A Fatal Case of Coxsackievirus B4 Meningoencephalitis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Picture of the Month

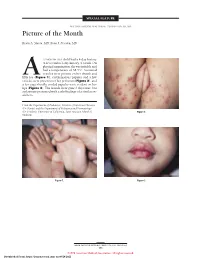

SPECIAL FEATURE SECTION EDITOR: WALTER W. TUNNESSEN, JR, MD Picture of the Month Kevin A. Slavin, MD; Ilona J. Frieden, MD 15-MONTH-OLD child had a 4-day history of fever and a 1-day history of a rash. On physical examination she was irritable and had a temperature of 38.3°C. Scattered vesicles were present on her thumb and Afifth toe (Figure 1), erythematous papules and a few vesicles were present over her perineum (Figure 2), and a few superficially eroded papules were evident on her lips (Figure 3). The lesions were gone 3 days later, but a playmate presented with early findings of a similar ex- anthem. From the Department of Pediatrics, Division of Infectious Diseases (Dr Slavin) and the Department of Pediatrics and Dermatology (Dr Frieden), University of California, San Francisco School of Figure 2. Medicine. Figure 1. Figure 3. ARCH PEDIATR ADOLESC MED/ VOL 152, MAY 1998 505 ©1998 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Denouement and Discussion Hand-Foot-and-Mouth Disease Figure 1. Vesicles are present on the thumb and fifth toe. foot-and-mouth disease).1,2,5-9 The lesions on the but- tocks are of the same size and typical of the early forms Figure 2. Multiple erythematous papules and a few scattered vesicles are of the exanthem, but they are not frequently vesicular present over the perineum. in nature. Lesions involving the perineum seem to be more Figure 3. Superficially eroded papules are present on the lips. common in children who wear diapers, suggesting that friction or minor trauma may play a role in the develop- ment of lesions. -

Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease (Coxsackievirus) Fact Sheet

Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease (Coxsackievirus) Fact Sheet Hand, foot, and mouth disease is caused by one of several types of viruses Hand, foot, and mouth disease is usually characterized by tiny blisters on the inside of the mouth and the palms of the hands, fingers, soles of the feet. It is commonly caused by coxsackievirus A16 (an enterovirus), and less often by other types of viruses. Anyone can get hand, foot, and mouth disease Young children are primarily affected, but it may be seen in adults. Most cases occur in the summer and early fall. Outbreaks may occur among groups of children especially in child care centers or nursery schools. Symptoms usually appear 3 to 5 days after exposure. Hand, foot, and mouth disease is usually spread through person-to-person contact People can spread the disease when they are shedding the virus in their feces. It is also spread by the respiratory tract from mouth or respiratory secretions (such as from saliva on hands or toys). The virus has also been found in the fluid from the skin blisters. The infection is spread most easily during the acute phase/stage of illness when people are feeling ill, but the virus can be spread for several weeks after the onset of infection. The symptoms are much like a common cold with a rash The rash appears as blisters or ulcers in the mouth, on the inner cheeks, gums, sides of the tongue, and as bumps or blisters on the hands, feet, and sometimes other parts of the skin. The skin rash may last for 7 to 10 days. -

An Epidemic of Acute Encephalitis in Young Children

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.9.51.153 on 1 June 1934. Downloaded from AN EPIDEMIC OF ACUTE ENCEPHALITIS IN YOUNG CHILDREN BY AGNES R. MACGREGOR, M.B., F.R.C.P.E., AND W. S. CRAIG, B.Sc., M.D., M.R.C.P.E. (From the Departments of Pathology and Child Life and Health, Univer- sity of Edinburgh, and the Western General Hospital, Edinburgh.) This paper is concerned with a small outbreak of illness of an unusual nature occurring in the Children's Unit of the Western General Hospital, Edinburgh. In addition to the clinical interest of the cases, there are features of considerable pathological and epidemiological importance con- nected with the outbreak. Clinical Records. Case 1. I.M.S., female, aged 1 year 7 months, was admitted to the Western General Hospital in March, 1933, at the age of 1 year 3 months. - At this time http://adc.bmj.com/ she was noted as being slightly undersized but well nourished and the liver showed moderate enlargement. Prior to admission she had been treated elsewhere for gonococcal vaginitis: during the three succeeding months her health was good and progress uninterrupted, but a positive Wassermann reaction, present on admission, persisted. On the evening of July 22, 1933, the patient was noticed to be less active than usual and generally ' out of sorts ': her conditiQn remained unchanged throughout the rest of the day, and on the 23rd she was 'Ptill quieter and less responsive to all forms of attention and refused food. By the afternoon on October 2, 2021 by guest. -

A Guide to Clinical Management and Public Health Response for Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease (HFMD)

A Guide to Clinical Management and Public Health Response for Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease (HFMD) WHO Western Pacific Region PUBLICATION ISBN-13 978 92 9061 525 5 A Guide to Clinical Management and Public Health Response for Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease (HFMD) WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A Guide to clinical management and public health response for hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) 1. Hand, foot and mouth disease – epidemiology. 2. Hand, foot and mouth disease – prevention and control. [ ii ] 3. Disease outbreaks. 4. Enterovirus A, Human. I. Regional Emerging Disease Intervention Center. ISBN 978 92 9061 525 5 (NLM Classification: WC 500) © World Health Organization 2011 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). For WHO Western Pacific Regional Publications, request for permission to reproduce should be addressed to the Publications Office, World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Western Pacific, P.O. Box 2932, 1000, Manila, Philippines, (fax: +632 521 1036, e-mail: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Encephalitis Lethargica

flra/n (1987), 110, 19-33 ENCEPHALITIS LETHARGICA A REPORT OF FOUR RECENT CASES Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/brain/article/110/1/19/273787 by guest on 01 October 2021 by R. s. HOWARD and A. J. LEES (From The National Hospital for Nervous Diseases, Queen Square, London) SUMMARY Four patients are described with an encephalitic illness identical to that described by von Economo. Electroencephalographic, evoked potential and autopsy data suggest that involvement of the cerebral cortex is more extensive than has been generally recognized. Serological tests and viral cultures failed to reveal the infectious agent but the presence of oligoclonal IgG banding in the cerebrospinal fluid in 3 of the patients during the acute phase of the illness would be in keeping with a viral aetiology. INTRODUCTION Accounts of febrile somnolent illnesses with residual apathy, ophthalmoplegia, chorea and weakness abound in the early literature. The Schlafkrankheit of 1580, Sydenham's febris comatosa of 1672-1675 in which hiccough was a prominent symptom, febre lethargica of 1695, coma somnolentium of 1780, Gerlier's vertige paralysante of 1887 and the dreaded Italian nona of 1889-1890, in which sleepiness, cranial nerve palsies and tremor occurred, are some examples of what may be a recur- ring plague caused by the same aetiological agent (Wilson, 1940; Sacks, 1982). Despite these historical forerunners, the sleeping sickness pandemic of 1916-1927 burst forth spontaneously in several different European cities unrecognized and then relentlessly spread around the world leaving an estimated half a million people dead or disabled. Constantin von Economo, however, relying in part on recollec- tions of his parents' descriptions of nona, was able to show that what appeared as a series of unrelated polymorphous outbreaks was in fact a disease caused by a single transmissible factor. -

Guidelines for Occupational Health Follow up of Communicable Diseases for Manager/Supervisors

Winnipeg Regional Health Authority Occupational and Environmental Safety & Health (OESH) Guidelines for Occupational Health Follow Up of Communicable Diseases For Manager/Supervisors Page | 1 2019.02.04 version 2 Winnipeg Regional Health Authority Occupational and Environmental Safety & Health (OESH) INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 WORKERS COMPENSATION BOARD (WCB) CLAIMS ........................................................................................................................... 5 ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANT ORGANISMS (AROS) ..................................................................................................................................... 6 BLOOD AND BODY FLUID EXPOSURES ............................................................................................................................................... 9 CIMEX LECTULARIUS (BED BUGS) .................................................................................................................................................... 10 CREUTZFELDT-JAKOB DISEASE (CJD) ................................................................................................................................................ 11 DIARRHEA (BACTERIAL, CLOSTRIDIUM DIFFICILE (C. DIFFICILE), VIRAL) ........................................................................................... 12 GROUP A STREPTOCOCCUS ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Hand-Foot-And-Mouth Disease Caused by Coxsackievirus A6 on the Rise

Hand-foot-and-mouth Disease Caused by Coxsackievirus A6 on the Rise Brooks David Kimmis, MD; Christopher Downing, MD; Stephen Tyring, MD, PhD CVA16 has traditionally been the primary strain caus- PRACTICE POINTS ing HFMD, CVA6 has become a major cause of HFMD • Coxsackievirus A6 is an increasingly more common outbreaks in the United States and worldwide in recent cause of hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD), years.6-12 Interestingly, CVA6 also has been found to be often with atypical presentation, more severe disease, associated with adult HFMD, which has increased in and association with HFMD in adults. incidence. The CVA6 strain was first identified in associa- • Coxsackievirus A6 has become a major cause of tion with the disease during HFMD outbreaks in Finland HFMD outbreak in the United States and worldwide. and Singapore in 2008,13,14 with similar strains detected in subsequent outbreaks in Taiwan, Japan, Spain, France, China, India, and the United States.12,15-25 Most cases took place in warmer months, with one winter outbreak in Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) is a viral illness caused Massachusetts in 2012.24 most commonly by coxsackievirus A16 (CVA16) and enterovirus 71 (EV71). The disease mainly affects pediatric populations younger Herein, we review the incidence of CVA6, as well as than 5 years and is characterized by lesions of the oral mucosa, its atypical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment to aid palms, and soles, lasting for 7 to 10 days. In recent years, CVA6 has dermatologists. Given the increasing incidence of HFMD become a major cause of HFMD outbreaks in the United States and caused by CVA6 and its often atypical presentation, it is worldwide. -

Coxsackievirus B

PRINCIPLE OF THE IFA PROCEDURE The MBL Bion COXSACKIEVIRUS B ANTIGEN SUBSTRATE SLIDES may be utilized in the indirect fluorescent antibody assay method first described by Weller COXSACKIEVIRUS B and Coons11 and further developed by Riggs, et al.12 The procedure is carried out in two basic reaction steps: ANTIGEN SUBSTRATE SLIDE Step 1 - Human serum is reacted with the antigen substrate. Antibodies, if present, will bind to the antigen forming stable antigen-antibody complexes. If no antibodies are present, the complexes will not be PRODUCT AVAILABILITY formed and serum components will be washed away. The following Coxsackievirus Group B Antigen Substrate Slides are available Step 2 - Fluorescein labeled antihuman IgG (or IgM) antibody is added to the individually from MBL Bion: reaction site which binds with the complexes formed in step one. This results in a positive reaction of bright apple-green fluorescence when Antigen Substrate Slide Code No. Code No. viewed with a properly equipped fluorescence microscope. If no complexes Coxsackievirus B (1-6) Screen CB-3312 CB-3306 are formed in step one, the fluorescein labeled antibody will be washed Number of Tests 12-Well 6-Well away, exhibiting a negative result. ( = Code Number) REAGENTS INTENDED USE MBL Bion COXSACKIEVIRUS B ANTIGEN SUBSTRATE SLIDES are The MBL Bion COXSACKIEVIRUS B ANTIGEN SUBSTRATE SLIDES may individually foil-wrapped slides of six or twelve wells with a mixture of be used as the antigenic substrate in indirect fluorescent antibody assays for Coxsackievirus B (1-6; NIH strains) infected and uninfected A549 cells fixed the qualitative and/or semi-quantitative determination of Coxsackievirus B onto each well. -

Clinical Syndromes/Conditions with Required Level Or Precautions

Clinical Syndromes/Conditions with Required Level or Precautions This resource is an excerpt from the Best Practices for Routine Practices and Additional Precautions (Appendix N) and was reformatted for ease of use. For more information please contact Public Health Ontario’s Infection Prevention and Control Department at [email protected] or visit www.publichealthontario.ca Clinical Syndromes/Conditions with Required Level or Precautions This is an excerpt from the Best Practices for Routine Practices and Additional Precautions (Appendix N) Table of Contents ABSCESS DECUBITUS ULCER HAEMORRHAGIC FEVERS NOROVIRUS SMALLPOX OPHTHALMIA ADENOVIRUS INFECTION DENGUE HEPATITIS, VIRAL STAPHYLOCOCCAL DISEASE NEONATORUM AIDS DERMATITIS HERPANGINA PARAINFLUENZA VIRUS STREPTOCOCCAL DISEASE AMOEBIASIS DIARRHEA HERPES SIMPLEX PARATYPHOID FEVER STRONGYLOIDIASIS ANTHRAX DIPHTHERIA HISTOPLASMOSIS PARVOVIRUS B19 SYPHILIS ANTIBIOTIC-RESISTANT EBOLA VIRUS HIV PEDICULOSIS TAPEWORM DISEASE ORGANISMS (AROs) ARTHROPOD-BORNE ECHINOCOCCOSIS HOOKWORM DISEASE PERTUSSIS TETANUS VIRAL INFECTIONS ASCARIASIS ECHOVIRUS DISEASE HUMAN HERPESVIRUS PINWORMS TINEA ASPERGILLOSIS EHRLICHIOSIS IMPETIGO PLAGUE TOXOPLASMOSIS INFECTIOUS BABESIOSIS ENCEPHALITIS PLEURODYNIA TOXIC SHOCK SYNDROME MONONUCLEOSIS ENTEROBACTERIACEAE- BLASTOMYCOSIS INFLUENZA PNEUMONIA TRENCHMOUTH RESISTANT BOTULISM ENTEROBIASIS KAWASAKI SYNDROME POLIOMYELITIS TRICHINOSIS PSEUDOMEMBRANOUS BRONCHITIS ENTEROCOLITIS LASSA FEVER TRICHOMONIASIS COLITIS -

HUMAN ADENOVIRUS Credibility of Association with Recreational Water: Strongly Associated

6 Viruses This chapter summarises the evidence for viral illnesses acquired through ingestion or inhalation of water or contact with water during water-based recreation. The organisms that will be described are: adenovirus; coxsackievirus; echovirus; hepatitis A virus; and hepatitis E virus. The following information for each organism is presented: general description, health aspects, evidence for association with recreational waters and a conclusion summarising the weight of evidence. © World Health Organization (WHO). Water Recreation and Disease. Plausibility of Associated Infections: Acute Effects, Sequelae and Mortality by Kathy Pond. Published by IWA Publishing, London, UK. ISBN: 1843390663 192 Water Recreation and Disease HUMAN ADENOVIRUS Credibility of association with recreational water: Strongly associated I Organism Pathogen Human adenovirus Taxonomy Adenoviruses belong to the family Adenoviridae. There are four genera: Mastadenovirus, Aviadenovirus, Atadenovirus and Siadenovirus. At present 51 antigenic types of human adenoviruses have been described. Human adenoviruses have been classified into six groups (A–F) on the basis of their physical, chemical and biological properties (WHO 2004). Reservoir Humans. Adenoviruses are ubiquitous in the environment where contamination by human faeces or sewage has occurred. Distribution Adenoviruses have worldwide distribution. Characteristics An important feature of the adenovirus is that it has a DNA rather than an RNA genome. Portions of this viral DNA persist in host cells after viral replication has stopped as either a circular extra chromosome or by integration into the host DNA (Hogg 2000). This persistence may be important in the pathogenesis of the known sequelae of adenoviral infection that include Swyer-James syndrome, permanent airways obstruction, bronchiectasis, bronchiolitis obliterans, and steroid-resistant asthma (Becroft 1971; Tan et al. -

Coxsackievirus A6-Induced Hand- Foot-And-Mouth Disease Mimicking Stevens-Johnson Syndrome in an Immunocompetent Adult

Infect Chemother. 2020 Dec;52(4):634-640 https://doi.org/10.3947/ic.2020.52.4.634 pISSN 2093-2340·eISSN 2092-6448 Case Report Coxsackievirus A6-induced Hand- Foot-and-Mouth Disease Mimicking Stevens-Johnson Syndrome in an Immunocompetent Adult Tae-Hoon No 1, Kyeong Min Jo 1, So Young Jung 2, Mi Ra Kim 3, Joo Yeon Kim 4, Chan Sun Park 5,*, and Sungmin Kym 6,* 1Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Internal Medicine, Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea 2Department of Dermatology, Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea 3Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital, Received: Mar 31, 2020 Busan, Korea Accepted: Jun 7, 2020 4Department of Pathology, Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea 5Division of Allergology, Department of Internal Medicine, Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital, Busan, Corresponding Authors: Korea Chan Sun Park, MD 6Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungnam National University Sejong Division of Allergology, Department of Internal Hospital, Sejong, Korea Medicine, Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital, 875 Haeun-daero, Haeundae-gu, Busan 48108, Korea. Tel: +82-51-797-2210 ABSTRACT Fax: +82-51-797-1341 E-mail: [email protected] Hand-foot-and-mouth disease, a highly contagious viral infection, occurs more common in children than in adults. However, there was a recent outbreak of Coxsackievirus A6- Sungmin Kym, MD, PhD induced infection with an atypical presentation among the adult population. Stevens– Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungnam National Johnson syndrome is a severe mucocutaneous disease characterized by extensive necrosis University Sejong Hospital, 20, Bodeum 7-ro, and detachment of the epidermis, and this condition is commonly caused by medications. -

STUDY of EXPRESSION of Αvβ6 INTEGRIN in POTENTIALLY MALIGNANT LESIONS – an IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY STUDY

STUDY OF EXPRESSION OF αvβ6 INTEGRIN IN POTENTIALLY MALIGNANT LESIONS – AN IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY STUDY Dissertation submitted to THE TAMILNADU Dr. M.G.R. MEDICAL UNIVERSITY In partial fulfilment for the Degree of MASTER OF DENTAL SURGERY BRANCH VI ORAL PATHOLOGY AND MICROBIOLOGY MAY 2018 Acknowledgement ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to take this opportunity to express my gratitude to everyone who has helped me through this journey. I would like to start with my very respected and benevolent teacher, Dr. Ranganathan K, Professor and Head, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Ragas Dental College and Hospital. I consider myself blessed to have the opportunity to study under his guidance. He has always been a source of inspiration to excel in academics and career. I would offer my obeisance unto him for having taken interest in my study and instilling knowledge. Thank you so much sir. I owe enormous debt of gratitude to my professor Dr. Uma Devi K Rao for helping me in completing my thesis. She always has been a pillar of support and encouragement all throughout my post graduate life. She was approachable for any help and always made me feel at home by her caring nature. I want to take this opportunity to acknowledge and thank her for the help and support. Thank you mam. I express my profound gratitude to my revered guide Dr. Elizabeth Joshua, Professor for her encouragement, advice and guidance which helped me complete my dissertation. She has been an integral part of my post graduation and I want to take this opportunity to acknowledge and thank her for her help and support.