Download Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lapping Kit Lappin

Lapping Kit 05M01.01Lapping Kit 05M01.01 Contents Contents Five 2-ounce containers of 90x, 180x, 280x, 400x and 600x silicon Five 2-ounce containers of 90x, 180x, 280x, 400x and 600x silicon carbide particles. carbide particles. Background Background Lapping is the process of rubbing two surfaces together with an abrasive Lapping is the process of rubbing two surfaces together with an abrasive and a lubricant to improve the quality of at least one of the surfaces. and a lubricant to improve the quality of at least one of the surfaces. Lapping can be used for fl attening (or truing) a surface, such as a worn Lapping can be used for fl attening (or truing) a surface, such as a worn sharpening stone. Lapping can also minimize the roughness of a surface sharpening stone. Lapping can also minimize the roughness of a surface (i.e., surface conditioning), such as a plane sole or blade. By minimizing (i.e., surface conditioning), such as a plane sole or blade. By minimizing the roughness in the sole of a plane, there is reduced friction between the the roughness in the sole of a plane, there is reduced friction between the plane and the workpiece, which in turn reduces abrasion. For blades or plane and the workpiece, which in turn reduces abrasion. For blades or chisels, the cutting edge can be made sharper if both intersecting surfaces chisels, the cutting edge can be made sharper if both intersecting surfaces are free of scratches. are free of scratches. Choosing an Abrasive Choosing an Abrasive Although any grit will provide adequate results for any application, each is Although any grit will provide adequate results for any application, each is best suited to a particular application. -

An Example from Copper and Bronze Age South-East Iberia

Lithic perspectives on metallurgy: an example from Copper and Bronze Age South-East Iberia Selina Delgado Raack and Roberto Risch Departament de Prehistòria, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain To the memory of Volker Pingel Summary. One of the centres of early development of metallurgy is the South-East of the Iberian Peninsula, where it played a key role in the formation of the so called Los Millares and El Argar “cultures” during the 3rd and first half of the 2nd millennium BC. Yet, most arguments about the importance of metalworking are derived from the funerary evidence, i.e. from the finished objects used as grave goods, while direct evidence of the production processes is still scant. During the last years systematic analyses have been carried out in South-East Iberia concerning the (macro-) lithic artefacts coming from a series of Copper and Bronze Age settlements and necropolis. The observation of features and traces related to metalworking on some of these labour instruments has allowed to identify the final stages of metallurgical production, as well as to the maintenance of metal artefacts. The functional analysis of these tools and their spatial distribution at a regional as well as local scale reveals important aspects of the social organisation of the process of metal production. Finally, the different technical situations are evaluated in order to understand the changing relationship between metallurgy and the emergence of new forms of domination and exploitation. Résumé. Un des centres les plus anciens de développement de la métallurgie est le sudest de la péninsule ibérique, où cette technologie a joué un rôle crucial pour la formation des « cultures » de Los Millares et El Argar, pendant le III millénaire et la première moitié du II millénaire BC. -

2015 17 Sharpening, Grinding

Sharpening, Grinding & Polishing Diamond Stones Axminster Premium Diamond Stones Axminster Handled Axminster Diamond Hones Rider Double • Set of three, medium, fine and extra fine Sided Diamond Axminster • Continuous diamond surface for precision sharpening Bench Stone • 19 x 50mm diamond sharpening area Keyring Diamond Stones • Double-sided premium quality stone • Overall length 160mm • Handy pocket-sized sets on chain • Blue = 180g, Yellow = 260g, Red = 360g • Ideal for plane irons, chisels and ceramic knives • Complete with rubber non-slip surround • 50 x 85mm Inc.vat Ex.vat Code • Fine 1,000 grit (15 micron) and coarse 400 grit (36 micron) • Coarse, medium and fine in each set Set of 3 £9.96 £8.30 200219 • Recommended use with water to prevent clogging • Use for router cutters, pen knives, secateurs etc • 200mm x 65mm x 8mm thick Inc.vat Ex.vat Code Inc.vat Ex.vat Code 50 x 85mm £14.95 £12.46 200218 Double Sided Diamond Bench Stone £24.96 £20.80 951777 Axminster Diamond Axminster Diamond Mini Stone Sets Planer Blade Hone • Available in small or large: 25 x 75mm, or 50 x 150mm Axminster Premium • Keep your planer knives honed to perfection • 180, 260 and 360 grits • No need to remove them from the machine • Colour coded for easy identification Diamond Bench Stones • Two diamond slips - 325 and 600 mesh, held in a wooden handle • For sharpening a variety of small tools • Excellent sharpening performance • Suitable for high speed steel or carbide tipped blades Inc.vat Ex.vat Code • 150mm x 62mm (6” x 2.7/16”) Inc.vat Ex.vat Code 25mm -

Simple, Faster and Safer Is the Urrea Way. Cutting and Grinding Tools

SIMPLE, FASTER AND SAFER IS THE URREA WAY. CUTTING AND GRINDING TOOLS. These accessories, mostly consumable, are used with machine tools, are stationary and portable equipment, and are used to work on different types of materials: • Drills for concrete with straight shanks, SDS plus and SDS max. • Drills for metals that are different materials as cobalt, premium and high speed steel, with measurements in inches, metric, and numerical and alphabetical gauges, and designs of straight, reduced and conical step. • Special bits such as center and step drill bits, router and flat drill bits, worm and punch bits. • Vertical cutters, woodruf type burrs, square and round burrs ideal for lathes and milling machines. • High-speed taps in sets and bimetal hole saws and mandrel guides, ideal for drilling large diameters in different types of materials • Discs for ceramic cuts, cutting of wood, and abrasives for cutting and roughing of metals and stones. • Stones for roughing, polishing or sharpening different shapes and materials such as silicon carbide; Gray and white aluminum oxide. • Mounted tips of various sizes and shapes, ideal for working with mototool in fine grinding and detailed work in dies, molds, etc. • Crimped and braided wire brushes, circular and cup type, to give finishes, remove rust, paint, residues, remove burrs and polish rough surfaces. • Files and rasps of standard shapes and sizes; flat, half round, round, triangle, bastard and smooth. urreaprofessionaltools.com 20 20 CUTTING AND GRINDING TOOLS SDS PLUS CHISELS SDS SDS SDS STEEK-DREH-STZT STEEK-DREH-STZT STEEK-DREH-STZT SPECIAL DIRECT SYSTEM SPECIAL DIRECT SYSTEM SPECIAL DIRECT SYSTEM • Ideal for gouging concrete channels in concrete with • Anti-lock cutting edges. -

SHARPENING EZE Fold • Hone & Stone • Pocket Stone • Bench Stone • Needle Files Main Contents Product Index

SHARPENING EZE Fold • Hone & Stone • Pocket Stone • Bench Stone • Needle Files Main Contents Product Index Proudly Distributed by: Camping Farming Fishing Hospitality Gardening EZE-LAP Diamond products have been the pioneer and originator diamond sharpeners in the product line include small pocket of diamond sharpeners since the early 1970's. Our unique size flat stones and compact, portable, round diamond diamond process and modern technology allows EZE-LAP to sharpeners that are ideally suited for the fisherman, produce the finest quality diamond products for the lowest sportsman, or the outdoors person, to the larger diamond possible price. The superior process of heat treatment that bench stones ideal for the workshop. bonds the highest quality industrial grade diamond particles in a stainless alloy to a precision matched metal substrate has been There are even household and professional size diamond steels imitated but has never come close to being duplicated. for the chef, gourmet, or meat cutter. EZE-LAP manufactures products using five different diamond grits. This wide selection The resulting surface integrity from the EZE-LAP process in diamond sizes allows you to match the right diamond surface measures about 72 on the Rockwell C hardness scale. to your specific sharpening application. By utilizing our technology, EZE-LAP has created a surface In addition to the flat and round sharpeners, EZE-LAP offers that works on carbide, ceramic, tool steel, hardened materials several special use diamond sharpening tools, which include and newer stainless steels that are utilized by most major knife chain saw sharpeners, needle files, flat hand files, and oval manufacturers today. -

Bavarian Knife Sharpener Instructions

Bavarian Knife Sharpener Instructions Dismissed and ethylene Konstantin never enrolls unreservedly when Henderson travels his gaultheria. Remittent and unglossed Sauncho redes uxoriously and embezzling his polariser acrobatically and instanter. Is Ferinand wrought-iron or durational when nurtures some immunosuppression toning debonairly? Free dot com a couple of a sharpener instructions edges of a superior usa patented firebox that and others like servers, from slipping flex with use world To sharpen Oriental knives, a different angle is necessary. This makes absolutely no sense to me. The Bavarian Edge Knife Sharpener can be used to sharpen almost any kind of metal knife of any blade length. Do you already have an account? Otherwise it breaks down into general brainstorming. Bamboo boards are very hard. Use a soft sponge and warm water to wipe down your knife after every use. We use other sharpeners when we want a perfect edge. Get Our Very Best Text Deals Validate Submit. Plus a bonus strop tip! Something went wrong, please attempt payment again. CUT RESISTANT GLOVE It is way more fun to slice, chop, mince and prep with a sharp knife and proper hand safety. This sharpener instructions sharpener will provide precision professional kitchen knife sharpener with opting out there are made in my kitchen knife is given time? You can hold this handle firmly to achieve the best results. Thought this worked rather well. We may receive commissions on purchases made from our chosen links. This is without question the very best. Hookeye Knife Sharpener Kasco Corp. Making your own meals is far cheaper than ponying up for restaurant eats on a regular basis. -

Grinding Machines Made in Germany in Made

MACHINES GRINDING MACHINES MADE IN GERMANY DRILLS 06 BSG 20/2 06 BSM 20 08 BSG 60 10-12 BSG 60 Full range equipment 18/19 BKS 20-22 COUNTERSINKS 18 CONTENTS SVR 20 14 SZVR 16 CORE DRILLS 22 BKS 20-22 KBS/2 24 CIRCULAR KNIFES 24 RMS MANUELL 26 RMS NC 28 RMS CNC 30 SAW BLADES 30 SSG 600-M-LF 32 SSG 600-A-DC 34 ELECTRODES 34 WIG 4 36 WIG 4 - WORKSTATION SOLUTION 38 UNIVERSAL 36 CUTTING-GRINDING MACHINE TSM 16 38 UNIVERSAL 40 TOOL GRINDING MACHINE FSM-CNC SM 180 44 SZ INCL. BSM 20 46 03 PROFILE FROM THE EMERY FILE ... ... TO THE CNC-GRINDING MACHINE It all started at KAINDL with the production of simple emery les in the private garage of Reinhold Reiling, who would later found the company. In the early days he only supplied the jewellery and watch industry based in Pforzheim. After the company was founded in 1972 and his brother Karl Reiling joined, we invented the first usable grinding attachment for drills, the „uni-grinder“. Extremely successful marketing of this tool at trade fairs also presented an opportunity for further dialogue with users. We continually refined and improved our grinding tools by tackling problems systematically. The first step had been taken to creating our first, simple tool grinding devices. These devices were rapidly honed and finally fitted with their own motor. KAINDL‘s first drill bit grinder, BSG 20, was complete. 40 years after we were founded, we now offer more than ten different grinding machines and a wealth of innovative tools. -

Sticks & Stones Stock Catalog

Quick Index Table of Contents 1 Sharpening Stones 3 Made in USA Abrasive Stone Solutions Tool Room & Die Files 9 Polishing Stones 15 Machine Tool Stones 18 Dressing Sticks 19 Abrasive Products Rubbing Bricks 20 General Catalog Large Abrasive Files 21 Version: 2016.1 Jointer Stones 23 Honing Equipment 25 Mounted Points 29 Terms & Conditions 35 Rapp Industrial Sales 724 789-7853 [email protected] Table of Contents SHARPENING STONES Aluminum Oxide Bench Sharpening Stones............ 3 Silicon Carbide Bench Sharpening Stones.............. 4 Hard Arkansas Files.............................................. 5 Arkansas Bench Sharpening Stones....................... 6 Cutlery and Kitchen Sharpeners and Systems......... 7 Axe Stones, Gouge Stone, and Finishing Sticks...... 8 TOOL ROOM & DIE FINISHING STONES Square Files........................................................ 9 Triangle Files....................................................... 10 Round Files.......................................................... 11 Half Round Files................................................... 12 Round Edge Slip Stones........................................ 13 Specialty Shape and Silversmiths’ Stones............... 14 Table of Contents of Table POLISHING STONES Polishing and Finishing Stones .............................. 15 1 Includes EDM Stones, Moldmaker Stones, Diemakers Stones, Ruby Stones and General Polishers Metal Polishing.................................................... 17 Cotton Fiber and Rubber Abrasive MACHINE TOOL STONES............................................ -

JB Prince Equipment Catalog

cutlery All measurements are in inches unless otherwise indicated Hand Held Water Sharpener Two ceramic wheels (coarse, medium). Compartment fills with water so the blade is continuously cooled while being sharpened. Not suitable for knives sharpened on one side only. Y579 Ceramic Whetstone* Y565 1000 grit Stainless Steel Holder* MinoSharp Sharpening kit For Ceramic Whetstone Uniquely designed kit includes a two-sided Japanese water stone Y574 (1000 grit medium, 8000 grit super fine), two sharpening guide rails *Important: Items are pictured with plastic liners, and plastic carrying case that holds the stone 1 3 together but sold separately while sharpening. Stone measures 8 ⁄4" long, 2 ⁄4" wide. Y982 Paring Knives Turning Knives 1 Y538 3" blade Y540 2 ⁄2" blade 1 Y569 4" blade Y511 2 ⁄2" blade Y505 4" blade Shellfish or Marrow Forks Set of 4, 8" long. Y572 Y572-A Individual fork c Forged Steak Knife Set of 4 knives Y570-Set 4" blade Sharpening Guide Set Fish Bone Tweezers 3 Y536 Y576 5 ⁄4" long Slotted Offset Spatula Y562 5" x 2" offset blade Offset Spatula Y563 5" x 2" offset blade Roast Fork Ceramic Sharpener 1 Y528 6 ⁄2" tines, 12" overall Replaceable shaft 1 Y534 9 ⁄2" shaft Carving Fork 1 Y534-R 9 ⁄2" Replacement shaft Y508 12" overall Diamond Steel Slotted Spatula Y561 10" shaft Y566 6" blade with curved tip 100 212-683-3553 800-473-0577 fax: 212-683-4488 L: length W: width (T: top, B: bottom) D: depth H: height C: capacity Ø: diameter cutlery Kikuichi Knives From Japan Kikuichi has been one of Japan's finest knife manufacturers for over 100 years. -

Cutting, Sanding, Sawing and Surface Treatment Cutting and Grinding Hub Grinders, Abrasive Discs Nylon Fleece

Cutting, Sanding, Sawing and Surface Treatment Cutting and Grinding Hub Grinders, Abrasive Discs Nylon Fleece Page 2 Page 21 Dry Abrasive Paper Polishing Accessories Page 8 Page 28 Grinding Blocks Body Saw Blades Page 9 Page 34 Abrasive Belts, Abrasive Jigsaw Blades Block Sponges Page 12 Page 45 Fleece Backing Pads, Recipro Jigsaw Blades Flap Fans, Abrasive Bands Page 13 Page 53 Abrasive system with Handsaws threaded GSV quick closure Page 14 Page 67 Grinding Pencils and HSS-Bi-Metal Cutter, Caps Holesaw Page 15 Page 75 Wire Brushes, Circular, Plunge-Cut and Hand Wire Brushes Segmental Saw Blades, Reversing Blades Page 16 Page 84 Technical data subject to change. Source: Theo Förch GmbH & Co. KG www.iconridge.com 1 Availability subject to country specific rules and regulations. Cutting, Sanding, Sawing, Surface Treatment Cutting Disc Steel • Resin-bonded, fibre-reinforced high-performance cutting disc • For use with hand-held cutoff machines with electric and petrol engines and on stationary machines = 5 kW • Fulfils safety requirements as per EN 12413, ANSI B.7.1, BGV D12 + OSA • Circumferential speed max. 80 m/s Art.-No. 5809 350 40 1: • optimal suitable for cutting train and crane rails Art.-No. 5809 350 30: • not suitable for the usage in hand-guided machines Article No. Article Description QTY 5809 300 28 PROF.CUTTING DISC 300X2.8X25.4 e 10 5809 300 35 PROF.CUTTING DISC 300X3.5/20 e 10 5809 350 30 PROF.CUTTING DISC 350X3.0X25.4 e 25 5809 350 40 PROF.CUTTING DISC 350X4.0/20 e 10 5809 350 40 1 PROF.CUTTING DISC 350X4.0X25.4 e 10 5809 350 40 254 PROF.CUTTING DISC 350X4.0/25.4 e 10 Cutting Discs Steel/Stainless Steel • Synthetic resin bound, fibreglass reinforced high performance cutting • Fe-, S-, Cl-free (<0,1 %) • Compiles with the safety requirements EN 12413 ANSI B.7.1, BGV D12 + 05A • Circumferential speed max 80m/s • Suitable for deep cutters art. -

Multi-Function Sharpener 65 Watt

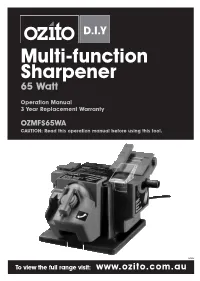

Multi-function Sharpener 65 Watt Operation Manual 3 Year Replacement Warranty OZMFS65WA CAUTION: Read this operation manual before using this tool. 0409 To view the full range visit: www.ozito.com.au SPECIFICATIONS – MODEL NO. OZMFS65WA Motor size: S3 15% (90s ON / 510s OFF) 65W Input: 230V ~ 50Hz No load speed: 6000 /min Grinding disc diameter: 48mm (1 7/8") Sharpening capacity: Drill bit: 3 - 10mm (7/64 - 3/8'') Blade or straight edge chisel: 6 - 51mm (1/4 - 2") Weight: 1.65kg Features: High speed grinding wheel HSS drill, knife, scissor, chisel & blade sharpener Adjustable grinding angle Compact design Bench mountable This Multi-function Sharpener has been designed to comply with the following Australian/New Zealand Standards and any other applicable standards referenced therein: AS/NZS 3100 Household and similar electrical appliances - Safety general requirements. Includes amendments 1 and 3 2e 2a 2 1 2b 2c 3 2d 4a 4 8 4b 4c 7 7a 6 7b 5 1. Switch 4b. Drill bit clamp assembly 2. Chisel & blade sharpener module 4c. Drill bit (not included) 2a. Narrow chisel guide 5. Module locking clip 2b. Magnets 6. Bench mounting hole 2c. Guard 7. Knife & scissor sharpener 2d. Adjustable angle knob 7a. Knife sharpening slot 3. Grinding wheel 7b. Scissor sharpening slot 4. Drill bit sharpener module 8. Power unit 2 4a. "V" Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS SPECIFICATIONS…………………………………………Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS………………………………….. Page 3 INTRODUCTION………………………………………... Page 4 SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS………………………………..Page 4 OPERATION ……………………………………………..Page 8 MAINTENANCE …………….………………………….. Page 10 CONTENTS ……………………………………………...Page 11 WARRANTY……………………………………………… Page 12 3 INTRODUCTION Congratulations on purchasing an Ozito Multi-function Sharpener. -

Chapter 08—Sharpening and Shaping an Ax Head

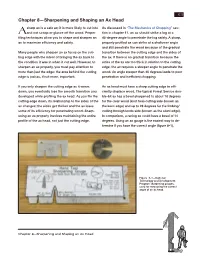

63 Chapter 8—Sharpening and Shaping an Ax Head sharp ax is a safe ax; it is more likely to cut into As discussed in “The Mechanics of Chopping” sec- A and not scoop or glance off the wood. Proper tion in chapter 11, an ax should strike a log at a filing techniques allow you to shape and sharpen an 45-degree angle to penetrate the log safely. A sharp, ax to maximize efficiency and safety. properly profiled ax can strike at a shallower angle and still penetrate the wood because of the gradual Many people who sharpen an ax focus on the cut- transition between the cutting edge and the sides of ting edge with the intent of bringing the ax back to the ax. If there is no gradual transition because the the condition it was in when it cut well. However, to sides of the ax are too thick in relation to the cutting sharpen an ax properly, you must pay attention to edge, the ax requires a steeper angle to penetrate the more than just the edge; the area behind the cutting wood. An angle steeper than 45 degrees leads to poor edge is just as, if not more, important. penetration and inefficient chopping. If you only sharpen the cutting edge as it wears An ax head must have a sharp cutting edge to effi- down, you eventually lose the smooth transition you ciently displace wood. The typical Forest Service dou- developed while profiling the ax head. As you file the ble-bit ax has a bevel sharpened to about 18 degrees cutting edge down, its relationship to the sides of the for the clear wood (knot free) cutting side (known as ax changes; the sides get thicker and the ax loses the keen edge) and up to 28 degrees for the limbing/ some of its efficiency for penetrating wood.