Andorra's Autonomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalan Farmhouses and Farming Families in Catalonia Between the 16Th and Early 20Th Centuries

CATALAN HISTORICAL REVIEW, 9: 71-84 (2016) Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Barcelona DOI: 10.2436/20.1000.01.122 · ISSN: 2013-407X http://revistes.iec.cat/chr/ Catalan farmhouses and farming families in Catalonia between the 16th and early 20th centuries Assumpta Serra* Institució Catalana d’Estudis Agraris Received 20 May 2015 · Accepted 15 July 2015 Abstract The masia (translated here as the Catalan farmhouse), or the building where people reside on a farming estate, is the outcome of the landscape where it is located. It underwent major changes from its origins in the 11th century until the 16th century, when its evolu- tion peaked and a prototype was reached for Catalonia as a whole. For this reason, in the subsequent centuries the model did not change, but building elements were added to it in order to adapt the home to the times. Catalan farmhouses are a historical testimony, and their changes and enlargements always reflect the needs of their inhabitants and the technological possibilities of the period. Keywords: evolution, architectural models, farmhouses, rural economy, farming families Introduction techniques or the spread of these techniques became availa- ble to more and more people. Larger or more numerous Some years ago, historians stopped studying only the ma- rooms characterised the evolution of a structure that was jor political events or personalities to instead focus on as- originally called a hospici, domus, casa or alberg, although pects that were closer to the majority of the people, because we are not certain of the reason behind such a variety of this is where the interest lies: in learning about our ances- words. -

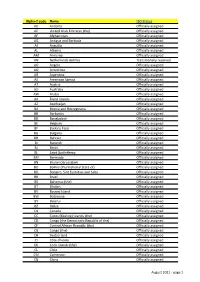

RA List of ISIN Prefixes August 2021

Alpha-2 code Name ISO Status AD Andorra Officially assigned AE United Arab Emirates (the) Officially assigned AF Afghanistan Officially assigned AG Antigua and Barbuda Officially assigned AI Anguilla Officially assigned AL Albania Officially assigned AM Armenia Officially assigned AN Netherlands Antilles Transitionally reserved AO Angola Officially assigned AQ Antarctica Officially assigned AR Argentina Officially assigned AS American Samoa Officially assigned AT Austria Officially assigned AU Australia Officially assigned AW Aruba Officially assigned AX Åland Islands Officially assigned AZ Azerbaijan Officially assigned BA Bosnia and Herzegovina Officially assigned BB Barbados Officially assigned BD Bangladesh Officially assigned BE Belgium Officially assigned BF Burkina Faso Officially assigned BG Bulgaria Officially assigned BH Bahrain Officially assigned BI Burundi Officially assigned BJ Benin Officially assigned BL Saint Barthélemy Officially assigned BM Bermuda Officially assigned BN Brunei Darussalam Officially assigned BO Bolivia (Plurinational State of) Officially assigned BQ Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba Officially assigned BR Brazil Officially assigned BS Bahamas (the) Officially assigned BT Bhutan Officially assigned BV Bouvet Island Officially assigned BW Botswana Officially assigned BY Belarus Officially assigned BZ Belize Officially assigned CA Canada Officially assigned CC Cocos (Keeling) Islands (the) Officially assigned CD Congo (the Democratic Republic of the) Officially assigned CF Central African Republic (the) -

Fuerzas Hidroeléctricas Del Segre, the Gomis Family, Which Founded and Owned the Company, Had Been Involved in the Electricity Business for a Long Time

SHORT ARTICLEST he Image Lourdes Martínez Collection: Fuerzas Prado PHOTOGRAPHY Hidroeléctricas Spain del Segre The cataloguing and simultaneous digitisation should be made of the pictures of workers at of images generated by the Fuerzas Hidro- great heights on the dam wall, transmission eléctricas del Segre company is a project car- towers or bridges), to the difficulties posed by ried out in the National Archive of Catalonia the weather. In this regard, the collection in collaboration with the Fundación Endesa, includes some photographs of the minor resulting in the collection becoming easy to flooding events of the river in March 1947, consult not only in the actual Archive, but also December 1949, May 1950, and May 1956 through the Internet. This was a long-che- (two or three photos per weather phenome- rished ambition of the ANC, since the Fuerzas non), and also of the winds in the winter of Hidroeléctricas del Segre is one of the most 1949-1950. The great flood of June 1953 of comprehensive collections in terms of being the river Segre is particularly well documented, able to monitor the construction of a hydro- with 63 photographs, which convincingly con- electric complex. I am referring, more spe- vey how the river severely punished the area in cifically, to the hydroelectric station of Oliana1 . general and more particularly building work on Indeed, of the 2,723 units catalogued in the the dam. collection, approximately 1,500 pertain to the aforementioned project. These pictures also allow us to study the engi- neering techniques and tools used in the 1940s The construction of the Oliana dam was un- and 1950s, particularly the machinery used, dertaken in 1946. -

Andorra's Constitution of 1993

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:54 constituteproject.org Andorra's Constitution of 1993 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:54 Table of contents Preamble . 5 TITLE I: SOVEREIGNTY OF ANDORRA . 5 Article 1 . 5 Article 2 . 5 Article 3 . 5 TITLE II: RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS . 6 Chapter I: General principles . 6 Chapter II: Andorran nationality . 6 Chapter III: The fundamental rights of the person and public freedoms . 6 Chapter IV: Political rights of Andorran nationals . 9 Chapter V: Rights, and economic, social and cultural principles. 9 Chapter VI: Duties of Andorran nationals and of aliens . 11 Chapter VII: Guarantees of rights and freedoms . 11 TITLE III: THE COPRINCES . 12 Article 43 . 12 Article 44 . 12 Article 45 . 12 Article 46 . 13 Article 47 . 14 Article 48 . 14 Article 49 . 14 TITLE IV: THE GENERAL COUNCIL . 14 Article 50 . 14 Chapter I: Organization of the General Council . 14 Chapter II: Legislative procedure . 16 Chapter III: International treaties . 17 Chapter IV: Relations of the General Council with the Government . 18 TITLE V: THE GOVERNMENT . 19 Article 72 . 19 Article 73 . 19 Article 74 . 20 Article 75 . 20 Article 76 . 20 Article 77 . 20 Article 78 . 20 TITLE VI: TERRITORIAL STRUCTURE . 20 Andorra 1993 Page 2 constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:54 Article 79 . 20 Article 80 . 20 Article 81 . 21 Article 82 . 21 Article 83 . 22 Article 84 . 22 TITLE VII: JUSTICE . 22 Article 85 . -

Report Card: Andorra

Report card Andorra Contents Page Obesity prevalence 2 Overweight/obesity by age 3 Insufficient physical activity 4 Estimated per capita fruit intake 7 Estimated per-capita processed meat intake 8 Estimated per capita whole grains intake 9 Raised blood pressure 10 Raised cholesterol 13 Raised fasting blood glucose 16 Diabetes prevalence 18 1 Obesity prevalence Adults, 2017-2018 Obesity Overweight 50 40 30 % 20 10 0 Adults Men Women Survey type: Measured Age: 18-75 Sample size: 850 Area covered: National References: 2a ENQUESTA NUTRICIONAL D’ANDORRA (ENA 2017-2018). Government of Andorra. Available at https://www.govern.ad/salut/item/download/856_fffdd95ca999812abc80e030626d6f7d (last accessed 09.09.20) Unless otherwise noted, overweight refers to a BMI between 25kg and 29.9kg/m², obesity refers to a BMI greater than 30kg/m². 2 Overweight/obesity by age Adults, 2017-2018 Obesity Overweight 70 60 50 40 % 30 20 10 0 Men Women Men Women Men Women Men Women Age 18-24 Age 25-44 Age 45-64 Age 65-74 Age 65-75 Survey type: Measured Sample size: 850 Area covered: National References: 2a ENQUESTA NUTRICIONAL D’ANDORRA (ENA 2017-2018). Government of Andorra. Available at https://www.govern.ad/salut/item/download/856_fffdd95ca999812abc80e030626d6f7d (last accessed 09.09.20) Unless otherwise noted, overweight refers to a BMI between 25kg and 29.9kg/m², obesity refers to a BMI greater than 30kg/m². 3 Cyprus Portugal Germany Malta Italy (18)30357-7 Serbia 109X Bulgaria Hungary Andorra Greece United Kingdom http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2214- Belgium Romania Slovakia Ireland Poland Slovenia Estonia Norway Czech Republic Croatia Turkey Austria 4 Latvia France Denmark Luxembourg Kazakhstan Netherlands Spain Lithuania Bosnia & Herzegovina Switzerland Sweden Armenia Ukraine Uzbekistan analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. -

CONTRAT De RIVIERE Du SEGRE En CERDAGNE

COMMUNAUTE DE COMMUNES « PYRENEES - CERDAGNE » CONTRAT de RIVIERE du SEGRE en CERDAGNE Dossier définitif Projet cofinancé par l'Union Européenne. Fonds InterReg IIIA Mai 2007 COMMUNAUTE DE COMMUNES « PYRENEES - CERDAGNE » CONTRAT de RIVIERE du SEGRE en CERDAGNE Dossier définitif Projet cofinancé par l'Union Européenne. Fonds InterReg IIIA S.I.E.E. Mai 2007 Société d'Ingénierie pour l'Eau et l'Environnement COMMUNAUTE DE COMMUNES « PYRENEES - CERDAGNE » SOMMAIRE PARTIE A – SYNTHESE DE L’ETAT DES LIEUX ET DU DIAGNOSTIC I. PRESENTATION DU TERRITOIRE ET DES ACTEURS ......................................... 7 I.1. DONNEES DE CADRAGE ................................................................................................. 7 I.2. PERIMETRE DU CONTRAT DE RIVIERE ET ACTEURS......................................................... 8 I.2.1. Le périmètre......................................................................................................... 8 I.2.2. Dynamique du contrat et acteurs......................................................................... 9 I.3. COOPERATION TRANSFRONTALIERE ............................................................................ 12 II. RESSOURCES EN EAU ............................................................................................ 14 II.1. RESSOURCES EN EAU ET PRESSIONS............................................................................. 14 II.1.1. Eaux superficielles............................................................................................. 14 II.1.2. -

Simulating Long-Term Past Changes in the Balance Between Water Demand

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., 11, 12315–12364, 2014 www.hydrol-earth-syst-sci-discuss.net/11/12315/2014/ doi:10.5194/hessd-11-12315-2014 © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Hydrology and Earth System Sciences (HESS). Please refer to the corresponding final paper in HESS if available. Simulating long-term past changes in the balance between water demand and availability and assessing their main drivers at the river basin management scale J. Fabre1, D. Ruelland1, A. Dezetter2, and B. Grouillet1 1CNRS, HydroSciences Laboratory, Place Eugene Bataillon, 34095 Montpellier, France 2IRD, HydroSciences Laboratory, Place Eugene Bataillon, 34095 Montpellier, France Received: 30 September 2014 – Accepted: 15 October 2014 – Published: 4 November 2014 Correspondence to: J. Fabre ([email protected]) Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. 12315 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract The aim of this study was to assess the balance between water demand and availabil- ity and its spatial and temporal variability from 1971 to 2009 in the Herault (2500 km2, France) and the Ebro (85 000 km2, Spain) catchments. Natural streamflow was evalu- 5 ated using a conceptual hydrological model. The regulation of river flow was accounted for through a widely applicable demand-driven reservoir management model applied to the largest dam in the Herault basin and to 11 major dams in the Ebro basin. Urban wa- ter demand was estimated from population and monthly unit water consumption data. -

2019 Pyrenees Cup

1st NEWSLETTER 2019 PYRENEES CUP 1st & 2nd June Parc Olímpic de Segre st 1 June ECA Cup nd 2 June ICF Ranking 1st Newsletter 2019 Canoe Wildwater Pyrenees Cup Contents st 1 NEWSLETTER TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Invitation to 2019 Canoe Slalom Pyrenees Cup 3 Provisional Competition Program 4 Pyrenees Cup rules: entries, participation fee, etc.. 5 Organizing Committee 6 Parc Olímpic del Segre venue 7 How to get to La Seu d’Urgell 8 Contacts 9 Thanks to Institutions and Sponsors 10 1st Newsletter 2019 Canoe Wildwater Pyrenees Cup Invitation to 2019 Canoe Slalom Pyrenees Cup Dear President, Dear Secretary General, The Organizing Committee of the 1st Pyrenees Wildwater Cup cordially invites you to attend the canoe wildwater competitions that are going to be hold in June of 2019. The competition races are sport orientated, to be useful for wildwater training and improvement of technical performance prior to the World Championships that the city is going to host in late September. The individual inscription gives wider opportunities to participate and combine sport schedule. The Pyrenees Cup Organizing Committee welcomes you to join our 2019 events. 1st Newsletter 2019 Canoe Wildwater Pyrenees Cup Provisional program tnd Wednesday, May 22 Nominal entries deadline (through SDP) Tuesday, May 8h – 10h Free training 28th 18h30 – 20h30 Wednesday, May 8h – 10h Free training 29th 18h30 – 20h30 Thursday, May 8h30 – 10h30 Free training th 18h – 20h Free training 30 16h – 18h30 Entries confirmation & participation fee payment 8h30 – 10h30 Free training 17h -

An Analysis of Five European Microstates

Geoforum, Vol. 6, pp. 187-204, 1975. Pergamon Press Ltd. Printed in Great Britain The Plight of the Lilliputians: an Analysis of Five European Microstates Honor6 M. CATUDAL, Jr., Collegeville, Minn.” Summary: The mini- or microstate is an important but little studied phenomenon in political geography. This article seeks to redress the balance and give these entities some of the attention they deserve. In general, five microstates are examined; all are located in Western Europe-Andorra, Liechtenstein, Monaco, San Marino and the Vatican. The degree to which each is autonomous in its internal affairs is thoroughly explored. And the extent to which each has control over its external relations is investigated. Disadvantages stemming from its small size strike at the heart of the ministate problem. And they have forced these nations to adopt practices which should be of use to large states. Zusammenfassung: Dem Zwergstaat hat die politische Geographie wenig Beachtung geschenkt. Urn diese Liicke zu verengen, werden hier fiinf Zwergstaaten im westlichen Europa untersucht: Andorra, Liechtenstein, Monaco, San Marino und der Vatikan. Das Ma13der inneren und lul3eren Autonomie wird griindlich untersucht. Die Kleinheit hat die Zwargstaaten zu Anpassungsformen gezwungen, die such fiir groRe Staaten van Bedeutung sein k8nnten. R&sum& Les Etats nains n’ont g&e fait I’objet d’Btudes de geographic politique. Afin de combler cette lacune, cinq mini-Etats sent examines ici; il s’agit de I’Andorre, du Liechtenstein, de Monaco, de Saint-Marin et du Vatican. Dans quelle mesure ces Etats disposent-ils de l’autonomie interne at ont-ils le contrble de leurs relations extirieures. -

Flash Reports on Labour Law November 2019 Summary and Country Reports

Flash Reports on Labour Law November 2019 Summary and country reports Written by The European Centre of Expertise (ECE), based on reports submitted by the Network of Labour Law Experts November 2019 EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate DG Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion Unit B.2 – Working Conditions Contact: Marie LAGUARRIGUE E-mail: [email protected] European Commission B-1049 Brussels Flash Report 11/2019 Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). LEGAL NOTICE The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s). The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the position or opinion of the European Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person/organisation acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use that might be made of any information contained in this publication. This publication has received financial support from the European Union Programme for Employment and Social Innovation "EaSI" (2014-2020). For further information please consult: http://ec.europa.eu/social/easi. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://www.europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2019 ISBN ABC 12345678 DOI 987654321 © European Union, 2019 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. -

Laws for Legal Immigration in the 27 EU Member States

Laws for Legal Immigration in the 27 EU Member States N° 16 International Migration Law Laws for Legal Immigration in the 27 EU Member States 1 While IOM endeavours to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the content of this paper, the views, findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and field researchers and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the IOM and their Member States. IOM does not accept any liability for any loss which may arise from the reliance on information contained in this paper. Publishers: International Organization for Migration 17 route des Morillons 1211 Geneva 19 Switzerland Tel: +41.22.717 91 11 Fax: +41.22.798 61 50 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.iom.int ISSN 1813-2278 © 2009 International Organization for Migration (IOM) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. 17_09 N° 16 International Migration Law Comparative Study of the Laws in the 27 EU Member States for Legal Immigration Including an Assessment of the Conditions and Formalities Imposed by Each Member State For Newcomers Laws for Legal Immigration in the 27 EU Member States List of Contributors Christine Adam, International Migration Law and Legal Affairs Department, IOM Alexandre Devillard, International Migration Law and Legal Affairs Department, IOM Field Researchers Austria Gerhard Muzak Professor, Vienna University, Institute of Constitutional and Administrative Law, Austria Belgium Philippe De Bruycker Professor, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Institute for European Studies, Belgium Bulgaria Angelina Tchorbadjiyska Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Institute for European Law, Belgium Cyprus Olga Georgiades Lawyer, Lellos P. -

Joint Statement by Albania, Andorra, Australia, Austria

JOINT STATEMENT BY ALBANIA, ANDORRA, AUSTRALIA, AUSTRIA, BELGIUM, BULGARIA, CANADA, COLOMBIA, COOK ISLANDS, CROATIA, CYPRUS, CZECH REPUBLIC, DENMARK, ECUADOR, ESTONIA, FIJI, FINLAND, FRANCE, GEORGIA, GERMANY, GREECE, HONDURAS, HUNGARY, ICELAND, IRELAND, ITALY, JAPAN, LATVIA, LIBERIA, LIECHTENSTEIN, LITHUANIA, LUXEMBOURG, MALTA, MARSHALL ISLANDS, MONTENEGRO, NAURU, NETHERLANDS, NEW ZEALAND, NORWAY, PAPUA NEW GUINEA, PALAU, PERU, POLAND, PORTUGAL, PRINCIPALITY OF MONACO, REPUBLIC OF KOREA, REPUBLIC OF NORTH MACEDONIA, ROMANIA, SAN MARINO, SLOVAKIA, SLOVENIA, SPAIN, SWEDEN, SWITZERLAND, TURKEY, UKRAINE, UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, AND VANUATU AT THE TWENTY-FIFTH SESSION OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE STATES PARTIES 1. We, as States Parties of the Chemical Weapons Convention, condemn in the strongest possible terms the use of a toxic chemical as a weapon in the Russian Federation against Alexei Navalny on 20 August 2020. 2. We welcome the assistance provided by the OPCW Technical Secretariat in the aftermath of Mr. Navalny’s poisoning. OPCW analysis of biomedical samples confirmed the presence of a cholinesterase inhibitor. We note that the cholinesterase inhibitor has been further identified as a nerve agent from a group of chemicals known as “Novichoks”. We have full confidence in the OPCW’s independent expert finding that Mr. Navalny was exposed to a Novichok nerve agent. We note with concern that a Novichok nerve agent was also used in an attack in the United Kingdom in 2018. These agents serve no other purpose than to be used as a chemical weapon. 3. Any poisoning of an individual with a nerve agent is considered a use of a chemical weapon.