British Journal for Military History Military Journal for British

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clarecastle and Ballyea in the Great War

Clarecastle and Ballyea in the Great War By Ger Browne Index Page : Clarecastle and Ballyea during the Great War Page : The 35 Men from Clarecastle and Ballyea who died in the Great War and other profiles Page 57 : The List of those from Clarecastle and Ballyea in the Great War Page : The Soldiers Houses in Clarecastle and Ballyea Page : The Belgian Refugees in Clarecastle. Page : Clarecastle and Ballyea men in WW2 1 Clarecastle and Ballyea During the Great War Ennis Road Blacksmith Power’s Pub Military Barracks Train Station Main Street RIC Barracks Creggaun Clarecastle Harbour I would like to thank Eric Shaw who kindly gave me a tour of Clarecastle and Ballyea, and showed me all the sites relevant to WW1. Eric’s article on the Great War in the book ‘Clarecastle and Ballyea - Land and People 2’ was an invaluable source of information. Eric also has been a great help to me over the past five years, with priceless information on Clare in WW1 and WW2. If that was not enough, Dr Joe Power, another historian from Clarecastle published his excellent book ‘Clare and the Great War’ in 2015. Clarecastle and Ballyea are very proud of their history, and it is a privilege to write this booklet on its contribution to the Great War. 2 Main Street Clarecastle Michael McMahon: Born in Sixmilebridge, lived in Clarecastle, died of wounds 20th Aug 1917 age 25, Royal Dublin Fusiliers 1st Bn 40124, 29th Div, G/M in Belgium. Formerly with the Royal Munster Fusiliers. Son of Pat and Kate McMahon, and husband of Mary (Taylor) McMahon (she remained a war widow for the rest of her life), Main Street, Clarecastle. -

Reel-To-Real: Intimate Audio Epistolarity During the Vietnam War Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requireme

Reel-to-Real: Intimate Audio Epistolarity During the Vietnam War Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Alan Campbell, B.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Ryan T. Skinner, Advisor Danielle Fosler-Lussier Barry Shank 1 Copyrighted by Matthew Alan Campbell 2019 2 Abstract For members of the United States Armed Forces, communicating with one’s loved ones has taken many forms, employing every available medium from the telegraph to Twitter. My project examines one particular mode of exchange—“audio letters”—during one of the US military’s most trying and traumatic periods, the Vietnam War. By making possible the transmission of the embodied voice, experiential soundscapes, and personalized popular culture to zones generally restricted to purely written or typed correspondence, these recordings enabled forms of romantic, platonic, and familial intimacy beyond that of the written word. More specifically, I will examine the impact of war and its sustained separations on the creative and improvisational use of prosthetic culture, technologies that allow human beings to extend and manipulate aspects of their person beyond their own bodies. Reel-to-reel was part of a constellation of amateur recording technologies, including Super 8mm film, Polaroid photography, and the Kodak slide carousel, which, for the first time, allowed average Americans the ability to capture, reify, and share their life experiences in multiple modalities, resulting in the construction of a set of media-inflected subjectivities (at home) and intimate intersubjectivities developed across spatiotemporal divides. -

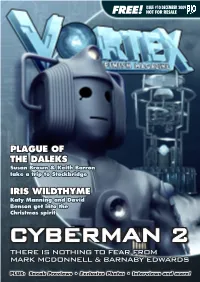

Plague of the Daleks Iris Wildthyme

ISSUE #10 DECEMBER 2009 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE PLAGUE OF THE DALEKS Susan Brown & Keith Barron take a trip to Stockbridge IRIS WILDTHYME Katy Manning and David Benson get into the Christmas spirit CYBERMAN 2 THERE IS NOTHING TO FEAR FROM MARK MCDONNELL & barnaby EDWARDS PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL THE BIG FINISH SALE Hello! This month’s editorial comes to you direct Now, this month, we have Sherlock Holmes: The from Chicago. I know it’s impossible to tell if that’s Death and Life, which has a really surreal quality true, but it is, honest! I’ve just got into my hotel to it. Conan Doyle actually comes to blows with Prices slashed from 1st December 2009 until 9th January 2010 room and before I’m dragged off to meet and his characters. Brilliant stuff by Holmes expert greet lovely fans at the Doctor Who convention and author David Stuart Davies. going on here (Chicago TARDIS, of course), I And as for Rob’s book... well, you may notice on thought I’d better write this. One of the main the back cover that we’ll be launching it to the public reasons we’re here is to promote our Sherlock at an open event on December 19th, at the Corner Holmes range and Rob Shearman’s book Love Store in London, near Covent Garden. The book will Songs for the Shy and Cynical. Have you bought be on sale and Rob will be signing and giving a either of those yet? Come on, there’s no excuse! couple of readings too. -

A History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference To

The History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference to the Command of Brigadier-General Frank Percy Crozier by Michael Anthony Taylor A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract 119 Brigade, 40th Division, had an unusual origin as a ‘left-over’ brigade of the Welsh Army Corps and was the only completely bantam formation outside 35th Division. This study investigates the formation’s national identity and demonstrates that it was indeed strongly ‘Welsh’ in more than name until 1918. New data on the social background of men and officers is added to that generated by earlier studies. The examination of the brigade’s actions on the Western Front challenges the widely held belief that there was an inherent problem with this and other bantam formations. The original make-up of the brigade is compared with its later forms when new and less efficient units were introduced. -

Download Book

0111001001101011 01THE00101010100 0111001001101001 010PSYHOLOGY0111 011100OF01011100 010010010011010 0110011SILION011 01VALLEY01101001 ETHICAL THREATS AND EMOTIONAL UNINTELLIGENCE 01001001001110IN THE TECH INDUSTRY 10 0100100100KATY COOK 110110 0110011011100011 The Psychology of Silicon Valley “As someone who has studied the impact of technology since the early 1980s I am appalled at how psychological principles are being used as part of the busi- ness model of many tech companies. More and more often I see behaviorism at work in attempting to lure brains to a site or app and to keep them coming back day after day. This book exposes these practices and offers readers a glimpse behind the “emotional scenes” as tech companies come out psychologically fir- ing at their consumers. Unless these practices are exposed and made public, tech companies will continue to shape our brains and not in a good way.” —Larry D. Rosen, Professor Emeritus of Psychology, author of 7 books including The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High Tech World “The Psychology of Silicon Valley is a remarkable story of an industry’s shift from idealism to narcissism and even sociopathy. But deep cracks are showing in the Valley’s mantra of ‘we know better than you.’ Katy Cook’s engaging read has a message that needs to be heard now.” —Richard Freed, author of Wired Child “A welcome journey through the mind of the world’s most influential industry at a time when understanding Silicon Valley’s motivations, myths, and ethics are vitally important.” —Scott Galloway, Professor of Marketing, NYU and author of The Algebra of Happiness and The Four Katy Cook The Psychology of Silicon Valley Ethical Threats and Emotional Unintelligence in the Tech Industry Katy Cook Centre for Technology Awareness London, UK ISBN 978-3-030-27363-7 ISBN 978-3-030-27364-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27364-4 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020 This book is an open access publication. -

The Blue Cap Journal of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers Association Vol

THE BLUE CAP JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL DUBLIN FUSILIERS ASSOCIATION VOL. 23. DECEMBER 2018 Reflections on 1918 Tom Burke On 11 November 1917, at a meeting between Ludendorff and a select group of his advisers in Mons where the British and Germans had clashed back in August 1914, it was decided to knock Britain out of the war before any American entry into the war with decisive numbers of boots on the ground.1 As 1918 opened, the Western, Italian, Salonica and Turkish fronts were each the scene of no large-scale offensives but of sporadic fighting characterised by repeated raids and counter-raids.2 In terms of the eastern front, the German defeat of Russia and her consequential withdrawal from the war, presented Ludendorff and his commanders with a window of opportunity to end the war in the west. One result of Russia’s defeat was the accumulation of munition stocks and the release of large numbers of German troops for an offensive in the west.3 One estimate of the number of German troops available for transfer from east to west was put at 900,000 men.4 According to Gary Sheffield, ‘in the spring of 1918 the Germans could deploy 192 divisions, while the French and British could only muster 156.’ 5 However, according to John Keegan, the Allies had superior stocks of war material. For example, 4,500 Allied aircraft against 3,670 German; 18,500 Allied artillery weapons against 14,000 Germans and 800 Allied tanks against ten German.6 Yet despite this imbalance in material, the combination of a feeling of military superiority, and, acting before the Allies could grow in strength through an American entry along with rising economic and domestic challenges in Germany, all combined to prompt Ludendorff to use the opportunity of that open window and attack the British as they had planned to do back in Mons on 11 November 1917 at a suitable date in the spring of 1918. -

Notice. Reduction of Fees. the Average Prick of Brown Or

3913 Second Lieutenant William George Martin to be NOTICE. First Lieutenant, vice Earle. Dated 6th November, 1854. County Court? Registry, 1, Parliament-street, Westminster. Second Captain Adolphus Frederick Connell to be Captain, vice Pack-Beresford, retired by REDUCTION OF FEES. resignation of his Commission. Dated 24th THE Lords Commissioners of Her Majesty's November, 1854. Treasury have been pleased to order that the fol- First Lieutenant the Honourable Leonard Allen lowing reduced fees should be"taken for Searches, Addington to be Second Captain, vice Connell. &c., namely : Dated 24th November, 1854. Table of Fees. Second Lieutenant Philip Henry Sandilands to. s. d. be First Lieutenant, vice Addington. Dated For every search for a judgment or peti- 24th November, 1854. tion for protection made at the Registry 0 - 6 For forty searches, to be made within two months (to be paid in advance) . .10 0 For every certificate of search, obtained either through the Clerk of the Court or Commission signed by the Queen. by a letter to the Registrar 20 For having the record of any judgment City of Edinburgh Artillery Regiment of Militia. removed from the register (to be paid to Thomas Richardson Griffiths, Gent., to be Adju- the Clerk of the Court) ...... 1 6 tant. Dated 10th November, 1854. The registry of county courts' judgments was established to afford to traders a ready means of Commissions signed by the Lord Lieutenant of the ascertaining the solvency of parties, and to enable County Palatine of Lancaster. executors and administrators to discover what judgment debts they are bound to satisfy. -

How Will the Seventh Doctor Cope with a Companion Who Despises

ISSUE #12 FEBRUARY 2010 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE JACQUELINE RAYNER We chat to the writer of The Suffering DAVID GARFIELD chalks up another memorable Who villain in The Hollows of Time REBECCA’S WORLD is finally here! HOWSYLV’ WILL THES SEVEN NEMESISTH DOCTOR COPE WITH A COMPANION WHO DESPISES HIM? PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL It’s February and it productions and we feels like I’ve only just also read out listeners’ recovered from that week emails and comment of Big Finish podcasts we on them… mostly in a produced in December! constructive fashion. If What do you mean you want to take part, you didn’t hear them? you can email us on Naturally, we’ve already [email protected]. continued with our If you want to make an January podcast and the audio appearance in February one will be on the podcast, why not THE DOCTOR’S the way soon. send us an mp3 version So I thought it was with your email? I think NEW COMPANION high time I brought the that would be fun. IS ALSO HIS podcasts to the attention of SWORN ENEMY! any of you out there who The newest haven’t yet discovered feature, which we STARRING them. We put them up on started in December, the Big Finish site at least SYLVESTER MCCOY AS THE DOCTOR is the shameless once a month. They usually contain a chaotic mixture AND TRACEY CHILDS AS KLEIN phenomenon known as ‘the podcast competition’. of David Richardson, Paul Spragg, Alex Mallinson, In each podcast from now on, we will be giving me and possibly a guest star, talking about the latest away a prize! Now that’s what I call bribery! A THOUSAND TINY WINGS releases, tea and what we’re eating for lunch. -

Pro Patria Commemorating Service

PRO PATRIA COMMEMORATING SERVICE Forward Representative Colonel Governor of South Australia His Excellency the Honorable Hieu Van Le, AO Colonel Commandant The Royal South Australia Regiment Brigadier Tim Hannah, AM Commanding Officer 10th/27th Battalion The Royal South Australia Regiment Lieutenant Colonel Graham Goodwin Chapter Title One Regimental lineage Two Colonial forces and new Federation Three The Great War and peace Four The Second World War Five Into a new era Six 6th/13th Light Battery Seven 3rd Field Squadron Eight The Band Nine For Valour Ten Regimental Identity Eleven Regimental Alliances Twelve Freedom of the City Thirteen Sites of significance Fourteen Figures of the Regiment Fifteen Scrapbook of a Regiment Sixteen Photos Seventeen Appointments Honorary Colonels Regimental Colonels Commanding Officers Regimental Sergeants Major Nineteen Commanding Officers Reflections 1987 – 2014 Representative Colonel His Excellency the Honorable Hieu Van Le AO Governor of South Australia His Excellency was born in Central Vietnam in 1954, where he attended school before studying Economics at the Dalat University in the Highlands. Following the end of the Vietnam War, His Excellency, and his wife, Lan, left Vietnam in a boat in 1977. Travelling via Malaysia, they were one of the early groups of Vietnamese refugees to arrive in Darwin Harbour. His Excellency and Mrs Le soon settled in Adelaide, starting with three months at the Pennington Migrant Hostel. As his Tertiary study in Vietnam was not recognised in Australia, the Governor returned to study at the University of Adelaide, where he earned a degree in Economics and Accounting within a short number of years. In 2001, His Excellency’s further study earned him a Master of Business Administration from the same university. -

Connecticut College Alumnae News, August 1954 Connecticut College

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Alumni News Archives 8-1954 Connecticut College Alumnae News, August 1954 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/alumnews Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "Connecticut College Alumnae News, August 1954" (1954). Alumni News. Paper 108. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/alumnews/108 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Archives at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni News by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Connecticut College Alumnae News Playing fields and Long Island Sound seen from Palmer Library, August, 1954 COLLEGE CALENDAR NOVEMBER 1954 - JUNE 1955 NOVEMBER FEBRUARY 7 Monday Second semester begins, 8 A.M. 24 Wednesday Thanksgiving recess begins, 11: lO A.M. 11 Friday Period for change of individual pro- Thanksgiving recess ends, 11 P.M. 28 Sunday grams ends, 4 P. M. APRIL DECEMBER 2 Saturday Spring recess begins, 11: 10 A.M. Spring recess ends, 11 P.M. 18 Saturday Christmas recess begins, 11: 10 A.M. 12 Tuesday MAY Period for election of courses for JANUARY 9-13 1955-56 4 Tuesday Christmas recess ends, 11 P.M. Friday Period ends, 4 P.M. Registration foe second semester 13 lO-14 Friday Comprehensive examinations for Period closes, 4 P,M. 27 14 Friday seniors Reading period 17-22 23-28 Reading period Review period 24~25 Monday Review period 26 Wednesday Mid-year examinations begin 30 31 Tuesday Final examinations begin FEBRUARY JUNE 3 Thursday Mid-year examinations end 8 Wednesday Final examinations end Commencement 6 Sunday Inter-semester recess ends, 11 P.M. -

Geoffrey Beevers Is the Master*

ISSUE 40 • JUNE 2012 NOT FOR RESALE FREE! GEOFFREY BEEVERS IS THE MASTER* PLUS! MARK STRICKSON & SARAH SUTTON Nyssa and Turlough Interviewed! I KNOW THAT VOICE... Famous names in Big Finish! *AND YOU WILL OBEY HIM! SNEAK PREVIEWS EDITORIAL AND WHISPERS e love stories. You’ll be hearing those words from us a lot more over the coming months. We’re only saying it because it’s the truth. And in THE FOURTH DOCTOR ADVENTURES a way, you’ve been hearing it from us since we started all this, right SERIES 3 W back in 1998, with Bernice Summerfield! Every now and then, I think it’s a good idea to stop and consider why we do 2014 might seem what we do; especially when, as has happened recently, we’ve been getting such a long way away, a pounding by a vociferous minority in online forums. As you may know, there but it’ll be here have been some teething problems with the changeover to our new website. before you know There was a problem with the data from the old site, relating to the downloads it – and so we’re in customers’ accounts. It seems that the information was not complete and had already in the some anomalous links in it, which meant that some downloads didn’t appear and studio recording others were allocated incorrectly. Yes, we accidentally gave a lot of stuff away! And, the third series of in these cash-strapped times, that was particularly painful for us. Thanks to all of Fourth Doctor Adventures, once again you who contacted us to say you wouldn’t take advantage of these – shall we say featuring the Doctor and Leela. -

List of Recommended Great War Websites – 18 December 2020

CEF Study Group Recommended Great War Websites - 18 D e c e m b e r 2020 - http://cefresearch.ca/phpBB3/ Dwight G Mercer /aka Borden Battery – R e g i n a , C a n a d a © Canadian Expeditionary Force Study Group – Recommended Great War Websites – December 2020 he 18 December 2020 edition of the Recommended Great War Websites by the Canadian Expeditionary Force Study Group is part of the CEF Study Group internet T discussion forum dedicated to the study, sharing of information and discussion related to the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) in the Great War – in an “Open Source” mode. This List is intended to assist the reader in their research of a specific Great War theme with emphasis on the Canadian experience. Further, this recommended List of Great War websites is intended to compliment the active discourse on the Forum by its members. The function of the CEF Study Group List of Recommended Great War Websites (circa 2005) is to serve as a directory for the reader of the Great War. These websites have been vetted and grouped into logical sections. Each abstract, in general, attempts to provide a "key word" search to find websites of immediate interest. Surfing this List is one of the objectives. All aspects of the Canadian Expeditionary Force are open to examination. Emphasis is on coordinated study, information exchange, civil and constructive critiquing of postings and general mutual support in the research and study of the CEF. Wherever possible, we ask that members provide a reference source for any information posted.