Effect of Rotigotine Vs Placebo on Cognitive Functions Among Patients with Mild to Moderate Alzheimer Disease a Randomized Clinical Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modulation by Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1 of Experimental Parkinsonism, L-DOPA Responsivity, and Glutamatergic Neurotransmission

The Journal of Neuroscience, October 14, 2015 • 35(41):14057–14069 • 14057 Neurobiology of Disease Modulation by Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1 of Experimental Parkinsonism, L-DOPA Responsivity, and Glutamatergic Neurotransmission Alexandra Alvarsson,1* Xiaoqun Zhang,1* Tiberiu L Stan,1 Nicoletta Schintu,1 Banafsheh Kadkhodaei,2 Mark J. Millan,3 Thomas Perlmann,2,4 and Per Svenningsson1 1Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Center for Molecular Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, SE-17176 Stockholm, Sweden, 2Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, SE-17177 Stockholm, Sweden, 3Pole of Innovation in Neuropsychiatry, Institut de Recherches Servier, Centre de Recherches de Croissy, Paris 87290, France, and 4Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, Karolinska Institutet, SE-17177 Stockholm, Sweden Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a movement disorder characterized by a progressive loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons. Restoration of dopamine transmission by L-DOPA relieves symptoms of PD but causes dyskinesia. Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1 (TAAR1) modulates dopaminergic transmission, but its role in experimental Parkinsonism and L-DOPA responses has been neglected. Here, we report that TAAR1 knock-out (KO) mice show a reduced loss of dopaminergic markers in response to intrastriatal 6-OHDA administra- tion compared with wild-type (WT) littermates. In contrast, the TAAR1 agonist RO5166017 aggravated degeneration induced by intra- striatal6-OHDAinWTmice.Subchronic L-DOPAtreatmentofTAAR1KOmiceunilaterallylesionedwith6-OHDAinthemedialforebrain bundle resulted in more pronounced rotational behavior and dyskinesia than in their WT counterparts. The enhanced behavioral sensitization to L-DOPA in TAAR1 KO mice was paralleled by increased phosphorylation of striatal GluA1 subunits of AMPA receptors. Conversely, RO5166017 counteracted both L-DOPA-induced rotation and dyskinesia as well as AMPA receptor phosphorylation. -

The Use of Illicit Drugs As Self-Medication in the Treatment of Cluster Headache: Results from an Italian Online Survey

XML Template (2015) [21.4.2015–2:34pm] [1–5] //blrnas3.glyph.com/cenpro/ApplicationFiles/Journals/SAGE/3B2/CEPJ/Vol00000/150048/APPFile/SG-CEPJ150048.3d (CEP) [PREPRINTER stage] Original Article Cephalalgia 0(0) 1–5 ! International Headache Society 2015 The use of illicit drugs as self-medication Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav in the treatment of cluster headache: DOI: 10.1177/0333102415583145 Results from an Italian online survey cep.sagepub.com C Di Lorenzo1, G Coppola2, G Di Lorenzo3, M Bracaglia4, P Rossi5 and F Pierelli4,6 Abstract Background: Cluster headache (CH) patients often receive unsatisfactory treatment and may explore illicit substances as alternatives. We aimed to explore this use of illicit drugs for CH treatment. Methods: We invited CH patients from an Internet-based self-help group to complete a questionnaire regarding their therapeutic use of illicit substances. Results: Of the 54 respondents, 29 were classified as chronic and 39 were drug-resistant cases. Fifty patients had previously tried subcutaneous sumatriptan, 40 had tried O2, and 48 had tried at least one prophylactic treatment. All 54 patients specified that they were dissatisfied with conventional treatments. Thirty-four patients had used cannabin- oids, 13 cocaine, 8 heroin, 18 psilocybin, 12 lysergic acid amide (LSA), and 4 lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Discussion: Some patients with intractable CH decided to try illicit drugs concomitantly with cessation of medical care. Most of these patients found suggestions for illicit drug use on the Internet. Many patients seemed to underestimate the judicial consequences of, and had an overestimated confidence in the safety of, such illicit treatments. -

Endogenous Metabolites in Drug Discovery: from Plants to Humans

Endogenous Metabolites in Drug Discovery: from Plants to Humans Joaquim Olivés Farrés TESI DOCTORAL UPF / ANY 201 6 DIRECTOR DE LA TESI: Dr. Jordi Mestres CEXS Department The research in this T hesis has been carried out at the Systems Pharmacolo gy Group , within the Research Programme on Biomedical Informatics (GRIB) at the Parc de Recerca Biomèdica de Barcelona (PRBB). The research presented in this T hesis has been supported by Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación project BIO2014 - 54404 - R and BIO2011 - 26669 . Printing funded by the Fundació IMIM’s program “Convocatòria d'ajuts 2016 per a la finalització de tesis doctorals de la Fundació IMIM.” Agraïments Voldria donar les gràcies a tanta gent que em fa por deixar - me ningú. Però per c omençar haig agrair en especial al meu director la tesi, Jordi Mestres, per donar - me la oportunitat de formar part del seu laboratori i poder desenvolupar aquí el treball que aquí es presenta. A més d’oferir l’ajuda necessària sempre que ha calgut. També haig de donar les gràcies a tots els companys del grup de Farmacologia de Sistemes que he anat coneguent durants tots aquests anys en què he estat aquí, en especial en Xavi, a qui li he preguntat mil coses, en Nikita, pels sdfs que m’ha anat llençant a CTL ink, i la Irene i la Cristina, que els seus treballs també m’ajuden a completar la tesis. I cal agrair també a la resta de companys del laboratori, l’Albert, la Viktoria, la Mari Carmen, l’Andreas, en George, l’Eric i l’Andreu; de Chemotargets, en Ricard i en David; i altres membres del GRIB, com són l’Alfons, en Miguel, en Pau, l’Oriol i la Carina. -

Crystal Structure of Dopamine D1 Receptor in Complex with G Protein and a Non-Catechol Agonist

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23519-9 OPEN Crystal structure of dopamine D1 receptor in complex with G protein and a non-catechol agonist Bingfa Sun 1,7, Dan Feng1,7, Matthew Ling-Hon Chu1, Inbar Fish1, Silvia Lovera2, Zara A. Sands2,6, Sebastian Kelm 3, Anne Valade2, Martyn Wood2, Tom Ceska 3, Tong Sun Kobilka1, Florence Lebon4 & ✉ Brian K. Kobilka 1,5 Dopamine D1 receptor (D1R) is an important drug target implicated in many psychiatric and 1234567890():,; neurological disorders. Selective agonism of D1R are sought to be the therapeutic strategy for these disorders. Most selective D1R agonists share a dopamine-like catechol moiety in their molecular structure, and their therapeutic potential is therefore limited by poor pharmaco- logical properties in vivo. Recently, a class of non-catechol D1R selective agonists with a distinct scaffold and pharmacological properties were reported. Here, we report the crystal structure of D1R in complex with stimulatory G protein (Gs) and a non-catechol agonist Compound 1 at 3.8 Å resolution. The structure reveals the ligand bound to D1R in an extended conformation, spanning from the orthosteric site to extracellular loop 2 (ECL2). Structural analysis reveals that the unique features of D1R ligand binding pocket explains the remarkable selectivity of this scaffold for D1R over other aminergic receptors, and sheds light on the mechanism for D1R activation by the non-catechol agonist. 1 ConfometRx, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA. 2 UCB Pharma, Braine-l’Alleud, Belgium. 3 UCB Pharma, Slough, UK. 4 UCB Pharma, Anderlecht, Belgium. 5 Department of Molecular and Cellular Physiology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA. -

An Improved Validated Ultra High Pressure Liquid Chromatography Method for Separation of Rotigotine Impurities in Rotigotine Transdermal Patch

Available online a t www.derpharmachemica.com Scholars Research Library Der Pharma Chemica, 2015, 7(5):26-34 (http://derpharmachemica.com/archive.html) ISSN 0975-413X CODEN (USA): PCHHAX An improved validated ultra high pressure liquid chromatography method for separation of Rotigotine impurities in Rotigotine Transdermal Patch *Avinash S. Patil 1, Shakil S. Sait 2, Girish Deshpande 1, Prakashkumar Acharya 1 and Veeravenkata Srikanth Kaki 1 1Mylan Laboratories Ltd., Formulation AR&D, Plot No. 34 A & B, ANRICH Industrial Estate Bollaram Jinnaram (Mandal), Medak District, Hyderabad, India 2Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd., Generics A R &D, Innovation Plaza, Survey Nos. 42,45,46 & 54, Bachupalli, Qutubllapur, RR dist, AP, India _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT A rapid, specific, sensitive ultra high-performance liquid chromatographic (UPLC) method has been developed for determination of Rotigotine impurities and its degradation products in Rotigotine Transdermal Patches. UPLC was performed on a C18 column with “mobile phase A” consist of pH 10.00 buffer solution while “mobile phase B” consist of Acetonitrile. The mobile phase was pumped in a gradient manner at the flow-rate of 0.4 mL min −1 . Ultraviolet detection was performed at 225 nm. Rotigotine impurities and degradation products along with process impurities were chromatographed with a total run time of 30 minutes. Calibration showed that response of impurities was a linear function of concentration over the range LOQ to 200% of the target concentration (r 2 ≥ 0.999) and the method was validated over this range for precision, accuracy, linearity and specificity. For precision study, percentage relative standard deviation of each impurity was <15% (n = 6). -

WO 2009/147681 Al

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date 10 December 2009 (10.12.2009) WO 2009/147681 Al (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 45/06 (2006.01) A61K 31/137 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, A61P 25/16 (2006.01) A61K 31/4045 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, A61K 31/135 (2006.01) A61K 31/428 (2006.01) CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (21) International Application Number: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, PCT/IL2009/000567 KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, (22) International Filing Date: ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, 7 June 2009 (07.06.2009) NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, (25) Filing Language: English TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (26) Publication Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (30) Priority Data: kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, 61/059,326 6 June 2008 (06.06.2008) US GM, KE, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): PHAR- TM), European (AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, MA TWO B LTD. -

In-Silico Approaches

molecules Review Recent Developments in New Therapeutic Agents against Alzheimer and Parkinson Diseases: In-Silico Approaches Pedro Cruz-Vicente 1,2 , Luís A. Passarinha 1,2,3,* , Samuel Silvestre 1,3,4,* and Eugenia Gallardo 1,3,* 1 CICS-UBI, Health Sciences Research Centre, University of Beira Interior, 6201-001 Covilhã, Portugal; [email protected] 2 UCIBIO—Applied Molecular Biosciences Unit, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Sciences and Technology, NOVA University Lisbon, 2829-516 Caparica, Portugal 3 Laboratory of Pharmaco-Toxicology—UBIMedical, University of Beira Interior, 6200-001 Covilhã, Portugal 4 CNC—Center for Neuroscience and Cell Biology, University of Coimbra, 3004-504 Coimbra, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected] (L.A.P.); [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (E.G.); Tel.: +351-275-329-002/3 (L.A.P. & S.S. & E.G.) Abstract: Neurodegenerative diseases (ND), including Alzheimer’s (AD) and Parkinson’s Disease (PD), are becoming increasingly more common and are recognized as a social problem in modern societies. These disorders are characterized by a progressive neurodegeneration and are considered one of the main causes of disability and mortality worldwide. Currently, there is no existing cure for AD nor PD and the clinically used drugs aim only at symptomatic relief, and are not capable Citation: Cruz-Vicente, P.; of stopping neurodegeneration. Over the last years, several drug candidates reached clinical trials Passarinha, L.A.; Silvestre, S.; phases, but they were suspended, mainly because of the unsatisfactory pharmacological benefits. Gallardo, E. Recent Developments in Recently, the number of compounds developed using in silico approaches has been increasing at New Therapeutic Agents against a promising rate, mainly evaluating the affinity for several macromolecular targets and applying Alzheimer and Parkinson Diseases: filters to exclude compounds with potentially unfavorable pharmacokinetics. -

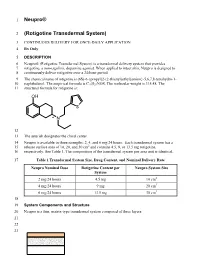

Neupro® (Rotigotine Transdermal System) Is a Transdermal Delivery System That Provides 7 Rotigotine, a Non-Ergolinic Dopamine Agonist

1 Neupro® 2 (Rotigotine Transdermal System) 3 CONTINUOUS DELIVERY FOR ONCE-DAILY APPLICATION 4 Rx Only 5 DESCRIPTION 6 Neupro® (Rotigotine Transdermal System) is a transdermal delivery system that provides 7 rotigotine, a non-ergolinic dopamine agonist. When applied to intact skin, Neupro is designed to 8 continuously deliver rotigotine over a 24-hour period. 9 The chemical name of rotigotine is (6S)-6-{propyl[2-(2-thienyl)ethyl]amino}-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-1- 10 naphthalenol. The empirical formula is C19H25NOS. The molecular weight is 315.48. The 11 structural formula for rotigotine is: OH S * N 12 13 The asterisk designates the chiral center. 14 Neupro is available in three strengths: 2, 4, and 6 mg/24 hours. Each transdermal system has a 15 release surface area of 10, 20, and 30 cm2 and contains 4.5, 9, or 13.5 mg rotigotine, 16 respectively. See Table 1. The composition of the transdermal system per area unit is identical. 17 Table 1 Transdermal System Size, Drug Content, and Nominal Delivery Rate Neupro Nominal Dose Rotigotine Content per Neupro System Size System 2 mg/24 hours 4.5 mg 10 cm2 4 mg/24 hours 9 mg 20 cm2 6 mg/24 hours 13.5 mg 30 cm2 18 19 System Components and Structure 20 Neupro is a thin, matrix-type transdermal system composed of three layers: 21 22 23 24 Backing film 25 Drug matrix 26 Protective liner 27 28 1. A flexible, tan-colored backing film, consisting of an aluminized polyester film coated with a 29 pigment-layer on the outer side. -

Acute Management of In-Patient Parkinson's Disease Patients

NHS Fife Acute Management of Patient’s with Parkinson’s Disease Acute management of in-patient Parkinson’s Disease patients Contents Pages Introduction and Admission advice 2 Nil by Mouth Guidance 3 – 5 Complex therapy advice (Apomorphine, DBS, Duodopa) 6 Surgical peri-operative advice 7 Contacts/Directory 7 Author:- Ewan Tevendale, Nicola Chapman, Lynda Kearney Approved by the Managed Services Drug and Therapeutics Committee August 2017. (Review date August 2019) Page 1 NHS Fife Acute Management of Patient’s with Parkinson’s Disease Introduction Medication is crucial in optimal management of Parkinson’s. If medication is not given this can result in compromised swallow (increasing risk of aspiration), delirium, speech difficulties, immobility and hence more dependence. It can also lead to increased falls in a population at high risk of fractures. At worst they may develop a Neuroleptic Malignant Type Syndrome which can be fatal. People with Parkinson’s are admitted to hospital for numerous reasons. Often these are unrelated to their Parkinson’s but if not managed appropriately on admission this can lead to delayed recovery, delayed discharge and poor outcomes for patients and their families. This document has been devised to provide guidance to staff who are involved in the care of someone with Parkinson’s admitted to hospital for whatever reason should the Parkinson’s Specialist Team be unavailable. (e.g. weekend or out of hours) It should be highlighted that these guidelines provide advice to medical and nursing staff to ensure people with Parkinson’s are managed appropriately on admission i.e. receive some anti- parkinsonian medication until they can be seen by a member of the Parkinson’s Team to provide specialist advice on complex medicines management. -

Prescription Medications, Drugs, Herbs & Chemicals Associated With

Prescription Medications, Drugs, Herbs & Chemicals Associated with Tinnitus American Tinnitus Association Prescription Medications, Drugs, Herbs & Chemicals Associated with Tinnitus All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, or by any means, without the prior written permission of the American Tinnitus Association. ©2013 American Tinnitus Association Prescription Medications, Drugs, Herbs & Chemicals Associated with Tinnitus American Tinnitus Association This document is to be utilized as a conversation tool with your health care provider and is by no means a “complete” listing. Anyone reading this list of ototoxic drugs is strongly advised NOT to discontinue taking any prescribed medication without first contacting the prescribing physician. Just because a drug is listed does not mean that you will automatically get tinnitus, or exacerbate exisiting tinnitus, if you take it. A few will, but many will not. Whether or not you eperience tinnitus after taking one of the listed drugs or herbals, or after being exposed to one of the listed chemicals, depends on many factors ‐ such as your own body chemistry, your sensitivity to drugs, the dose you take, or the length of time you take the drug. It is important to note that there may be drugs NOT listed here that could still cause tinnitus. Although this list is one of the most complete listings of drugs associated with tinnitus, no list of this kind can ever be totally complete – therefore use it as a guide and resource, but do not take it as the final word. The drug brand name is italicized and is followed by the generic drug name in bold. -

Behavioral Pharmacology of Dopamine D2 and D3 Receptor Agonists and Antagonists in Rats

Behavioral Pharmacology of Dopamine D2 and D3 Receptor Agonists and Antagonists in Rats. by Gregory T. Collins A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Pharmacology) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor James H. Woods, Chair Professor Margaret E. Gnegy Professor Shaomeng Wang Assistant Professor Roger K. Sunahara © Gregory T. Collins 2008 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my parents, Thomas and Shirley Collins, without whom none of this would have been possible. Your continual support and encouragement throughout all of my endeavors has meant more than you will ever know. Thank you. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my mentor, James Woods. You have been an exceptional mentor to me; I have learned more than I could have ever hoped. It has been a pleasure to work with someone who is so passionate and knowledgable, someone who has not only continued to challenge me, but has also provided an outstanding environment in which to study behavioral pharmacolgy. I truly feel lucky to have been able to learn from you. Of course, I also have to thank Gail Winger who has been a second mentor to me throughout the years. The support, encouragement, guidance, and patience that the two of you have provided has made for an exceptional experience. Thank you. I would also like to thank my committee, James Woods, Roger Sunahara, Peggy Gnegy and Shaomeng Wang. I am grateful to have been able to work with and learn from all of you over the years. -

Side Effects of a Dopamine Agonist Therapy for Parkinson's Disease

YALE JOURNAL OF BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE 89 (2016), pp. 37-47. ReView Side effects of a dopamine agonist therapy for Parkinson’s disease: a mini-review of clinical pharmacology Josip Anđelo Borovac* Department of Pathophysiology, University of Split School of Medicine, Croatia, EU Dopamine agonists (DA) are therapeutic agents that are commonly used in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease (PD). They can reduce undesired motor fluctuations and delay the administration of levodopa ther- apy. However, this drug family is associated with specific side effects that can significantly diminish the quality of life among PD patients. Some of them impose significant risks for individuals who have a his- tory of cardiovascular diseases, psychosis, and depression, or those older patients who suffer from renal or hepatic insufficiency. Various pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations need to be taken into account when administering DA therapy. The goal of this review is to provide a comprehensive, up-to-date overview of DA therapeutic modalities for PD. INTRODUCTION are mediated by the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and domi- nantly implicated in reward and reinforcement pathways Dopamine agonists (DA) are chemical compounds (D3 to a lesser degree) [6,7]. it is reasonable to assume that that bind to dopamine receptors in the absence of the en- D2 receptors play an important role in psychotic behaviors dogenous neurotransmitter dopamine. Dopamine recep- since all efficacious antipsychotic drugs have the ability to tors are abundantly expressed in many tissues in the body, antagonize D2 receptors. The dopamine D3 receptor, lo- predominantly in the brain. Two families of dopamine re- cated in the limbic area of the brain, mediates drug-seek- ceptors have been identified.