Meta-Analysis of Survey Data to Assess Trends of Prairie Butterflies in Minnesota, USA During 1979–2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identification of Insect-Plant Pollination Networks for a Midwest Installation: Fort Mccoy, WI 5B

1 - 16 - ERDC TN ERDC Center for the Advancement of Sustainability Innovations (CASI) Identification of Insect-Plant Pollination Networks for a Midwest Installation Fort McCoy, WI Irene E. MacAllister, Jinelle H. Sperry, and Pamela Bailey April 2016 Results of an insect pollinators bipartite mutualistic network analysis. Construction Engineering Construction Laboratory Research Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. The U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC) solves the nation’s toughest engineering and environmental challenges. ERDC develops innovative solutions in civil and military engineering, geospatial sciences, water resources, and environmental sciences for the Army, the Department of Defense, civilian agencies, and our nation’s public good. Find out more at www.erdc.usace.army.mil. To search for other technical reports published by ERDC, visit the ERDC online library at http://acwc.sdp.sirsi.net/client/default. Center for the Advancement of ERDC TN-16-1 Sustainability Innovations (CASI) April 2016 Identification of Insect-Plant Pollination Networks for a Midwest Installation Fort McCoy, WI Irene E. MacAllister and Jinelle H. Sperry U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC) Construction Engineering Research Laboratory (CERL) 2902 Newmark Dr. Champaign, IL 61822 Pamela Bailey U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center Environmental Laboratory (EL) 3909 Halls Ferry Road Vicksburg, MS 39180-6199 Final Report Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Prepared for U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center Vicksburg, MS 39180-6199 Under Center for the Advancement of Sustainability Innovations (CASI) Program Monitored by U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center Construction Engineering Research Laboratory (ERDC-CERL) 2902 Newmark Drive Champaign, IL 61822 ERDC TN-16-1 ii Abstract Pollinating insects and pollinator dependent plants are critical compo- nents of functioning ecosystems yet, for many U.S. -

Natural History and Conservation Genetics of the Federally Endangered Mitchell’S Satyr Butterfly, Neonympha Mitchellii Mitchellii

NATURAL HISTORY AND CONSERVATION GENETICS OF THE FEDERALLY ENDANGERED MITCHELL’S SATYR BUTTERFLY, NEONYMPHA MITCHELLII MITCHELLII By Christopher Alan Hamm A DISSRETATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Entomology Ecology, Evolutionary Biology and Behavior – Dual Major 2012 ABSTRACT NATURAL HISTORY AND CONSERVATION GENETICS OF THE FEDERALLY ENDANGERED MITCHELL’S SATYR BUTTERFLY, NEONYMPHA MITCHELLII MITCHELLII By Christopher Alan Hamm The Mitchell’s satyr butterfly, Neonympha mitchellii mitchellii, is a federally endangered species with protected populations found in Michigan, Indiana, and wherever else populations may be discovered. The conservation status of the Mitchell’s satyr began to be called into question when populations of a phenotypically similar butterfly were discovered in the eastern United States. It is unclear if these recently discovered populations are N. m. mitchellii and thus warrant protection. In order to clarify the conservation status of the Mitchell’s satyr I first acquired sample sizes large enough for population genetic analysis I developed a method of non- lethal sampling that has no detectable effect on the survival of the butterfly. I then traveled to all regions in which N. mitchellii is known to be extant and collected genetic samples. Using a variety of population genetic techniques I demonstrated that the federally protected populations in Michigan and Indiana are genetically distinct from the recently discovered populations in the southern US. I also detected the presence of the reproductive endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia, and surveyed addition Lepidoptera of conservation concern. This survey revealed that Wolbachia is a real concern for conservation managers and should be addressed in management plans. -

Working List of Prairie Restricted (Specialist) Insects in Wisconsin (11/26/2015)

Working List of Prairie Restricted (Specialist) Insects in Wisconsin (11/26/2015) By Richard Henderson Research Ecologist, WI DNR Bureau of Science Services Summary This is a preliminary list of insects that are either well known, or likely, to be closely associated with Wisconsin’s original native prairie. These species are mostly dependent upon remnants of original prairie, or plantings/restorations of prairie where their hosts have been re-established (see discussion below), and thus are rarely found outside of these settings. The list also includes some species tied to native ecosystems that grade into prairie, such as savannas, sand barrens, fens, sedge meadow, and shallow marsh. The list is annotated with known host(s) of each insect, and the likelihood of its presence in the state (see key at end of list for specifics). This working list is a byproduct of a prairie invertebrate study I coordinated from1995-2005 that covered 6 Midwestern states and included 14 cooperators. The project surveyed insects on prairie remnants and investigated the effects of fire on those insects. It was funded in part by a series of grants from the US Fish and Wildlife Service. So far, the list has 475 species. However, this is a partial list at best, representing approximately only ¼ of the prairie-specialist insects likely present in the region (see discussion below). Significant input to this list is needed, as there are major taxa groups missing or greatly under represented. Such absence is not necessarily due to few or no prairie-specialists in those groups, but due more to lack of knowledge about life histories (at least published knowledge), unsettled taxonomy, and lack of taxonomic specialists currently working in those groups. -

Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Surveys and Stewardship Activities, 2013

Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Surveys and Stewardship Activities, 2013 Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Colin Murray Report No. 2014-01 Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Box 24, 200 Saulteaux Crescent Winnipeg, Manitoba R3J 3W3 www.manitoba.ca/conservation/cdc Recommended Citation: Murray, C. 2014. Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Surveys and Stewardship Activities, 2013. Report No. 2014-01. Manitoba Conservation Data Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba. v+41 pp. Images: Unless otherwise noted, all images are ©Manitoba Conservation Data Centre. Cover image: View of the Assiniboine River and Beaver Creek valleys looking south from a top the valley plateau. Inset is a White Flower Moth (Schinia bimatris) at rest. Photographed at Spruce Woods Provincial Park. Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Surveys and Stewardship Activities, 2013 By Colin Murray Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Wildlife Branch Manitoba Conservation and Water Stewardship Winnipeg, Manitoba Executive Summary In 2013, the Manitoba Conservation Data Center (MBCDC) added nearly 1,240 new occurrences to its Biodiversity Geospatial Database. This represents thousands of species at risk (SAR) observations including 27 plant and 51 animal species. Observations were gathered by MBCDC staff and also submitted to the MBCDC by individuals and other organisations. This information will further enhance our understanding of biodiversity in Manitoba and guide research, development, and educational efforts. This year MBCDC field surveys targeted 21 species which are listed under the federal Species at Risk Act, assessed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), and listed under Manitoba’s Endangered Species and Ecosystems Act, and especially occurring in the mixed-grass prairie and sandhill areas of southwestern Manitoba. -

A Fish Habitat Partnership

A Fish Habitat Partnership Strategic Plan for Fish Habitat Conservation in Midwest Glacial Lakes Engbretson Underwater Photography September 30, 2009 This page intentionally left blank. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 I. BACKGROUND 7 II. VALUES OF GLACIAL LAKES 8 III. OVERVIEW OF IMPACTS TO GLACIAL LAKES 9 IV. AN ECOREGIONAL APPROACH 14 V. MULTIPLE INTERESTS WITH COMMON GOALS 23 VI. INVASIVES SPECIES, CLIMATE CHANGE 23 VII. CHALLENGES 25 VIII. INTERIM OBJECTIVES AND TARGETS 26 IX. INTERIM PRIORITY WATERSHEDS 29 LITERATURE CITED 30 APPENDICES I Steering Committee, Contributing Partners and Working Groups 33 II Fish Habitat Conservation Strategies Grouped By Themes 34 III Species of Greatest Conservation Need By Level III Ecoregions 36 Contact Information: Pat Rivers, Midwest Glacial Lakes Project Manager 1601 Minnesota Drive Brainerd, MN 56401 Telephone 218-327-4306 [email protected] www.midwestglaciallakes.org 3 Executive Summary OUR MISSION The mission of the Midwest Glacial Lakes Partnership is to work together to protect, rehabilitate, and enhance sustainable fish habitats in glacial lakes of the Midwest for the use and enjoyment of current and future generations. Glacial lakes (lakes formed by glacial activity) are a common feature on the midwestern landscape. From small, productive potholes to the large windswept walleye “factories”, glacial lakes are an integral part of the communities within which they are found and taken collectively are a resource of national importance. Despite this value, lakes are commonly treated more as a commodity rather than a natural resource susceptible to degradation. Often viewed apart from the landscape within which they occupy, human activities on land—and in water—have compromised many of these systems. -

Plant Inventory at Missouri National Recreational River

Inventory of Butterflies at Fort Union Trading Post and Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Sites in 2004 --<o>-- Final Report Submitted by: Ronald Alan Royer, Ph.D. Burlington, North Dakota 58722 Submitted to: Northern Great Plains Inventory & Monitoring Coordinator National Park Service Mount Rushmore National Memorial Keystone, South Dakota 57751 October 1, 2004 Executive Summary This document reports inventory of butterflies at Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site (NHS) and Fort Union Trading Post NHS, both administered by the National Park Service in the state of North Dakota. Field work consisted of strategically timed visits throughout Summer 2004. The inventory employed “checklist” counting based on the author's experience with habitat for the various species expected from each site. This report is written in two separate parts, one for each site. Each part contains an annotated species list for that site. For possible later GIS use, noteworthy species encounters are reported by UTM coordinates, all of which are provided conveniently in a table within the report narrative for each site. An annotated listing is also included for each species at each site. Each of these provides a brief description of typical habitat, principal larval host(s), and information on adult phenology. This information is followed by abbreviated citations for published works in which more detailed information may be located. Recommendations are then made for each site on the basis of endemism, prairie butterfly conservation and -

List of Insect Species Which May Be Tallgrass Prairie Specialists

Conservation Biology Research Grants Program Division of Ecological Services © Minnesota Department of Natural Resources List of Insect Species which May Be Tallgrass Prairie Specialists Final Report to the USFWS Cooperating Agencies July 1, 1996 Catherine Reed Entomology Department 219 Hodson Hall University of Minnesota St. Paul MN 55108 phone 612-624-3423 e-mail [email protected] This study was funded in part by a grant from the USFWS and Cooperating Agencies. Table of Contents Summary.................................................................................................. 2 Introduction...............................................................................................2 Methods.....................................................................................................3 Results.....................................................................................................4 Discussion and Evaluation................................................................................................26 Recommendations....................................................................................29 References..............................................................................................33 Summary Approximately 728 insect and allied species and subspecies were considered to be possible prairie specialists based on any of the following criteria: defined as prairie specialists by authorities; required prairie plant species or genera as their adult or larval food; were obligate predators, parasites -

Amorpha Canescens Pursh Leadplant

leadplant, Page 1 Amorpha canescens Pursh leadplant State Distribution Best Survey Period Photo by Susan R. Crispin Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Status: State special concern the Mississippi valley through Arkansas to Texas and in the western Great Plains from Montana south Global and state rank: G5/S3 through Wyoming and Colorado to New Mexico. It is considered rare in Arkansas and Wyoming and is known Other common names: lead-plant, downy indigobush only from historical records in Montana and Ontario (NatureServe 2006). Family: Fabaceae (pea family); also known as the Leguminosae. State distribution: Of Michigan’s more than 50 occurrences of this prairie species, the vast majority of Synonym: Amorpha brachycarpa E.J. Palmer sites are concentrated in southwest Lower Michigan, with Kalamazoo, St. Joseph, and Cass counties alone Taxonomy: The Fabaceae is divided into three well accounting for more than 40 of these records. Single known and distinct subfamilies, the Mimosoideae, outlying occurrences have been documented in the Caesalpinioideae, and Papilionoideae, which are last two decades from prairie remnants in Oakland and frequently recognized at the rank of family (the Livingston counties in southeast Michigan. Mimosaceae, Caesalpiniaceae, and Papilionaceae or Fabaceae, respectively). Of the three subfamilies, Recognition: Leadplant is an erect, simple to sparsely Amorpha is placed within the Papilionoideae (Voss branching shrub ranging up to ca. 1 m in height, 1985). Sparsely hairy plants of leadplant with greener characterized by its pale to grayish color derived from leaves have been segregated variously as A. canescens a close pubescence of whitish hairs that cover the plant var. -

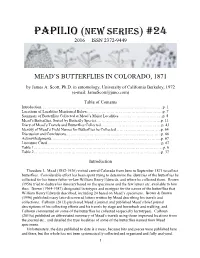

Papilio (New Series) #24 2016 Issn 2372-9449

PAPILIO (NEW SERIES) #24 2016 ISSN 2372-9449 MEAD’S BUTTERFLIES IN COLORADO, 1871 by James A. Scott, Ph.D. in entomology, University of California Berkeley, 1972 (e-mail: [email protected]) Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………..……….……………….p. 1 Locations of Localities Mentioned Below…………………………………..……..……….p. 7 Summary of Butterflies Collected at Mead’s Major Localities………………….…..……..p. 8 Mead’s Butterflies, Sorted by Butterfly Species…………………………………………..p. 11 Diary of Mead’s Travels and Butterflies Collected……………………………….……….p. 43 Identity of Mead’s Field Names for Butterflies he Collected……………………….…….p. 64 Discussion and Conclusions………………………………………………….……………p. 66 Acknowledgments………………………………………………………….……………...p. 67 Literature Cited……………………………………………………………….………...….p. 67 Table 1………………………………………………………………………….………..….p. 6 Table 2……………………………………………………………………………………..p. 37 Introduction Theodore L. Mead (1852-1936) visited central Colorado from June to September 1871 to collect butterflies. Considerable effort has been spent trying to determine the identities of the butterflies he collected for his future father-in-law William Henry Edwards, and where he collected them. Brown (1956) tried to deduce his itinerary based on the specimens and the few letters etc. available to him then. Brown (1964-1987) designated lectotypes and neotypes for the names of the butterflies that William Henry Edwards described, including 24 based on Mead’s specimens. Brown & Brown (1996) published many later-discovered letters written by Mead describing his travels and collections. Calhoun (2013) purchased Mead’s journal and published Mead’s brief journal descriptions of his collecting efforts and his travels by stage and horseback and walking, and Calhoun commented on some of the butterflies he collected (especially lectotypes). Calhoun (2015a) published an abbreviated summary of Mead’s travels using those improved locations from the journal etc., and detailed the type localities of some of the butterflies named from Mead specimens. -

NOVITATES PUBLISHED by the AMERICAN MUSEUM of NATURAL HISTORY CITY of NEW YORK MAY 6, 1953 NUMBER 1626 the SUBSPECIES of OENEIS ALBERTA (LEPIDOPTERA, SATYRIDAE) by F

AVMER]ICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CITY OF NEW YORK MAY 6, 1953 NUMBER 1626 THE SUBSPECIES OF OENEIS ALBERTA (LEPIDOPTERA, SATYRIDAE) By F. MARTIN BROWN' For some years Oeneis alberta oslari Skinner has been a very rare butterfly in collections. In early June, 1951, I had the good for- tune to find it rather plentiful in South Park, Park County, Colo- rado. The circumstances leading to its rediscovery and some notes on its habitat have been published (1952, Ent. News, vol. 63, pp. 119-123). This recently captured series of oslari affords the first opportunity to compare critically the three named entities that compose the species. The first-named of these, alberta Elwes and Edwards, is found on the prairies of Alberta and Saskatche- wan and is the best known of the three. During the following year Strecker described daura from the mountains of Arizona. This subspecies remained "lost" until D. K. Duncan, then of Globe, Arizona, recovered it in the vicinity of McNary in the White Mountains of Arizona during the early thirties. Oslari was last described. So far as I know the only true oslari in museum col- lections are the two pairs sent by Oslar to Skinner. All others that I have seen have been abberant Oeneis uhleri uhleri Reakirt. The data of Oslar's specimens misled collectors; they were taken in September, 1909. With almost 100 specimens representing the species before me it is quite evident that daura is distinctive a large, pale tawny creature. The other two subspecies are much alike, smaller and grayer than daura. -

MOTHS and BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed Distributional Information Has Been J.D

MOTHS AND BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed distributional information has been J.D. Lafontaine published for only a few groups of Lepidoptera in western Biological Resources Program, Agriculture and Agri-food Canada. Scott (1986) gives good distribution maps for Canada butterflies in North America but these are generalized shade Central Experimental Farm Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 maps that give no detail within the Montane Cordillera Ecozone. A series of memoirs on the Inchworms (family and Geometridae) of Canada by McGuffin (1967, 1972, 1977, 1981, 1987) and Bolte (1990) cover about 3/4 of the Canadian J.T. Troubridge fauna and include dot maps for most species. A long term project on the “Forest Lepidoptera of Canada” resulted in a Pacific Agri-Food Research Centre (Agassiz) four volume series on Lepidoptera that feed on trees in Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Canada and these also give dot maps for most species Box 1000, Agassiz, B.C. V0M 1A0 (McGugan, 1958; Prentice, 1962, 1963, 1965). Dot maps for three groups of Cutworm Moths (Family Noctuidae): the subfamily Plusiinae (Lafontaine and Poole, 1991), the subfamilies Cuculliinae and Psaphidinae (Poole, 1995), and ABSTRACT the tribe Noctuini (subfamily Noctuinae) (Lafontaine, 1998) have also been published. Most fascicles in The Moths of The Montane Cordillera Ecozone of British Columbia America North of Mexico series (e.g. Ferguson, 1971-72, and southwestern Alberta supports a diverse fauna with over 1978; Franclemont, 1973; Hodges, 1971, 1986; Lafontaine, 2,000 species of butterflies and moths (Order Lepidoptera) 1987; Munroe, 1972-74, 1976; Neunzig, 1986, 1990, 1997) recorded to date. -

An Annotated List of the Lepidoptera of Alberta, Canada

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 38: 1–549 (2010) Annotated list of the Lepidoptera of Alberta, Canada 1 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.38.383 MONOGRAPH www.pensoftonline.net/zookeys Launched to accelerate biodiversity research An annotated list of the Lepidoptera of Alberta, Canada Gregory R. Pohl1, Gary G. Anweiler2, B. Christian Schmidt3, Norbert G. Kondla4 1 Editor-in-chief, co-author of introduction, and author of micromoths portions. Natural Resources Canada, Northern Forestry Centre, 5320 - 122 St., Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6H 3S5 2 Co-author of macromoths portions. University of Alberta, E.H. Strickland Entomological Museum, Department of Biological Sciences, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E3 3 Co-author of introduction and macromoths portions. Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, K.W. Neatby Bldg., 960 Carling Ave., Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1A 0C6 4 Author of butterfl ies portions. 242-6220 – 17 Ave. SE, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2A 0W6 Corresponding authors: Gregory R. Pohl ([email protected]), Gary G. Anweiler ([email protected]), B. Christian Schmidt ([email protected]), Norbert G. Kondla ([email protected]) Academic editor: Donald Lafontaine | Received 11 January 2010 | Accepted 7 February 2010 | Published 5 March 2010 Citation: Pohl GR, Anweiler GG, Schmidt BC, Kondla NG (2010) An annotated list of the Lepidoptera of Alberta, Canada. ZooKeys 38: 1–549. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.38.383 Abstract Th is checklist documents the 2367 Lepidoptera species reported to occur in the province of Alberta, Can- ada, based on examination of the major public insect collections in Alberta and the Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes.