Ireland in a Warmer World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

451Research- a Highly Attractive Location

IRELAND A Highly Attractive Location for Hosting Digital Assets 360° Research Report SPECIAL REPORT OCTOBER 2013 451 RESEARCH: SPECIAL REPORT © 2013 451 RESEARCH, LLC AND/OR ITS AFFILIATES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ABOUT 451 RESEARCH 451 Research is a leading global analyst and data company focused on the business of enterprise IT innovation. Clients of the company — at end-user, service-provider, vendor and investor organizations — rely on 451 Research’s insight through a range of syndicated research and advisory services to support both strategic and tactical decision-making. ABOUT 451 ADVISORS 451 Advisors provides consulting services to enterprises, service providers and IT vendors, enabling them to successfully navigate the Digital Infrastructure evolution. There is a global sea change under way in IT. Digital infrastructure – the totality of datacenter facilities, IT assets, and service providers employed by enterprises to deliver business value – is being transformed. IT demand is skyrocketing, while tolerance for inefficiency is plummeting. Traditional lines between facilities and IT are blurring. The edge-to-core landscape is simultaneously erupting and being reshaped. Enterprises of all sizes need to adapt to remain competitive – and even to survive. Third-party service providers are playing an increasingly flexible and vital role, enabled by advancements in technology and the evolution of business models. IT vendors and service providers need to understand this changing landscape to remain relevant and capitalize on new opportunities. 451 Advisors addresses the gap between traditional research and management consulting through unique methodologies, proprietary tools, and a complementary base of independent analyst insight and data-driven market intelligence. 451 Research leverages a team of seasoned consulting professionals with the expertise and experience to address the strategic, planning and research challenges associated with the Digital Infrastructure evolution. -

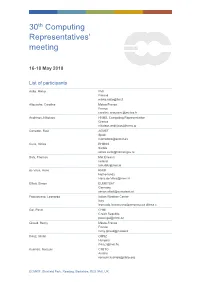

30Th Computing Representatives' Meeting

30th Computing Representatives’ meeting 16-18 May 2018 List of participants Aalto, Mikko FMI Finland [email protected] Allouache, Caroline Meteo France France [email protected] Andritsos, Nikolaos HNMS, Computing Representative Greece [email protected] Corredor, Raul AEMET Spain [email protected] Curic, Sinisa RHMSS Serbia [email protected] Daly, Thomas Met Éireann Ireland [email protected] de Vries, Hans KNMI Netherlands [email protected] Elliott, Simon EUMETSAT Germany [email protected] Facciorusso, Leonardo Italian Weather Center Italy [email protected] Gal, Pavel CHMI Czech Republic [email protected] Giraud, Remy Météo-France France [email protected] Ihasz, Istvan OMSZ Hungary [email protected] Kushida, Noriyuki CTBTO Austria [email protected] ECMWF, Shinfield Park, Reading, Berkshire, RG2 9AX, UK Langer, Matthias ZAMG Austria [email protected] Magnússon, Garðar Þór Icelandic Met Office Iceland [email protected] Malovic, Vladimir DHMZ Croatia [email protected] Melanitis, Dimitra Royal Meteorologic Institute Belgium [email protected] Milton, Roger Met Office United Kingdom [email protected] Ostroveanu, Catalin National Meteorological Administration Romania [email protected] Pejcoch, Martin Grønlien MET Norway Norway [email protected] Reiter, Manuel Deutscher Wetterdienst Germany [email protected] Spaniel, Oldrich SHMU Slovakia [email protected] Speranza, Luciano Italian Weather Center (Air Force) Italy [email protected] -

ECMWF 41R2 Press Release

PRESS RELEASE 10 MARCH 2016 EUROPEAN MEDIUM-RANGE WEATHER FORECAST MODEL UPGRADED TO BEST EVER • More accurate global weather predictions at record-breaking resolution • Number of grid points tripled to 900 million, evenly distributed around the globe • Gain in predictability of up to half a day at same level of quality Years of scientific and technical work came to fruition today as the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) launched a significant set of upgrades, dramatically increasing the quality of both its high-resolution and its ensemble forecasts. The changes nearly halve the distance between global weather prediction points, substantially increasing the effective resolution of the final forecast. As a result, ECMWF’s numerical weather predictions, which are widely used by Europe’s meteorological services, are more accurate than they have ever been before. These model upgrades represent a huge leap forward for ECMWF’s 34 Member and Co- operating States, giving National Meteorological Services access to higher resolution and improved data to help them deliver weather forecast services. Europe’s weather can now be predicted with more detail, with greater accuracy, and as a result, up to half a day further ahead. The upgrades are set to offer improved range, reliability and accuracy to provide earlier warnings of adverse conditions and extreme weather to help protect property and vital infrastructure, and to aid long-term planning for weather-dependent industries. Speaking for Météo-France, Nicole Girardot commented: “The ECMWF upgrade to its model resolution represents a significant step. The advances brought by this new version will allow Météo-France to improve the quality of its own forecasts and the wind forcing for warnings of poor air quality and dangerous conditions at sea. -

A Life Cycle Assessment Approach on Swedish and Irish Beef Production

Life Cycle Analysis – HT161 December 2016 A life cycle assessment approach on Swedish and Irish beef production Group 1 - Emma Lidell, Elvira Molin, Arash Sajadi & Emily Theokritoff 0 AG2800 Life cycle assessment Lidell, Molin, Sajadi, Theokritoff Summary This life CyCle assessment has been ConduCted to identify and Compare the environmental impacts arising from the Swedish and Irish beef produCtion systems. It is a Cradle to gate study with the funCtional unit of 1 kg of dressed weight. Several proCesses suCh as the slaughterhouse and retail in both Ireland and Sweden have been excluded since they are similar and CanCel each other out. The focus of the study has been on feed, farming and transportation during the beef production. Since this is an attributional LCA, data ColleCtion mainly Consists of average data from different online sources. Smaller differenCes in the Composition of feed were found for the two systems while a major difference between the two production systems is the lifespan of the Cattle. Based on studied literature, the average lifespan for Cattle in Sweden is 45 months while the Irish Cattle lifespan is 18 months. The impaCt Categories that have been assessed are: Climate Change, eutrophiCation, acidifiCation, land oCcupation and land transformation. In all the assessed impact categories, the Swedish beef produCtion system has a higher environmental impact than the Irish beef produCtion system, mainly due to the higher lifespan of the cattle. AcidifiCation, whiCh is the most signifiCant impact Category when analising the normalised results, differs greatly between the two systems. The Swedish beef system emits almost double the amount (1.3 kg) of SO2 Eq for 1 kg of dressed weight Compared to the Irish beef system (0.7 kg SO2 Eq/FU). -

UCC Library and UCC Researchers Have Made This Item Openly Available

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title The historic record of cold spells in Ireland Author(s) Hickey, Kieran R. Publication date 2011 Original citation HICKEY, K. 2011. The historic record of cold spells in Ireland. Irish Geography, 44, 303-321. Type of publication Article (peer-reviewed) Link to publisher's http://irishgeography.ie/index.php/irishgeography/article/view/48 version http://dx.doi.org/10.2014/igj.v44i2.48 Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2011 Geographical Society of Ireland http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/2526 from Downloaded on 2021-10-04T01:15:21Z Irish Geography Vol. 44, Nos. 2Á3, JulyÁNovember 2011, 303Á321 The historic record of cold spells in Ireland Kieran Hickey* Department of Geography, National University of Ireland, Galway This paper assesses the long historical climatological record of cold spells in Ireland stretching back to the 1st millennium BC. Over this time period cold spells in Ireland can be linked to solar output variations and volcanic activity both in Iceland and elsewhere. This provides a context for an exploration of the two most recent cold spells which affected Ireland in 2009Á2010 and in late 2010 and were the two worst weather disasters in recent Irish history. These latter events are examined in this context and the role of the Arctic Oscillation (AO) and declining Arctic sea-ice levels are also considered. These recent events with detailed instrumental temperature records also enable a re-evaluation of the historic records of cold spells in Ireland. -

Page 1 of 22 Last Name First Name Affiliation Country A. Pastor Maria

EMS2019: list of participants who agreed to have their name published on-line (version of 13 September 2019, 11:30 CEST) Last name First name Affiliation Country A. Pastor Maria AEMET Spain Aaltonen Ari Finnish Meteorological Institute Finland Akansu Elisa Deutscher Wetterdienst Germany Albus-Moore Alexandra EUMETNET Belgium Altava-Ortiz Vicent SMC-Meteorological Service of Catalonia Spain Alvarez-Castro Carmen FONDAZIONE CMCC Italy Amorim Inês University of Porto, Portugal Portugal Andersen Henrik Steen European Environment Agency Denmark Andrade Cristina Polytechnic Institute of Tomar, NHRC.ipt Portugal Andreas Dahl Larsen Morten Technical University of Denmark Denmark Andrée Elin Technical University of Denmark Denmark Andrews Martin Met Office Hadley Centre United Kingdom Aniśkiewicz Paulina Institute of Oceanology PAN Poland Asgarimehr Milad German Research Centre for Geosciences Germany Audouin Olivier Météo France, CNRM France Badger Jake Technical University of Denmark Denmark Bange Jens University of Tübingen Germany Barantiev Damyan CAWRI-BAS Bulgaria Baronetti Alice University of Turin Italy Barrett Bradford U.S. Naval Academy United States Barry James University of Heidelberg Germany Båserud Line Norwegian Meteorological Institute Norway Batchvarova Ekaterina CAWRI-BAS Bulgaria Bazile Eric Météo-France/CNRS CNRM-UMR3589 France Beljaars Anton ECMWF United Kingdom Bell Louisa Climate Service Center Germany, HZG Germany Benassi Marianna CMCC FOUNDATION Italy Benestad Rasmus Norwegian Meteorological Institute Norway Benson Randall -

11.1 How to Make an International Meteorological Workstation Project Successful

11.1 HOW TO MAKE AN INTERNATIONAL METEOROLOGICAL WORKSTATION PROJECT SUCCESSFUL Hans-Joachim Koppert 1 Deutscher Wetterdienst, Offenbach, Germany Torben Strunge Pedersen Danish Meteorological Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark Bruno Zürcher MeteoSwiss, Zürich, Switzerland Paul Joe Meteorological Service of Canada, Toronto, Canada 1. INTRODUCTION partners. In the course of the project, they are refined when the respective sub-project work- The Deutsche Wetterdienst (DWD) together packages are initiated. with the German Military Geophysical Service (GMGO) started a new Meteorological Workstation project (NinJo) in 2000. Soon thereafter Meteo- Swiss and the Danish Meteorological Institute (DMI) joined the project. Just recently, the Meteorological Service of Canada (MSC) decided to become a member of the NinJo consortium. The aim of the project is to replace aging workstation systems (Kusch 1994, Koppert 1997) and to provide an unified environment to support forecasting and warning operations. Besides the development of new, or the integration of recently developed applications, it is necessary to provide most of the capabilities of the existing systems. Forecasters are conservative and often would like to stay with their old tools. So we are facing an enormous pressure to implement a system that does (nearly) everything better. Since NinJo is a multi-national project with 5 Figure 1: A NinJo window with 3 scenes: gridded partners, diverse hardware and software infra- data (left), surface observations ( top right), satellite structures, distributed development sites, and local image (bottom right) meteorological needs, a strong requirement is to built the software with a sound software architecture The following list shows NinJo’s main features : that could easily be adapted to the needs of the partners. -

DVAS - Data Visualization and Analysis Software: Processing and Analysis of the Radiosonding Data for the Next WMO Upper-Air Instruments Intercomparison UAII2021

Federal Department of Home Affairs FDHA Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology MeteoSwiss DVAS - Data Visualization and Analysis Software: processing and analysis of the radiosonding data for the next WMO Upper-Air Instruments Intercomparison UAII2021 Frédéric P.A. Vogt1, Giovanni Martucci1, Ruud Dirksen2, Gonzague Romanens1, Luca Modolo1, Alexander Haefele1, Michael Sommer2, Christian Félix1, Volker Lehmann2, Holger Voemel3, David Edwards4, Stewart Taylor5, Tom Gardiner6, Mohd. Imran Ansari7, Emad Eldin Mahmoud8, Tim Oakley9, Isabelle Ruedi9, Krunoslav Premec9, Franz Berger2, and Bertrand Calpini1 1 - MeteoSwiss, Payerne, Switzerland ([email protected]); 2 - Lindenberg Meteorological Observatory, Deutscher Wetterdienst, Lindenberg, Germany; 3 - University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, UCAR, Boulder, CO, USA; 4 - Met office, Exeter, United Kingdom; 5 - EUMETNET; 6 - National Physical Laboratory (NPL), Hampton Road, Teddington, TW11 0LW Middlesex, UK; 7 - Indian Meteorological Department (IMD), Delhi, India; 8 - Egyptian Meteorological Authority, Cairo, Egypt; 9 - World Meteorological Organization (WMO), Geneva, Switzerland D701 ¦ EGU2020 -17779 ¦ 07.05.2020 1 WMO Upper-Air Instruments Intercomparison UAII2021 What: international comparison of upper-air instrument performances. Based on laboratory radiosonde test measurements, and multi-payload radiosonde flights in combination with ground-based remote sensing and in-situ aircraft measurements. When & Where: December 2020 (lab); August 2021 (flights) @ Lindenberg, Germany. Who: DWD (lead), MeteoSwiss, under the auspices of the WMO. Primary goals: 1. To test and evaluate as many operational radiosonde systems as possible at the same location and time. 2. To characterize the individual radiosondes with respect to their reproducibility and to determine the uncertainty of the different measured parameters. 3. To compare the different radiosonde systems to characterized reference systems employed in the GCOS Reference Upper Air Network (GRUAN). -

DWD's Climate Services Help to Adapt to Climate Change As Well As Possible

2010s 2000s 1990s 1980s 1970s 1960s 1950s DWD’s Climate Services Observing – Modelling – Consulting Foreword Dear readers, Climate change presents us with great challenges. Extreme weather events and changes in the climate can cause humanitarian disasters and huge damage to the environment. Decision-makers in politics, administration and business require meaningful information about the changing climate and the climate of the future to be able to develop preventive measures against the consequences of climate change. There is therefore demand for high spatial resolution information as well as information for specific fields of action, such as water management and health. The Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD) regards the provision of climate information as a comprehen- sive and user-oriented service. The DWD has the biggest climate data collection in the whole of Germany and offers many years of experience in climate monitoring, climate modelling on different space and timescales and model result evaluation. The DWD is also well networked with other scientific institutions at the national and international level and ensures that customers are given state-of-the-art scientific information. Besides supplying data and information on various portals, a key aspect of our mission is communicating directly with and providing consultancy services to our customers. This also helps enhance users’ capability to use climate data in various areas of application. The DWD also assists in the development of climate services in other countries, including, in particular, developing countries. All these activities take account of the elements for successful climate services recommended by the Global Framework for Climate Services. Our aim in publishing this brochure is to provide a readable overview of all the climate services provided by the DWD. -

The Model Chain of the Deutscher Wetterdienst and Its Use in Operational Weather Forecasting

THE MODEL CHAIN OF THE DEUTSCHER WETTERDIENST AND ITS USE IN OPERATIONAL WEATHER FORECASTING M. KURZ Head , Department of Weather Forecasting, DWI) INTRODUCTION According to law the Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD) has to guarantee the meteorological safety of air and sea navigation. The DWD has also to provide forecast information for a wide variety of users including the public, private enter- prises and media. These tasks are carried out in the business area ,Forecast Cus- tomers and media,, of the new organizational structure of the DWD. Within the international collaboration of the National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHS's) organized by the World Meteorological Organi- zation (WMO), the DWD runs one of the Regional Specialized Meteorological Centres (RSMC's) of the Global Data Processing System (GDPS) of the World Weather Watch (WWW). In this function the DWD has to provide basic weather analyses and forecasts for Europe and the North Atlantic. The backbone of all activities of the DWD in weather forecasting is a chain of Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP)-models providing analyses as well as forecasts up to seven days ahead. In this paper this model chain and its use in operational forecasting is described. TI IF MODEL Cl IAIN The model chain of the DWD consists of three NWP models, namely - a global model (GM), - a limited area model covering Europe and the North Atlantic (called ,Europa- Modell,,, EM), and - a high resolution model covering Germany and the neighbouring countries (called ,Deutschland-Modell,,, DM). IBudl. Soc. (a . Cicnc.], Vol. XV, Mini. 1, 1995 120 (/// 1101) 13 (ILILV'OFFI/F/)EC7:c'C/I//I)V Ill /2/ (IL VII The global model (GM) has been derived from a similar model of the Euro- pean Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting (ECMWF). -

Kunst Im Deutschen Wetterdienst

Kunst im Deutschen Wetterdienst Patrick Raddatz Before And After Science „Aufgabe von Kunst ist es heute, Chaos in die Ordnung zu bringen“ Kunst im Deutschen Wetterdienst Als ich diesen Aphorismus des Philosophen Theodor Adorno (1903 – 1969) neulich in einem populären Kunst - magazin las, kamen mir unwillkürlich die Arbeiten von Patrick Raddatz in den Sinn, die unsere Kunst-Jury gerade für die Ausstellung des Deutschen Wetterdienstes im Rahmen der Offenbacher Kunstansichten 2013 ausgewählt hatte. Ich stellte mir die Frage, ob der in Berlin geborene Künstler mit seinen „Nebelbildern“ Partrick Raddatz eigentlich auch ein Chaos in einer vorgegebenen Ordnung schaffen will. Den von ihm abgelichteten Before And After Science menschenleeren Räumen wird durch künstlichen Nebel quasi der Boden entzogen, die Trittsicherheit geht verloren, das Ungewisse lauert in einer nicht zu fassenden Tiefe. Die vermeintliche Ruhe löst Unbehagen beim Betrachter aus. Chaos? Das Adorno-Zitat geht noch weiter: „Künstlerische Produktivität ist das Vermögen der Willkür im Unwillkürlichen.“ Dieser Satz war mir äußerst willkommen, glaubte ich doch damit Patrick Raddatz durch - schaut zu haben. Habe ich das wirklich oder denkt unser Protagonist viel subtiler? Diese Frage mag ein Ein - stieg in unsere Ausstellung sein, die dem Konzeptkünstler und Fotografen gewidmet ist, der an der Offenbacher Hochschule für Gestaltung studiert hat. Wir sind Patrick Raddatz besonders dankbar, dass er einige Arbeiten in den Räumen unserer Offenbacher Zentrale gefertigt hat, nämlich in unserem TV-Studio und unseren Laboreinrichtungen. Ungewohnte Ansichten! Neue Einsichten? Der Deutsche Wetterdienst versteht sein kulturelles Engagement als gesellschaftlichen Auftrag und selbst - verständlichen Bestandteil seiner Unternehmenskultur. Die Kunstwerke in unserem Haus sollen keine bloßen Dekorationsobjekte sein, sondern unsere Räumlichkeiten zu anregenden Kommunikations- und Begegnungs - stätten machen. -

Book of Abstracts

Book of Abstracts DOI: 10.5676/DWD pub/nwv/iccarus 2021 Max-Planck-Institut für Meteorologie DOI: 10.5676/DWD pub/nwv/iccarus 2021 The CC license “BY-NC-ND” allows others only to download the publication and share it with others as long as they credit the publication, but they can’t change it in any way or use it commercially. Publisher Editors Deutscher Wetterdienst Daniel Rieger, DWD, Business Area “Research and Development” [email protected] Frankfurter Straße 135 Christian Steger, DWD, 63067 Offenbach [email protected] www.dwd.de Contents 1 Invited & Solicited Talks7 Developing the ICON-A model for direct QBO simulations on GPUs...........7 ICON-Land/JSBACH: A Framework for the Land Component in the ICON Modeling System.................................7 Advances in forecast quality achieved with ICON-D2, and upcoming further development steps................................8 Once upon a Time at DWD - The COSMO-Model.....................8 HPC Infrastructure of ICON for high-res simulations....................9 Waves and drag processes in atmospheric models......................9 Status and applications of the modelling system ICON-ART................9 2 Special Session: ICON-Seamless 11 Roadmap to ICON-Seamless................................. 11 The ICON-System at MPI-M and its application for Climate Simula- tions........................................... 11 Sapphire - towards the next generation of Earth System models.............. 11 3 Climate Model Applications 13 Tuning ICON-NWP for Climate applications........................ 13 Impact of Urban Canopy Parameters on a Megacity's Modelled Thermal Environment. 13 COSMO-CLM Performance and Projection of Daily and Hourly Tem- peratures Reaching 50◦C or Higher in Southern Iraq................. 14 COSMO-CLM Russian Arctic hindcast 1980 { 2016: modelling work- flow, evaluation techniques and preliminary assessment...............