Capital, Political Vulnerability, and the State in China's Outward Investment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post Event Report

presents 9th Asian Investment Summit Building better portfolios 21-22 May 2014, Ritz-Carlton, Hong Kong Post Event Report 310 delegates representing 190 companies across 18 countries www.AsianInvestmentSummit.com Thank You to our sponsors & partners AIWEEK Marquee Sponsors Co-Sponsors Associate Sponsors Workshop Sponsor Supporting Organisations alternative assets. intelligent data. Tech Handset Provider Education Partner Analytics Partner ® Media Partners Offical Broadcast Partner 1 www.AsianInvestmentSummit.com Delegate Breakdown 310 delegates representing 190 companies across 18 countries Breakdown by Organisation Institutional Investors 46% Haymarket Financial Media delegate attendee data is Asset Managemer 19% independently verified by the BPA Consultant 8% Fund Distributor / Private Wealth Management 5% Media & Publishing 4% Commercial Bank 4% Index / Trading Platform Provider 3% Association 2% Other 9% Breakdown of Institutional Investors Insurance 31% Endowment / Foundation 27% Corporation 13% Pension Fund 13% Family Office 8% Breakdown by Country Sovereign Wealth Fund 6% PE Funds of Funds 1% Mulitlateral Finance Hong Kong 82% Institution 1% ASEAN 10% North Asia 5% Australia 1% Europe 1% North America 1% Breakdown by Job Function Investment 34% Finance / Treasury 20% Marketing and Investor Relations 19% Other 11% CEO / Managing Director 7% Fund Selection / Distribution 7% Strategist / Economist 2% 2 www.AsianInvestmentSummit.com Participating Companies Haymarket Financial Media delegate attendee data is independently verified by the BPA 310 institutonal investors, asset managers, corporates, bankers and advisors attended the Forum. Attending companies included: ACE Life Insurance CFA Institute Board of Governors ACMI China Automation Group Limited Ageas China BOCOM Insurance Co., Ltd. Ageas Hong Kong China Construction Bank Head Office Ageas Insurance Company (Asia) Limited China Life Insurance AIA Chinese YMCA of Hong Kong AIA Group CIC AIA International Limited CIC International (HK) AIA Pension and Trustee Co. -

Allianz Se Allianz Finance Ii B.V. Allianz

2nd Supplement pursuant to Art. 16(1) of Directive 2003/71/EC, as amended (the "Prospectus Directive") and Art. 13 (1) of the Luxembourg Act (the "Luxembourg Act") relating to prospectuses for securities (loi relative aux prospectus pour valeurs mobilières) dated 12 August 2016 (the "Supplement") to the Base Prospectus dated 2 May 2016, as supplemented by the 1st Supplement dated 24 May 2016 (the "Prospectus") with respect to ALLIANZ SE (incorporated as a European Company (Societas Europaea – SE) in Munich, Germany) ALLIANZ FINANCE II B.V. (incorporated with limited liability in Amsterdam, The Netherlands) ALLIANZ FINANCE III B.V. (incorporated with limited liability in Amsterdam, The Netherlands) € 25,000,000,000 Debt Issuance Programme guaranteed by ALLIANZ SE This Supplement has been approved by the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (the "CSSF") of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg in its capacity as competent authority (the "Competent Authority") under the Luxembourg Act for the purposes of the Prospectus Directive. The Issuer may request the CSSF in its capacity as competent authority under the Luxemburg Act to provide competent authorities in host Member States within the European Economic Area with a certificate of approval attesting that the Supplement has been drawn up in accordance with the Luxembourg Act which implements the Prospectus Directive into Luxembourg law ("Notification"). Right to withdraw In accordance with Article 13 paragraph 2 of the Luxembourg Act, investors who have already agreed to purchase or subscribe for the securities before the Supplement is published have the right, exercisable within two working days after the publication of this Supplement, to withdraw their acceptances, provided that the new factor arose before the final closing of the offer to the public and the delivery of the securities. -

China Data Supplement

China Data Supplement October 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 29 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 36 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 45 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR................................................................................................................ 54 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR....................................................................................................................... 61 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 66 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 October 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Issue 1 2013

ISSUE 1 · 2013 NPC《中国人大》对外版 CHAIRMAN ZHANG DEJIANG VOWS TO PROMOTE SOCIALIST DEMOCRACY, RULE OF LAW ISSUE 4 · 2012 1 Chairman of the NPC Standing Committee Zhang Dejiang (7th, L) has a group photo with vice-chairpersons Zhang Baowen, Arken Imirbaki, Zhang Ping, Shen Yueyue, Yan Junqi, Wang Shengjun, Li Jianguo, Chen Changzhi, Wang Chen, Ji Bingxuan, Qiangba Puncog, Wan Exiang, Chen Zhu (from left to right). Ma Zengke China’s new leadership takes 6 shape amid high expectations Contents Special Report Speech In–depth 6 18 24 China’s new leadership takes shape President Xi Jinping vows to bring China capable of sustaining economic amid high expectations benefits to people in realizing growth: Premier ‘Chinese dream’ 8 25 Chinese top legislature has younger 19 China rolls out plan to transform leaders Chairman Zhang Dejiang vows government functions to promote socialist democracy, 12 rule of law 27 China unveils new cabinet amid China’s anti-graft efforts to get function reform People institutional impetus 15 20 28 Report on the work of the Standing Chairman Zhang Dejiang: ‘Power China defense budget to grow 10.7 Committee of the National People’s should not be aloof from public percent in 2013 Congress (excerpt) supervision’ 20 Chairman Zhang Dejiang: ‘Power should not be aloof from public supervision’ Doubling income is easy, narrowing 30 regional gap is anything but 34 New age for China’s women deputies ISSUE 1 · 2013 29 37 Rural reform helps China ensure grain Style changes take center stage at security Beijing’s political season 30 Doubling -

WIC Template 13/9/16 11:52 Am Page IFC1

In a little over 35 years China’s economy has been transformed Week in China from an inefficient backwater to the second largest in the world. If you want to understand how that happened, you need to understand the people who helped reshape the Chinese business landscape. china’s tycoons China’s Tycoons is a book about highly successful Chinese profiles of entrepreneurs. In 150 easy-to- digest profiles, we tell their stories: where they came from, how they started, the big break that earned them their first millions, and why they came to dominate their industries and make billions. These are tales of entrepreneurship, risk-taking and hard work that differ greatly from anything you’ll top business have read before. 150 leaders fourth Edition Week in China “THIS IS STILL THE ASIAN CENTURY AND CHINA IS STILL THE KEY PLAYER.” Peter Wong – Deputy Chairman and Chief Executive, Asia-Pacific, HSBC Does your bank really understand China Growth? With over 150 years of on-the-ground experience, HSBC has the depth of knowledge and expertise to help your business realise the opportunity. Tap into China’s potential at www.hsbc.com/rmb Issued by HSBC Holdings plc. Cyan 611469_6006571 HSBC 280.00 x 170.00 mm Magenta Yellow HSBC RMB Press Ads 280.00 x 170.00 mm Black xpath_unresolved Tom Fryer 16/06/2016 18:41 [email protected] ${Market} ${Revision Number} 0 Title Page.qxp_Layout 1 13/9/16 6:36 pm Page 1 china’s tycoons profiles of 150top business leaders fourth Edition Week in China 0 Welcome Note.FIN.qxp_Layout 1 13/9/16 3:10 pm Page 2 Week in China China’s Tycoons Foreword By Stuart Gulliver, Group Chief Executive, HSBC Holdings alking around the streets of Chengdu on a balmy evening in the mid-1980s, it quickly became apparent that the people of this city had an energy and drive Wthat jarred with the West’s perception of work and life in China. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2017 ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 5, 2017 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate Nov 24 2008 16:24 Oct 04, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\26811 DIEDRE 2017 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate Nov 24 2008 16:24 Oct 04, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 U:\DOCS\26811 DIEDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2017 ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 5, 2017 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 26–811 PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 16:24 Oct 04, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\26811 DIEDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Senate House MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma Cochairman TOM COTTON, Arkansas ROBERT PITTENGER, North Carolina STEVE DAINES, Montana TRENT FRANKS, Arizona TODD YOUNG, Indiana RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota GARY PETERS, Michigan TED LIEU, California ANGUS KING, Maine EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Department of State, To Be Appointed Department of Labor, To Be Appointed Department of Commerce, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed ELYSE B. -

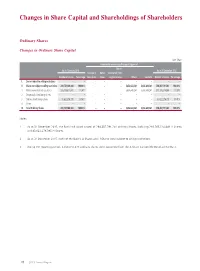

Changes in Share Capital and Shareholdings of Shareholders

Changes in Share Capital and Shareholdings of Shareholders Ordinary Shares Changes in Ordinary Share Capital Unit: Share Increase/decrease during the reporting period Shares As at 1 January 2015 As at 31 December 2015 Issuance of Bonus transferred from Number of shares Percentage new shares shares surplus reserve Others Sub-total Number of shares Percentage I. Shares subject to selling restrictions – – – – – – – – – II. Shares not subject to selling restrictions 288,731,148,000 100.00% – – – 5,656,643,241 5,656,643,241 294,387,791,241 100.00% 1. RMB-denominated ordinary shares 205,108,871,605 71.04% – – – 5,656,643,241 5,656,643,241 210,765,514,846 71.59% 2. Domestically listed foreign shares – – – – – – – – – 3. Overseas listed foreign shares 83,622,276,395 28.96% – – – – – 83,622,276,395 28.41% 4. Others – – – – – – – – – III. Total Ordinary Shares 288,731,148,000 100.00% – – – 5,656,643,241 5,656,643,241 294,387,791,241 100.00% Notes: 1 As at 31 December 2015, the Bank had issued a total of 294,387,791,241 ordinary shares, including 210,765,514,846 A Shares and 83,622,276,395 H Shares. 2 As at 31 December 2015, none of the Bank’s A Shares and H Shares were subject to selling restrictions. 3 During the reporting period, 5,656,643,241 ordinary shares were converted from the A-Share Convertible Bonds of the Bank. 79 2015 Annual Report Changes in Share Capital and Shareholdings of Shareholders Number of Ordinary Shareholders and Shareholdings Number of ordinary shareholders as at 31 December 2015: 963,786 (including 761,073 A-Share Holders and 202,713 H-Share Holders) Number of ordinary shareholders as at the end of the last month before the disclosure of this report: 992,136 (including 789,535 A-Share Holders and 202,601 H-Share Holders) Top ten ordinary shareholders as at 31 December 2015: Unit: Share Number of Changes shares held as Percentage Number of Number of during at the end of of total shares subject shares Type of the reporting the reporting ordinary to selling pledged ordinary No. -

News China March. 13.Cdr

VOL. XXV No. 3 March 2013 Rs. 10.00 The first session of the 12th National People’s Congress (NPC) opens at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, capital of China on March 5, 2013. (Xinhua/Pang Xinglei) Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei meets Indian Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Cheng Guoping , on behalf Foreign Minister Salman Khurshid in New Delhi on of State Councilor Dai Bingguo, attends the dialogue on February 25, 2013. During the meeting the two sides Afghanistan issue held in Moscow,together with Russian exchange views on high-level interactions between the two Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev and Indian countries, economic and trade cooperation and issues of National Security Advisor Shivshankar Menon on February common concern. 20, 2013. Chinese Ambassador to India Mr.Wei Wei and other VIP Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei and Indian guests are having a group picture with actors at the 2013 Minister of Culture Smt. Chandresh Kumari Katoch enjoy Happy Spring Festival organized by the Chinese Embassy “China in the Spring Festival” exhibition at the 2013 Happy and FICCI in New Delhi on February 25,2013. Artists from Spring Festival. The exhibition introduces cultures, Jilin Province, China and Punjab Pradesh, India are warmly customs and traditions of Chinese Spring Festival. welcomed by the audience. Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei(third from left) Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei visits the participates in the “Happy New Year “ party organized by Chinese Visa Application Service Centre based in the Chinese Language Department of Jawaharlal Nehru Southern Delhi on March 6, 2013. -

Turning the Tide on Dirty Money Why the World’S Democracies Need a Global Kleptocracy Initiative

GETTY IMAGES Turning the Tide on Dirty Money Why the World’s Democracies Need a Global Kleptocracy Initiative By Trevor Sutton and Ben Judah February 2021 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Contents 1 Preface 3 Introduction and summary 6 How dirty money went global and why efforts to stop it have failed 10 Why illicit finance and kleptocracy are a threat to global democracy and should be a foreign policy priority 13 The case for optimism: Why democracies have a structural advantage against kleptocracy 18 How to harden democratic defenses against kleptocracy: Key principles and areas for improvement 21 Recommendations 28 Conclusion 29 Corruption and kleptocracy: Key definitions and concepts 31 About the authors and acknowledgments 32 Endnotes Preface Transparency and honest government are the lifeblood of democracy. Trust in democratic institutions depends on the integrity of public servants, who are expected to put the common good before their own interests and faithfully observe the law. When officials violate that duty, democracy is at risk. No country is immune to corruption. As representatives of three important democratic societies—the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom—we recognize that corruption is an affront to our shared values, one that threatens the resiliency and cohesion of democratic governments around the globe and undermines the relationship between the state and its citizens. For that reason, we welcome the central recommendation of this report that the world’s democracies should work together to increase transparency in the global economy and limit the pernicious influence of corruption, kleptocracy, and illicit finance on democratic institutions. -

Chinese Sharp Power Are Political and Economic Elites (“Elite Capture”); Media and Public Opinion; and Civil Society, Grassroots, and Academia

A Macdonald-Laurier Institute Publication THE HARD EDGE OF SHARP POWER Understanding China’s Influence Operations Abroad J. Michael Cole October 2018 Board of Directors CHAIR Richard Fadden Pierre Casgrain Former National Security Advisor to the Prime Minister, Director and Corporate Secretary, Ottawa Casgrain & Company Limited, Montreal Brian Flemming VICE-CHAIR International lawyer, writer, and policy advisor, Halifax Laura Jones Robert Fulford Executive Vice-President of the Canadian Federation Former Editor of Saturday Night magazine, of Independent Business, Vancouver columnist with the National Post, Ottawa MANAGING DIRECTOR Wayne Gudbranson Brian Lee Crowley, Ottawa CEO, Branham Group Inc., Ottawa SECRETARY Calvin Helin Vaughn MacLellan Aboriginal author and entrepreneur, Vancouver DLA Piper (Canada) LLP, Toronto Peter John Nicholson TREASURER Inaugural President, Council of Canadian Academies, Martin MacKinnon Annapolis Royal CFO, Black Bull Resources Inc., Halifax Hon. Jim Peterson DIRECTORS Former federal cabinet minister, Blaine Favel Counsel at Fasken Martineau, Toronto Executive Chairman, One Earth Oil and Gas, Calgary Barry Sookman Jayson Myers Senior Partner, McCarthy Tétrault, Toronto Chief Executive Officer, Jayson Myers Public Affairs Inc., Aberfoyle Jacquelyn Thayer Scott Past President and Professor, Cape Breton University, Dan Nowlan Sydney Vice Chair, Investment Banking, National Bank Financial, Toronto Vijay Sappani Co-Founder and Chief Strategy Officer, Research Advisory Board TerrAscend, Mississauga Veso Sobot