Here to Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 1 of 156

Page 1 of 156 Page 2 of 156 Page 3 of 156 Page 4 of 156 Page 5 of 156 Page 6 of 156 Page 7 of 156 TABLE OF CONTENTS NBA PRAYER 2 PRESIDENT 3 GENERAL SECRETARY 4 EXECUTIVES 5 NEC NOTICE 7 MINUTES OF DECEMBER NEC MEETING 8 5TH DECEMBER, 2019 PRESIDENT SPEEECH FINANCIAL REPORT 39 2019 (10%) BAR PRACTICE FEE REMITTANCE 64 TO NBA BRANCHES NBA 2019 AGC; PRESIDENT’S EXPLANATORY NOTE 69 NBA AGC 2019 FINANCIAL REPORT 71 NBA COMMITTEE REPORTS I. WOMEN’S FORUM 83 II. TECHNICAL COMMITTEE ON 100 CONFERENCE PLANNING III. SECTION ON PUBLIC INTEREST AND 139 DEVELOPMENT LAW REPORT IV. SECTION ON BUSSINESS LAW REPORT 141 V. SECTIONON ON LEGAL PRACTICE REPORT 147 VI. YOUNG LAWYERS’ FORUM 149 VII. LETTER OF COMMENDATION TO NBA BAR SERVICES DEPARTMENT Page 8 of 156 MINUTES OF THE NATIONAL EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE (NEC) MEETING OF THENIGERIAN BAR ASSOCIATION, HELD ON 5THDECEMBER, 2019 AT THE AUDITORIUM, NBA HOUSE NATIONAL SECRETARIAT ABUJA. 1.0. MEMBERS PRESENT: NATIONAL OFFICERS 1. PAUL USORO, SAN PRESIDENT 2. JONATHAN GUNU TAIDI, ESQ GENERAL SECRETARY 3. STANLEY CHIDOZIE IMO, ESQ 1ST VICE PRESIDENT 4. THEOPHILUS TERHILE IGBA , ESQ 3RD VICE PRESIDENT 5. BANKE OLAGBEGI-OLOBA, ESQ TREASURER 6. NNAMDI INNOCENT EZE, ESQ LEGAL ADVISER 7. JOSHUA ENEMALI USMAN, ESQ WELFARE SECRETARY 8. ELIAS EMEKA ANOSIKE, ESQ FINANCIAL SECRETARY 9. OLUKUNLE EDUN, ESQ PUBLICITY SECRETARY 10. EWENODE WILLIAM ONORIODE, ESQ 1ST ASST. SECRETARY 11. CHINYERE OBASI, ESQ 2ND ASST. SECRETARY 12. IRENE INIOBONG PEPPLE, ESQ ASST. FIN. SECRETARY 13. AKOREDE HABEEB LAWAL, ESQ ASST. PUB. -

Foreign Exchange Auction No. 32/2002

CENTRAL BANK OF NIGERIA, ABUJA FOREIGN OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT FOREIGN EXCHANGE AUCTION NO. 32/2002 FOREIGN EXCHANGE AUCTION RESULT SCHEDULE OF 06TH NOVEMBER, 2002 APPLICANT NAME FORM BID CUMMULATIVE BANK REMARKS S/N A. SUCCESSFUL BIDS M'/ 'A' NO. R/C NO APPLICANT ADDRESS RATE AMOUNT TOTAL PURPOSE NAME 1 DATAMEDICS NIGERIA LIMITED MF0215516 187241 71, ALLEN AVENUE, IKEJA, LAGOS 128.0000 17,019.00 17,019.00 X-RAY FILM LIFE RAY AFRIBANK 0.0317 2 DEMA INVESTMENT (NIG) LTD. AA0685970 18194 13, BAMISHILE STREET, IKEJA, LAGOS 128.0000 1,764.50 18,783.50 LIVING EXPENSES AFRIBANK 0.0033 3 E.C.BROWN & CO LTD M0194337 296621 73,OZOMAGALA ST.,ONISHA 128.0000 16,650.00 35,433.50 WHEEL BARROW TYRE ACCESS 0.0311 4 International Tools Ltd. MF0016297 5820206 10 Abebe Village Road, Iganmu - Surulere 128.0000 14,035.05 49,468.55 Mobile Workshop Cranes, Hydraulic Bootle Jacks, Mechanic HandUBA PLCChain Hoist, Push0.0262 Trolley for hand Chain Hoist, Electro-Chain Hoist 5 J.A.NDUBISI & CO LTD MF0371202 219270 36B,OZOMAGALA ST.,ONISHA 128.0000 15,750.00 65,218.55 WASHING POWDER ACCESS 0.0294 6 JOSEPH O. ORENAIKE AA0745974 A0160632 MOBIL PRODUCING NIG. UNLTD, GIS DEPT. QIT128.0000 4,183.00 69,401.55 TUITION FEE ECOBANK 0.0078 7 LA VIVA NIG LTD MF0203561 RC45837 195B CORPORATION DRIVE DOLPHIN ESTATE 128.0000 LAGOS 18,000.00 87,401.55 TV AND CLOCKS ACB 0.0336 8 OLUGBEJE TITILAYO A0578183 AA0717891 10A KOSOKO STREET,EREKO.LAGOS 128.0000 2,000.00 89,401.55 PTA GATEWAY 0.0037 9 ONOM ENTERPRISES MF0358897 LAZ092413 10 SEBANJO STREET, PAPA, AJAO, MUSHIN 128.0000 21,450.00 110,851.55 RAW MATERIALS:PRINTING PAPER IN SHEETS TRIUMPH 0.0400 10 ROSHAN NIGERIA LIMITED MF0393369 40822 36 MORRISON CRESCENT OREGUN IKEJA LAGOS 128.0000 36,572.50 147,424.05 HOME APPLIANCES STD CHART. -

Public Disclosure Authorized

INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION THE INSPECTION PANEL 1818 H Street, N.W. Telephone: (202) 458-5200 Washington, D.C. 20433 Fax: (202) 522-0916 Email: [email protected] Eimi Watanabe Chairperson Public Disclosure Authorized JPN REQUEST RQ13/09 July 16, 2014 MEMORANDUM TO THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS OF THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Request for Inspection Public Disclosure Authorized NIGERIA: Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (P071340) Notice of Non Registration and Panel's Observations of the First Pilot to Support Early Solutions Please find attached a copy of the Memorandum from the Chairperson of the Inspection Panel entitled "Request for Inspection - Nigeria: Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (P071340) - Notice of Non Registration and Panel's Observations of the First Pilot to Support Early Solutions", dated July 16, 2014 and its attachments. This Memorandum was also distributed to the President of the International Development Association. Public Disclosure Authorized Attachment cc.: The President Public Disclosure Authorized International Development Association INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION THE INSPECTION PANEL 1818 H Street, N.W. Telephone: (202) 458-5200 Washington, D.C. 20433 Fax : (202) 522-0916 Email: [email protected] Eimi Watanabe Chairperson IPN REQUEST RQ13/09 July 16, 2014 MEMORANDUM TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Request for Inspection NIGERIA: Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (P071340) Notice of Non Registration and Panel's Observations of the First Pilot to Support Early Solutions Please find attached a copy of the Memorandum from the Chairperson of the Inspection Panel entitled "Request for Inspection - Nigeria: Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (P07 J340) - Notice of Non Registration and Panel's Observations of the First Pilot to Support Early Solutions" dated July 16, 2014 and its attachments. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses An Auto-Ethnographical Study of Integration of Kanuri Traditional Health Practices into the Borno State Health Care Stystem El-Yakub, Kaka How to cite: El-Yakub, Kaka (2009) An Auto-Ethnographical Study of Integration of Kanuri Traditional Health Practices into the Borno State Health Care Stystem, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/171/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 AN AUTO-ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF INTEGRATION OF KANURI TRADITIONAL HEALTH PRACTICES INTO THE BORNO STATE HEALTH CARE SYSTEM by Hajja Kaka El-Yakub a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Applied Social Sciences Durham University November 2009 Supervisors: Prof. David Byrne and Dr Andrew Russell Contents Declaration i Abstract ii Acknowledgements -

S/No Registration Number Candidate Full Name State

LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR PHYSICAL SCREENING 2018 RECRUITMENT EXERCISE FOR CONSTABLES (ADAMAWA STATE) REGISTRATION LOCAL S/NO NUMBER CANDIDATE FULL NAME STATE GOVERNMENT GENDER 1 ADM/PC/1001000 EVANS LUTONO ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 2 ADM/PC/1001918 IBRAHIM NZADON YAHAYA ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 3 ADM/PC/1004500 JULIUS NUMBAMI ELIHU ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 4 ADM/PC/1006276 KADMIEL PUSHITAYANG ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 5 ADM/PC/1006739 MUHAMMAD JAFAR A ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 6 ADM/PC/1007623 WILSON MISHINARAM ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 7 ADM/PC/1010283 AMOS LINUS ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 8 ADM/PC/1015520 SIMON SUNDAY ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 9 ADM/PC/1022435 ZANYE PANASOM ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 10 ADM/PC/1024856 RAPHAEL RAYON ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 11 ADM/PC/1025782 MUSA PAUL ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 12 ADM/PC/1026355 DENHAM HASSAN ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 13 ADM/PC/1026514 SAMSON GODIYA ADAMAWA DEMSA FEMALE 14 ADM/PC/1029100 GABRIEL TAPWARI ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 15 ADM/PC/1032470 SAMSON GODIYA ADAMAWA DEMSA FEMALE 16 ADM/PC/1034069 JAMES JIMMY ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 17 ADM/PC/1036334 DIMAS MURTE BWALMO ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 18 ADM/PC/1036747 SURAM DAPIKYAM ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 19 ADM/PC/1039861 GABRIEL CHAMATAM TAPWARI ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 20 ADM/PC/1044992 ANTIBAS ISHAKU AMOS ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 21 ADM/PC/1046404 PHINEAS EMMANUEL ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 22 ADM/PC/1048112 JESSY PETER MANJI ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 23 ADM/PC/1052092 JULIUS JIL JAMEEL ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE SUCCESSFUL LIST FOR PHYSICAL SCREENING 2018 CONSTABLES RECRUITMENT EXERCISE 5/4/2018 1/271 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR PHYSICAL SCREENING 2018 RECRUITMENT -

RIGGING THROUGH the COURTS: the Judiciary and Electoral Fraud in Nigeria

VOLUME 13 NO 2 137 RIGGING THROUGH THE COURTS: The Judiciary and Electoral Fraud in Nigeria Hakeem Onapajo and Ufo Okeke Uzodike Hakeem Onapajo is a PhD candidate in the School of Social Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa e-mail: [email protected] Ufo Okeke Uzodike is Professor of International Relations, School of Social Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Since Nigeria’s return to democratic rule in 1999 elections in the country have been accompanied by reports of widespread fraud. A number of studies have illustrated the many ways in which electoral fraud is perpetrated in Nigeria. However, there is yet to be a serious study showing the judicial dimension to such fraud. This study reveals the relationship of the judiciary to electoral fraud. Analysing data sourced from written records (newspaper reports, election observers’ reports, law reports and political party publications) and interviews, the study argues that the structure and condition of the Nigerian judiciary can help to explain the incidence of electoral fraud in the country. It also makes a new contribution to the existing literature on the nature and causes of electoral fraud, showing that non-electoral institutions, especially the judiciary, and non-political elites can be relevant to the explanation of electoral fraud in a country. INTRODUCTION In Nigerian [electoral] politics now, the wisdom is: Don’t waste your time campaigning. Don’t waste your money printing billboards, handbills or posters. Don’t waste your time throwing away money for mobilisation. Just keep your money in the bank and call a very good lawyer and let him tell you the loopholes in the Constitution or the Electoral Act. -

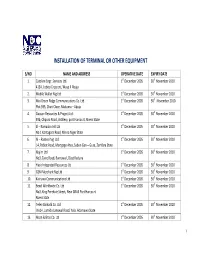

Installation of Terminal Or Other Equipment

INSTALLATION OF TERMINAL OR OTHER EQUIPMENT S/NO NAME AND ADDRESS OPERATIVE DATE EXPIRY DATE 1. Catoline Engr. Services Ltd. 1st December 2005 30 th November 2010 413A, Lobito Crescent, Wuse II Abuja 2. Mobile Wallet Nig Ltd 1st December 2005 30 th November 2010 3. Moi Green Ridge Communications Co. Ltd. 1st December 2005 30 th November 2010 Plot 595, Chari Close, Maitama – Abuja 4. Gauson Resources & Project Ltd. 1st December 2005 30 th November 2010 49b, Okporo Road, Artillery, port Harcourt, Rivers State 5. El – Ramadan Intl Ltd 1st December 2005 30 th November 2010 No.1 Kontagora Road, Minna Niger State 6. Al – Rantesi Nig Ltd 1st December 2005 30 th November 2010 14, Rabiat Road, Mortgage Atea, Sabon Gari – Gusa, Zamfara State 7. Alajim Ltd 1st December 2005 30 th November 2010 No3, Zaire Road, Bar nawa L/Cost Kaduna 8. Haziz Integrated Resources Ltd 1st December 2005 30 th November 2010 9. GSM Merchant Nig Ltd 1st December 2005 30 th November 2010 10. Kainuwa Communications Ltd 1st December 2005 30 th November 2010 11. Bexel Worldwide Co. Ltd 1st December 2005 30 th November 2010 No3, King Perekule Street, New GRAII Port Harcourt Rivers State 12. Tefen Barka & Co. Ltd 1st December 2005 30 th November 2010 No14, Lamido Lanuwal Road, Yola, Adamawa State 13. Alson & Bros Co. Ltd 1st December 2005 30 th November 2010 1 No.25, St Micheals Road, Aba Abia State 14. Mirk Communications Ltd 1st December 2005 30 th November 2010 Shop No4, Ekeson park Utako Abuja, 15. Open Heavens Network Nig Ltd 1st December 2005 30 th November 2010 Wo 113, Jakpa Road, Effurun Delta State 16. -

2017 Annual Report

NATIONAL PENSION COMMISSION (PenCom) 2017 ANNUAL REPORT CORPORATE VISION AND MISSION STATEMENT Corporate Vision “By 2019, to be a pension industry with 20 million contributors delivering measurable impact on the Economy” Mission Statement “PenCom exists for the effective regulation and supervision of the Nigerian Pension Industry to ensure that retirement benefits are paid as and when due” i EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE MEMBERS Mrs. Aisha Dahir-Umar Acting Director General ii MANAGEMENT CONSULTATIVE COMMITTEE MEMBERS Mrs. Aisha Dahir- Umar Acting Director General Mr. Mohammed Bello Umar Head (Compliance & Enforcement Department) Mrs. Grace Usoro Head (National Databank Management Department) Mr. Mohammed Yola Datti Head (Surveillance Department) Mr. Moses O. Loyinmi Head (Contributions & Bond Redemption Department) Mrs. Ekanem B. Aikhomu Head (Benefits & Insurance Department) Dr. Dan Ndackson Head (State Operations Department) Dr. Umar F. Aminu Head (Research & Strategy Management Department) Mr. Ehimeme Ohioma Head (Investment Supervision Department) Mr. Aliyu A. Tijjani Head (Corporate Responsibility & SERVICOM Department) Mr. Tijjani A. Saleh Head (Management Services Department) Mr. Peter Nwabuike Ekwealor Head (Internal Audit Department) Mr. Polycarp Nzeadibe C. Head (Information & Communication Technology Anyanwu Department) Mr. Adamu S. Kollere Head (Director General’s Office Department) Mr. Muhammad S. Muhammad Commission Secretariat/Legal Advisory Services Department Mr. Peter Agahowa Head (Corporate Communications Department) Mr. Bala -

Download List of Shortlisted Candidates for Interview 2020/2021

NIGERIAN MILITARY SCHOOL LIST OF SHORTLISTED CANDIDATES AND REQUIREMENTS FOR 2020 SELECTION BOARD INTERVIEW 1. The Candidates whose names appear in this publication were successful at the Nigerian Military School Entrance Examination held on 22 August 2020 at designated Centers nationwide. The shortlisted candidates are to appear at Nigerian Military School Zaria for the Selection Board Interview scheduled to hold between 20 September - 4 October 2020. All candidates are to report to the School unfailingly on 20 September 2020. Candidates MUST come along with the following items: a. Original copy of Birth Certificate. b. Original copy of Local Government and State of Origin Certificate. c. Primary School Certificate and Testimonial. d. Original copy of examination photo card. e. Passport photograph (4 copies). f. Chest X-ray from a Government or Military Hospital. g. A medical certificate of fitness from a Government or Military Hospital. h. White vest – 2. i. White short knickers – 2. j. White canvas– 1. k. White socks - 2 pairs. l. Bathroom Slipper – 1 pair. m. Cutleries – 1 Set. n. Toiletries. o. Writing Materials. p. Eating utensils. q. Blanket - 1. r. Bucket - 1. s. Broom - 1 t. Mosquito Net – 1. u. Bed Sheet – 1. v. Face Mask - 2 w. Administration fees Eleven Thousand Naira (N11,000.00) only cash. x. For further information please call: 09055522283 or 09055522284. LIST OF SHORTLISTED CANDIDATES FOR NIGERIAN MILITARY SCHOOL 2020/2021 SELECTION BOARD INTERVIEW Serial Candidate Names Exam No Remarks (a) (b) (c) (d) ABIA STATE 1 OGWO -

2015 ANNUAL REPORT & Statement of Accounts

NATIONAL PENSION COMMISSION (PenCom) 2015 ANNUAL REPORT & Statement of Accounts CORPORATE VISION AND MISSION STATEMENT Corporate Vision “By 2019, to be a pension industry with 20 million contributors delivering measurable impact on the Economy” Mission Statement “PenCom exists for the effective regulation and supervision of the Nigerian Pension Industry to ensure that retirement benefits are paid as and when due” i EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE MEMBERS Chinelo Anohu-Amazu Director General Ebenezer Foby Adesoji Olaoba-Efuntayo Commissioner, Administration Commissioner, Finance & Investment Prof. Muhammed A. Kaoje Reuben G. Omotowa Commissioner, Inspectorate Commissioner, Technical ii MANAGEMENT CONSULTATIVE COMMITTEE MEMBERS Mrs. Chinelo Anohu-Amazu Director General Prof. Mohammed K. Abubakar, FSA Commissioner Inspectorate Mr. Rueben G. Omotowa Commissioner Technical Barrister Adesoji Olaoba-Efuntayo Commissioner Finance & Investment Mr. Ebenezer Foby Commissioner Administration Mrs. Aisha I. Mustafa Head (Management Services Department) Mr. Muhammad B. Umar Head (Compliance & Enforcement Department) Mrs. Grace Usoro Head (Public Sector Pensions Department) Mr. Muhammad Y. Datti Head (Surveillance Department) Mr. Moses O. Loyinmi Head (Benefits & Insurance Department) Mrs. Ekanem B. Aikhomu Head (National Databank Department) Mr. Inuwa O. Iyodo Head (Finance Department) Dr. Dan Ndackson Head (Human Capital Department) Dr. Umaru F. Aminu Head (Research & Corporate Strategy Department) Mr. Ehimeme Ohioma Head (Investment Supervision Department) Mr. -

Politics and Law: Anatomy of the Siamese Twins”

UNIVERSITY OF ILORIN THE ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY-THIRD (153rd) INAUGURAL LECTURE “POLITICS AND LAW: ANATOMY OF THE SIAMESE TWINS” By Professor Mojeed Olujinmi A. Alabi BSc (Ife), MSc (Ife), PhD (Ibadan) in Political Science; LLB (Ibadan), LLM (Ife), PhD (Leicester) in Law; BL, FJAPSS Department of Political Science University of Ilorin, Nigeria THURSDAY, 13 NOVEMBER 2014 i This (153rd) Inaugural Lecture was delivered under the Chairmanship of: The Vice-Chancellor Professor Abdul Ganiyu Ambali DVM (Zaria); M.V.Sc., Ph.D. (Liverpool); MCVSN (Abuja) November, 2014 ISBN: 978-978-53221-1-8 Published by The Library and Publications Committee University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria. Printed by Unilorin Press, Ilorin, Nigeria. ii Professor Mojeed Olujinmi A. Alabi BSc (Ife), MSc (Ife), PhD (Ibadan) in Political Science; LLB (Ibadan), LLM (Ife), PhD (Leicester) in Law; BL, FJAPSS Professor of Political Science iii BLANK iv Courtesies Chairman and Vice Chancellor DVCs (Academic, Management Services, and Research, Technology &Innovation) Members of the University Council Registrar and other Principal Officers of the University Provost and Deans, especially Dean of Social Sciences Professors, HODs and other Members of Senate Other academic colleagues Other Members of the Staff of the University Distinguished political leaders and associates Learned Men and Ladies of the Bar and the Bench Gentlemen of the Press Members of my family, nuclear and extended My students, past and present Other invited guests Ladies and gentlemen Introduction By the special grace of Allah, the Lord of the worlds, I stand before this august audience of the intelligentsia and the crème-la-crème of the larger society to present the 153rdInaugural Lecture of this University.This Inaugural Lecture is unique in two respects. -

Yobe State University, Damaturu

YOBE STATE UNIVERSITY, DAMATURU www.ysu.edu.ng The Underlisted candidates have been offered provisional admission into undergraduate programmes for the 2015/2016 academic session. S/No. Reg. Number Name of candidate Course Level 1. 55381497BJ SUNOMA HAUWA MUH'D B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 2. 56404932FF MUSTAPHA MODU KAWU B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 3. 56404367AE SALEH ZAINAB ADAMU B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 4. 55380162EH SAMAILA ABDULWAHAB B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 5. 56489578GD AMINU MAFAZA MAHMUD B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 6. 56404916AJ HARUNA KHADIJA AGO B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 7. 55383016CB BULAMA KADIJA KAKU B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 8. 56766585EB MUH'D AISHA ABDULKADIR B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 9. 56405206AJ RAJI ASMAU RAFIU B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 10. 56115945DA ZAKARIYAU FATIMA GALADIMA B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 11. 55382051AG USMAN ASIYA B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 12. 56405551IC BUKAR MUH'D MALLAMBE B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 13. 56404611EI IBRAHIM ZAHRA GARBA B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 14. 56405215HJ KARFA AISHATU BIZI B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 15. 55380762JA ADAMU ABDULJALAL B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 16. 56407014BH MODUGANA BULAMA BULAMA B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 17. 59050664HI BUKAR HADIZA USMAN B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 18. 59145592IG MALA MUSTI AMINA B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 19. 59015526FD HASSAN JAMILA USMAN B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 20. 59017198IB BUBA HADIZA B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 21. 59155733CE DALA AISHA AJI B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 22. 59077189ED ALI INUSA B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 23. 59015957CB WAKIL MOHAMMED LAWAN B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 24. 59048231BC MUSA HASSAN DAN AZUMI B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 25. 59047558IE M. UMAR MOHAMMED B.Sc. BIOLOGY 100 26. 59080867GH JAMES HANNATU B.Sc.