An Environmental Analysis of FCEV and H2-ICE Vehicles Using the Ecoscore Methodology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fuel Cells on Bio-Gas

Fuel Cells on Bio-Gas 2009 Michigan Water Environment Association's (MWEA) Biosolids and Energy Conference Robert J. Remick, PhD March 4, 2009 NREL/PR-560-45292 NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC. Wastewater Treatment Plants • WWTP operators are looking for opportunities to utilize biogas as a renewable energy source. • Majority use biogas through boilers for reheating • Interest is growing in distributed generation, especially where both electricity and fuel costs are high. • Drivers for the decision to purchase fuel cells – Reliability – Capital and O&M costs – Availability of Government Incentives National Renewable Energy Laboratory Innovation for Our Energy Future Anaerobic Digestion and Biogas • Anaerobic digestion is a process used to stabilize Range of Biogas Compositions wastewater sludge before final disposal. Methane 50% – 75% Carbon Dioxide 25% – 50% • The process uses Nitrogen 0% – 10% microorganisms in the Hydrogen 0% – 1% absence of oxygen to Sulfur Species 0% – 3% convert organic Oxygen 0% – 2% materials to biogas. National Renewable Energy Laboratory Innovation for Our Energy Future WWTP Co-Gen Market • There are over 16,800 WWTP in the U.S. • 615 facilities with flows > 3 mgd that use anaerobic digestion • 215 do not use their biogas but flare it instead. • California has the highest number of municipal facilities using anaerobic digestion, about 102, of which 25 do not use their biogas. -

Comparison of Hydrogen Powertrains with the Battery Powered Electric Vehicle and Investigation of Small-Scale Local Hydrogen Production Using Renewable Energy

Review Comparison of Hydrogen Powertrains with the Battery Powered Electric Vehicle and Investigation of Small-Scale Local Hydrogen Production Using Renewable Energy Michael Handwerker 1,2,*, Jörg Wellnitz 1,2 and Hormoz Marzbani 2 1 Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, University of Applied Sciences Ingolstadt, Esplanade 10, 85049 Ingolstadt, Germany; [email protected] 2 Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, School of Engineering, Plenty Road, Bundoora, VIC 3083, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Climate change is one of the major problems that people face in this century, with fossil fuel combustion engines being huge contributors. Currently, the battery powered electric vehicle is considered the predecessor, while hydrogen vehicles only have an insignificant market share. To evaluate if this is justified, different hydrogen power train technologies are analyzed and compared to the battery powered electric vehicle. Even though most research focuses on the hydrogen fuel cells, it is shown that, despite the lower efficiency, the often-neglected hydrogen combustion engine could be the right solution for transitioning away from fossil fuels. This is mainly due to the lower costs and possibility of the use of existing manufacturing infrastructure. To achieve a similar level of refueling comfort as with the battery powered electric vehicle, the economic and technological aspects of the local small-scale hydrogen production are being investigated. Due to the low efficiency Citation: Handwerker, M.; Wellnitz, and high prices for the required components, this domestically produced hydrogen cannot compete J.; Marzbani, H. Comparison of with hydrogen produced from fossil fuels on a larger scale. -

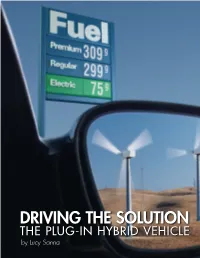

EPRI Journal--Driving the Solution: the Plug-In Hybrid Vehicle

DRIVING THE SOLUTION THE PLUG-IN HYBRID VEHICLE by Lucy Sanna The Story in Brief As automakers gear up to satisfy a growing market for fuel-efficient hybrid electric vehicles, the next- generation hybrid is already cruis- ing city streets, and it can literally run on empty. The plug-in hybrid charges directly from the electricity grid, but unlike its electric vehicle brethren, it sports a liquid fuel tank for unlimited driving range. The technology is here, the electricity infrastructure is in place, and the plug-in hybrid offers a key to replacing foreign oil with domestic resources for energy indepen- dence, reduced CO2 emissions, and lower fuel costs. DRIVING THE SOLUTION THE PLUG-IN HYBRID VEHICLE by Lucy Sanna n November 2005, the first few proto vide a variety of battery options tailored 2004, more than half of which came from Itype plugin hybrid electric vehicles to specific applications—vehicles that can imports. (PHEVs) will roll onto the streets of New run 20, 30, or even more electric miles.” With growing global demand, particu York City, Kansas City, and Los Angeles Until recently, however, even those larly from China and India, the price of a to demonstrate plugin hybrid technology automakers engaged in conventional barrel of oil is climbing at an unprece in varied environments. Like hybrid vehi hybrid technology have been reluctant to dented rate. The added cost and vulnera cles on the market today, the plugin embrace the PHEV, despite growing rec bility of relying on a strategic energy hybrid uses battery power to supplement ognition of the vehicle’s potential. -

Waste-To-Energy and Fuel Cell Technologies Overview

Innovation for Our Energy Future Waste-to-Energy and Fuel Cell ThTechnol ogi es O vervi ew Presented to: DOD-DOE Waste-to- Energy Workshop Dr. Robert J. Remick January 13, 2011 Capital Hilton Hotel Washington, DC NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC. Global Approach for Using Biogas Innovation for Our Energy Future Anaerobic Digestion of Organic Wastes is a Good Source of Methane. Organic waste + methanogenic bacteria → methane (CH4) Issues: High levels of contamination Time varying output of gas quantity and quality Photo courtesy of Dos Rios Water Recycling Center, San Antonio, TX Innovation for Our Energy Future Opportunities for Methane Production via Anaerobic Digestion • Breweries (~73 Watts per barrel of beer) • Municipal Waste Water Treatment Plants (~4 W/person) • Industrial-scale Food Processing • Landfills • Dairy and Pig Farms (~200 W/Cow) • Pulp and Paper Mills Innovation for Our Energy Future Stationary Fuel Cell Products Currently on the Maaetrket aaere Confi gured to Oper ate on Natura l Gas UTC Power, Inc. PureCell 400 FlCllFuelCell EIEnergy Inc. DFC 300, 1500, an d 3000 Bloom Energy, Inc. ES-5000 Energy Server Waste processes that produce methane, like anaerobic digestion of organic matter, are most easily mated to these fuel cell systems. Innovation for Our Energy Future Comparison by Generator Type (based on 40-million SCF* of bioggpyas per year** ) Generator Type Megawatt‐hours/year PAFC 2,900 MCFC 3,300 Micro‐tbiturbine 1, 800 Reciprocating Engine 1,500 * ~830 Btu/SCF (HHV) ** WWTP serving a community of about 110,000 people This comparison ignores the fact that generators do not come in an infinite range of sizes. -

Making Markets for Hydrogen Vehicles: Lessons from LPG

Making Markets for Hydrogen Vehicles: Lessons from LPG Helen Hu and Richard Green Department of Economics and Institute for Energy Research and Policy University of Birmingham Birmingham B15 2TT United Kingdom Hu: [email protected] Green: [email protected] +44 121 415 8216 (corresponding author) Abstract The adoption of liquefied petroleum gas vehicles is strongly linked to the break-even distance at which they have the same costs as conventional cars, with very limited market penetration at break-even distances above 40,000 km. Hydrogen vehicles are predicted to have costs by 2030 that should give them a break-even distance of less than this critical level. It will be necessary to ensure that there are sufficient refuelling stations for hydrogen to be a convenient choice for drivers. While additional LPG stations have led to increases in vehicle numbers, and increases in vehicles have been followed by greater numbers of refuelling stations, these effects are too small to give self-sustaining growth. Supportive policies for both vehicles and refuelling stations will be required. 1. Introduction While hydrogen offers many advantages as an energy vector within a low-carbon energy system [1, 2, 3], developing markets for hydrogen vehicles is likely to be a challenge. Put bluntly, there is no point in buying a vehicle powered by hydrogen, unless there are sufficient convenient places to re-fuel it. Nor is there any point in providing a hydrogen refuelling station unless there are vehicles that will use the facility. What is the most effective way to get round this “chicken and egg” problem? Data from trials of hydrogen vehicles can provide information on driver behaviour and charging patterns, but extrapolating this to the development of a mass market may be difficult. -

Prospects for Bi-Fuel and Flex-Fuel Light Duty Vehicles

Prospects for Bi-Fuel and Flex-Fuel Light-Duty Vehicles An MIT Energy Initiative Symposium April 19, 2012 MIT Energy Initiative Symposium on Prospects for Bi-Fuel and Flex-Fuel Light-Duty Vehicles | April 19, 2012 C Prospects for Bi-Fuel and Flex-Fuel Light-Duty Vehicles An MIT Energy Initiative Symposium April 19, 2012 ABOUT THE REPORT Summary for Policy Makers The April 19, 2012, MIT Energy Initiative Symposium addressed Prospects for Bi-Fuel and Flex-Fuel Light-Duty Vehicles. The symposium focused on natural gas, biofuels, and motor gasoline as fuels for light-duty vehicles (LDVs) with a time horizon of the next two to three decades. The important transportation alternatives of electric and hybrid vehicles (this was the subject of the 2010 MITEi Symposium1) and hydrogen/fuel-cell vehicles, a longer-term alternative, were not considered. There are three motivations for examining alternative transportation fuels for LDVs: (1) lower life cycle cost of transportation for the consumer, (2) reduction in the greenhouse gas (GHG) footprint of the transportation sector (an important contributor to total US GHG emissions), and (3) improved energy security resulting from greater use of domestic fuels and reduced liquid fuel imports. An underlying question is whether a flex-fuel/bi-fuel mandate for new LDVs would drive development of a robust alternative fuels market and infrastructure versus alternative fuel use requirements. Symposium participants agreed on these motivations. However, in this symposium in contrast to past symposiums, there was a striking lack of agreement about the direction to which the market might evolve, about the most promising technologies, and about desirable government action. -

Development of Business Cases for Fuel Cells and Hydrogen Applications for Regions and Cities FCH Bikes

Development of Business Cases for Fuel Cells and Hydrogen Applications for Regions and Cities FCH Bikes Brussels, Fall 2017 This compilation of application-specific information forms part of the study "Development of Business Cases for Fuel Cells and Hydrogen Applications for European Regions and Cities" commissioned by the Fuel Cells and Hydrogen 2 Joint Undertaking (FCH2 JU), N° FCH/OP/contract 180, Reference Number FCH JU 2017 D4259 . The study aims to support a coalition of currently more than 90 European regions and cities in their assessment of fuel cells and hydrogen applications to support project development. Roland Berger GmbH coordinated the study work of the coalition and provided analytical support. All information provided within this document is based on publically available sources and reflects the state of knowledge as of August 2017. 2 Table of Contents Topic Page A. Technology Introduction 4 B. Preliminary Business Case 9 3 A. Technology Introduction 4 A FC bikes offer almost 2.5 times the operating range of traditional e- bikes – Refuelling time only 2-6 minutes instead of up to 8 hours Fuel cell electric bikes 1/4 1 or more pictures of Brief description: Fuel cell electric bikes Use cases: Cities and regions can examples of the actual use compressed hydrogen gas as a fuel to use/promote fuel cell electric bikes for bike generate electricity via an energy converter (fuel sharing offerings and inner city services (e.g. applications, insert cell) assisting the rider's pedal power through an police patrolling, deliveries, -

Ahydrogen Economy

AHYDROGEN ECONOMY • Will motorists someday fill up theirtanks with hydrogen? Many complex challenges must be overcome before a hydrogen·fueled future can become a reality. Using hydrogen to fuel cars may eventually slash oil consumption and carbon emissions, but it will take some time BY JOAN OGDEN Developing cleaner power sources els. Liquid fuels derived from woody for transportation is perhaps the tricki plants or synthesized from tar sands or est piece of the energy puzzle. The dif coal may play important roles. Over the ficulty sterns from two discouraging long term, however, the most feasible facts. First, the number of vehicles ways to power vehicles with high effi worldwide, now 750 million, is expect ciency and zero emissions are through ed to triple by 2050, thanks largely to connections to the electric grid or the use the expanding buying power of custom of hydrogen as a transportation fuel. ers in China, India and other rapid Iy de Unfortunately, the commercializa veloping countries. And second, 97 per tion of electric vehicles has been stymied OVERVIEW cent of transportation fuel currently by a daunting obstacle: even large ar i,; Hydrogen fuel·cell comes from crude oil. rays of batteries cannot store enough cars could become In the near term, improving fuel charge to keep cars running for distanc commercially feasi economy is the best way to slow the rise es comparable to gasoline engines. For ble ifauto makers succeed In develop in oil use and greenhouse gas emissions this reason, most auto companies have ingsafe, Inexpen from cars and trucks. But even if auto abandoned the technology. -

Comparison Between Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles and Bio-Diesel Vehicles

Comparison between hydrogen fuel cell vehicles and bio-diesel vehicles Bent Sørensen Roskilde University, Institute of Mathematics and Physics, Energy & Environment Group Universitetsvej 1, DK-4000 Roskilde, Denmark web: http://mmf.ruc.dk/energy email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Performance simulation results are presented for fuel cell/battery hybrid vehicle concepts and for highly efficient combustion engine vehicles using bio-diesel fuel. The bio-diesel concept takes depar- ture in the commercial Volkswagen Lupo TDI-3L motorcar modeled for a road-based driving-cycle of mixed urban and highway segments. This is compared to new hybrid concepts using hydrogen as fuel. Theoretically, the fuel cell cars can achieve a higher average efficiency than the common-rail diesel engine used in the Lupo. However, in practice the difference is diminished. Ongoing develop- ment of low-weight batteries such as lithium-ion batteries for automotive uses (scaled up from the current versions used in consumer electronic devices) is essential for achieving the optimum hybrid vehicle performance. Assessment of alternative vehicle concepts must include economic and envi- ronmental impacts. These have been addressed by the life-cycle analysis methodology. Keywords: Hydrogen vehicles, hybrid fuel cell/battery car, common-rail diesel car, efficiency, envi- ronmental impacts 1. Introduction The aim of this communication is to compare fuel cell vehicles using hydrogen as a fuel with internal combustion vehicles using a biofuel such as biodiesel. Current biomass use in the energy sector is mostly by direct combustion. This is an inappropriate use, because biomass offers exceptional possibilities for covering energy needs for transportation, which are difficult to meet with any other sustainable energy source. -

Section 3.4 Fuel Cells

2016 FUEL CELLS SECTION 3.4 Fuel Cells Fuel cells efficiently convert diverse fuels directly into electricity without combustion, and they are key elements of a broad portfolio for building a competitive, secure, and sustainable clean energy economy. They offer a broad range of benefits, including reduced greenhouse gas emissions; reduced oil consumption; expanded use of renewable power (through the use of hydrogen derived from renewable resources as a transportation fuel as well as for energy storage and transmission); highly efficient energy conversion; fuel flexibility (use of diverse, domestic fuels, including hydrogen, natural gas, biogas, and methanol); reduced air pollution, criteria pollutants, water use; and highly reliable grid support. Fuel cells also have numerous advantages that make them appealing for end users, including quiet operation, low maintenance needs, and high reliability. Because of their broad applicability and diverse uses, fuel cells can address critical challenges in all energy sectors: commercial, residential, industrial, and transportation. The fuel cell industry had revenues of approximately $2.2 billion in 2014, an increase of almost $1 billion over revenues in 2013.1 The largest markets for fuel cells today are in stationary power, portable power, auxiliary power units, backup power, and material handling equipment. Approximately 155,000 fuel cells were shipped worldwide in the four-year period from 2010 through 2013, accounting for 510–583 MW of fuel cell capacity.2 In 2014 alone, more than 50,000 fuel cells accounting for over 180 MW of capacity were shipped.1 In transportation applications, manufacturers have begun to commercialize fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs). Hyundai and Toyota have recently introduced their FCEVs in the marketplace, and Honda is set to launch its new FCEV in the market in 2016. -

Key Specifications the Mirai Is a Fuel Cell Vehicle (FCV) Which Uses

Outline of the Mirai The Mirai is a fuel cell vehicle (FCV) which uses hydrogen as energy to generate electricity and power the vehicle. Fuel cell system The hydrogen that powers the Mirai, hydrogen, can be produced from various types of primary sources, making it a promising alternative to current energy sources. The Toyota Fuel Cell System (TFCS) combines proprietary fuel cell technology that includes the Toyota FC Stack and high-pressure hydrogen tanks with the hybrid technology. The TFCS has high energy efficiency compared with conventional internal combustion engines, along with superior environmental performance highlighted by zero emissions of CO2 and other pollutants during vehicle operation. The hydrogen tanks can be refuelled in approximately three minutes *1, and with an ample cruising range, the system promises convenience on par with gasoline engine vehicles. The Mirai’s value The Mirai offers the kind of exceptional value drivers would expect from a next-generation car: distinctive exterior design, excellent acceleration performance and unmatched quietness thanks to motor propulsion at all speeds, in addition to enhanced driving pleasure due to a low center of gravity bringing greater handling stability. *1 Toyota measurement under SAEJ2601 standards (ambient temperature: 20 °C; hydrogen tank pressure when fueled: 10 MPa). Fueling time varies with hydrogen fueling pressure and ambient temperature. Key Specifications Height 1,535 mm Wheelbase 2,780 mm Width 1,815 mm Length 4,890 mm Driving performance Dimensions / seating -

Hydrogen Fuel Cell Road Vehicles and Their Infrastructure: an Option Towards an Environmentally Friendly Energy Transition

energies Article Hydrogen Fuel Cell Road Vehicles and Their Infrastructure: An Option towards an Environmentally Friendly Energy Transition Olivier Bethoux 1,2 1 Laboratoire de Génie Electrique et Electronique de Paris, CNRS, Group Sorbonne Université, 75252 Paris, France; [email protected]; Tel.: +331-69-85-16-56 2 Laboratoire de Génie Electrique et Electronique de Paris, CNRS, CentraleSupélec, Université Paris-Saclay, 91192 Gif-sur-Yvette, France Received: 22 September 2020; Accepted: 17 November 2020; Published: 23 November 2020 Abstract: The latest pre-production vehicles on the market show that the major technical challenges posed by integrating a fuel cell system (FCS) within a vehicle—compactness, safety, autonomy, reliability, cold starting—have been met. Regarding the ongoing maturity of fuel cell systems dedicated to road transport, the present article examines the advances still needed to move from a functional but niche product to a mainstream consumer product. It seeks to address difficulties not covered by more traditional innovation approaches. At least in long-distance heavy-duty vehicles, fuel cell vehicles (FCVs) are going to play a key role in the path to zero-emissions in one or two decades. Hence the present study also addresses the structuring elements of the complete chain: the latter includes the production, storage and distribution of hydrogen. Green hydrogen appears to be one of the potential uses of renewable energies. The greener the electricity is, the greater the advantage for hydrogen since it permits to economically store large energy quantities on seasonal rhythms. Moreover, natural hydrogen might also become an economic reality pushing the fuel cell vehicle to be a competitive and environmentally friendly alternative to the battery electric vehicle.