Please Read Before Printing!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jay Brown Rihanna, Lil Mo, Tweet, Ne-Yo, LL Cool J ISLAND/DEF JAM, 825 8Th Ave 28Th Floor, NY 10019 New York, USA Phone +1 212 333 8000 / Fax +1 212 333 7255

Jay Brown Rihanna, Lil Mo, Tweet, Ne-Yo, LL Cool J ISLAND/DEF JAM, 825 8th Ave 28th Floor, NY 10019 New York, USA Phone +1 212 333 8000 / Fax +1 212 333 7255 14. Jerome Foster a.k.a. Knobody Akon STREET RECORDS CORPORATION, 1755 Broadway 6th , NY 10019 New York, USA Phone +1 212 331 2628 / Fax +1 212 331 2620 16. Rob Walker Clipse, N.E.R.D, Kelis, Robin Thicke STAR TRAK ENTERTAINMENT, 1755 Broadway , NY 10019 New York, USA Phone +1 212 841 8040 / Fax +1 212 841 8099 Ken Bailey A&R Urban Breakthrough credits: Chingy DISTURBING THA PEACE 1867 7th Avenue Suite 4C NY 10026 New York USA tel +1 404 351 7387 fax +1 212 665 5197 William Engram A&R Urban Breakthrough credits: Bobby Valentino Chingy DISTURBING THA PEACE 1867 7th Avenue Suite 4C NY 10026 New York USA tel +1 404 351 7387 fax +1 212 665 5197 Ron Fair President, A&R Pop / Rock / Urban Accepts only solicited material Breakthrough credits: The Calling Christina Aguilera Keyshia Cole Lit Pussycat Dolls Vanessa Carlton Other credits: Mya Vanessa Carlton Current artists: Black Eyed Peas Keyshia Cole Pussycat Dolls Sheryl Crow A&M RECORDS 2220 Colorado Avenue Suite 1230 CA 90404 Santa Monica USA tel +1 310 865 1000 fax +1 310 865 6270 Marcus Heisser A&R Urban Accepts unsolicited material Breakthrough credits: G-Unit Lloyd Banks Tony Yayo Young Buck Current artists: 50 Cent G-Unit Lloyd Banks Mobb Depp Tony Yayo Young Buck INTERSCOPE RECORDS 2220 Colorado Avenue CA 90404 Santa Monica USA tel +1 310 865 1000 fax +1 310 865 7908 www.interscope.com Record Company A&R Teresa La Barbera-Whites -

The Cord Weekly (November 7, 2001)

Life in Afghanistan: The American What's it really like? economy is like this Page 12_^ pyramid Page 22 CORD Wednesday November 7, 2001 THELaurier'sWEEKLY Official Student • • Issue Newspaper Volume 42 13 3News Growing pains at WLU Students demand answers from university administration Alicia McFadden Business department also Dillon Moore remarked on his personal experi- ence having more students in his Yesterday in the Paul Martin class than he was prepared to han- Centre, a large group gathered to dle. He attempted to draw a com- take part in a town-hall style forum parison between the situation at held by the Students' Union to Laurier to the one at his Alma address the problem of rapid Mater Mount Allison University, growth at Wilfrid Laurier where he felt the enrollment had University. been effectively capped. "I don't Executive Vice President: think we'll lose our identity as a University Affairs Dave Wellhauser small, unique and personal univer- chaired the forum. He welcomed sity," he said. the audience to the event, which Chair of the Board of he stated was one among a series Governors Jerry Young presented planned. Each of the six panelists the side of the administration, pro- was then allowed to make their ducing a number of documents introductory statements. examining growth at Laurier. The panel listens as Rowland Smith describes his thoughts on the sense of community at Laurier Dr. Barry Kay related his expe- "I'm trying to drive home that rience as part of the Political we aren't functioning without a uation at Laurier to that of univer- seen Laurier students receive since "clients" and should be given a Science department. -

8 Crazy in Love BEYONCE FT

KW 37/38/2003 Plz LW WoC Title Artist Distribution PP 1 s 3 8 Crazy In Love BEYONCE FT. JAY - Z Columbia/SONY MUSIC 1 2 s 6 6 Never Leave You (Uh - Oooh) LUMIDEE Universal/UNIVERSAL 2 3 s 10 4 Like Glue SEAN PAUL Atlantic/WARNER 3 4 s NEW 0 Love @ 1st Sight MARY J BLIGE FT. METHOD MAN MCA/UNIVERSAL 4 5 s 12 6 Pump It Up JOE BUDDEN Def Jam/UNIVERSAL 5 6 t 1 4 No Letting Go WAYNE WONDER Atlantic/WARNER 1 7 s 8 8 P.i.m.p. 50 CENT Shady /Aftermath/UNIVERSAL 4 8 t 5 6 Frontin’ PHARRELL WILLIAMS FT. JAY-Z Star Trak/BMG ARIOLA 5 9 s 21 8 Can’t Let You Go (Remix) FABOLOUS Elektra/WARNER 9 10 s 13 10 Breathe BLU CANTRELL FT. SEAN PAUL Arista/BMG ARIOLA 6 11 s NEW 0 La La La (Exuse Me Again) JAY - Z Bad Boy/UNIVERSAL 11 12 s NEW 0 Baby Boy BEYONCE FT. SEAN PAUL Columbia/SONY MUSIC 12 13 t 7 4 Business EMINEM Aftermath/Interscope/UNIVERSAL 7 14 s 19 2 Light Your Ass On Fire BUSTA RHYMES FT. PHARRELL J Records/BMG ARIOLA 14 15 s 39 4 Act A Fool LUDACRIS Def Jam South/UNIVERSAL 15 16 s 22 4 Fäule BEGINNER Buback/Motor/UNIVERSAL 2 17 s NEW 0 Thoia Thoing R. KELLY Jive/BMG ARIOLA 17 18 t 4 6 Where Is The Love BLACK EYED PEAS Interscope/UNIVERSAL 4 19 s NEW 0 Shoomp DE LA SOUL FT. -

The Symbolic Rape of Representation: a Rhetorical Analysis of Black Musical Expression on Billboard's Hot 100 Charts

THE SYMBOLIC RAPE OF REPRESENTATION: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF BLACK MUSICAL EXPRESSION ON BILLBOARD'S HOT 100 CHARTS Richard Sheldon Koonce A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2006 Committee: John Makay, Advisor William Coggin Graduate Faculty Representative Lynda Dee Dixon Radhika Gajjala ii ABSTRACT John J. Makay, Advisor The purpose of this study is to use rhetorical criticism as a means of examining how Blacks are depicted in the lyrics of popular songs, particularly hip-hop music. This study provides a rhetorical analysis of 40 popular songs on Billboard’s Hot 100 Singles Charts from 1999 to 2006. The songs were selected from the Billboard charts, which were accessible to me as a paid subscriber of Napster. The rhetorical analysis of these songs will be bolstered through the use of Black feminist/critical theories. This study will extend previous research regarding the rhetoric of song. It also will identify some of the shared themes in music produced by Blacks, particularly the genre commonly referred to as hip-hop music. This analysis builds upon the idea that the majority of hip-hop music produced and performed by Black recording artists reinforces racial stereotypes, and thus, hegemony. The study supports the concept of which bell hooks (1981) frequently refers to as white supremacist capitalist patriarchy and what Hill-Collins (2000) refers to as the hegemonic domain. The analysis also provides a framework for analyzing the themes of popular songs across genres. The genres ultimately are viewed through the gaze of race and gender because Black male recording artists perform the majority of hip-hop songs. -

Brown Sugar Repertoire – Updated May 2021

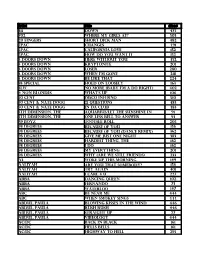

REPERTOIRE No Song Title Artist Name Ballad or Dancing Select 1 Dance Wit Me 112 Dancing 2 Only You (Remix) 112 Dancing 3 Boogie Oogie A Taste Of Honey Dancing 4 Make Me Whole Amel Lerrieux Ballad 5 What’s Come Over Me Amel Lerriex & Glenn Lewis Ballad 6 Let’s Stay Together Al Green Ballad or Dancing 7 Fallin' Alicia Keys Ballad 8 If I Ain’t Got You Alicia Keys Ballad 9 No One Alicia Keys Ballad 10 You Don’t Know My Name Alicia Keys Ballad 11 How Come You Don’t Call Me Alicia Keys Ballad 12 I Swear All 4 One Ballad 13 Consider Me Allen Stone Ballad 14 Taste Of You Allen Stone Dancing 15 Make It Better Anderson .Paak Ballad 16 Leave The Door Open Anderson .Paak | Bruno Mars Ballad 17 Valerie Amy Winehouse Dancing 18 Best Of Me Anthony Hamilton Ballad 19 You Make Me Feel Like A Natural Woman Aretha Franklin Ballad 20 Respect Aretha Franklin Dancing 21 I Say A Little Prayer Aretha Franklin Ballad 22 Until You Come Back to Me Aretha Franklin Ballad 23 Rock Steady Aretha Franklin Dancing 24 Side To Side Ariana Grande Dancing 25 People Everyday Arrested Development Dancing 26 Foolish Ashanti Ballad 27 Nothing On You B.O.B & Bruno Mars Dancing 28 Change The World Babyface Ballad 29 Whip Appeal Babyface Ballad 30 Every time I Close My Eyes Babyface Ballad 31 Can’t Get Enough Of Your Love Baby Barry White Dancing 32 How Deep Is Your Love Bee Gees Ballad 33 Poison Bel Biv Devoe Dancing 34 Love on Top Beyoncé Dancing 35 Déjà vu Beyoncé Dancing 36 Work It Out Beyoncé Dancing 37 Crazy In Love Beyoncé Dancing 38 Halo Beyoncé Ballad 39 Irreplaceable -

We Talk 4C). Radio

OCTOBER 20, 2001 Music Volume 19, Issue 43 £3.95 Tracy Chapman's Collection (Elektra) moves to the num- ber one slot and is this week's Sales Breaker on the Euro- pean Top 100 Albums chart Mediawe talk4c). radio M&M chart toppers this week Merino moves to musicUniversal on Eurochart Hot 100 Singles course to meet KYLIE MINOGUE in Grupo Prisa shake-up Can't Get You Out Of My Head Larsen target (Parlophone) by Howell Llewellyn Groupo Prisa, Jaime Polanco, until European Top 100 Albums now GVM's CEO, takes the up the by Emmanuel Legrand TRACY CHAPMAN MADRID - Luis Merino, who cur-new post of director of Grupo Prisa's Collection rently heads up SER's four nationalInternational Communications LONDON - Universal Music (Elektra) music radionetworks, has beenMedia division. Polanco was also increased its dominance of Europe's appointed to a powerful new execu-previously director general of Prisa's charts during the third quarter of European Radio Top 50 tive post at SER's parent North America operations 2001, and is getting ever closer to MICHAEL JACKSON companyGrupoPrisa, based in New York. No the 30% market share target set by You Rock My World which will see him in con- replacement has yet been Universal Music International (Epic) trol of themedia con- named for Polanco. chairman Jorgen Larsenafew glomerate's record com- Meanwhile, SER's weeks ago (M&M, September 29). European Dance Traxx pany interests. director-general Augusto In both M&M's pan-European ROGER SANCHEZ Merino, 47, has been Delkader moves to the singles and album sales charts, the Another Chance made director of Prisa's post of director of Grupo French -owned major label has made (R-Senal/Sony) Leisure and Entertain- Prisa's newly -created significant progress, achieving close ment division, in effect MediaCommunications to 30% in album chart share and Inside M&M this week makinghim CEOof Spain division. -

Dangerfields

DANGERFIELDS Full Time Professional Disc Jockey Hire PO Box 467 Sherwood Qld 4075 (07) 3277 6534 Mob 0418 878 309 [email protected] You Tube - DangerfieldDJ LIBRARY: Text Only Version 1.Circle the artists and styles that you would like played at your function, then post it to us at the above address. Your Name:_____________________________ Date of Function: ______/______/______ Job Number: #___________(from our "Booking Confirmation" & "Deposit Received" letters) 2.This list has been compiled from both our archive library and our active collections. It represents only a small portion of the estimated 10,000 titles we have available. The more obscure artists may not be in our active collections and so not be available on every function. Therefore, please forward this list to us well in advance of your function to allow us time to compile your requests. (See note at end of listings.) CLASSICAL - String Quartet - Light Classical - Baroque e.g., Handel, Pachelbel, Hayden, Vivaldi, Mozart... (Over 250 CDs to choose from) JAZZ & SWING Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Billie Holliday, Edith Piaf, Harry Connick Jnr, Vince Jones, Grace Knight, Cherry Poppin Daddies, Billy Field/Bad Habits, George Benson, Sade, Frank Sinatra, Glenn Miller, Astrud Gilberto/Girl from Ipanema, Fabulous Baker Bros, Dave Brubeck, Dave Grusen, Oscar Peterson, Manhattan Transfer.... 40's BIG BAND ERA Bing Crosby, Glen Miller, Andrews Sisters, Vera Lynn, Marlene Dietrich, Edith Piaf, Woody Herman, Benny Goodman, Mills Brothers, Tommy Dorsey, Jimmy Dorsey, Carmen Miranda, Duke Ellington, The Ink Spots, Fats Waller, Artie Shaw, Acker Bilk... CORPORATE e.g., Tom Jones, Neil Diamond, Frank Sinatra, Van Morrison, Dean Martin, Perry Como, Buena Vista Social Club.. -

'Fore She Was Mama -‐ Walker, Clay 1, 2 Step -‐ Ciara & Missy El

'Fore She Was Mama - Walker, Clay 1, 2 Step - Ciara & Missy Elliott 10 CC - Donna 10 CC - Dreadlock Holiday 10 CC - I'm Mandy 10 CC - I'm Not In Love 10 CC - Rubber Bullets 10 CC - The Things We Do For Love 10 CC - Wall Street Shuffle 10 Years - Through The Iris 10 Years - Wasteland 10 Years After - I'd Love To Change The World 10,000 maniacs - like the weather 10,000 Maniacs - More Than This 10.000 Maniacs - These Are The Days 100% Cowboy - Jason Meadows 101 Dalmatians - Cruella De Ville 112 - Cupid 112 - Dance With Me 112 - It's Over Now 112 - Only you 112 - Peaches & Cream 112 - U Already Know 12 Gauge - Dunkie Butt 1234 - Feist 15 Minutes - Atkins, Rodney 1910 Fruitgum Co - Simon Says 1910 Fruitgum Company - Simon Says.avi 1973_-_Blunt,_James 1st Time - Yung Joc Marques Houston Trey Songz 2 Become One 2 D Extreme - If I knew then 2 Live Crew - Do wah diddy 2 Live Crew - We Want Some Pussy 2 Pac - Thugz Mansion 2 Pac - Until the end of time 2 Play & Thomas Jules & Jucxi D - Careless Whisper 2 Step - DJ Unk 2 Unlimited - No Limits 20 Fingers - Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls - 21st Century Girls 26 Cents - The Wilkinsons 2O - Rapture 2O - Rapture tastes so sweet 3 Days Grace - Never Too Late 3 Degrees, The - Woman In Love 3 Doors Down - Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down - Be Like That 3 Doors Down - Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down - Duck & Run 3 Doors Down - Here Without You 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite 3 Doors Down - Landing In London 3 Doors Down - Let Me Go 3 Doors Down - Live For Today 3 Doors Down - Loser 3 Doors Down - Road I'm On 3 Doors Down - When I'm Gone 3 Of Hearts - Arizona Rain 3 Of Hearts - Love is enough 30 Seconds To Mars - Kill, The 30 Seconds To Mars - Kings & Queens 311 - All Mixed Up 311 - Don't Tread On Me 311 - First Straw 311 - Love Song 311 - You wouldn't believe 35L - Take It Easy 38 Special - Teacher, Teacher 3LW - No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3oh!3 & Ke$ha - My First Kiss 3oh!3_-_dont_trust_me 3T - Anything 3T - Tease me 4 In The Morning - Gwen Stefani 4 Non Blondes - What's Up 4 p.m. -

GYPSY LANE SONG LIST TODAY & 90'S

GYPSY LANE SONG LIST TODAY & 90's Uptown Funk (Mark Ronson/Bruno Mars) All About that Bass (Meghan Trainer) Talk Dirty (Jason Derulo) Thriftshop (Mackelmore) Fancy (IGGY) Timber (Pitbull/Keisha) Happy (Pharell Wiliams) Treasure (Bruno Mars) Blurred Lines (Robin Thicke/ Pharell) Don’t you worry child (Swedish House) Get Lucky (Daft Punk) Don’t Stop the party (Pittbull) Feel the moment (Pittbull) Girl on Fire (Alecia Keys) Gangham Style (Psy) Harlem Shake (Baauer) I Wanna Dance with Somebody/Hopeless Love (Whitney Houston/Rhianna) Mr Saxobeat (Alexandra Stan) Raise Your Glass (Pink) Good Feeling (Florider) Move like Jagger/Start me Up (Maroon 5/Mick Jagger) Rolling in the Deep/Come on Baby Light my Fire (Adele/Doors) Party Rock Anthem (LMFAO) Everything Tonight (Pittbull/Neyo) Danza Kuduro (Pittbull/Don Omar) Forget You (Ceelo) Dynamite (Tao Cruz) Billionaire (Travie McCoy) California Girls (Katie Perry) OMG (Usher) Shotz (LMFAO) How low Can You Go (Ludacris and Ciara) I Gotta Feeling (BlackEyed Peas) Boom Boom Pow (BlackEyed Peas) Beggin (Madcon) Just Dance (Lady Gaga) Pokerface (Lady Gaga) Bad Romance (Lady Gaga) Blame it on the Alcohol (Jamie Fox/ TPain) Single Ladies (Beyonce) Green light (John Legend) My Life (TI and Rhianna) Whatever you Want (TI) Dead and Gone (TI/ Justin Timberlake) Magic Girl (Robin Thicke) American Boy (Estelle/ Kanye West) Dangerous (Akon) Just Fine (Mary J Blige) World Hold On (Bob Sinclaire) Please don't stop the music (Rhianna) Only Girl in the World (Rhianna) I Kissed a Girl (Katie Perry) Low (FloRider) -

Music List (PDF)

Artist Title disc# 311 Down 475 702 Where My Girls At? 503 20 fingers short dick man 482 2pac changes 491 2Pac California Love 152 2Pac How Do You Want It 152 3 Doors Down Here Without You 452 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 201 3 doors down loser 280 3 Doors Down when I'm gone 218 3 Doors Down Be Like That 224 38 Special Hold On Loosely 163 3lw No more (baby I'm a do right) 402 4 Non Blondes What's Up 106 50 Cent Disco Inferno 510 50 cent & nate dogg 21 questions 483 50 cent & nate dogg in da club 483 5th Dimension, The aquarius/let the sunshine in 91 5th Dimension, The One Less Bell To Answer 93 69 Boyz Tootsee Roll 205 98 Degrees Because Of You 156 98 Degrees Because Of You (Dance Remix) 362 98 degrees Give me just one Night 383 98 Degrees Hardest Thing, the 162 98 Degrees I Do 162 98 Degrees My Everything 201 98 Degrees Why (Are We Still Friends) 233 A3 Woke Up This Morning 149 Aaliyah Are You That Somebody? 156 aaliyah Try again 401 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 227 Abba Dancing Queen 102 ABBA FERNANDO 73 ABBA Waterloo 147 ABC Be Near Me 444 ABC When Smokey Sings 444 ABDUL, PAULA Blowing Kisses In The Wind 446 ABDUL, PAULA Rush Rush 446 ABDUL, PAULA STRAIGHT UP 27 ABDUL, PAULA Vibeology 444 AC/DC Back In Black 161 AC/DC Hells Bells 161 AC/DC Highway To Hell 295 AC/DC Stiff Upper Lip 295 AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie 295 AC/dc You shook me all night long 108 Ace Of Base Beautiful Life 8 Ace of Base Don't Turn Around 154 Ace Of Base Sign, The 206 AD LIBS BOY FROM NEW YORK CITY, THE 49 adam ant goody two shoes 108 ADAMS, BRYAN (EVERYTHING I DO) I DO IT FOR YOU -

Audio + Video 6/22/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to Be Taken Directly to the Sell Sheet

New Releases WEA.CoM iSSUE 12 JUNE 22 + JUNE 29, 2010 LABELS / PARTNERS Atlantic Records Asylum Bad Boy Records Bigger Picture Curb Records Elektra Fueled By Ramen Nonesuch Rhino Records Roadrunner Records Time Life Top Sail Warner Bros. Records Warner Music Latina Word audio + video 6/22/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to be taken directly to the Sell Sheet. Click on the Artist Name in the Order Due Date Sell Sheet to be taken back to the Recap Page Street Date CX- ANDERSON, NON 524055 LAURIE Homeland (CD/DVD) $23.98 6/22/10 5/26/10 B.o.B Presents: The Adventures of Bobby Ray ATL A-518903 B.O.B. (Vinyl) $22.98 6/22/10 6/2/10 The Great Ray Charles (180 ACG A-1259 CHARLES, RAY Gram Vinyl) $24.98 6/22/10 6/2/10 CD- TSG 25486-D CHESNUTT, MARK Outlaw $17.98 6/22/10 6/2/10 REP A-47736 CLAPTON, ERIC August (Vinyl) $22.98 6/22/10 6/2/10 Coltrane Jazz (180 Gram ACG A-1354 COLTRANE, JOHN Vinyl) $24.98 6/22/10 6/2/10 Plays The Blues (180 Gram ACG A-1382 COLTRANE, JOHN Vinyl) $24.98 6/22/10 6/2/10 CX- LYNYRD Live From Freedom Hall RLP 177815 SKYNYRD (CD/DVD) $24.98 6/22/10 5/26/10 DV- LYNYRD RLP 109169 SKYNYRD Live From Freedom Hall (DVD) $14.99 6/22/10 5/26/10 ROBERT CD- RANDOLPH & THE WB 511230 FAMILY BAND We Walk This Road $13.99 6/22/10 6/2/10 CD- SMITH, AARON MFL 524761 NIGEL Everyone Loves To Dance $13.98 6/22/10 6/2/10 CD- NEK 524367 UFFIE Sex Dreams and Denim Jeans $13.99 6/22/10 6/2/10 CD- MFL 524463 VARIOUS ARTISTS Giggling & Laughing $13.98 6/22/10 6/2/10 CD- FBY 524346 VERSA EMERGE Fixed At Zero $13.99 6/22/10 6/2/10 -

The Leading Ladies of Popular Music: an Assessment of Lyrical Content Julie Miller

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Honors Theses University Honors Program 12-2001 The Leading Ladies of Popular Music: An Assessment of Lyrical Content Julie Miller Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/uhp_theses Recommended Citation Miller, Julie, "The Leading Ladies of Popular Music: An Assessment of Lyrical Content" (2001). Honors Theses. Paper 96. This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. , • • • Clh.e -feculm;) -fadk~ ofgJopufa~eMu~w: • o'fn cffHeHm£nt of1:yUaafContent • • • • • • Julie Miller • • • • • December 12, 2001 • • • • University Honors Thesis • • • • • • • • • • • • • Forward • • There is a story ofwomen in music history, similar to that ofwomen in work, • women in the family or women in society. This is a woman's story of oppression and • silencing not unlike many of its predecessors. In modem elementary school music • classes, ofthe ones that are left, the teacher usually fails to mention why women are • almost entirely left out when they study classical music. It is a matter ofwhat is left • unsaid. I studied classical piano as a child for thirteen years and until I got to college I • never once thought about why all of the composers I mimicked were men. From the very • beginning ofwhat we call modem music, there were rules and restrictions placed upon • what women may and may not do with their musical talent. • Within modem music in Europe, women were included in musical education and • were allowed to practice their talents.