Drug Induced Parkinsonism: an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 2. 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially

Table 2. 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults Strength of Organ System/ Recommendat Quality of Recomm Therapeutic Category/Drug(s) Rationale ion Evidence endation References Anticholinergics (excludes TCAs) First-generation antihistamines Highly anticholinergic; Avoid Hydroxyzin Strong Agostini 2001 (as single agent or as part of clearance reduced with e and Boustani 2007 combination products) advanced age, and promethazi Guaiana 2010 Brompheniramine tolerance develops ne: high; Han 2001 Carbinoxamine when used as hypnotic; All others: Rudolph 2008 Chlorpheniramine increased risk of moderate Clemastine confusion, dry mouth, Cyproheptadine constipation, and other Dexbrompheniramine anticholinergic Dexchlorpheniramine effects/toxicity. Diphenhydramine (oral) Doxylamine Use of diphenhydramine in Hydroxyzine special situations such Promethazine as acute treatment of Triprolidine severe allergic reaction may be appropriate. Antiparkinson agents Not recommended for Avoid Moderate Strong Rudolph 2008 Benztropine (oral) prevention of Trihexyphenidyl extrapyramidal symptoms with antipsychotics; more effective agents available for treatment of Parkinson disease. Antispasmodics Highly anticholinergic, Avoid Moderate Strong Lechevallier- Belladonna alkaloids uncertain except in Michel 2005 Clidinium-chlordiazepoxide effectiveness. short-term Rudolph 2008 Dicyclomine palliative Hyoscyamine care to Propantheline decrease Scopolamine oral secretions. Antithrombotics Dipyridamole, oral short-acting* May -

Pharmacologyonline 2: 971-1020 (2009) Newsletter Gabriella Galizia

Pharmacologyonline 2: 971-1020 (2009) Newsletter Gabriella Galizia THE TREATMENT OF THE SCHIZOPHRENIA: AN OVERVIEW Gabriella Galizia School of Pharmacy,University of Salerno, Italy e-mail: [email protected] Summary The schizophrenia is a kind of psychiatric disease, characterized by a course longer than six months (usually chronic or relapsing), by the persistence of symptoms of alteration of mind, behaviour and emotion, with such a seriousness to limitate the normal activity of a person. The terms antipsychotic and neuroleptic define a group of medicine principally used to treat schizophrenia, but they are also efficacious for other psychosis and in states of psychic agitation. The antipsychotics are divided into two classes: classic or typical and atypical. The paliperidone, the major metabolite of risperidone, shares with the native drug the characteristics of receptoral bond and of antagonism of serotonin (5HT2A) and dopamine (D2). It's available in a prolonged release formulation and it allows the administration once daily. Besides, the paliperidone has a pharmacological action independent of CYT P450 and in such way a lot of due pharmacological interactions would be avoided to interference with the activity of the CYP2D6, that is known to have involved in the metabolism of the 25% of the drugs of commune therapeutic employment. Introduction The schizophrenia has been a very hard disease to investigate by the research. This is not surprising because it involves the most mysterious aspects of human mind, as emotions and cognitive processes. According to scientific conventions, the schizophrenia is a kind of psychiatric disease, characterized by a course longer than six months (usually chronic or relapsing), by the persistence of symptoms of alteration of mind, behaviour and emotion, with such a seriousness to limitate the normal activity of a person. -

Management of Major Depressive Disorder Clinical Practice Guidelines May 2014

Federal Bureau of Prisons Management of Major Depressive Disorder Clinical Practice Guidelines May 2014 Table of Contents 1. Purpose ............................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Natural History ................................................................................................................................. 2 Special Considerations ...................................................................................................................... 2 3. Screening ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Screening Questions .......................................................................................................................... 3 Further Screening Methods................................................................................................................ 4 4. Diagnosis ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Depression: Three Levels of Severity ............................................................................................... 4 Clinical Interview and Documentation of Risk Assessment............................................................... -

Tactile Stimulation on Adulthood Modifies the HPA Axis, Neurotrophic Factors, and GFAP Signaling Reverting Depression-Like Behavior in Female Rats

Molecular Neurobiology (2019) 56:6239–6250 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-019-1522-5 Tactile Stimulation on Adulthood Modifies the HPA Axis, Neurotrophic Factors, and GFAP Signaling Reverting Depression-Like Behavior in Female Rats Kr. Roversi1 & Caren Tatiane de David Antoniazzi1 & L. H. Milanesi1 & H. Z. Rosa1 & M. Kronbauer1 & D. R. Rossato2 & T. Duarte1 & M. M. Duarte3 & Marilise E. Burger1 Received: 9 October 2018 /Accepted: 30 January 2019 /Published online: 11 February 2019 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Depression is a common psychiatric disease which pharmacological treatment relieves symptoms, but still far from ideal. Tactile stimulation (TS) has shown beneficial influences in neuropsychiatric disorders, but the mechanism of action is not clear. Here, we evaluated the TS influence when applied on adult female rats previously exposed to a reserpine-induced depression-like animal model. Immediately after reserpine model (1 mg/kg/mL, 1×/day, for 3 days), female Wistar rats were submitted to TS (15 min, 3×/day, for 8 days) or not (unhandled). Imipramine (10 mg/kg/mL) was used as positive control. After behavioral assessments, animals were euthanized to collect plasma and prefrontal cortex (PFC). Behavioral observations in the forced swimming test, splash test, and sucrose preference confirmed the reserpine-induced depression-like behavior, which was reversed by TS. Our findings showed that reserpine increased plasma levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone and corticosterone, decreased brain- derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and tropomyosin receptor kinase B, and increased proBDNF immunoreactivity in the PFC, which were also reversed by TS. Moreover, TS reestablished glial fibrillary acidic protein and glucocorticoid receptor levels, decreased by reserpine in PFC, while glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor was increased by TS per se. -

Determination of Salivary Efavirenz by Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry

G Model CHROMB-17040; No. of Pages 5 ARTICLE IN PRESS Journal of Chromatography B, xxx (2010) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Chromatography B journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/chromb Determination of salivary efavirenz by liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry Anri Theron a, Duncan Cromarty b, Malie Rheeders a, Michelle Viljoen a,∗ a Pharmacology, School of Pharmacy & Unit for Drug Research and Development North-West University, Private Bag X6001, Building G16, Room 113, Potchefstroom 2520, South Africa b Department of Pharmacology, Medical School, University of Pretoria, PO Box 2034, Pretoria 0001, South Africa article info abstract Article history: A novel and robust screening method for the determination of the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase Received 12 May 2010 inhibitor, efavirenz (EFV), in human saliva has been developed and validated based on high perfor- Accepted 31 August 2010 mance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS). Sample preparation of the saliva Available online xxx involved solid-phase extraction (SPE) on C18 cartridges. The analytes were separated by high perfor- mance liquid chromatography (Phenomenex Kinetex C18, 150 mm × 3 mm internal diameter, 2.6 m Keywords: particle size) and detected with tandem mass spectrometry in electrospray positive ionization mode Efavirenz with multiple reaction monitoring. Gradient elution with increasing methanol (MeOH) concentration Saliva LC–MS/MS was used to elute the analytes, at a flow-rate of 0.4 mL/min. The total run time was 8.4 min and the retention times for the internal standard (reserpine) was 5.4 min and for EFV was 6.5 min. -

Gianluca BW.Indd

Use and safety of psychotropic drugs in elderly patients Gianluca Trifi rò GGianlucaianluca BBW.inddW.indd 1 225-May-095-May-09 111:22:461:22:46 AAMM Th e work presented in this thesis was conducted both at the Department of Medical Informatics of the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Th e Netherlands and the Depart- ment of Clinical and Experimental Medicine and Pharmacology of University of Messina, Messina, Italy. Th e studies reported in chapter 2.2 and 4.3 were respectively supported by grants from the Italian Drug Agency and Pfi zer. Th e contributions of the general practitioners participating in the IPCI, Health Search/ Th ales, and Arianna databases are greatly acknowledged. Financial support for printing and distribution of this thesis was kindly provided by IPCI, SIMG/Health Search, Eli Lilly Nederland BV, Boehringer-Ingelheim B.V., Novartis Pharma B.V. and University of Messina. Cover design by Emanuela Punzo, Antonio Franco e Gianluca Trifi rò. Th e background photo in the cover is a landscape from Santa Lucia del Mela (Sicily) and was kindly pro- vided by Franco Trifi rò. Th e photo of the elderly person is from Antonio Franco Trifi rò. Layout and print by Optima Grafi sche Communicatie, Rotterdam, Th e Netherlands. GGianlucaianluca BBW.inddW.indd 2 225-May-095-May-09 111:22:481:22:48 AAMM Use and Safety of Psychotropic Drugs in Elderly Patients Gebruik en veiligheid van psychotropische medicaties in de oudere patienten Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de rector magnifi cus Prof.dr. -

Phase I Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacogenetics Study of the Antituberculosis Drug PA-824 with Concomitant Lopinavir-Ritonavir, Efavirenz, Or Rifampin

Phase I Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacogenetics Study of the Antituberculosis Drug PA-824 with Concomitant Lopinavir-Ritonavir, Efavirenz, or Rifampin Kelly E. Dooley,a Anne F. Luetkemeyer,b Jeong-Gun Park,c Reena Allen,d Yoninah Cramer,c Stephen Murray,e Deborah Sutherland,f Francesca Aweeka,b Susan L. Koletar,g Florence Marzan,b Jing Bao,h Rada Savic,b David W. Haas,f the AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5306 Study Team Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USAa; University of California, San Francisco, California, USAb; Statistical and Data Analysis Center, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USAc; Social & Scientific Systems, Inc., Silver Spring, Maryland, USAd; Global Alliance for TB Drug Development, New York, New York, USAe; Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee, USAf; Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USAg; Henry M. Jackson Foundation, Division of AIDS, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USAh There is an urgent need for new antituberculosis (anti-TB) drugs, including agents that are safe and effective with concomitant antiretrovirals (ARV) and first-line TB drugs. PA-824 is a novel antituberculosis nitroimidazole in late-phase clinical develop- ment. Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A, which can be induced or inhibited by ARV and antituberculosis drugs, is a minor (ϳ20%) metabolic pathway for PA-824. In a phase I clinical trial, we characterized interactions between PA-824 and efavirenz (arm 1), lopinavir/ritonavir (arm 2), and rifampin (arm 3) in healthy, HIV-uninfected volunteers without TB disease. Participants in arms 1 and 2 were randomized to receive drugs via sequence 1 (PA-824 alone, washout, ARV, and ARV plus PA-824) or sequence 2 (ARV, ARV with PA-824, washout, and PA-824 alone). -

Neuromodulators for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (Disorders of Gutlbrain Interaction): a Rome Foundation Working Team Report Douglas A

Gastroenterology 2018;154:1140–1171 SPECIAL REPORT Neuromodulators for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (Disorders of GutLBrain Interaction): A Rome Foundation Working Team Report Douglas A. Drossman,1,2 Jan Tack,3 Alexander C. Ford,4,5 Eva Szigethy,6 Hans Törnblom,7 and Lukas Van Oudenhove8 1Center for Functional Gastrointestinal and Motility Disorders, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina; 2Center for Education and Practice of Biopsychosocial Care and Drossman Gastroenterology, Chapel Hill, North Carolina; 3Translational Research Center for Gastrointestinal Disorders, University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; 4Leeds Institute of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom; 5Leeds Gastroenterology Institute, St James’s University Hospital, Leeds, United Kingdom; 6Departments of Psychiatry and Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; 7Departments of Internal Medicine and Clinical Nutrition, Institute of Medicine, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden; and 8Laboratory for BrainÀGut Axis Studies, Translational Research Center for Gastrointestinal Disorders, University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium BACKGROUND & AIMS: Central neuromodulators (antide- summary information and guidelines for the use of central pressants, antipsychotics, and other central nervous neuromodulators in the treatment of chronic gastrointestinal systemÀtargeted medications) are increasingly used for treat- symptoms and FGIDs. Further studies are needed to confirm ment -

Medications to Be Avoided Or Used with Caution in Parkinson's Disease

Medications To Be Avoided Or Used With Caution in Parkinson’s Disease This medication list is not intended to be complete and additional brand names may be found for each medication. Every patient is different and you may need to take one of these medications despite caution against it. Please discuss your particular situation with your physician and do not stop any medication that you are currently taking without first seeking advice from your physician. Most medications should be tapered off and not stopped suddenly. Although you may not be taking these medications at home, one of these medications may be introduced while hospitalized. If a hospitalization is planned, please have your neurologist contact your treating physician in the hospital to advise which medications should be avoided. Medications to be avoided or used with caution in combination with Selegiline HCL (Eldepryl®, Deprenyl®, Zelapar®), Rasagiline (Azilect®) and Safinamide (Xadago®) Medication Type Medication Name Brand Name Narcotics/Analgesics Meperidine Demerol® Tramadol Ultram® Methadone Dolophine® Propoxyphene Darvon® Antidepressants St. John’s Wort Several Brands Muscle Relaxants Cyclobenzaprine Flexeril® Cough Suppressants Dextromethorphan Robitussin® products, other brands — found as an ingredient in various cough and cold medications Decongestants/Stimulants Pseudoephedrine Sudafed® products, other Phenylephrine brands — found as an ingredient Ephedrine in various cold and allergy medications Other medications Linezolid (antibiotic) Zyvox® that inhibit Monoamine oxidase Phenelzine Nardil® Tranylcypromine Parnate® Isocarboxazid Marplan® Note: Additional medications are cautioned against in people taking Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI), including other opioids (beyond what is mentioned in the chart above), most classes of antidepressants and other stimulants (beyond what is mentioned in the chart above). -

VA/DOD Chronic Multisymptom Illness Clinical Practice Guideline

VA/DoD CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF CHRONIC MULTISYMPTOM ILLNESS Department of Veterans Affairs Department of Defense QUALIFYING STATEMENTS The Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense guidelines are based upon the best information available at the time of publication. They are designed to provide information and assist decision-making. They are not intended to define a standard of care and should not be construed as one. Neither should they be interpreted as prescribing an exclusive course of management. This Clinical Practice Guideline is based on a systematic review of both clinical and epidemiological evidence. Developed by a panel of multidisciplinary experts, it provides a clear explanation of the logical relationships between various care options and health outcomes while rating both the quality of the evidence and the strength of the recommendations. Variations in practice will inevitably and appropriately occur when clinicians take into account the needs of individual patients, available resources, and limitations unique to an institution or type of practice. Every healthcare professional making use of these guidelines is responsible for evaluating the appropriateness of applying them in the setting of any particular clinical situation. These guidelines are not intended to represent TRICARE policy. Further, inclusion of recommendations for specific testing and/or therapeutic interventions within these guidelines does not guarantee coverage of civilian sector care. Additional information on current TRICARE benefits may be found at www.tricare.mil or by contacting your regional TRICARE Managed Care Support Contractor Version 2.0 – 2014 October 2014 Page 1 of 89 Table of Contents Background ................................................................................................................................................... 3 About this Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) ................................................................................................ -

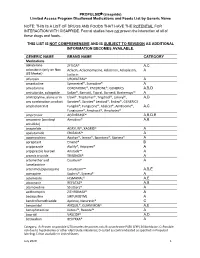

PROPULSID® (Cisapride) Limited Access Program

PROPULSID (cisapride) Limited Access Program Disallowed Medications and Foods List by Generic Name NOTE: THIS IS A LIST OF DRUGS AND FOODS THAT HAVE THE POTENTIAL FOR INTERACTION WITH CISAPRIDE. Formal studies have not proven the interaction of all of these drugs and foods. THIS LIST IS NOT COMPREHENSIVE AND IS SUBJECT TO REVISION AS ADDITIONAL INFORMATION BECOMES AVAILABLE. GENERIC NAME BRAND NAME CATEGORY Medications abiraterone ZYTIGA® A,C aclarubicin (only on Non Aclacin, Aclacinomycine, Aclacinon, Aclaplastin, A US Market) Jaclacin alfuzosin UROXATRAL® A amantadine Symmetrel®, Symadine® A amiodarone CORDARONE®, PACERONE®, GENERICS A,B,D amisulpride, sultopride Solian®, Barnotil, Topral, Barnetil, Barhemsys™ A amitriptyline, alone or in Elavil®, Tryptomer®, Tryptizol®, Laroxyl®, A,D any combination product Saroten®, Sarotex® Lentizol®, Endep®, GENERICS amphotericin B Fungilin®, Fungizone®, Abelcet®, AmBisome®, A,C Fungisome®, Amphocil®, Amphotec® amprenavir AGENERASE® A,B,D,E amsacrine (acridinyl Amsidine® A,B anisidide) anagrelide AGRYLIN®, XAGRID® A apalutamide ERLEADA™ A apomorphine Apokyn®, Ixense®, Spontane®, Uprima® A aprepitant Emend® B aripiprazole Abilify®, Aripiprex® A aripiprazole lauroxil Aristada™ A arsenic trioxide TRISENOX® A artemether and Coartem® A lumefantrine artenimol/piperaquine Eurartesim™ A,B,E asenapine Saphris®, Sycrest® A astemizole HISMANAL® A,E atazanavir REYATAZ® A,B atomoxetine Strattera® A azithromycin ZITHROMAX® A bedaquiline SIRTURO(TM) A bendroflumethiazide Aprinox, Naturetin® C benperidol ANQUIL®, -

Levosulpiride : a Review

DELHI PSYCHIATRY JOURNAL Vol. 10 No.2 OCTOBER 2007 Drug Review Levosulpiride : A Review Sparsh Gupta, Gobind Rai Garg, Sumita Halder, Krishna Kishore Sharma Department of Pharmacology, University College of Medical Sciences & G.T.B. Hospital, Dilshad Garden, Delhi-110095 Dopamine is a neurotransmitter known to be Mechanism of action involved in the regulation of mood and behavior. Levosulpride is an atypical antipsychotic agent Psychotic illness is thought to be caused due to that blocks the presynaptic dopaminergic D 2 disturbance of neurotransmitters (chiefly dopamine) receptors.1 Like its parent compound, levosulpiride in the brain. Schizophrenia is a psychotic illness shows antagonism at D and D receptors present 3 2 characterized by dopamine over activity in the brain presynaptically as well as postsynaptically in the and so anti dopaminergic drugs are a useful rat striatum or nucleus accumbens2. The preferential component of the therapy for the management of binding of the presynaptic dopamine receptors this disease. decreases the synthesis and release of dopamine at Levosulpiride is the levo enantiomer of low doses whereas it causes postsynaptic D 2 sulpiride. It is a substituted benzamide which is receptor antagonism at higher dose. This receptor meant to be used for several indications: depression, profile of the drug along with its limbic selectivity psychosis, somatoform disorders, emesis and explains its effectiveness in the management of both dyspepsia. It is physically present as a white positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia.3 crystalline powder with the chemical structure as follows: Pharmacokinetics The parent drug is given in a dose of 400-1800 mg orally daily although a much lower dose is effective for producing antidepressant effect (about 50-300 mg).The plasma t of the drug is about 6-8 1/2 hours.