Biogeography and Spatio-Temporal Diversification of Selenidera And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toucans, and Not Only a First Breeding of Each, Toucans but Several Generations - a Testament to His Avicultural Gift

one, but several species of toucans, and not only a First Breeding of each, Toucans but several generations - a testament to his avicultural gift. in Aviculture at the Millennium Mr. Todd did more than break new ground (which he subsequently and by Jerry Jennings, Fallbrook, CA notably repeated with penguins at Sea World), he created a "cook book" recipe for the repetition ofhis feat for all who would simply follow directions. Interpretive renditions of his opus gen erally would not suffice - simply fol low the steps. A little compatibility here, a little nest log there, etc., and a great result would be forthcoming. Few have followed in those illustri ous footsteps, but I had to give it a try. I never was a good cook, so this was a difficult task, or so I thought. Needless to say, it was surprisingly eas ier to do than expected, and today Emerald Forest Bird Gardens has become a center for the reproduction of many species of toucans, toucanets, and aracaris. Toucans are not well established in aviculture today in spite of the great introduction pioneered by Todd in the mid sixties. Only a couple of species, Red-billed Toucan oUJned by the author. the Green Aracari and the Emerald Toucanet could be considered "safe" Channel-billed Toucan in the collection ofthe alltbor. oucans are as familiar as breakfast cereal at the super market, as magnificent as a clown, and as exotic as the mystical places of our fantasies. Everyone seems to know who "Fruit Loops" is, and understands that this silly looking creature has, at the very least, a good sense of humor. -

Birding with Jim and Cindy

CHEEPERS SPRING 2014 TRIP REPORT BY COMMON NAME Tinamidae Cathartidae Little Tinamou Black Vulture Turkey Vulture Anatidae King Vulture Blue-winged Teal Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Pandionidae Masked Duck Osprey Cracidae Accipitridae Gray-headed Chachalaca Roadside Hawk Common Black-Hawk Phaethontidae Swainson´s Hawk Red-billed Tropicbird Broad-winged Hawk Double-toothed Kite Fregatidae Plumbeous Kite Magnificent Frigatebird Swallow-tailed Kite Ornate Hawk-Eagle Sulidae White-tailed Kite Brown Booby Falconidae Pelecanidae Laughing Falcon Brown Pelican Peregrine falcon Yellow-headed Caracara Ardeidae Crested Caracara Yellow-crowned Nigth-Heron Green Heron Rallidae Cattle Egret Gray-necked Wood-rail Little Blue Heron White-throated Crake Great Egret American Coot Great Blue Heron Purple Gallinule Tricolored Heron Common Moorhen Snowy Egret Boat-billed Heron Charadriidae Least Bittern Collared Plover Black-bellied Plover Threskiornithidae Semipalmated Plover Green Ibis Southern Lapwing Wilson's Plover Jacanidae Caprimulgidae Northern Jacana Lesser Nighthawk Recurvirostridae Nyctibiidae Black-necked Stilt Common Potoo Scolopacidae Apodidae Solitary Sandpiper White-collar Swift Spotted sandpiper Lesser Swallow-tailed Swift Ruddy turnstone Gray-rumped Swift Sanderling Greater Yellowlegs Trochilidae Least Sandpiper Long-billed Hermit Pectoral Sandpiper Stripe-throated Hermit Rufous-tailed Hummingbird Laridae White-necked Jacobin Royal Tern Violet-crowned Woodnymph Sandwich Tern Band-tailed Barbthroat Laughing Gull Blue-chested Hummingbird Franklin´s -

Brazil's Eastern Amazonia

The loud and impressive White Bellbird, one of the many highlights on the Brazil’s Eastern Amazonia 2017 tour (Eduardo Patrial) BRAZIL’S EASTERN AMAZONIA 8/16 – 26 AUGUST 2017 LEADER: EDUARDO PATRIAL This second edition of Brazil’s Eastern Amazonia was absolutely a phenomenal trip with over five hundred species recorded (514). Some adjustments happily facilitated the logistics (internal flights) a bit and we also could explore some areas around Belem this time, providing some extra good birds to our list. Our time at Amazonia National Park was good and we managed to get most of the important targets, despite the quite low bird activity noticed along the trails when we were there. Carajas National Forest on the other hand was very busy and produced an overwhelming cast of fine birds (and a Giant Armadillo!). Caxias in the end came again as good as it gets, and this time with the novelty of visiting a new site, Campo Maior, a place that reminds the lowlands from Pantanal. On this amazing tour we had the chance to enjoy the special avifauna from two important interfluvium in the Brazilian Amazon, the Madeira – Tapajos and Xingu – Tocantins; and also the specialties from a poorly covered corner in the Northeast region at Maranhão and Piauí states. Check out below the highlights from this successful adventure: Horned Screamer, Masked Duck, Chestnut- headed and Buff-browed Chachalacas, White-crested Guan, Bare-faced Curassow, King Vulture, Black-and- white and Ornate Hawk-Eagles, White and White-browed Hawks, Rufous-sided and Russet-crowned Crakes, Dark-winged Trumpeter (ssp. -

Ecuador: HARPY EAGLE & EAST ANDEAN FOOTHILLS EXTENSION

Tropical Birding Trip Report Ecuador: HARPY EAGLE & East Andean Foothills Extension (Jan-Feb 2021) A Tropical Birding custom extension Ecuador: HARPY EAGLE & EAST ANDEAN FOOTHILLS EXTENSION th nd 27 January - 2 February 2021 The main motivation for this custom extension was this Harpy Eagle. This was one of an unusually accessible nesting pair near the Amazonian town of Limoncocha that provided a worthy add-on to The Andes Introtour in northwest Ecuador that preceded this (Jose Illanes/Tropical Birding Tours). Guided by Jose Illanes Birds in the photos within this report are denoted in RED, all photos were taken by the Tropical Birding guide. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Ecuador: HARPY EAGLE & East Andean Foothills Extension (Jan-Feb 2021) INTRODUCTION This custom extension trip was set up for one person who simply could not get enough of Ecuador…John had just finished Ecuador: The Andes Introtour, in the northwest of the country, and also joined the High Andes Extension to that tour, which sampled the eastern highlands too. However, he was still missing vast chunks of this small country that is bursting with bird diversity. Most importantly, he was keen to get in on the latest “mega bird” in Ecuador, a very accessible Harpy Eagle nest, near a small Amazonian town, which had been hitting the local headlines and drawing the few birding tourists in the country at this time to come see it. With this in mind, TROPICAL BIRDING has been offering custom add-ons to all of our Ecuador offerings (for 2021 and 2022) to see this Harpy Eagle pair, with only three extra days needed to see it. -

Arils As Food of Tropical American Birds

Condor, 82:3142 @ The Cooper Ornithological society 1980 ARILS AS FOOD OF TROPICAL AMERICAN BIRDS ALEXANDER F. SKUTCH ABSTRACT.-In Costa Rica, 16 kinds of trees, lianas, and shrubs produce arillate seeds which are eaten by 95 species of birds. These are listed and compared with the birds that feed on the fruiting spikes of Cecropia trees and berries of the melastome Miconia trinervia. In the Valley of El General, on the Pacific slope of southern Costa Rica, arillate seeds and berries are most abundant early in the rainy season, from March to June or July, when most resident birds are nesting and northbound migrants are leaving or passing through. The oil-rich arils are a valuable resource for nesting birds, especially honeycreepers and certain woodpeck- ers, and they sustain the migrants. Vireos are especially fond of arils, and Sulphur-bellied Flycatchers were most numerous when certain arillate seeds were most abundant. Many species of birds take arils from the same tree or vine without serious competition. However, at certain trees with slowly opening pods, birds vie for the contents while largely neglecting other foods that are readily available. Although many kinds of fruits eaten by during the short time that the seed remains birds may be distinguished morphological- in the alimentary tract of a small bird. ly, functionally they fall into two main Wallace (1872) described how the Blue- types, exemplified by the berry and the pod tailed Imperial Pigeon (Duculu concinnu) containing arillate seeds. Berries and ber- swallows the seed of the nutmeg (Myristicu rylike fruits are generally indehiscent; no frugruns) and, after digesting the aril or hard or tough integument keeps animals mace, casts up the seed uninjured. -

The Diets of Neotropical Trogons, Motmots, Barbets and Toucans

The Condor 95:178-192 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1993 THE DIETS OF NEOTROPICAL TROGONS, MOTMOTS, BARBETS AND TOUCANS J. V. REMSEN, JR., MARY ANN HYDE~ AND ANGELA CHAPMAN Museum of Natural Scienceand Department of Zoology and Physiology, Louisiana State University,Baton Rouge, LA. 70803 Abstract. Although membership in broad diet categoriesis a standardfeature of community analysesof Neotropical birds, the bases for assignmentsto diet categoriesare usually not stated, or they are derived from anecdotal information or bill shape. We used notations of stomachcontents on museum specimenlabels to assessmembership in broad diet categories (“fruit only,” “ arthropods only,” and “fruit and arthropods”) for speciesof four families of birds in the Neotropics usually consideredto have a mixed diet of fruit and animal matter: trogons (Trogonidae), motmots (Momotidae), New World barbets (Capitonidae), and tou- cans (Ramphastidae). An assessmentof the accuracyof label data by direct comparison to independentmicroscopic analysis of actual stomachcontents of the same specimensshowed that label notations were remarkably accurate.The specimen label data for 246 individuals of 17 speciesof Trogonidae showed that quetzals (Pharomachrus)differ significantly from other trogons (Trogon) in being more fiugivorous. Significant differences in degree of fru- givory were found among various Trogonspecies. Within the Trogonidae, degreeof frugivory is strongly correlated with body size, the larger speciesbeing more frugivorous. The more frugivorous quetzals (Pharomachrus)have relatively flatter bills than other trogons, in ac- cordancewith predictions concerningmorphology of frugivores;otherwise, bill morphology correlated poorly with degree of fiugivory. An analysis of label data from 124 individuals of six speciesof motmots showed that one species(Electron platyrhynchum)is highly in- sectivorous,differing significantlyfrom two others that are more frugivorous(Baryphthengus martii and Momotus momota). -

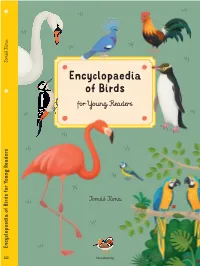

Encyclopaedia of Birds for © Designed by B4U Publishing, Member of Albatros Media Group, 2020

✹ Tomáš Tůma Tomáš ✹ ✹ We all know that there are many birds in the sky, but did you know that there is a similar Encyclopaedia vast number on our planet’s surface? The bird kingdom is weird, wonderful, vivid ✹ of Birds and fascinating. This encyclopaedia will introduce you to over a hundred of the for Young Readers world’s best-known birds, as well as giving you a clear idea of the orders in which birds ✹ ✹ are classified. You will find an attractive selection of birds of prey, parrots, penguins, songbirds and aquatic birds from practically every corner of Planet Earth. The magnificent full-colour illustrations and easy-to-read text make this book a handy guide that every pre- schooler and young schoolchild will enjoy. Tomáš Tůma www.b4upublishing.com Readers Young Encyclopaedia of Birds for © Designed by B4U Publishing, member of Albatros Media Group, 2020. ean + isbn Two pairs of toes, one turned forward, ✹ Toco toucan ✹ Chestnut-eared aracari ✹ Emerald toucanet the other back, are a clear indication that Piciformes spend most of their time in the trees. The beaks of toucans and aracaris The diet of the chestnut-eared The emerald toucanet lives in grow to a remarkable size. Yet aracari consists mainly of the fruit of the mountain forests of South We climb Woodpeckers hold themselves against tree-trunks these beaks are so light, they are no tropical trees. It is found in the forest America, making its nest in the using their firm tail feathers. Also characteristic impediment to the birds’ deft flight lowlands of Amazonia and in the hollow of a tree. -

Sun Parakeet Birding Tour

Leon Moore Nature Experience – Sun Parakeet Birding Tour Guyana is a small English-speaking country located on the Atlantic Coast of South America, east of Venezuela and west of Suriname. Deserving of its reputation as one of the top birding and wildlife destinations in South America, Guyana’s pristine habitats stretch from the protected shell beach and mangrove forest along the northern coast, across the vast untouched rainforest of the interior, to the wide open savannah of the Rupununi in the south. Guyana hosts more than 850 different species of birds covering over 70 families. Perhaps the biggest attraction is the 45+ Guianan Shield endemic species that are more easily seen here than any other country in South America. These sought-after near-endemic species include everything from the ridiculous to the sublime - from the outrageous Capuchinbird with a bizarre voice unlike any other avian species to the unbelievably stunning Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock. While the majestic Harpy Eagle is on everyone’s “must-see” list, other species are not to be overlooked, such as Rufous-throated, White-plumed and Wing-barred Antbirds, Gray-winged Trumpeter, Rufous-winged Ground Cuckoo, Blood-colored Woodpecker, Rufous Crab-Hawk, Guianan Red-Cotinga, White-winged Potoo, Black Curassow, Sun Parakeet, Red Siskin, Rio-Branco Antbird, and the Dusky Purpletuft. These are just a few of the many spectacular birding highlights that can be seen in this amazing country. Not only is Guyana a remarkable birding destination, but it also offers tourists the opportunity to observe many other unique fauna. The elusive Jaguar can sometimes be seen along trails and roadways. -

The Hairy Woodpecker in Central America

THE HAIRY WOODPECKER IN CENTRAL AMERICA BY ALEXANDER F. SKUTCH HE Hairy Woodpecker (Dendrocopos villosus) , familiar to nearly every T observant person who frequents the woods and fields of temperate North America, is found in the highlands of the warmer parts of the con- tinent as far south as western Panama. The forms of the species that breed in the mountains of Central America are distinct from those resident farther north, yet all are so similar in plumage and voice that the naturalist who knows any race of the Hairy Woodpecker will at once greet a member of any other race as an old friend. Only after the first warmth of recognition has passed will he begin to think about the differences between the southern bird and its northern relatives. The Central American forms are smaller than the more boreal forms and have the under parts, and sometimes also the white central band along the back, more or less strongly tinged with brown. In both Guatemala and Costa Rica Hairy Woodpeckers occupy a broad altitudinal belt extending from about 4,000 to at least 11,000 feet above sea-level. At the lowermost of the elevations mentioned they appear to occur only where the mountain slopes are exposed to the prevailing winds and hence unusually cool and humid for the altitude. In the valleys and on the more sheltered slopes they are rarely met lower than 6,000 feet. Near Vara Blanca, on the northern or windward slope of the Cordillera Central of Costa Rica, an excessively humid region exposed to the full sweep of the northeast trade-winds and subject to long-continued storms of wind-driven mist and rain, I found Hairy Woodpeckers abundant at 5,500 feet. -

South East Brazil, 18Th – 27Th January 2018, by Martin Wootton

South East Brazil 18th – 27th January 2018 Grey-winged Cotinga (AF), Pico da Caledonia – rare, range-restricted, difficult to see, Bird of the Trip Introduction This report covers a short trip to South East Brazil staying at Itororó Eco-lodge managed & owned by Rainer Dungs. Andy Foster of Serra Dos Tucanos guided the small group. Itinerary Thursday 18th January • Nightmare of a travel day with the flight leaving Manchester 30 mins late and then only able to land in Amsterdam at the second attempt due to high winds. Quick sprint (stagger!) across Schiphol airport to get onto the Rio flight which then parked on the tarmac for 2 hours due to the winds. Another roller-coaster ride across a turbulent North Atlantic and we finally arrived in Rio De Janeiro two hours late. Eventually managed to get the free shuttle to the Linx Hotel adjacent to airport Friday 19th January • Collected from the Linx by our very punctual driver (this was to be a theme) and 2.5hour transfer to Itororo Lodge through surprisingly light traffic. Birded the White Trail in the afternoon. Saturday 20th January • All day in Duas Barras & Sumidouro area. Luggage arrived. Sunday 21st January • All day at REGUA (Reserva Ecologica de Guapiacu) – wetlands and surrounding lowland forest. Andy was ill so guided by the very capable REGUA guide Adelei. Short visit late pm to Waldanoor Trail for Frilled Coquette & then return to lodge Monday 22nd January • All day around lodge – Blue Trail (am) & White Trail (pm) Tuesday 23rd January • Early start (& finish) at Pico da Caledonia. -

Roosting and Nesting of Aracari Toucans

THE CONDOR VOLUME 60 JULY-AUGUST, 19% NUMBER 4 ROOSTING AND NESTING OF ARACARI TOUCANS By ALEXANDER F. SKUTCH The genus Pteroglossuscontains a number of speciesof toucans of small or medium size to which the name araqari is usually given. The slendernessof body and bill in the Central American representatives of this group is very evident when one compares them with the bulky toucans of the genus Ramphastos which inhabit the same forests. Of the two species of Pteroglossus in the lowlands and foothills of Central America, P. torquatus is of wide distribution, while P. frantzii, far brighter in color, is restricted to the Pacific side of southern Costa Rica and adjoining parts of the republic of Panama. Although these two birds were united in the same speciesby Peters (1948), their differ- ences in coloration are evident at a glance and they do not seem to intergrade. Yet their similarities in voice, habits, size, and color pattern show that they are closely related. Since my studies of these rather elusive birds are incomplete and since there is little information available on their behavior, I shall discuss them in the same paper. Thus gaps in my observations on one species may be filled in a measure by my studies of the other species. COLLARED ARACARI Appearance.-The Collared Aracari (Pteroglossus torquatus) , the duller and more widespread of these two toucans, is a slender bird, whose length of about 16 inches is largely accounted for by its heavy bill and long, graduated tail (fig. 1) . The general tone of the head and most of the upper plumage, including the wings and tail, is black. -

Aazpa Librarians Special Interest Group Bibliography Service

AAZPA LIBRARIANS SPECIAL INTEREST GROUP BIBLIOGRAPHY SERVICE The bibliography is provided as a service of the AAZPA LIBRARIANS SPECIAL INTEREST GROUP and THE CONSORTIUM OF AQUARIUMS, UNIVERSITIES AND ZOOS. TITLE: Toucan Bibliography AUTHOR & INSTITUTION: Mary Healy Discovery Island, Buena Vista, Florida DATE: 1990 Austin, O.A. 1961. Birds of the World. Racine, WI:Western Publishing Co., Inc. Berry, R.J. and B. Coffey. 1976. Breeding the sulphur-breasted toucan, Ramphastos s. sulfuratus at Houston Zoo. International Zoo Yearbook, 16:108-110. Bourne, G.R. 1974. The red-billed toucan in Guyana. Living Bird, 13: 99-126. Brehm, W.W. 1969. Breeding the green-billed toucan, Ramphastos dicolorus at the Walsrode Bird Park. International Zoo Yearbook, 9:134-135. Buhl, K. 1982. Red-breasted toucans flourish in Phoenix. The A.F.A. Watchbird, 9(3):27-28. Campbell, B. 1974. Dictionary of Birds. New York:Exeter Books. Coates-Estrada, R. and A. Estrada. 1986. Fruiting and frugivores at a strangler fig in the tropical rain forest of Los Tuxtlas, Mexico. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 2(4):349-358. Cracraft, J. and R.O. Prum. 1988. Patterns and processes of diversification speciation and historical congruence in neotropical birds. Evolution, 42(3):603-620. Dewald, D.D. 1988. Channel-billed toucans. The A.F.A. Watchbird, 15(1): 36-37. Dhillon, A.S. and D.M. Schaberg. 1984. Pseudotuberculosis in toucans. 73rd Annual Meeting of the Poultry Science Association, Inc. Poultry Science, 63(suppl.1):90. Flesness, N. 1984. ISIS Avian Taxonomy Directory, 2nd ed. Apple Valley, MN:ISIS. Giddings, R.F. 1988.