DP World (DPW.DI)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Megaprojects-Based Approach in Urban Planning: from Isolated Objects to Shaping the City the Case of Dubai

Université de Liège Faculty of Applied Sciences Urban Megaprojects-based Approach in Urban Planning: From Isolated Objects to Shaping the City The Case of Dubai PHD Thesis Dissertation Presented by Oula AOUN Submission Date: March 2016 Thesis Director: Jacques TELLER, Professor, Université de Liège Jury: Mario COOLS, Professor, Université de Liège Bernard DECLEVE, Professor, Université Catholique de Louvain Robert SALIBA, Professor, American University of Beirut Eric VERDEIL, Researcher, Université Paris-Est CNRS Kevin WARD, Professor, University of Manchester ii To Henry iii iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My acknowledgments go first to Professor Jacques Teller, for his support and guidance. I was very lucky during these years to have you as a thesis director. Your assistance was very enlightening and is greatly appreciated. Thank you for your daily comments and help, and most of all thank you for your friendship, and your support to my little family. I would like also to thank the members of my thesis committee, Dr Eric Verdeil and Professor Bernard Declève, for guiding me during these last four years. Thank you for taking so much interest in my research work, for your encouragement and valuable comments, and thank you as well for all the travel you undertook for those committee meetings. This research owes a lot to Université de Liège, and the Non-Fria grant that I was very lucky to have. Without this funding, this research work, and my trips to UAE, would not have been possible. My acknowledgments go also to Université de Liège for funding several travels giving me the chance to participate in many international seminars and conferences. -

The Special-Purpose Carrier of Pipe Joints

15JULY1988 MEED 25 Ramazarnanpour Ramazanianpour held talks Denktash. says he is ready for financial aspects of its offer. The group — with the ccfnmerce, heavy and light industry unconditional talks with Greek Cypnot Impreqilo, Cogefar and Gruppo m ministers arid visited the Iranian pavilion at the President George Vassiliou about the Industrie Elettromeccaniche per 24th Algiers international fair. future of the divided island. Impiantl all'Estero (GIE)—plans to start • The Mauntanian towns ot Ak|ou|t and Zouerat In March. Denktash insisted any talks work on the diversionary canal for the dam have received equipment including trucks, must be based on a proposal put forward m September (MEED 24:6:88). trailers, water tanks and tractors from their by UNSecretary-General Javier Perez de Bids for construction of the dam, which Algerian twin towns of Staoueli and Ouenza. Cuellar. The proposal has been reacted will replace the old Esna barrage, were by Greek Cypnots. submitted by 12 international groups in Denktash issued his statement on 6 July December 1986. The field was eventually after a three-day visit to Ankara, where he narrowed to three bidders — the Italian BAHRAIN met Turkey's President Evren and Prime group, Yugoslavia's Energoprojekt, and a Minister TurgutOzal. Canadian consortium of The SWC Group • Bahrain National Gas Company (Banagaa) Vassiliou has refused previous offers to and Canadian International produced 3.2 million barrels a day (b/d) ot Construction Corporation. liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) in 1987. This was meet Denktash on the grounds that the highest daily average since 1979 — its first unacceptable preconditions have been The Italian group brought in Switzerland's year of operations — and 5 percent up on the attached to any meeting. -

Economic Update

Economic Update NBK Economic Research Department I 3 November 2020 Projects > Ensaf Al-Matrouk Research Assistant +965 2259 5366 Kuwait: Project awards pick up in 3Q as [email protected] > Omar Al-Nakib lockdown measures ease Senior Economist +965 2259 5360 [email protected] Highlights The value of project awards increased almost 82% q/q to KD 192 million in 3Q20. Projects awarded were transport and power/water-related; no oil/gas or construction projects were signed. KD 2.1bn worth of awards were penciled in for 2020, however, we expect a smaller figure to materialize. Project awards gather pace in 3Q20, but still fall short of However, with the economy experiencing only a partial recovery expectations so far the projects market is likely to remain subdued; only projects essential to the development plan are likely to be After reaching a multi-year low of KD 106 million in 2Q20, a prioritized. (Chart 3.) quarter that saw business activity heavily impacted by the coronavirus pandemic, the value of project awards increased . Chart 2: Annual project awards nearly 82% q/q in 3Q20 to reach KD 192 million. This is still KD billion, *includes awarded and planned modest by previous standards, however, and is 45% lower than 9 9 the KD 350 million worth of projects approved in in 3Q19. (Chart 8 Transport 8 Power & Water 1). One project award from the Ministry of Public Works’ (MPW), 7 7 accounted for the bulk (86%) of total project awards in the Oil & Gas 6 Construction 6 quarter. 5 Industrial 5 Total projects awarded in 2020 so far stand at KD 866 million 4 4 (cumulative), with about KD 1.3 billion still planned for 4Q20. -

Emiratos Árabes Unidos

INFORME ECONÓMICO Y COMERCIAL Emiratos Árabes Unidos Elaborado por la Oficina Económica y Comercial de España en Dubai Actualizado a octubre 2020 1 1 SITUACIÓN POLÍTICA . 4 1.1 PRINCIPALES FUERZAS POLÍTICAS Y SU PRESENCIA EN LAS INSTITUCIONES . 4 1.2 GABINETE ECONÓMICO Y DISTRIBUCIÓN DE COMPETENCIAS . 4 2 MARCO ECONÓMICO . 4 2.1 PRINCIPALES SECTORES DE LA ECONOMÍA . 4 2.1.1 SECTOR PRIMARIO . 4 2.1.2 SECTOR SECUNDARIO . 7 2.1.3 SECTOR TERCIARIO . 15 2.2 INFRAESTRUCTURAS ECONÓMICAS: TRANSPORTE, COMUNICACIONES Y ENERGÍA . 28 3 SITUACIÓN ECONÓMICA . 34 3.1 EVOLUCIÓN DE LAS PRINCIPALES VARIABLES . 34 CUADRO 1: PRINCIPALES INDICADORES MACROECONÓMICOS . 35 3.1.1 ESTRUCTURA DEL PIB . 36 CUADRO 2: PIB POR SECTORES DE ACTIVIDAD Y POR COMPONENTES DEL GASTO . 37 3.1.2 PRECIOS . 38 3.1.3 POBLACIÓN ACTIVA Y MERCADO DE TRABAJO. DESEMPLEO . 38 3.1.4 DISTRIBUCIÓN DE LA RENTA . 38 3.1.5 POLÍTICAS FISCAL Y MONETARIA . 39 3.2 PREVISIONES MACROECONÓMICAS . 39 3.3 OTROS POSIBLES DATOS DE INTERÉS ECONÓMICO . 39 3.4 COMERCIO EXTERIOR DE BIENES Y SERVICIOS . 40 3.4.1 APERTURA COMERCIAL . 40 3.4.2 PRINCIPALES SOCIOS COMERCIALES . 40 CUADRO 3: EXPORTACIONES POR PAÍSES (PRINCIPALES PAÍSES CLIENTES) . 41 CUADRO 4: IMPORTACIONES POR PAÍSES (PRINCIPALES PAÍSES PROVEEDORES) . 41 3.4.3 PRINCIPALES SECTORES DE BIENES (EXPORTACIÓN E IMPORTACIÓN) . 42 CUADRO 5: EXPORTACIONES POR CAPÍTULOS ARANCELARIOS . 42 CUADRO 6: IMPORTACIONES POR CAPÍTULOS ARANCELARIOS . 42 3.4.4 PRINCIPALES SECTORES DE SERVICIOS (EXPORTACIÓN E IMPORTACIÓN) . 43 3.5 TURISMO . 43 3.5.1. Tipología de los viajes . 43 3.6 INVERSIÓN EXTRANJERA . -

United Arab Emirates

UNITED ARAB EMIRATES GENERAL INFORMATION: Member Trade Bloc: OPEC, GCC, OIC Location: Middle East, bordering the Gulf of Oman and the Persian Gulf, between Oman and Saudi Arabia Capital: Abu Dhabi Area: 83,600 sq km Official language: Arabic Population: 9.3 million (2015) Port & Harbors: Al Hamriya Port, Dubai Chinatown, Dubai Creek, Dubai Flower Centre, Dubai Gold and Diamond Park, Dubai Textile Village, Hamriyah Port, Jebel Ali, Khalifa Port, Khor Fakkan, Musaffah Port, Port of Jebel Ali, Port Rashid, Port Saeed, Western Region Ports, Zayed Port KEY ECONOMIC INDICATORS 2013 2014 2015 2016 GDP (US$ billion) 387.2 399.5 339.1 375.0 GDP per capita (US$) 42,874.6 42,943.8 35,392.2 38,050.2 Real GDP growth (% Change YoY) 4.3 4.6 3.0 2.3 Exports of Goods & Services (% of GDP) 90 98 97.3 97.3 Inflation(% change YOY) 1.1 2.3 3.7 3.6 Unemployment rate (%) 4.1 4.0 3.7 3.5 Total Exports (US$ billion) 379.4 380.3 159.1 - Total Imports (US$ billion) 294.9 298.6 227.2 - GDP – COMPOSITION: Agriculture: 0.7%, Industry: 55.1%, Services: 44.2% MAJOR INDUSTRIES: petroleum and petrochemicals; fishing, aluminum, cement, fertilizers, commercial ship repair, construction materials, handicrafts, textiles MAJOR TRADING PARTNERS OF UAE (2015) Direction of UAE’s Principal Exports to: Direction of UAE’s Principal Imports from: 1. Japan 14.8% 1. China 15.7% 2. Iran 11.4% 2. India 13.4% 3. India 9.6% 3. U.S. 8.9% 4. -

42 MEED Listfinal.Indd

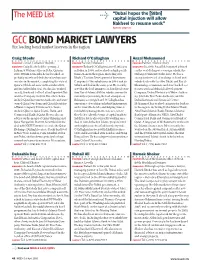

“Dubai hopes the [$8bn] The MEED List Q capital injection will allow Nakheel to resume work” Agenda page 20 GCC BOND MARKET LAWYERS Six leading bond market lawyers in the region Craig Stoehr Richard O’Callaghan Anzal Mohammed POSITION Counsel, Latham & Watkins POSITION Partner, Linklaters POSITION Partner, Allen & Overy BIOGRAPHY Craig Stoehr led the opening of BIOGRAPHY Richard O’Callaghn joined Linklaters BIOGRAPHY In 2009, Anzal Mohammed advised Latham & Watkins office in Doha, Qatar in in Dubai in 2008, and worked on high-profile on the world’s largest sovereign sukuk, the 2008. Within 12 months he had worked on transactions in the region, including Abu Dubai government’s $2bn issue. He has a probably more bond deals by value than any- Dhabi’s Tourism Development & Investment strong track-record of working on bond and one else in the market, completing the state of Company’s $1bn sukuk issue in 2009, and its sukuk deals with the Abu Dhabi and Ras al- Qatar’s $7bn bond issue in November 2009, $1bn bond deal in the same year. He recently Khaimah governments, and state-backed cor- and its earlier $3bn deal. Stoehr also worked acted for the lead arrangers on Saudi real estate porates such as Mubadala Development on a $2.3bn bond for Ras Laffan Liquefied Nat- firm Dar al-Arkan’s $450m sukuk issue and is Company, Dubai Electricity & Water Author- ural Gas Company in 2009. His other clients currently representing the lead arrangers on ity, Jebel Ali Free Zone Authority, and the include Qatar Investment Authority, and state- Bahrain’s sovereign bond. -

Thought Leadership Report GCC LOGISTICS 2017

Thought Leadership Report GCC LOGISTICS 2017 Sponsored By: FOREWORD Mark Geilenkirchen, Chief Executive Officer SOHAR Port and Freezone The office we sit in, the clothes we wear and the food we eat all rely on business planning frameworks that manage material, service, information and capital flows around the globe. This is logistics and by necessity, in today’s increasingly complex business environment, it centres on the communication and control systems required to keep our world moving twenty-four hours a day, each and every day of the year. As one of the world’s fastest growing Port and Freezone developments, logistics is at the core of our business in SOHAR and connects us with markets all over the world. As this is our Year of Logistics, we asked MEED Insight to prepare this special report on the Middle East logistics industry as part of a series of SOHAR sponsored thought leadership reports. We define thought leaders as people or organisations whose efforts are aligned to improve the world by sharing their expertise, knowledge, and lessons learned with others. We believe this knowhow can be the spark behind innovative change, and that’s what we’ve set out to inspire by commissioning this series of reports. 2 GCC LOGISTICS 2016 The GCC Economy GCC Macroeconomic Overview GDP GROWTH GCC VISION PLANS The petrodollar fuelled GCC economies been fairly successful in lowering its oil All the GCC states have formalised strategic, have had a strong run during the first dependency to 42% of GDP in 2014, long- term plans aimed at transforming decade of this millennium, registering a down from 55% in 2008. -

The Dubai Logistics Cluster

THE DUBAI LOGISTICS CLUSTER Alanood Bin Kalli, Camila Fernandez Nova, Hanieh Mohammadi, Yasmin Sanie-Hay, Yaarub Al Yaarubi MICROECONOMICS OF COMPETITENESS COUNTRY OVERVIEW The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a federation of seven emirates, each governed by its own monarch. The seven Emirates - Abu Dhabi, Ajman, Dubai, Fujairah, Ras al-Khaimah, Sharjah, and Umm al-Quwain - jointly form the Federal Supreme Council, which chooses a president every five years. Since independence from Britain in 1971, the ruler of Abu Dhabi has been elected as the president, while the ruler of Dubai has been elected as the Vice President and Prime Minister. Abu Dhabi serves as the capital and each emirate enjoys a high degree of autonomy. The country is strategically located in the Middle East, bordering the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Sea, Oman and Saudi Arabia. It occupies a total area of 83,600 km2 with around 1,318 km of coastline1. The population is estimated to be 9.3 million in 2015 with only 13% nationals2. UAE Economic Performance The UAE is an oil rich country, with most of its oil and gas production coming from Abu Dhabi. The country was ranked eighth worldwide in terms of oil and gas production in 2012 and seventh in terms of reserves3. Since the UAE’s establishment, oil revenues have been used strategically to develop basic infrastructure and provide UAE citizens with government services including subsidized utilities, free education, and medical services. As a result of oil price fluctuation, the country has understood the importance of diversifying away from this resource and started to develop its petrochemical sector. -

The Ten Most Important Ports in the World.Pdf

ΑΚΑΔΗΜΙΑ ΕΜΠΟΡΙΚΟΥ ΝΑΥΤΙΚΟΥ Α.Ε.Ν ΜΑΚΕΔΟΝΙΑΣ ΕΠΙΒΛΕΠΩΝ ΚΑΘΗΓΗΤΗΣ : ΞΕΝΙΤΙΔΟΥ ΕΛΛΗ ΘΕΜΑ “ΤΗΕ TEN MOST IMPORTANT PORTS IN THE WORLD” ΤΟΥ ΣΠΟΥΔΑΣΤΗ : ΤΡΙΑΝΤΑΦΥΛΛΙΔΗ ΓΡΗΓΟΡΙΟΥ Α.Γ.Μ: 2659 Ημερομηνία ανάληψης της εργασίας: Ημερομηνία παράδοσης της εργασίας: Α/Α Ονοματεπώνυμο Ειδικότης Αξιολόγηση Υπογραφή 1 2 3 ΤΕΛΙΚΗ ΑΞΙΟΛΟΓΗΣΗ Ο ΔΙΕΥΘΥΝΤΗΣ ΣΧΟΛΗΣ : [1] CONTENTS Chapter 1 _ Introduction……………………………………………………04 Chapter 2 _ Port of Felixstowe, United Kingdom………………………….05 2.1 _ Description…………………………………………………….. 05 2.1.1 _ Terminals……………………………………………………05 2.1.2 _ Transport Connections……………………………………...06 2.2 _ Current Developments………………………………………….06 2.2.1 _ Felixstowe South……………………………………………06 2.2.2 _ Felixstowe and Nuneaton freight capacity scheme ………...06 2.2.3 _ Copdock Roundabout and general table……………………06 Chapter 3 _ Port of Hamburg, Germany……………………………………08 3.1 _ History…………………………………………………………..08 3.2 _ Access…………………………………………………………...09 3.3 _ Terminals………………………………………………………..09 3.4 _ Cruise……………………………………………………………10 3.5 _ Culture and general table………………………………………..10 Chapter 4 _ Port Hedland, Western Australia………………………………12 4.1 _ History…………………………………………………………..12 4.2 _ About the Harbour………………………………………………13 4.2.1 _ Port Authority……………………………………………….13 4.2.2 _ Geography…………………………………………………..13 4.3 _ Port Statistics…………………………………………………….13 4.4 _ General table…………………………………………………….15 Chapter 5 _ Port of Jebel Ali, United Arab Emirates……………………….16 5.1 _Geography……………………………………………………….16 5.2 _ History…………………………………………………………..17 5.3 _ Operations………………………………………………………17 -

MEED Industry Special Reports 2021

2021-22 Navigate the Middle East The worlds leading source of Middle East business intelligence Launched on International Women’s Day 1957, MEED is a well-known and trusted brand that is used by governments and businesses operating in the region. MEED is a business intelligence service covering the Middle East and North Africa. MEED.com provides daily exclusive news, data and analysis that keeps its subscribers informed about what is going on in the region. Your essential partner for business in the Middle East Supports your planning MEED keeps you up to and decision making date with the region MEED explains changing client needs and policies MEED helps you understand the Middle East Helps you identify new Allows you to track business opportunities your competitors Helps you to identify Supports research challenges and mitigate risks and analysis Unrivalled premium service for business in the Middle East Unique 25-year Archive of Over Middle East Business Newsletters 7,000 direct to your articles published every year inbox MENA MENA MENA economic companies deals indicators database database 60exclusive news and analysis articles a week Access to MEED’s exclusive MENA MENA Middle East city profiles economics market databases 80tender announcements every week MEED Business Review MEED Business Review is the magazine of MEED. It provides MEED subscribers with a monthly report on the Middle East that keeps them informed about what is going on in the region. Delivered in a convenient and beautifully designed format, MEED Business Review is a premium resource curated to help everybody who needs to understand the Middle East. -

Gender and Migration in Arab States

International Labour Organisation GENDER AND MIGRATION IN ARAB STATES: THE CASE OF DOMESTIC WORKERS Edited by Simel Esim & Monica Smith June 2004 Regional Office for Arab States, Beirut International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in this study rests solely on the authors and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of opinions expressed in them. For more information, please contact: Simel Esim Gender & Women Workers’ Specialist Tel: 961 - 1 - 752400 Fax: 961 - 1 - 752405 Email: [email protected] 4 Gender & Migration in Arab States : The Case of Domestic Workers Foreword Domestic workers, the majority of whom are women, constitute a large portion of today's migrant worker population. As part of the international trend of feminization of international labour, much of this work remains invisible in national statistics and national labour legislation. It is not certain whether the increasing participation of women in international migration provides them with a decent wage, good working conditions, social security coverage and labour protection. It is therefore important to provide more attention to the labour situation of the growing number of women migrant workers. To identify critical issues of concern to women migrant domestic workers and to determine the extent of their vulnerability, the ILO has been analyzing the situation in several regions. These studies reveal practices and patterns that are the key causes of the vulnerability of women domestic migrant workers and suggest effective alternative strategies. This publication presents an ILO regional review and four country studies from the Arab States: Bahrain, Kuwait, Lebanon and United Arab Emirates. -

Globalisation and Urban Development: a Case Study of Dubai’S Jumeirah Palm Island Mega Project

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF ENGINEERING SCIENCE & MATHEMATICS SCHOOL OF GEOGRAPHY Globalisation and Urban Development: A Case Study of Dubai’s Jumeirah Palm Island Mega Project By Ibrahim Abdul Rahman Al Darmaki Supervisor: Professor Steven Pinch Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September, 2008 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACUALTY OF ENGINEERING SCIENCE & MATHAMATICS SCHOOL OF GEOGRAPHY Doctor of Philosophy GLOBALISATION AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT: A CASE STUDY OF DUBAI’S JUMEIRAH PALM ISLAND MEGA PROJECT BY IBRAHIM ALDARMAKI ABSTRACT Mega projects have become an important new development strategy in globalizing cities, and a new or emerging form of development in economic, technological, social and political life, influenced by global flows of capital. Despite being acknowledged as an important factor in globalizing economies, the role of mega projects has failed to receive appropriate research attention in terms of analysis of the various advantages and disadvantages that they carry.