wing area -----------------613.8sq.in (39.6sq dm). Weight ------------------------9.7-10.6lbs (4.4-4.8kg). Length ------------------------------58.8in (149.3cm). Engine ------------------ 0.75-0.91cu.in -----2-stroke. 1.00-1.25cu.in -----4-stroke. Radio ------------------- 6 channels with 11 servos. Electric conversion: optional LANCAIR LEGACY Instruction Manual. INTRODUCTION. Thank you for choosing the LANCAIR LEGACY ARTF by SEAGULL MODELS COMPANY LTD. The LANCAIR LEGACY was designed with the intermediate/advanced sport flyer in mind. It is a semi scale airplane which is easy to fly and quick to assemble. The airframe is conventionally built using balsa, plywood to make it stronger than the average ARTF , yet the design allows the aeroplane to be kept light. You will find that most of the work has been done for you already.The motor mount has been fitted and the hinges are pre-installed . Flying the LANCAIR LEGACY is simply a joy. This instruction manual is designed to help you build a great flying aeroplane. Please read this manual thoroughly before starting assembly of your LANCAIR LEGACY . Use the parts listing below to identify all parts. WARNING. Please be aware that this aeroplane is not a toy and if assembled or used incorrectly it is capable of causing injury to people or property. WHEN YOU FLY THIS AEROPLANE YOU ASSUME ALL RISK & RESPONSIBILITY. If you are inexperienced with basic R/C flight we strongly recommend you contact your R/C supplier and join your local R/C Model Flying Club. -

Safe Flight Aoa Manual

Page 3 of 28 Sym A . Dwg. 56201-2 . PROPRIETARY NOTICE This document contains proprietary information and covers equipment in which Safe Flight has proprietary rights. No data contained herein may be duplicated, used, or disclosed, in whole or in part, for any purpose, without the express written permission of Safe Flight Instrument Corporation. Safe Flight Instrument Corporation expressly reserves all rights, including all rights of patent and copyright protection. © SAFE FLIGHT INSTRUMENT CORPORATION 2016 Page 4 of 28 Sym B . Dwg. 56201-2 . TABLE OF CONTENTS Para. Description Page None Title Page ...................................................................................................................... 1 None Revision Notice ............................................................................................................. 2 None Proprietary Notice ......................................................................................................... 3 None Table of Contents .......................................................................................................... 4 1.0 System Description ....................................................................................................... 5 1.1 SCc................................................................................................................................ 5 1.2 System Components ..................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Theory of Operation ..................................................................................................... -

Lancair Legacy RG

Legacy PILOT’S OPERATING HANDBOOK and AIRPLANE FLIGHT MANUAL for the LEGACY Mfgr’s Serial No. ___________________________ Registration No. ___________________________ Owners will need to develop a Pilot’s Operating Handbook as part of the aircraft airworthiness process, and are encouraged to modify this document to help in that process. Legacy Legacy Published by Lancair International Inc. Redmond, Oregon 97756 Authorized Dealer Neico Aviation Inc. 2244 Airport Way Redmond, Oregon 97756 February 2008 iii Legacy Legacy PILOT’S OPERATING HANDBOOK and AIRPLANE FLIGHT MANUAL February 2008 Log of Revisions PAGES DESCRIPTION February 2008 iii Legacy Legacy INTRODUCTION This Lancair International Pilot’s Operating Handbook and Airplane Flight Manual is in the format and contains most data recommended in the GAMA (General Aviation Manufacturers Association) Handbook Specification Number 1. Use of this specification provides the pilot the same type data in the same place in all of the handbooks. For example, attention is called to Section X, SAFETY INFORMATION. We feel it is very important to have this information in a condensed and readily available location and format for the pilots immediate use when needed. This SAFETY INFORMATION should be read and studied by all opera- tors of the Lancair Legacy aircraft and will provide a periodic review of good piloting techniques for this aircraft. This manual will not replace safe flight instruction or good piloting techniques. NOTE Owner modifications to your Lancair may alter the applicability of this handbook which meets the GAMA specification #1 for pilots operating handbooks. WARNING Use only genuine Lancair approved parts obtained from authorized Lancair dealers when repairing and maintaining your Lancair Legacy. -

New Homebuilts No Renum 2013 to 2014 Xlsx

N# Registered Manufacturer Registered Model Name Catalog Name S/N 2214 JUNGSTER 1 1 130 440SS SEGA GARY E 5 5 S 94040013 482FD DAVID R DANTONIO 404 404 X69 66EM MATHERNE EWELL P 582 582 158 2428L SALTERS DANIEL L 7B-15 7B-15 001 498NS SHOWKER JAMES S A26 A26 A2610 495PA DANIEL K SAUL ADE RZ-7 ADE RZ-7 1001 967RJ WATKINS ROBERT M AEROBAT 100 AEROBAT 100 1001 101E NELSON ROGER AERONICA T AERONICA T 1 72417 MERLIN D. PEAY HOBBY-COPTER AH 1 AH 1 2001 503NS SHEKLETON NOEL AIR COMMAND 503 AIR COMMAND 503 S-1 175EC CHARLES D REICHERT AL3 AL3 TX-1033 49AX DENNY ROGER A ALASKA 18 ALASKA 18 0050 312TJ BALENTINE THOMAS J ALLIED T J ALLIED T J 023 504WM MARTIN WILLIAM S ALLIED T J ALLIED T J 022 914AG ABID FAROOQUI APOLLO AG1 APOLLO AG1 USA220713 58835 MCKINSTRY JIM H ARESTI GANADOR ARESTI GANADOR JM-4AG 805PV PEACHEY SAM ARION LIGHTNING ARION LIGHTNING 160 87HC JOHN FRANKLIN AURORA BUTTERFLY AURORA BUTTERFLY B146 342DZ DANIEL ZELAZO AUTOGYRO CALIDUS AUTOGYRO CALIDUS C00342 509PH JOSHUA HUMPHREYS AUTOGYRO CAVALON AUTOGYRO CAVALON V00139 509QB MICHAEL BURTON AUTOGYRO CAVALON AUTOGYRO CAVALON V00138 832TX JASON KNIGHT AUTOGYRO GMBH MTO SP AUTOGYRO GMBH MTO SP M01088 271SF JOHN CHEDESTER AUTOGYRO MTO SPORT AUTOGYRO MTO SPORT M01050 504RD RODNEY L DRISKELL AUTOGYRO MTO SPORT AUTOGYRO MTO SPORT M01072 508FM CRAIG MCPHERSON AUTOGYRO MTO SPORT AUTOGYRO MTO SPORT M01096 502NP ALEXANDER ROLINSKI AVENTURA II AVENTURA II AA2A0166 2378E AVIOTEC SRL AVIASTOL AVIASTOL 001 846WT NOBLE TRAVIS E AVID C AVID C 846 341RP PRANGE RICHARD L AVID C PLUS AVID C PLUS 001 -

Revised Listing of Amateur Built Aircraft Kits

REVISED LISTING OF AMATEUR-BUILT AIRCRAFT KITS Updated on: June 22, 2021 The following is a revised listing of aircraft kits that have been evaluated and found eligible in meeting the “major portion” requirement of Title 14, Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) Part 21, Certification Procedures for Products and Parts, specifically, § 21.191(g). • This listing is only representative of those kits where the kit manufacturer or distributor requested an evaluation by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for eligibility and should not be construed as meaning the kit(s) are FAA “certified,” “certificated,” or “approved.” • There are other aircraft kits that may allow a builder to meet the “major portion” requirement of § 21.191(g), but those manufacturers or distributors have not requested an FAA evaluation. • The placement of an aircraft kit on this list is not a prerequisite for airworthiness certification. • The primary purpose of this listing is to assist FAA Inspectors/Designees and other interested individuals by eliminating the duplication of evaluations for “major portion” determination when the aircraft is presented for airworthiness certification as an “Amateur-Built Experimental.” • Kit manufacturers or distributors whose status is unknown are identified with a question (?) mark and their address has been deleted. Additional Information and Guidance • Advisory Circular (AC) 20-27G, Certification and Operation of Amateur-Built Aircraft. • FAA Order 8130.35B, Amateur-Built Aircraft National Kit Evaluation Team • Contact your local FAA Flight Standards District Office (FSDO) or Manufacturing Inspection District Office (MIDO). Those publications and other information pertaining to amateur-built experimental aircraft are available online at http://www.faa.gov/aircraft.