Demonstration of “Substantial Research Activity” to Acquire Consultative Status Under the Antarctic Treaty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Landscapes of Exploration' Education Pack

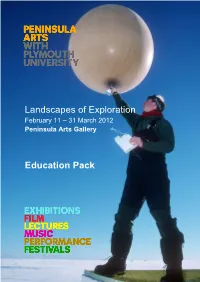

Landscapes of Exploration February 11 – 31 March 2012 Peninsula Arts Gallery Education Pack Cover image courtesy of British Antarctic Survey Cover image: Launch of a radiosonde meteorological balloon by a scientist/meteorologist at Halley Research Station. Atmospheric scientists at Rothera and Halley Research Stations collect data about the atmosphere above Antarctica this is done by launching radiosonde meteorological balloons which have small sensors and a transmitter attached to them. The balloons are filled with helium and so rise high into the Antarctic atmosphere sampling the air and transmitting the data back to the station far below. A radiosonde meteorological balloon holds an impressive 2,000 litres of helium, giving it enough lift to climb for up to two hours. Helium is lighter than air and so causes the balloon to rise rapidly through the atmosphere, while the instruments beneath it sample all the required data and transmit the information back to the surface. - Permissions for information on radiosonde meteorological balloons kindly provided by British Antarctic Survey. For a full activity sheet on how scientists collect data from the air in Antarctica please visit the Discovering Antarctica website www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk and select resources www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk has been developed jointly by the Royal Geographical Society, with IBG0 and the British Antarctic Survey, with funding from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) supports geography in universities and schools, through expeditions and fieldwork and with the public and policy makers. Full details about the Society’s work, and how you can become a member, is available on www.rgs.org All activities in this handbook that are from www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk will be clearly identified. -

The Netherlands Polar Programme and the Dirck Gerritsz Laboratory

Earth and Life Sciences (ALW) Netherlands Polar Programme: the Dirck Gerritsz Laboratory The Netherlands Polar Programme and the Dirck Gerritsz Laboratory The Netherlands Polar Programme (NPP) is a research programme that funds Dutch scientific research into and at the polar regions. The assessment of the research proposals together with the realisation and coordination of the NPP has been assigned by the financiers to NWO, and NWO’s Division for the Earth and Life Sciences has assumed responsibility for this. The NPP has set up the Dirck Gerritsz Laboratory at the British Antarctic Survey’s Rothera Research Station in Antarctica. Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research Definition of the problem The polar regions are very sensitive to climate change: they form the heart of the climate system. Climate change in the polar regions has major physical, ecological, social and economic consequences that extend far beyond their boundaries. Due to the worldwide atmospheric and oceanic circulation systems, changes in the polar regions are felt throughout the world. A good understanding of these changes is important for the Netherlands; for example, as a low-lying country the Netherlands is vulnerable to sea level rises. Dirck Gerritsz Laboratory at Rothera Research Station NWO has set up the Dutch mobile research facility at the British research station Rothera on the Antarctic Peninsula. With this laboratory the Netherlands has become a fully fledged research partner within international polar research. Antarctica is a unique research environment where the consequences of climate change can be clearly measured without the disruptive influences of people. NWO is collaborating on Antarctica with the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). -

BAS Science Summaries 2018-2019 Antarctic Field Season

BAS Science Summaries 2018-2019 Antarctic field season BAS Science Summaries 2018-2019 Antarctic field season Introduction This booklet contains the project summaries of field, station and ship-based science that the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) is supporting during the forthcoming 2018/19 Antarctic field season. I think it demonstrates once again the breadth and scale of the science that BAS undertakes and supports. For more detailed information about individual projects please contact the Principal Investigators. There is no doubt that 2018/19 is another challenging field season, and it’s one in which the key focus is on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) and how this has changed in the past, and may change in the future. Three projects, all logistically big in their scale, are BEAMISH, Thwaites and WACSWAIN. They will advance our understanding of the fragility and complexity of the WAIS and how the ice sheets are responding to environmental change, and contributing to global sea-level rise. Please note that only the PIs and field personnel have been listed in this document. PIs appear in capitals and in brackets if they are not present on site, and Field Guides are indicated with an asterisk. Non-BAS personnel are shown in blue. A full list of non-BAS personnel and their affiliated organisations is shown in the Appendix. My thanks to the authors for their contributions, to MAGIC for the field sites map, and to Elaine Fitzcharles and Ali Massey for collating all the material together. Thanks also to members of the Communications Team for the editing and production of this handy summary. -

Public Information Leaflet HISTORY.Indd

British Antarctic Survey History The United Kingdom has a long and distinguished record of scientific exploration in Antarctica. Before the creation of the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), there were many surveying and scientific expeditions that laid the foundations for modern polar science. These ranged from Captain Cook’s naval voyages of the 18th century, to the famous expeditions led by Scott and Shackleton, to a secret wartime operation to secure British interests in Antarctica. Today, BAS is a world leader in polar science, maintaining the UK’s long history of Antarctic discovery and scientific endeavour. The early years Britain’s interests in Antarctica started with the first circumnavigation of the Antarctic continent by Captain James Cook during his voyage of 1772-75. Cook sailed his two ships, HMS Resolution and HMS Adventure, into the pack ice reaching as far as 71°10' south and crossing the Antarctic Circle for the first time. He discovered South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands although he did not set eyes on the Antarctic continent itself. His reports of fur seals led many sealers from Britain and the United States to head to the Antarctic to begin a long and unsustainable exploitation of the Southern Ocean. Image: Unloading cargo for the construction of ‘Base A’ on Goudier Island, Antarctic Peninsula (1944). During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, interest in Antarctica was largely focused on the exploitation of its surrounding waters by sealers and whalers. The discovery of the South Shetland Islands is attributed to Captain William Smith who was blown off course when sailing around Cape Horn in 1819. -

Tanu Jindal Director and Professor Amity Institute of Environmental

Anthropogenic Activities and Environmental contamination in Antarctic regions Professor (Dr.) Tanu Jindal Director Amity Institute for Environmental Toxicology, Safety and Management Amity Institute of Environmental Science & Amity center for Antarctic Research and studies Amity University Uttar Pradesh, Noida, Uttar Pradesh Overview • Antarctica is often thought of as a pristine land untouched by human disturbance. Unfortunately this is no longer the case. For more than 100 years people have been travelling to Antarctica and in that short time most parts have been visited • Over the years since the Antarctic Treaty came into force, greater environmental awareness has led to increasing regulation by the Antarctic Treaty System. • It is necessary to monitor the persistent contaminants i.e. VOCs, PCBs, PAHs, dioxins, pesticides, Heavy metals as well as microbial contamination by non-native species through Human activities to check further contamination. • Environmental studies have been undertaken in the area around Indian Station “Maitri” to establish base line parameters on several environmental parameters by NEERI, NCAOR and SRIIR etc but the data is scarce in newly established Bharti Station Antarctic Pollution Issues • Antarctica is a continent devoid of permanent human settlement which is now being largely affected by various anthropogenic activities • In 1959 Antarctica was established as an international center for science and research, which led international teams to conduct research on the continent. • Further research will lead -

Long-Term Survival of Human Faecal Microorganisms on the Antarctic Peninsula KEVIN A

Antarctic Science 16 (3): 293–297 (2004) © Antarctic Science Ltd Printed in the UK DOI: 10.1017/S095410200400210X Long-term survival of human faecal microorganisms on the Antarctic Peninsula KEVIN A. HUGHES*1 and SIMON J. NOBBS2 1British Antarctic Survey, NERC, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK 2Department of Microbiology, Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust, Derriford Hospital, Plymouth PL6 8DH, UK * Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: Human faecal waste has been discarded at inland Antarctic sites for over 100 years, but little is known about the long-term survival of faecal microorganisms in the Antarctic terrestrial environment or the environmental impact. This study identified viable faecal microorganisms in 30–40 year old human faeces sampled from the waste dump at Fossil Bluff Field Station, Alexander Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Viable aerobic and anaerobic bacteria were predominantly spore-forming varieties (Bacillus and Clostridium spp.). Faecal coliform bacteria were not detected, indicating that they are less able to survive Antarctic environmental conditions than spore-forming bacteria. In recent years, regional warming around the Antarctic Peninsula has caused a decrease in permanent snow cover around nunataks and coastal regions. As a result, previously buried toilet pits, depots and food dumps are now melting out and Antarctic Treaty Parties face the legacy of waste dumped in the Antarctic terrestrial environment by earlier expeditions. Previous faecal waste disposal on land may now start to produce detectable environmental pollution as well as potential health and scientific problems. Received 18 August 2003, accepted 26 April 2004 Key words: Antarctica, climate change, Environmental Protocol, faecal bacteria, faecal coliforms, freezing Introduction emptied into a nearby crevasse. -

And Better Science in Antarctica Through Increased Logistical Effectiveness

MORE AND BETTER SCIENCE IN ANTARCTICA THROUGH INCREASED LOGISTICAL EFFECTIVENESS Report of the U.S. Antarctic Program Blue Ribbon Panel Washington, D.C. July 2012 This report of the U.S. Antarctic Program Blue Ribbon Panel, More and Better Science in Antarctica Through Increased Logistical Effectiveness, was completed at the request of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and the National Science Foundation. Copies may be obtained from David Friscic at [email protected] (phone: 703-292-8030). An electronic copy of the report may be downloaded from http://www.nsf.gov/od/ opp/usap_special_review/usap_brp/rpt/index.jsp. Cover art by Zina Deretsky. MORE AND BETTER SCIENCE IN AntarctICA THROUGH INCREASED LOGISTICAL EFFECTIVENESS REport OF THE U.S. AntarctIC PROGRAM BLUE RIBBON PANEL AT THE REQUEST OF THE WHITE HOUSE OFFICE OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY POLICY AND THE NatIONAL SCIENCE FoundatION WASHINGTON, D.C. JULY 2012 U.S. AntarctIC PROGRAM BLUE RIBBON PANEL WASHINGTON, D.C. July 23, 2012 Dr. John P. Holdren Dr. Subra Suresh Assistant to the President for Science and Technology Director & Director, Office of Science and Technology Policy National Science Foundation Executive Office of the President of the United States 4201 Wilson Boulevard Washington, DC 20305 Arlington, VA 22230 Dear Dr. Holdren and Dr. Suresh: The members of the U.S. Antarctic Program Blue Ribbon Panel are pleased to submit herewith our final report entitled More and Better Science in Antarctica through Increased Logistical Effectiveness. Not only is the U.S. logistics system supporting our nation’s activities in Antarctica and the Southern Ocean the essential enabler for our presence and scientific accomplish- ments in that region, it is also the dominant consumer of the funds allocated to those endeavors. -

2571 Country Code

2571 Country Code. CountryCode.org is your complete guide to call anywhere in the world. The calling chart above will help you find the dialing codes you need to make long distance phone calls to friends, family, and business partners around the globe. Simply find and click the country you wish to call. You'll find instructions on how to call that country using its country code, as well as other helpful information like area codes, ISO country codes, and the kinds of electrical outlets and phone jacks found in that part of the world. Making a phone call has never been easier with CountryCode.org. The 2-letter codes shown below are supplied by the ISO ( International Organization for Standardization). It bases its list of country names and abbreviations on the list of names published by the United Nations. The UN also uses 3-letter codes, and numerical codes to identify nations, and those are shown below. International Dialing Codes for making overseas phone calls are also listed below. Note: If the columns don't align correctly, please increase the font size in your browser. COUNTRY A2 (ISO) A3 (UN) NUM (UN) DIALING CODE Afghanistan AF AFG 4 93 Albania AL ALB 8 355 Algeria DZ DZA 12 213 American Samoa AS ASM 16 1-684 Andorra AD AND 20 376 Angola AO AGO 24 244 Anguilla AI AIA 660 1-264 Antarctica AQ ATA 10 672 Antigua and Barbuda AG ATG 28 1-268 Argentina AR ARG 32 54 Armenia AM ARM 51 374 Aruba AW ABW 533 297 Australia AU AUS 36 61 Austria AT AUT 40 43 Azerbaijan AZ AZE 31 994 Bahamas BS BHS 44 1-242 Bahrain BH BHR 48 973 Bangladesh BD -

Surviving on the Edge: Medicine in Antarctica

Surviving on the Edge: Medicine in Antarctica ALEXANDER KUMAR DC8 Winter Crew Station Doctor and European Space Agency Research, Concordia Station, Antarctica SOPHIE DUONG Harris Academy, London Living at Antarctica’s Concordia Station, buried deep within the world’s worst winter, this year’s winter crew station doctor has time to appreciate where Antarctic medicine has come in the past 100 years. In all the world there is no desolation more age of exploration. In times of health, expedition complete than the polar night. It is a return to the doctors conducted (and still do) natural science Ice Age – no warmth, no life, no movement. Only those who have experienced it can fully appreciate research. what it means to be without the sun day after day We have had many past lessons to build our and week after week. Few men unaccustomed to it foundation of medical knowledge upon. Sir can fight off its effects altogether and it has driven Douglas Mawson’s 1911–14 Australasian some men mad. Sir Ernest Shackleton Antarctic Expedition pioneered the use of wireless communications in Antarctica, he quest for the South Pole has forged enabling growth in the field of telemedicine. a unique celebrated, tragic and heroic Large advances have been made in the past legacy. Antarctic medicine stands on 100 years in attempts to provide a means for Tits own plinth of risk, tragedy and medical self-sufficiency for the lone doctors triumph, much like the physicians it entertains littered among the increasing number of each winter. international crews, locking themselves into the Celebrating not only Antarctic medical staff, brutal and unforgiving Antarctic winter, where we bring to light other unsung heroes within a simple mistake or oversight can cost lives. -

IDS Activity Report 2013

International Doris Service Activity Report 2013 The International DORIS Service 2013 Annual Report R. Biancale (1), H. Capdeville (2), P. Ferrage (1), B. Garayt (3), S. Kuzin (4), F.G. Lemoine (5), B. Luzum (6), G. Moreaux (2), C.E. Noll (5), M. Otten (7), J.C. Ries (8), J. Saunier (3), L. Soudarin (2), P. Stepanek (9), P. Willis (10, 11). (1) Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales, 18 Avenue Edouard Belin, 31401 Toulouse Cedex 9, FRANCE (2) Collecte Localisation Satellites, 8-10, rue Hermès, Parc Technologique du Canal, 31520 Ramonville Saint- Agne, FRANCE (3) Institut National de l’Information Géographique et Forestière, Service de la Géodésie et du Nivellement, 73, avenue de Paris, 94165 Saint-Mandé Cedex, France (4) Institute of Astronomy, Russian Academy of Sciences, 48, Pyatnitskaya St., Moscow 119017, RUSSIA (5) NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland 20771, USA (6) US Naval Observatory, 3450 Massachusetts Ave NW, Washington DC 20392 5420, USA (7) European Space Agency, European Space Operation Centre, Robert-Bosch-Strasse 5, 64293 Darmstadt, GERMANY (8) Center for Space Research, University of Texas, R1000, Austin, TX 78712, USA (9) Geodesy Observatory Pecný, Research Institute of Geodesy, Topography and Cartography, Ondrejov 244, 25165 Prague-East, CZECH REPUBLIC (10) Institut Géographique National, Direction Technique, 73, avenue de Paris, 94165 Saint-Mandé, FRANCE (11) Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, UFR STEP / GSP Bat Lamarck Case 7011, 75013 Paris Cedex 13, France Preface In this volume, the International DORIS Service documents the work of the IDS components between January 2013 and December 2013. The individual reports were contributed by IDS groups in the international geodetic community who make up the permanent components of IDS. -

Snow Algae Communities in Antarctica: Metabolic and Taxonomic Composition

Research Snow algae communities in Antarctica: metabolic and taxonomic composition Matthew P. Davey1 , Louisa Norman1 , Peter Sterk2 , Maria Huete-Ortega1 , Freddy Bunbury1, Bradford Kin Wai Loh1 , Sian Stockton1, Lloyd S. Peck3, Peter Convey3 , Kevin K. Newsham3 and Alison G. Smith1 1Department of Plant Sciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB2 3EA, UK; 2Cambridge Institute for Medical Research, University of Cambridge, Wellcome Trust MRC Building, Hills Road, Cambridge, CB2 0QQ, UK; 3British Antarctic Survey, NERC, Madingley Road, Cambridge, CB3 0ET, UK Summary Author for correspondence: Snow algae are found in snowfields across cold regions of the planet, forming highly visible Matthew P. Davey red and green patches below and on the snow surface. In Antarctica, they contribute signifi- Tel: +44 (0)1223 333943 cantly to terrestrial net primary productivity due to the paucity of land plants, but our knowl- Email: [email protected] edge of these communities is limited. Here we provide the first description of the metabolic Received: 8 November 2018 and species diversity of green and red snow algae communities from four locations in Ryder Accepted: 8 January 2019 Bay (Adelaide Island, 68°S), Antarctic Peninsula. During the 2015 austral summer season, we collected samples to measure the metabolic New Phytologist (2019) composition of snow algae communities and determined the species composition of these doi: 10.1111/nph.15701 communities using metabarcoding. Green communities were protein-rich, had a high chlorophyll content and contained many Key words: Antarctica, bacteria, community metabolites associated with nitrogen and amino acid metabolism. Red communities had a composition, cryophilic, fungi, metabarcod- higher carotenoid content and contained more metabolites associated with carbohydrate and ing, metabolomics, snow algae. -

Microplastics in Marine Sediments Near Rothera Research Station, Antarctica

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk Faculty of Science and Engineering School of Biological and Marine Sciences 2018-08 Microplastics in marine sediments near Rothera Research Station, Antarctica Reed, S http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/11865 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.05.068 Marine Pollution Bulletin Elsevier All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. Disclaimer: This is a pre--‐publication version. Readers are advised to refer to the final published version. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X18303977?via%3Dihub Microplastics in marine sediments near Rothera Research Station, Antarctica Sarah Reed1, 2, Marlon Clark1,3, Richard Thompson3 and Kevin A. Hughes1* 1 British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK 2 Scottish Association for Marine Science, Scottish Marine Institute, Oban, Argyll, PA37 1QA 3University of Plymouth, Davy Building, Drake Circus, Plymouth, Devon, PL4 8AA * corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]; Tel: +44 (0)1223221616 1 Abstract Antarctica and surrounding waters are often considered pristine, but may be subject to local pollution from tourism, fishing and governmental research programme activities. In particular, the quantification of microplastic pollution within the Antarctic Treaty area (south of latitude 60oS) has received little attention. We examined microplastic particle concentrations in sediment samples from 20 locations up to 7 km from Rothera Research Station.