Tanit Plana PUBER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sufjan Stevens Yarn/Wire

BAM 2015 Winter/Spring Season #Sufjan Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer Round-Up Sufjan Stevens Yarn/Wire BAM Harvey Theater Jan 20—25 at 7:30pm Running time: one hour and 15 minutes, no intermission Season Sponsor: Viacom is the BAM 2015 Music Sponsor The Steinberg Screen at the BAM Harvey Theater is made possible by The Joseph S. and Diane H. Steinberg Charitable Trust Major support for Round-Up provided by The Frederick Loewe Foundation Major support for music at BAM provided by: Frances Bermanzohn & Alan Roseman Pablo J. Salame Round-Up FILM Director, Composer Sufjan Stevens Cinematographer Aaron Craig Cinematographer Alex Craig Co-Producer Lisa Moran Co-Producer We Are Films COMPANY Sound Mix Dan Bora Lighting Seth Reiser Stage Manager Mary-Sue Gregson Production Management Lisa Moran Live Projection & Design Josh Higgason Round-Up was filmed at the Pendleton Round-Up in eastern Oregon, September, 2013. Additional footage was shot in Brooklyn and upstate New York, July 2014. Courtesy We Are Films Courtesy We Are Films Who’s Who SUFJAN STEVENS was born in Detroit and WE ARE FILMS raised in northern Michigan. He attended Hope Alex and Aaron Craig discovered their passion for College in Holland, MI, and the masters program filmmaking in their early teens. With camcord- for writers at the New School for Social Research ers in hand, willing neighbors as actors, and the in New York City. -

Ed Sheerans Nya Album “No.6 Collaborations Project” Ute

No.6 Collaborations Project 2019-07-12 10:23 CEST Ed Sheerans nya album “No.6 Collaborations Project” ute nu! Idag släpper Ed Sheeran sitt senaste album "No.6 Collaborations Project". Albumet består av totalt 22 samarbeten inklusive Cardi B, Camila Cabello, Khalid, Eminem, Travis Scott, Justin Bieber, Bruno Mars, Stormzy och många fler. “No.6 Collaborations Project” är ett bevis på Sheerans obestridliga talang, skicklighet som låtskrivare, musiker och inte minst samarbetspartner. Inför albumrelese släpptes totalt fem spår; ”I Don’t Care” med Justin, ”Cross Me” feat. Chance The Rapper, “Beautiful People” feat. Khalid, “BLOW” med Chris Stapleton och Bruno Mars, samt “Best Part of Me” feat. YEBBA. Inför lanseringen av det nya albumet har Ed spelat in en 50 minuter lång exklusiv intervju tillsammans med US TV och radiopersonligheten Charlamagne Tha God. Intervjun är inspelad i Eds hemmastudio och är den enda intervjun han gör kring albumet. Se YouTube-videon här Ed, som tilldelades ett MBE för sina tjänster inom musik och välgörenhet i slutet av 2017 och krönt till IFPI:s bäst säljande artist i samma år, är vinnare av totalt fyra Grammy Awards, fyra Ivor Novello, sex BRIT Awards, sju Billboard Awards, med mera. Låtlista – “No.6 Collaborations Project” 1. Beautiful People feat. Khalid 2. South of the Border feat. Camila Cabello & Cardi B 3. Cross Me feat. Chance the Rapper and PnB Rock 4. Take Me Back to London feat. Stormzy 5. Best Part of Me feat. YEBBA 6. I Don’t Care with Justin Bieber 7. Antisocial with Travis Scott 8. Remember the Name feat. -

J. Tillman Release Date: 09/22/2009 CD UPC Year in the Kingdom 6 56605 46022 2

a WESTERN VINYL release WV068 || Format: CD J. Tillman Release Date: 09/22/2009 CD UPC Year In The Kingdom 6 56605 46022 2 WESTERN VINYL WWW.WESTERNVINYL.COM [email protected] SELLING POINTS - Josh will embark on his first US tour in years in November. In September he’ll tour the EU - Josh has released several critically acclaimed records and has toured in Europe and throughout 1. Year In The kingdom the US. 2. Crosswinds 3. Earthly Bodies - Features artwork by acclaimed designer and 4. Howling Light illustrator Mario Hugo 5. Though I Have Wronged You 6. Age Of Man PRESS QUOTES 7. There Is No Good In me “This is no mere side-project. His first proper UK release is a treat, at times conjuring the beautiful, stark bleakness of Nick Drake, 8. Marked In The Valley elsewhere not afraid to crank things up, as on the distortion heavy 9. Light Of The Living ‘New Imperial Grand Blues’. Best of all is the upliftingly redemptive ‘Above All Men’.” – Q Magazine “An existentialist’s songs cycle, Vacilando…’s lonely songs reinforce each other with an impeccable internal logic, fashioning its own little world-weary universe, wherein less is more, simple guitar strums signal seismic shifts in mood, shadows bump into one Year In The Kingdom unravels some kind of galactic wilderness. Tillman's 6th another. Like Neil Young’s On the Beach or Jason Molina’s Songs:Ohia incarnation, it’s best heard late at night, alone, lights album lyrically borders on mystic; proffering a transcendent union, an down low, one last glass of wine in the wings.” – Uncut effortlessness. -

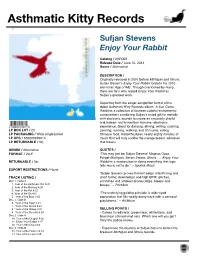

Asthmatic Kitty Records ! ! Sufjan Stevens Enjoy Your Rabbit

Asthmatic Kitty Records ! ! Sufjan Stevens Enjoy Your Rabbit Catalog / AKR003 Release Date / June 10, 2014 Genre / Alternative DESCRIPTION / Originally released in 2001 before Michigan and Illinois, Sufjan Steven’s Enjoy Your Rabbit foretells his 2010 electronic Age of Adz. Though overlooked by many, there are fans who regard Enjoy Your Rabbit as Sufjan’s greatest work. Departing from the singer-songwriter format of his debut Asthmatic Kitty Records album, A Sun Came, Rabbit is a collection of fourteen colorful instrumental compositions combining Sufjan’s noted gift for melody ! with electronic sounds to create an unusually playful and human- not to mention humane- electronic experience. Great for dancing, driving, writing, cooking, LP BOX LOT / 25 painting, running, walking, and of course, eating LP PACKAGING / Wide single jacket Chinese food, Rabbit features nearly eighty minutes of LP UPC / 656605919614 music that will truly soothe the savage breast, whatever LP RETURNABLE / No that means. GENRE / Alternative QUOTES / FORMAT / 2xLP “This may just be Sufjan Stevens' Magnus Opus. Forget Michigan, Seven Swans, Illinois . Enjoy Your RETURNABLE / No Rabbit is a masterclass in doing everything that logic tells music not to do.” – Sputnik Music EXPORT RESTRICTIONS / None “Sufjan Stevens proves himself adept of both long and TRACK LISTING / short forms; downtempo and high BPM; glitches, Disc 1 / Side A scratches and ambient drones; blips, bleeps and 1. Year of the Asthmatic Cat 0:24 bloops.” – Pitchfork 2. Year of the Monkey 4:20 3. Year of the Rat 8:22 4. Year of the Ox 4:01 “The underlying guiding principle is wide-eyed 5. -

Girl in Red - Serotonin Episode 208

Song Exploder girl in red - Serotonin Episode 208 Hrishikesh: You’re listening to Song Exploder, where musicians take apart their songs and piece by piece tell the story of how they were made. My name is Hrishikesh Hirway. Before this episode starts, I want to let you know that there is some frank discussion of mental health issues, including panic attacks, medical fears and thoughts of self-harm. There’s also some explicit language. (“Serotonin” by GIRL IN RED) Hrishikesh: Marie Ulven is a singer, songwriter, and producer from Norway, who makes music under the name, girl in red. She just released her debut album in April 2021, but she’s already got a lot of fans and she’s gotten a lot of critical acclaim from two EPs and singles that she’s released online, including a couple of songs that went gold. The New York Times included her work in their best songs of the year in both 2018 and 2019. Last year she was nominated for Best Newcomer at the Norwegian Grammys, and this year she won their award International Success of the Year. “Do you listen to girl in red?” has also become code on TikTok, a sort of shibboleth, to ask if someone’s a lesbian. In this episode, Marie breaks down the song “Serotonin,” a song that started as a video she posted to her own TikTok in the early days of lockdown in 2020. You’ll hear the original version she recorded on her own, before she started working with producer Matias Téllez, and later, with Grammy-winning artist and producer Finneas O’Connell, who helped finish the song. -

Diane Warren Seaside Release.Docx

Diane Warren’s Debut Album ‘Diane Warren: The Cave Sessions Vol. 1’ Out Now New Single & Music Video “Seaside” with Rita Ora, Sofía Reyes and REIK VIDEO HERE / ALBUM AVAILABLE HERE LOS ANGELES, CA (August 27, 2021) -- Today, songwriting legend Diane Warren unveils her debut album ‘Diane Warren: The Cave Sessions Vol. 1’ via DI-NAMIC RECORDS/BMG. Also out today is the new single & music video “Seaside”. A collaboration with global superstar Rita Ora, award-winning Mexican recording artist Sofía Reyes and Mexican pop band REIK, “Seaside” finds each artist adding their own unique flavor to the song, while the music video infuses a dynamic visual element to the Latinx-focused track. WATCH THE “SEASIDE” MUSIC VIDEO HERE The collection of 15 new original songs on ‘Diane Warren: The Cave Sessions Vol. 1’ features some of the biggest worldwide artists, including Ty Dolla $ign, Maren Morris, John Legend, Luis Fonsi, Jon Batiste, Pentatonix, G-Eazy, Carlos Santana, Rita Ora, Sofía Reyes, REIK, James Arthur, Lauren Jauregui, Jimmie Allen, LP, Celine Dion, Darius Rucker, Paloma Faith, Leona Lewis and James Morrison. “I am so excited to release this album which is like a microcosm of my career – writing songs in all kinds of genres of music for a wide range of amazing artists, many of whom I am thrilled to be working with for the first time and others with whom I’ve been delighted to work with before. I just love writing songs that reach across all genres...each song is like casting a role in a movie. But in the end, I always leave it up to the artist and how they want to do it,” says Diane Warren. -

Sony Music: Nuevos Álbumes De Louta, Carlos Vives Y Ricky Martin

Junio 2020 | Año 46 · Edición Nº 562 P × 2 Prensario Música visitanos en www.prensariomusica.com nuestras redes sociales @prensariomusica Prensario Música P × 3 Junio 2020 | Año 46 · Edición Nº 562 P × 2 Prensario Música visitanos en www.prensariomusica.com nuestras redes sociales @prensariomusica Prensario Música P × 3 Editorial Junio 2020 | Año 46 · Edición Nº 562 AGENDA • SHOWBUSINESS • PRODUCTORAS LÍDERES • ARGENTINA Se aprobaron los shows por POR ALEJO SMIRNOFF streaming en los venues líderes Instagram: alejoprensario [email protected] Mientras todas las ticketeras principales E-mail: SPONSORS lanzaron la modalidad Live/Play DESTACADOS Justo cuando se extendió la cuarentena, una gran Todos ellos se sumaron a Ticket Hoy, otro re- noticia para el showbusiness, fue la aprobación del portaje de esta edición de Prensario Música y que 2020 Del LAMC al Seminario protocolo para la emisión de shows por streaming participará en nuestro seminario junto a Dataxis del en los principales venues en CABA y otras ciudades. 25 de junio, que se posicionó antes que ninguna en vivo de Dataxis En otros años está noticia no hubiera sido re- en esta era del streaming con los independientes. Flow/Telecom levante, pero en este momento implica, un gran Un tema recurrente es el del precio que se puede Lolapalooza, BSB, Metal- Esta nueva edición digital de Prensario nuestros países fue pequeña con Sebastián de primer logro, especialmente de la asociación de cobrar, que es más barato que lo que se puede lica, Kiss- DF Música destaca las primeras conquistas con el la Barra de Lotus de Chile y artistas como Ca- managers ACCMA y AADET, de los promotores, cobrar en un venue, pero por ahora es totalmente streaming frente a la cuarentena, reportajes ligaris, Francisca Valenzuela y Denis Rosenthal ante el gobierno y la sociedad en general. -

Ver Fuerte Ranking Top 3: Livenation, Del Rock in Rio

Julio 2019 | Año 45 · Edición Nº 551 P × 2 Prensario Música visitanos en www.prensariomusica.com nuestras redes sociales @prensariomusica Prensario Música P × 3 Julio 2019 | Año 45 · Edición Nº 551 P × 2 Prensario Música visitanos en www.prensariomusica.com nuestras redes sociales @prensariomusica Prensario Música P × 3 Editorial Julio 2019 | Año 45 · Edición Nº 551 AGENDA • SHOWBUSINESS • PRODUCTORAS LÍDERES • ARGENTINA Muse, Slayer, Megadeth, King Crimson y POR ALEJO SMIRNOFF muchos más en la Movida del Rock in Rio EN LO NACIONAL SOBRESALE LAS GIRAS DE ANDRÉS CALAMARO Y LUCIANO PEREYRA Se siguen dando los grandes anuncios del LAURIA se mantiene entre los que más produ- segundo semestre de las promotoras líderes, con cen; tiene a Reik el 31 de agosto en el Luna Park el viento a favor del flujo de artistas que vendrá con el Banco Comafi, además de volver fuerte Ranking Top 3: LiveNation, del Rock in Rio. De ese flujo, como dijimos el mes para los chicos en las vacaciones con Shopkins pasado por su vínculo societario con LiveNation, y PeppaPig en el Metropolitan. Banco Makro está SPONSORS DESTACADOS el que más contenido va a captar es DF Entertain- armando su plataforma, que incluye toda la gira Abril - Mayo - Junio 2019 AEG y OCESA ment, que ya anunció a Muse el 11 de octubre en de Diego Torres. el Hipódromo de Palermo. Pero no fue un anuncio más pues trae dos nuevas plataformas: Flow En el BA Arena, el Luna Park, Gran BBVA Francés Music XP en una interesante unión de sponsor y IronMaiden, Dido, Shawn Rex y Opera Orbis Seguros Mendes – Move > Sumario, en esta edición tecnología para nuevas comercializaciones, y la Además, en la pujante segunda línea de Richard Marx - Pash En la transformación que venimos haciendo en la página 5 siguiente. -

Canciones + Streaming Anual 2020

TOP 100 CANCIONES + STREAMING ANUAL 2020 (Las ventas totales corresponden a los datos enviados por colaboradores habituales de venta física y por los siguientes operadores: Amazon, Amazon Music, i-Tunes, 7Digital, Apple Music, Deezer, Spotify,Napster y Tidal) Sem. Cert. Cert. Anual Lista Artista Título Sello 2020 Acumulados 1 60 KAROL G / NICKI MINAJ TUSA UNIVERSAL 7** 8** 2 60 FRED DE PALMA / ANA MENA SE ILUMINABA WARNER MUSIC 5** 5** 3 54 THE WEEKND BLINDING LIGHTS UNIVERSAL 4** 4** 4 22 MALUMA HAWÁI SONY MUSIC 4** 4** 5 68 TONES AND I DANCE MONKEY WARNER MUSIC 5** 6** 6 36 NIO GARCIA / ANUEL AA / MYKE TOWERS / NIO GARCIA / BRRAYLA JEEPETA / (REMIX) FLOW LA MOVIE, INC / POWERED BY GLAD3** EMP 3** 7 39 FEID / JUSTIN QUILES PORFA UNIVERSAL 3** 3** 8 29 OZUNA CARAMELO AURA / SONY MUSIC 3** 3** 9 29 JAY WHEELER / DJ NELSON / MYKE TOWERS LA CURIOSIDAD LINKED MUSIC / EMPIRE 3** 3** 10 25 RAUW ALEJANDRO / CAMILO TATTOO SONY MUSIC 3** 3** 11 9 BAD BUNNY / JHAY CORTEZ DAKITI RIMAS ENTERTAINMENT LLC 3** 3** 12 35 CHEMA RIVAS MIL TEQUILAS CHEMA RIVAS 3** 3** 13 30 J. BALVIN MORADO UNIVERSAL 3** 3** 14 28 BAD BUNNY / JOWELL / RANDY / ÑENGO FLOW SAFAERA RIMAS ENTERTAINMENT LLC 3** 3** 15 39 CAMILO FAVORITO SONY MUSIC 3** 3** 16 44 AITANA / CALI Y EL DANDEE + UNIVERSAL 3** 3** 17 8 C. TANGANA / NIÑO DE ELCHE / LA HUNGARA TÚ ME DEJASTE DE QUERER SONY MUSIC 3** 3** 18 46 AYA NAKAMURA DJADJA WARNER MUSIC 3** 4** 19 29 ANUEL AA EL MANUAL REAL HASTA LA MUERTE / SONY MUSIC3** 3** 20 44 OMAR MONTES / BAD GYAL ALOCAO UNIVERSAL 3** 5** 21 4 RAUW ALEJANDRO TATTOO DUARS ENTERTAINMENT 3** 3** 22 29 J BALVIN ROJO UNIVERSAL 3** 3** 23 34 SHAKIRA / ANUEL AA ME GUSTA SONY MUSIC 3** 3** 24 30 PRINCE ROYCE / MYKE TOWERS CARITA DE INOCENTE (REMIX) SONY MUSIC 3** 3** 25 24 JUSTIN QUILES / DADDY YANKEE / EL ALFA PAM WARNER MUSIC 3** 3** 26 27 MYKE TOWERS DIOSA CASABLANCA RECORDS & ONE WORLD2** MUSIC 2** 27 27 J. -

“El Mal Querer De Rosalía: Análisis Estético, Audiovisual E Interpretativo”

UNIVERSIDAD POLITECNICA DE VALENCIA ESCUELA POLITECNICA SUPERIOR DE GANDIA “El mal querer de Rosalía: análisis estético, audiovisual e interpretativo” TRABAJO FINAL DE GRADO Autor/a: Silvia Vaquero Tramoyeres Tutor/a: Nadia Alonso López GANDIA, 2020 1 Resumen En 2018 la cantante Rosalía publicó el álbum que la ha llevado a la fama mundial, titulado El mal querer. Este disco ha resultado ser un producto interesante más allá de lo puramente musical y comercial, destacando en la estética, elementos audiovisuales y simbología empleada. Destaca un factor decisivo en la creación del álbum El mal querer, que es la clara inspiración que ha tomado la cantante Rosalía de Flamenca, una obra literaria occitana, de autoría anónima y que data del siglo XIII. No obstante, pese a ser una novela medieval, Rosalía ha visto la actualidad de la historia y de la heroína, y ha sabido llevarla al mundo de hoy en día, un mundo en el que las relaciones interpersonales, la toxicidad que puede haber en estas y la figura de la mujer no han cambiado tanto. De esta forma, la historia del medievo ha servido para dar estructura al álbum y conformar un hilo narrativo que se desarrolla de manera fragmentaria desde la primera canción hasta la última. Asimismo, la acción contada se lleva a cabo también en el ámbito audiovisual, en el que la fusión de elementos del pasado y la cultura actual se hace efectiva y visible. De este modo, este documento constituye una interpretación del álbum El mal querer, tanto desde su nivel literario y narrativo, atendiendo a qué se cuenta y de qué manera se cuenta, hasta el audiovisual. -

Fighting the Epidemic Godwin Organization Works to Combat Drug Abuse Within Schools

The Eagles’ Volume 38 Mills E. Godwin High School Issue 7 2101 Pump Road April 27, 2018 Richmond, Virginia 23238 Eyrie Priceless godwineagles.org Fighting the epidemic Godwin organization works to combat drug abuse within schools photo Eagles’ Eyrie 2016 photo Kathryn Chamberlin l to r: Harrison Derr, Jenny Derr, Chris Herren, and Jordan Derr at the Chris Herren drug A Project Purple meeting on April 23. School leaders met awareness assembly in 2016. Jenny Derr spoke about her late son Billy. to speak about substance abuse at Godwin. are facing substance abuse ings, as well as having speakers Ben Grott tinued to struggle with addiction, ented man who loved sports and issues. Also around that time, talk at lunches. News Editor seeing counselors, and eventu- popular rap culture. Derr and other parents contin- Project Purple also participat- Today, addiction touches the ally entered a full time treatment Derr decided the only way to ued to meet as they prepared ed in Red Ribbon Week, where lives of many, even the God- facility in 2014. make change was for their family for Chris Herren, a retired NBA Derr and Anne Moss Rogers, an win community. The desire for Billy then relapsed after a to start raising awareness and player, addict and now motiva- addiction, suicide, and mental change led to the creation of year and a half of sobriety in sharing Billy’s story. tional speaker, to come and talk illness speaker, talked about project purple 2016, but seemed to be back “I remember calling Billy and to the Godwin community. -

ARTIST INDEX(Continued)

ChartARTIST Codes: CJ (Contemporary Jazz) INDEXINT (Internet) RBC (R&B/Hip-Hop Catalog) –SINGLES– DC (Dance Club Songs) LR (Latin Rhythm) RP (Rap Airplay) –ALBUMS– CL (Traditional Classical) JZ (Traditional Jazz) RBL (R&B Albums) A40 (Adult Top 40) DES (Dance/Electronic Songs) MO (Alternative) RS (Rap Songs) B200 (The Billboard 200) CX (Classical Crossover) LA (Latin Albums) RE (Reggae) AC (Adult Contemporary) H100 (Hot 100) ODS (On-Demand Songs) STS (Streaming Songs) BG (Bluegrass) EA (Dance/Electronic) LPA (Latin Pop Albums) RLP (Rap Albums) ARB (Adult R&B) HA (Hot 100 Airplay) RB (R&B Songs) TSS (Tropical Songs) BL (Blues) GA (Gospel) LRS (Latin Rhythm Albums) RMA (Regional Mexican Albums) CA (Christian AC) HD (Hot Digital Songs) RBH (R&B Hip-Hop) XAS (Holiday Airplay) APR CA (Country) HOL (Holiday) NA (New Age) TSA (Tropical Albums) CS (Country) HSS (Hot 100 Singles Sales) RKA (Rock Airplay) XMS (Holiday Songs) CC (Christian) HS (Heatseekers) PCA (Catalog) WM (World) CST (Christian Songs) LPS (Latin Pop Songs) RMS (Regional Mexican Songs) 24 CCA (Country Catalog) IND (Independent) RBA (R&B/Hip-Hop) DA (Dance/Mix Show Airplay) LT (Hot Latin Songs) RO (Hot Rock Songs) 2021 $NOT HS 19, 22 JUSTIN BIEBER B200 3; CC 8; DLP 11; RBL 25; J. COLE B200 68; PCA 14; RBA 37 LUIS FIGUEROA TSS 21 STEPHEN HOUGH CL 11 LYDIA LAIRD CA 29; CST 33 21 SAVAGE B200 103; RBH 49 A40 13, 26; AC 9, 16, 20; CST 23, 26, 35, 36, KEYSHIA COLE ARB 14 FINNEAS A40 36; AK 18; RO 20 WHITNEY HOUSTON B200 197; RBL 22 LAKE STREET DIVE RKA 46 24KGOLDN B200 65; A40 4; AC 25;