VA/DOD Chronic Multisymptom Illness Clinical Practice Guideline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pharmacologyonline 2: 971-1020 (2009) Newsletter Gabriella Galizia

Pharmacologyonline 2: 971-1020 (2009) Newsletter Gabriella Galizia THE TREATMENT OF THE SCHIZOPHRENIA: AN OVERVIEW Gabriella Galizia School of Pharmacy,University of Salerno, Italy e-mail: [email protected] Summary The schizophrenia is a kind of psychiatric disease, characterized by a course longer than six months (usually chronic or relapsing), by the persistence of symptoms of alteration of mind, behaviour and emotion, with such a seriousness to limitate the normal activity of a person. The terms antipsychotic and neuroleptic define a group of medicine principally used to treat schizophrenia, but they are also efficacious for other psychosis and in states of psychic agitation. The antipsychotics are divided into two classes: classic or typical and atypical. The paliperidone, the major metabolite of risperidone, shares with the native drug the characteristics of receptoral bond and of antagonism of serotonin (5HT2A) and dopamine (D2). It's available in a prolonged release formulation and it allows the administration once daily. Besides, the paliperidone has a pharmacological action independent of CYT P450 and in such way a lot of due pharmacological interactions would be avoided to interference with the activity of the CYP2D6, that is known to have involved in the metabolism of the 25% of the drugs of commune therapeutic employment. Introduction The schizophrenia has been a very hard disease to investigate by the research. This is not surprising because it involves the most mysterious aspects of human mind, as emotions and cognitive processes. According to scientific conventions, the schizophrenia is a kind of psychiatric disease, characterized by a course longer than six months (usually chronic or relapsing), by the persistence of symptoms of alteration of mind, behaviour and emotion, with such a seriousness to limitate the normal activity of a person. -

Gianluca BW.Indd

Use and safety of psychotropic drugs in elderly patients Gianluca Trifi rò GGianlucaianluca BBW.inddW.indd 1 225-May-095-May-09 111:22:461:22:46 AAMM Th e work presented in this thesis was conducted both at the Department of Medical Informatics of the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Th e Netherlands and the Depart- ment of Clinical and Experimental Medicine and Pharmacology of University of Messina, Messina, Italy. Th e studies reported in chapter 2.2 and 4.3 were respectively supported by grants from the Italian Drug Agency and Pfi zer. Th e contributions of the general practitioners participating in the IPCI, Health Search/ Th ales, and Arianna databases are greatly acknowledged. Financial support for printing and distribution of this thesis was kindly provided by IPCI, SIMG/Health Search, Eli Lilly Nederland BV, Boehringer-Ingelheim B.V., Novartis Pharma B.V. and University of Messina. Cover design by Emanuela Punzo, Antonio Franco e Gianluca Trifi rò. Th e background photo in the cover is a landscape from Santa Lucia del Mela (Sicily) and was kindly pro- vided by Franco Trifi rò. Th e photo of the elderly person is from Antonio Franco Trifi rò. Layout and print by Optima Grafi sche Communicatie, Rotterdam, Th e Netherlands. GGianlucaianluca BBW.inddW.indd 2 225-May-095-May-09 111:22:481:22:48 AAMM Use and Safety of Psychotropic Drugs in Elderly Patients Gebruik en veiligheid van psychotropische medicaties in de oudere patienten Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de rector magnifi cus Prof.dr. -

Neuromodulators for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (Disorders of Gutlbrain Interaction): a Rome Foundation Working Team Report Douglas A

Gastroenterology 2018;154:1140–1171 SPECIAL REPORT Neuromodulators for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (Disorders of GutLBrain Interaction): A Rome Foundation Working Team Report Douglas A. Drossman,1,2 Jan Tack,3 Alexander C. Ford,4,5 Eva Szigethy,6 Hans Törnblom,7 and Lukas Van Oudenhove8 1Center for Functional Gastrointestinal and Motility Disorders, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina; 2Center for Education and Practice of Biopsychosocial Care and Drossman Gastroenterology, Chapel Hill, North Carolina; 3Translational Research Center for Gastrointestinal Disorders, University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; 4Leeds Institute of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom; 5Leeds Gastroenterology Institute, St James’s University Hospital, Leeds, United Kingdom; 6Departments of Psychiatry and Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; 7Departments of Internal Medicine and Clinical Nutrition, Institute of Medicine, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden; and 8Laboratory for BrainÀGut Axis Studies, Translational Research Center for Gastrointestinal Disorders, University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium BACKGROUND & AIMS: Central neuromodulators (antide- summary information and guidelines for the use of central pressants, antipsychotics, and other central nervous neuromodulators in the treatment of chronic gastrointestinal systemÀtargeted medications) are increasingly used for treat- symptoms and FGIDs. Further studies are needed to confirm ment -

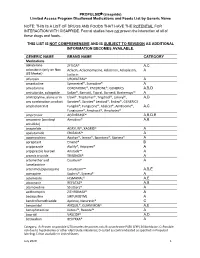

PROPULSID® (Cisapride) Limited Access Program

PROPULSID (cisapride) Limited Access Program Disallowed Medications and Foods List by Generic Name NOTE: THIS IS A LIST OF DRUGS AND FOODS THAT HAVE THE POTENTIAL FOR INTERACTION WITH CISAPRIDE. Formal studies have not proven the interaction of all of these drugs and foods. THIS LIST IS NOT COMPREHENSIVE AND IS SUBJECT TO REVISION AS ADDITIONAL INFORMATION BECOMES AVAILABLE. GENERIC NAME BRAND NAME CATEGORY Medications abiraterone ZYTIGA® A,C aclarubicin (only on Non Aclacin, Aclacinomycine, Aclacinon, Aclaplastin, A US Market) Jaclacin alfuzosin UROXATRAL® A amantadine Symmetrel®, Symadine® A amiodarone CORDARONE®, PACERONE®, GENERICS A,B,D amisulpride, sultopride Solian®, Barnotil, Topral, Barnetil, Barhemsys™ A amitriptyline, alone or in Elavil®, Tryptomer®, Tryptizol®, Laroxyl®, A,D any combination product Saroten®, Sarotex® Lentizol®, Endep®, GENERICS amphotericin B Fungilin®, Fungizone®, Abelcet®, AmBisome®, A,C Fungisome®, Amphocil®, Amphotec® amprenavir AGENERASE® A,B,D,E amsacrine (acridinyl Amsidine® A,B anisidide) anagrelide AGRYLIN®, XAGRID® A apalutamide ERLEADA™ A apomorphine Apokyn®, Ixense®, Spontane®, Uprima® A aprepitant Emend® B aripiprazole Abilify®, Aripiprex® A aripiprazole lauroxil Aristada™ A arsenic trioxide TRISENOX® A artemether and Coartem® A lumefantrine artenimol/piperaquine Eurartesim™ A,B,E asenapine Saphris®, Sycrest® A astemizole HISMANAL® A,E atazanavir REYATAZ® A,B atomoxetine Strattera® A azithromycin ZITHROMAX® A bedaquiline SIRTURO(TM) A bendroflumethiazide Aprinox, Naturetin® C benperidol ANQUIL®, -

Levosulpiride : a Review

DELHI PSYCHIATRY JOURNAL Vol. 10 No.2 OCTOBER 2007 Drug Review Levosulpiride : A Review Sparsh Gupta, Gobind Rai Garg, Sumita Halder, Krishna Kishore Sharma Department of Pharmacology, University College of Medical Sciences & G.T.B. Hospital, Dilshad Garden, Delhi-110095 Dopamine is a neurotransmitter known to be Mechanism of action involved in the regulation of mood and behavior. Levosulpride is an atypical antipsychotic agent Psychotic illness is thought to be caused due to that blocks the presynaptic dopaminergic D 2 disturbance of neurotransmitters (chiefly dopamine) receptors.1 Like its parent compound, levosulpiride in the brain. Schizophrenia is a psychotic illness shows antagonism at D and D receptors present 3 2 characterized by dopamine over activity in the brain presynaptically as well as postsynaptically in the and so anti dopaminergic drugs are a useful rat striatum or nucleus accumbens2. The preferential component of the therapy for the management of binding of the presynaptic dopamine receptors this disease. decreases the synthesis and release of dopamine at Levosulpiride is the levo enantiomer of low doses whereas it causes postsynaptic D 2 sulpiride. It is a substituted benzamide which is receptor antagonism at higher dose. This receptor meant to be used for several indications: depression, profile of the drug along with its limbic selectivity psychosis, somatoform disorders, emesis and explains its effectiveness in the management of both dyspepsia. It is physically present as a white positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia.3 crystalline powder with the chemical structure as follows: Pharmacokinetics The parent drug is given in a dose of 400-1800 mg orally daily although a much lower dose is effective for producing antidepressant effect (about 50-300 mg).The plasma t of the drug is about 6-8 1/2 hours. -

Effect of Antidepressants and Psychological Therapies in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: an Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

This is a repository copy of Effect of Antidepressants and Psychological Therapies in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/135430/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Ford, AC orcid.org/0000-0001-6371-4359, Lacy, BE, Harris, LA et al. (2 more authors) (2019) Effect of Antidepressants and Psychological Therapies in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. The American journal of gastroenterology, 114 (1). pp. 21-39. ISSN 0002-9270 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41395-018-0222-5 © 2018 The American College of Gastroenterology. This is an author produced version of a paper published in The American journal of gastroenterology. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Ford et al. 1 of 66 Accepted for publication 29th June 2018 TITLE PAGE Title: Effect of Antidepressants and Psychological Therapies in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. -

Electronic Search Strategies

Appendix 1: electronic search strategies The following search strategy will be applied in PubMed: ("Antipsychotic Agents"[Mesh] OR acepromazine OR acetophenazine OR amisulpride OR aripiprazole OR asenapine OR benperidol OR bromperidol OR butaperazine OR Chlorpromazine OR chlorproethazine OR chlorprothixene OR clopenthixol OR clotiapine OR clozapine OR cyamemazine OR dixyrazine OR droperidol OR fluanisone OR flupentixol OR fluphenazine OR fluspirilene OR haloperidol OR iloperidone OR levomepromazine OR levosulpiride OR loxapine OR lurasidone OR melperone OR mesoridazine OR molindone OR moperone OR mosapramine OR olanzapine OR oxypertine OR paliperidone OR penfluridol OR perazine OR periciazine OR perphenazine OR pimozide OR pipamperone OR pipotiazine OR prochlorperazine OR promazine OR prothipendyl OR quetiapine OR remoxipride OR risperidone OR sertindole OR sulpiride OR sultopride OR tiapride OR thiopropazate OR thioproperazine OR thioridazine OR tiotixene OR trifluoperazine OR trifluperidol OR triflupromazine OR veralipride OR ziprasidone OR zotepine OR zuclopenthixol ) AND ("Randomized Controlled Trial"[ptyp] OR "Controlled Clinical Trial"[ptyp] OR "Multicenter Study"[ptyp] OR "randomized"[tiab] OR "randomised"[tiab] OR "placebo"[tiab] OR "randomly"[tiab] OR "trial"[tiab] OR controlled[ti] OR randomized controlled trials[mh] OR random allocation[mh] OR double-blind method[mh] OR single-blind method[mh] OR "Clinical Trial"[Ptyp] OR "Clinical Trials as Topic"[Mesh]) AND (((Schizo*[tiab] OR Psychosis[tiab] OR psychoses[tiab] OR psychotic[tiab] OR disturbed[tiab] OR paranoid[tiab] OR paranoia[tiab]) AND ((Child*[ti] OR Paediatric[ti] OR Pediatric[ti] OR Juvenile[ti] OR Youth[ti] OR Young[ti] OR Adolesc*[ti] OR Teenage*[ti] OR early*[ti] OR kids[ti] OR infant*[ti] OR toddler*[ti] OR boys[ti] OR girls[ti] OR "Child"[Mesh]) OR "Infant"[Mesh])) OR ("Schizophrenia, Childhood"[Mesh])). -

Tardive Akathisia

HEALTH & SAFETY: PSYCHIATRIC MEDICATIONS Tardive Akathisia FACT SHEET Tardive Akathisia BQIS Fact Sheets provide a general overview on topics important to supporting an individual’s health and safety and to improving their quality of life. This document provides general information on the topic and is not intended to replace team assessment, decision-making, or medical advice. This is the ninth of ten Fact Sheets regarding psychotropic medications. Intended Outcomes Individuals will understand the symptoms, common causes, and treatment of tardive akathisia. Definitions Akathisia: A movement disorder characterized by motor restlessness/a feeling of inner restlessness with a compelling need to be moving. Tardive akathisia: A severe prolonged form of akathisia which may persist after stopping the medica- tion causing the symptoms. Facts • Akathisia is: – the most common drug induced movement disorder. – a side effect of medication. – most often caused by antipsychotic medications that block dopamine. • Medications with akathisia as a potential side effect include: – Benzisothiazole (ziprasidone) – Benzisoxazole (iloperidone) – Butyrophenones (haloperidol, droperidol) – Calcium channel blockers (flunarizine, cinnarizine) – Dibenzazepine (loxapine, asenapine) – Dibenzodiazepine (clozapine, quetiapine) – Diphenylbutylpiperidine (pimozide) – Indolones (molindone) – Lithium – Phenothiazines (chlorpromazine, triflupromazine, thioridazine, mesoridazine, trifluoperazine, prochlorperazine, perphenazine, fluphenazine, perazine) Bureau of Quality Improvement -

Role of Levosulpiride in the Management of Functional Dyspepsia

Open Access Journal of Family Medicine Research Article Role of Levosulpiride in the Management of Functional Dyspepsia Ratnani IJ*, Panchal BN, Gandhi RR, Vala AU and Mandal K Abstract Department of Psychiary, Government Medical College Functional dyspepsia (FD) consist of variable combination of symptoms and Sir Takhtasinhji General Hospital, Bhavnagar, of gastrointestinal tract like abdominal pain, postprandial fullness, abdominal Gujarat, India bloating, early satiety, nausea, vomiting, heartburn and acid regurgitation, *Corresponding author: Ratnani IJ, Department without any definitive structural or biochemical cause for it. There are varieties of of Psychiary, Government Medical College and Sir treatment options available for management of dyspeptic symptoms including, Takhtasinhji General Hospital, India, Tel: 09925056695; replacement of Non Steroidal Anti Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) with COX- Fax: 91-278-2422011; Email: [email protected] 2 inhibitor, empirical treatment with Proton Pump Inhibitor and treatment of H.pylori infection. Refractory dyspeptic cases, who fail to respond conventional Received: June 22, 2015; Accepted: July 09, 2015; treatment of dyspepsia can be managed with antidepressant or pro kinetic Published: July 10, 2015 drugs. Levosulpiride is an atypical antipsychotic, acts by blocking the presynaptic D2 dopaminergic receptor in the dopaminergic pathway. It was found that levosulpiride have more efficacy in management of dyspeptic symptoms in comparison to antisecretary agents (cimetidine, ranitidine) and prokinetic agents (metaclopramide, domperidone). Levosulpiride is as effective as cisapride in management of dyspepsia, having better tolerability, and relatively milder adverse events. Levosulpiride improves the dyspeptic symptoms like pain, discomfort, fullness, bloating of abdomen, early satiety, nausea, vomiting, associated anxiety symptoms, and health related quality of life impaired by dyspeptic symptoms. -

Genetic and Molecular Aspects of Drug-Induced QT Interval Prolongation

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Genetic and Molecular Aspects of Drug-Induced QT Interval Prolongation Daniela Baracaldo-Santamaría 1 , Kevin Llinás-Caballero 2,3 , Julián Miguel Corso-Ramirez 1 , Carlos Martín Restrepo 2 , Camilo Alberto Dominguez-Dominguez 1 , Dora Janeth Fonseca-Mendoza 2 and Carlos Alberto Calderon-Ospina 2,* 1 School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá 111221, Colombia; [email protected] (D.B.-S.); [email protected] (J.M.C.-R.); [email protected] (C.A.D.-D.) 2 GENIUROS Research Group, Center for Research in Genetics and Genomics (CIGGUR), School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá 111221, Colombia; [email protected] (K.L.-C.); [email protected] (C.M.R.); [email protected] (D.J.F.-M.) 3 Institute for Immunological Research, University of Cartagena, Cartagena 130014, Colombia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +57-1-2970200 (ext. 3318) Abstract: Long QT syndromes can be either acquired or congenital. Drugs are one of the many etiologies that may induce acquired long QT syndrome. In fact, many drugs frequently used in the clinical setting are a known risk factor for a prolonged QT interval, thus increasing the chances of developing torsade de pointes. The molecular mechanisms involved in the prolongation of the QT interval are common to most medications. However, there is considerable inter-individual variability Citation: Baracaldo-Santamaría, D.; Llinás-Caballero, K.; Corso-Ramirez, in drug response, thus making the application of personalized medicine a relevant aspect in long QT J.M.; Restrepo, C.M.; syndrome, in order to evaluate the risk of every individual from a pharmacogenetic standpoint. -

Common Study Protocol for Observational Database Studies WP5 – Analytic Database Studies

Arrhythmogenic potential of drugs FP7-HEALTH-241679 http://www.aritmo-project.org/ Common Study Protocol for Observational Database Studies WP5 – Analytic Database Studies V 1.3 Draft Lead beneficiary: EMC Date: 03/01/2010 Nature: Report Dissemination level: D5.2 Report on Common Study Protocol for Observational Database Studies WP5: Conduct of Additional Observational Security: Studies. Author(s): Gianluca Trifiro’ (EMC), Giampiero Version: v1.1– 2/85 Mazzaglia (F-SIMG) Draft TABLE OF CONTENTS DOCUMENT INFOOMATION AND HISTORY ...........................................................................4 DEFINITIONS .................................................... ERRORE. IL SEGNALIBRO NON È DEFINITO. ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................................6 1. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................7 2. STUDY OBJECTIVES................................ ERRORE. IL SEGNALIBRO NON È DEFINITO. 3. METHODS ..........................................................................................................................8 3.1.STUDY DESIGN ....................................................................................................................8 3.2.DATA SOURCES ..................................................................................................................9 3.2.1. IPCI Database .....................................................................................................9 -

Drug-Induced Parkinsonism

REVIEW Print ISSN 1738-6586 / On-line ISSN 2005-5013 J Clin Neurol 2012;8:15-21 http://dx.doi.org/10.3988/jcn.2012.8.1.15 Open Access Drug-Induced Parkinsonism Hae-Won Shin,a Sun Ju Chungb aDepartment of Neurology, Chung-Ang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea bParkinson/Alzheimer Center, Department of Neurology, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Drug-induced parkinsonism (DIP) is the second-most-common etiology of parkinsonism in the el- derly after Parkinson’s disease (PD). Many patients with DIP may be misdiagnosed with PD be- cause the clinical features of these two conditions are indistinguishable. Moreover, neurological deficits in patients with DIP may be severe enough to affect daily activities and may persist for long periods of time after the cessation of drug taking. In addition to typical antipsychotics, DIP may be caused by gastrointestinal prokinetics, calcium channel blockers, atypical antipsychotics, and anti- epileptic drugs. The clinical manifestations of DIP are classically described as bilateral and sym- metric parkinsonism without tremor at rest. However, about half of DIP patients show asymmetri- Received April 8, 2011 cal parkinsonism and tremor at rest, making it difficult to differentiate DIP from PD. The pathophy- Revised June 28, 2011 siology of DIP is related to drug-induced changes in the basal ganglia motor circuit secondary to Accepted June 28, 2011 dopaminergic receptor blockade. Since these effects are limited to postsynaptic dopaminergic re- Correspondence ceptors, it is expected that presynaptic dopaminergic neurons in the striatum will be intact. Dopa- Sun Ju Chung, MD, PhD mine transporter (DAT) imaging is useful for diagnosing presynaptic parkinsonism.