Revisited. on a Pin from the Bronze Age Site of Shahdad (Kerman, Iran)1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bam, Iran Earthquake of 26 December 2003, Mw6.5: a Study on the Strong Ground Motions

13th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering Vancouver, B.C., Canada August 1-6, 2004 Paper No. 8001 BAM, IRAN EARTHQUAKE OF 26 DECEMBER 2003, MW6.5: A STUDY ON THE STRONG GROUND MOTIONS Mehdi ZARE1 SUMMARY The Bam earthquake of 26 December 2003 (Mw6.5) occurred at 01:56:56 (GMT, 05:26:56 local time) around the city of Bam in the southeast of Iran. The Bam earthquake of 26/12/2003 (Mw6.5) has demolished the city of Bam, having a population of about 100000 at the time of the earthquake. The Bam fault - which was mapped before the event on the geological maps - has been reactivated during the 26/12/2003 earthquake. It seems that a length of about 10km (at the surface) of this fault has been reactivated, where it passed exactly from the east of the city of Bam. The fault has a slop towards the west and the foci of the event was located closed to the residential area (almost beneath the city of Bam). This caused a great damage in the macroseismic epicentral zone; however the strong motions have been attenuated very rapidly, specially towards the east-and west (fault normal) direction. The vertical directivity effects caused the amplification of the low frequency motions in the fault-normal direction as well as the greater amplitude of the motion on the vertical direction. INTRODUCTION The Bam earthquake of 26/12/2003 (Mw6.5) demolished the city of Bam in the southeast of Iran (Figure- 1). The earthquake happened at 5:26 am local time when most of the inhabitants were slept, that can be one of the causes of the great life losses. -

Characteristics of 2017 Hojedk Earthquake Sequence in Kerman Province, Southeast Iran

Revista Geoaraguaia ISSN:2236-9716 Barra do Garças – MT v.10, n. esp. Geologia e Pedologia p.187-201. Dez-2020 CHARACTERISTICS OF 2017 HOJEDK EARTHQUAKE SEQUENCE IN KERMAN PROVINCE, SOUTHEAST IRAN CARACTERÍSTICAS DA SEQUÊNCIA DE TERREMOTO HOJEDK 2017 NA PROVÍNCIA DE KERMAN, SUDESTE DO IRÃ Nassim Mahdavi-Omran1 Mohammad-Reza Gheitanchi2 ABSTRACT Kerman province in southeast Iran, has experienced historical and instrumentally recorded earthquakes. In December 2017, three destructive earthquakes have occurred around Hojedk, in Kerman within 11 days. In this study, first the regional seismotectonics and seismicity is presented. Then, the source mechanisms of main shocks are modeled and the results are compared with the active faults and seismicity pattern is discussed. Moment tensor inversion in time domain is used to obtain the source mechanism of earthquakes. The results indicate that the mechanisms of main shocks and aftershocks are mainly reverse and are in agreement with the trend of tectonic forces as well as the mechanisms of other earthquakes. The epicentral distribution of aftershocks indicates two clusters. The spatial distributions of clusters are in agreement with the epicentral distribution of main shocks. The cluster around the first earthquake in EW cross section has a length 15-20 Km, while the cluster around the second and third has a length about 20-25 Km. The Hojedk earthquakes occurred along the northern extension of previous earthquakes where a kind of seismic gap could be observed and still exists. In 1972, within five days four earthquakes with magnitudes 5.5 to 6.2 occurred in Sefidabeh region in eastern edge of Lut block. -

Bonner Zoologische Beiträge

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Bonn zoological Bulletin - früher Bonner Zoologische Beiträge. Jahr/Year: 1978 Band/Volume: 29 Autor(en)/Author(s): Desfayes M., Praz J. C. Artikel/Article: Notes on Habitat and Distribution of Montane Birds in Southern Iran 18-37 © Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zoologicalbulletin.de; www.biologiezentrum.at Bonn. 18 zool. Beitr. Notes on Habitat and Distribution of Montane Birds in Southern Iran by M. DESFAYES, Washington, and J. C. PRAZ, Sempach This study was carried out in May and June 1975 to fill a gap in our knowledge of the breeding birds, their distribution and ecology, in the mountains of southern Iran. In these two months, most species occupy their breeding territories. Records from April or July are not always reliable as an indication of breeding, even if the bird is observed singing. While the avifauna of the northern parts of the country is relatively well-known, that of the southern highlands (above 2,000 meters) is poorly known. Blanford (1876) collected at Rayen (Rayun) 2100 m, and Hanaka, 2400 m, south-east of Kerman, just east of the Kuh-e Hazar, from 30 April to 2 May, and also at Khan-e Sorkh Pass 2550 m, 115 km south-west of Kerman on 23 May. Species collected in these areas by Blanford are: Columba palum- bus, Cuculus canorus, Melanocorypha bimaculata, Motacilla alba, Lanius collurio, Oenanthe picata, Oe. lugens, Oe. xanthoprymna, Montícola saxa- tilis, Sylvia curruca, Serinus pusillus, Acanthis cannabina, Emberiza bucha- nani, and E. -

Interseismic Slip-Rate of the Kuhbanan-Lakar Kuh Faults System: Using Insar Technique

EH-09260582 INTERSEISMIC SLIP-RATE OF THE KUHBANAN-LAKAR KUH FAULTS SYSTEM: USING INSAR TECHNIQUE Sajjad MOLAVI VARDANJANI M.Sc. Student, Graduate University of Advanced Technology, Kerman, Iran [email protected] Majid SHAHPASANDZADEH Associate Professor, Graduate University of Advanced Technology, Kerman, Iran [email protected] Ali ESMAEILY Assistant Professor, Dept. of Surveying Eng., Graduate University of Advanced Technology, Kerman, Iran [email protected] Mohammad Reza SEPAHVAND Assistant Professor, Graduate University of Advanced Technology, Kerman, Iran [email protected] Saeede KESHAVARZ Assistant Professor, Graduate University of Advanced Technology, Kerman, Iran [email protected] Keywords: Interseismic deformation, Geodetic fault slip-rate, InSAR, Kerman, Kuhbanan-Lakar Kuh fault system The Kuhbanan fault with ~ 300 km length, one of the largest seismogenic faults in the southeast of Iran, has caused st st several catastrophic earthquakes with Ms 5-6.2 in 20 -21 centuries (Table 1). Moreover, the corresponding cross-thrusts were also associated with at least five clusters of medium-magnitude earthquakes. The Lakar Kuh fault with ~160 km length run parallel to the Nayband fault (Figure 1). The slip-rate of faults and also the spatio-temporal distribution of large-magnitude shallow-depth earthquakes on the Kuhbanan-Lakar Kuh fault system, attain broad concern for seismic hazard assessment (Figure 1). The horizontal slip-rate of the Kuhbanan fault is estimated ~1–2 mm/yr (Walker et al., 2012). Furthermore, the total horizontal displacement of the fault is reported ~5–7 km, as determined by the offset geological markers (Table 2). Table 1. -

Coleoptera: Meloidae) in Kerman Province, Iran

J Insect Biodivers Syst 07(1): 1–13 ISSN: 2423-8112 JOURNAL OF INSECT BIODIVERSITY AND SYSTEMATICS Research Article https://jibs.modares.ac.ir http://zoobank.org/References/216741FF-63FB-4DF7-85EB-37F33B1182F2 List of species of blister beetles (Coleoptera: Meloidae) in Kerman province, Iran Sara Sadat Nezhad-Ghaderi1 , Jamasb Nozari1* , Arastoo Badoei Dalfard2 & Vahdi Hosseini Naveh1 1 Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of Tehran, Karaj, Iran. [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman, Kerman, Iran. [email protected] ABSTRACT. The family Meloidae Gyllenhaal, 1810 (Coleoptera), commonly known as blister beetles, exist in warm, dry, and vast habitats. This family was studied in Kerman province of Iran during 2018–2019. The specimens were Received: collected using sweeping net and via hand-catch. They were identified by the 23 December, 2019 morphological characters, genitalia, and acceptable identification keys. To improve the knowledge of the Meloidae species of southeastern Iran, faunistic Accepted: 11 September, 2020 investigations on blister beetles of this region were carried out. Totally, 30 species belonging to 10 genera from two subfamilies (Meloinae and Published: Nemognathinae) were identified. Among the identified specimens, 22 species 14 September, 2020 were new for fauna of Kerman province. Subject Editor: Sayeh Serri Key words: Meloidae, Southeastern Iran, Meloinae, Nemognathinae, Fauna Citation: Nezhad-Ghaderi, S.S., Nozari, J., Badoei Dalfard, A. & Hosseini Naveh, V. (2021) List of species of blister beetles (Coleoptera: Meloidae) in Kerman province, Iran. Journal of Insect Biodiversity and Systematics, 7 (1), 1–13. -

Numerical Investigation of Groundwater Balance and Artificial Recharge in the Kerman-Baghin Aquifer

Journal of Hydraulic Structures J. Hydraul. Struct., 2021; 7(2):1-21 DOI: 10.22055/jhs.2021.36940.1166 Numerical investigation of groundwater balance and artificial recharge in the Kerman-Baghin Aquifer Sina Pakmanesh 1 Mahnaz Ghaeini-Hessaroeyeh 2 Ehsan Fadaei-Kermani 3 Abstract In the present paper, the behavior of Kerman-Baghin aquifer has been investigated using the MODFLOW program and GMS 10.3 software. The piezometer data during October 2011 are applied for steady state condition of groundwater modeling. Then, the model is calibrated for 66 months for unsteady condition using observational information, and it is validated for 24 months. Finally, the results are compared with the available observed data and show acceptable accuracy in calibration and validation steps. After validating the model, the status of the aquifer is estimated for a period of 5 years. Management scenarios including 10, 20 and 30 percent reduction in groundwater abstraction as well as artificial recharge at eight selected aquifer sites have been investigated. The location of artificial recharge sites is selected based on seven parameters of land slope, distance from waterways, distance from faults, electrical conductivity, hydraulic conductivity, geology of the area and groundwater depth (thickness of unsaturated area). These parameters are combined with the index overlay method by Arc GIS 10.3 software. The results show that by continuing the current situation, the Kerman-Baghin aquifer could face an average annual deficit of more than 52 million cubic meters. It may cause various problems in the near future including abstraction water from groundwater sources and reducing water quality. The results of implementing different scenarios show that, the best scenario can be obtained by 10% reducing water withdrawal with artificial recharge in four zones 1, 2, 10 and 12. -

Of SE Iranian Mountains Exemplified by the Kuh-I-Jupar, Kuh-I-Lalezar and Kuh-I-Hezar Massifs in the Zagros

Umbruch 77.2-3 09.12.2008 15:43 Uhr Seite 71 Polarforschung 77 (2-3), 71 – 88, 2007 (erschienen 2008) The Pleistocene Glaciation (LGP and pre-LGP, pre-LGM) of SE Iranian Mountains Exemplified by the Kuh-i-Jupar, Kuh-i-Lalezar and Kuh-i-Hezar Massifs in the Zagros by Matthias Kuhle1 Abstract: Evidence has been provided of two mountain glaciations in the tion the Kuh-i-Lalezar massif (4374 m, 29°23'28.01" N 4135 m high, currently non-glaciated Kuh-i-Jupar massif in the semi-arid 56°44'49.38" E) has been visited in April and May 1973. The Zagros: an older period during the pre-LGP (Riss glaciation, c. 130 Ka) and a younger one during the LGP (Würm glaciation, Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) results attained by Quaternary geological and geomorpholo- 4-2: 60-18 Ka). During the pre-LGP glaciation the glaciers reached a gical methods stand in contrast to earlier assumptions concern- maximum of 17 km in length; during the LGP glaciation they were 10-12 km ing the former glaciation of these semi-arid Iranian mountains. long. They flowed down into the mountain foreland as far as 2160 m (LGP glaciation) and 1900 m (pre-LGP glaciation). The thickness of the valley Parts – Kuh-i-Jupar massif – were already published in glaciers reached 550 (pre-LGP glaciation) and 350 m (LGP glaciation). German. They are included in this paper in a summarized During the pre-LGP a 23 km-wide continuous piedmont glacier lobe devel- form. In continuation of these results new observations from oped parallel to the mountain foot. -

Kerman Province)

Quaderni del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Ferrara - Vol. 7 - 2019 - pp. 27-35 ISSN 2283-6918 Contribution to the knowledge of Iranian flora: a herborization in the Dasht-e-Lut area (Kerman Province) LORENZO CECCHI Università degli Studi di Firenze, Sistema Museale di Ateneo, Museo di Storia Naturale, Collezioni di Botanica - Via Giorgio La Pira 4 - Florence (Italy); E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A joined research project named “Meteorites and plants from Lut desert” was performed in 2017 by the Botanical and Mineralogical sections of Natural History Museum of Florence with other Italian and Iranian partners. It enabled the collection of 146 plant specimens in SE Iran. It’s a small but rather rare and significant contribution to the knowledge of a very remote and poorly known region of central Asia, including both important endemics and characteristic species of steppic and desertic environments. Keywords: Iranian flora, Dasht-e-Lut area, Kerman Province. Riassunto Contributo alla conoscenza floristica dell’Iran: un’erborizzazione nell’area del deserto di Lut (Provincia di Kerman) Il progetto di ricerca congiunto “Meteorites and plants from Lut desert”, condotto dalle sezioni di Botanica e Mineralogia del Museo di Storia Naturale di Firenze in collaborazione con rappresentanti di altre istituzioni sia italiane che iraniane, ha permesso la raccolta di 146 campioni vegetali nell’Iran sud-orientale. Si tratta di un modesto ma raro e significativo contributo alla conoscenza di una regione particolarmente remota e poco conosciuta dell’Asia centrale, che comprende importanti endemismi e specie caratteristiche di ambienti steppici e desertico. Parole chiave: Flora iraniana, Area di Dasht-e-Lut, provincia di Kerman. -

Sexual Dimorphism in a New Species of Cassiduloid Echinoid, Pygaulus Baghinensis, from the Aptian Strata of Baghin Area, West of Kerman, Iran

Journal of Sciences, Islamic Republic of Iran 21(1): 43-47 (2010) http://jsciences.ut.ac.ir University of Tehran, ISSN 1016-1104 Sexual Dimorphism in a New Species of Cassiduloid Echinoid, Pygaulus baghinensis, from the Aptian Strata of Baghin Area, West of Kerman, Iran * A.L. Arab and M.R. Vaziri Department of Geology, Faculty of Sciences, Shahid Bahonar University, Kerman, Islamic Republic of Iran Received: 25 January 2009 / Revised: 5 August 2009 / Accepted: 30 September 2009 Abstract A new species of cassiduloid echinoids, Pygaulus baghinensis is reported for the first time from Aptian sediments of Baghin area, west of Kerman, Iran. The diagnostic features of the species are centrally positioned of the apical disc and approximately low profile of the test. Variation in gonopore size in different individuals allows to conclude that P. baghinensis is sexually dimorphic. Specimens with large gonopores can be considered to be females, while other specimens whose gonopores diameter is small, can be considered to be males. One of the specimens has one large and three small gonopores on its apical disc. This difference may be due to hermaphroditic feature of the specimen. Keywords: Sexual dimorphism; Gonopore; Cassiduloid echinoids; Cretaceous; Iran distinguished. Sexual dimorphism among cassiduloids is Introduction exceptional. Saucede and Neraudeau [15] have reported Sexual dimorphism is common in recent echinoids. sexual dimorphism in a cassiduloid echinoid, Nucleo- Males and females are almost always separate from pygus (Jolyclypus) jolyi in Cenomanian strata, based on each other and seldom indicate pronounced sexual gonopores size. dimorphism [5]. Individuals with large gonopores can This paper deals with the first example of be considered to be females [4,8,14,16]. -

Kerman Province

In TheGod Name of Kerman Ganjali khan water reservoir / Contents: Subject page Kerman Province/11 Mount Hezar / 11 Mount joopar/11 Kerman city / 11 Ganjalikhan square / 11 Ganjalikhan bazaar/11 Ganjalikhan public bath /12 Ganjalikhan Mint house/12 Ganjalikhan School/12 Ganjalikhan Mosque /13 Ganjalikhan Cross market place /13 Alimardan Khan water reservoir /13 Ibrahimkhan complex/ 13 Ibrahimkhan Bazaar/14 Ibrahimkhan School /14 Ibrahimkhan bath/14 Vakil Complex/14 Vakil public bath / 14 Vakil Bazaar / 16 Vakil Caravansary / 16 Hajagha Ali complex / 16 Hajagha Ali mosque / 17 Hajagha Ali bazaar / 17 Hajagha Ali reservoir / 17 Bazaar Complex / 17 Arg- Square bazaar / 18 Kerman Throughout bazaar / 18 North Copper Smithing bazaar / 18 Arg bazaar / 18 West coppersmithing bazaar / 18 Ekhteyari bazaar / 18 Mozaffari bazaar / 19 Indian Caravansary / 19 Golshan house / 19 Mozaffari grand mosque / 19 Imam mosque / 20 Moshtaghieh / 20 Green Dome / 20 Jebalieh Dome / 21 Shah Namatollah threshold / 21 Khaje Etabak tomb / 23 Imam zadeh shahzadeh Hossien tomb / 23 Imam zadeh shahzadeh Mohammad / 23 Qaleh Dokhtar / 23 Kerman fire temple / 24 Moaidi Ice house / 24 Kerman national library / 25 Gholibig throne palace / 25 Fathabad Garden / 25 Shotor Galoo / 25 Shah zadeh garden / 26 Harandi garden / 26 Arg-e Rayen / 26 Ganjalikhan anthropology museum / 27 Coin museum / 27 Harandi museum garden / 27 Sanatti museum / 28 Zoroasterian museum / 28 Shahid Bahonar museum / 28 Holy defense museum / 28 Jebalieh museum / 29 Shah Namatollah dome museum / 29 Ghaem wooden -

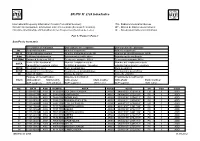

BR IFIC N° 2728 Index/Indice

BR IFIC N° 2728 Index/Indice International Frequency Information Circular (Terrestrial Services) ITU - Radiocommunication Bureau Circular Internacional de Información sobre Frecuencias (Servicios Terrenales) UIT - Oficina de Radiocomunicaciones Circulaire Internationale d'Information sur les Fréquences (Services de Terre) UIT - Bureau des Radiocommunications Part 1 / Partie 1 / Parte 1 Date/Fecha 18.09.2012 Description of Columns Description des colonnes Descripción de columnas No. Sequential number Numéro séquenciel Número sequencial BR Id. BR identification number Numéro d'identification du BR Número de identificación de la BR Adm Notifying Administration Administration notificatrice Administración notificante 1A [MHz] Assigned frequency [MHz] Fréquence assignée [MHz] Frecuencia asignada [MHz] Name of the location of Nom de l'emplacement de Nombre del emplazamiento de 4A/5A transmitting / receiving station la station d'émission / réception estación transmisora / receptora 4B/5B Geographical area Zone géographique Zona geográfica 4C/5C Geographical coordinates Coordonnées géographiques Coordenadas geográficas 6A Class of station Classe de station Clase de estación Purpose of the notification: Objet de la notification: Propósito de la notificación: Intent ADD-addition MOD-modify ADD-ajouter MOD-modifier ADD-añadir MOD-modificar SUP-suppress W/D-withdraw SUP-supprimer W/D-retirer SUP-suprimir W/D-retirar No. BR Id Adm 1A [MHz] 4A/5A 4B/5B 4C/5C 6A Part Intent 1 112143773 ARG 7135.0000 COLONIA AURORA ARG 54W30'53'' 27S28'19'' FX 1 ADD 2 -

Destructive Effects of the 2003 Bam Earthquake on Structures

ASIAN JOURNAL OF CIVIL ENGINEERING (BUILDING AND HOUSING) VOL. 8, NO. 3 (2007) PAGES 329-342 DESTRUCTIVE EFFECTS OF THE 2003 BAM EARTHQUAKE ON STRUCTURES S.M. Zahrai∗ and M. Heidarzadeh Center of Excellence in infrastructural Engineering and Management, School of Civil Engineering, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran ABSTRACT On 26 December 2003 at 1:57 GMT, the historical city of Bam, located in the south-eastern region of Kerman province in Iran, was shaken by a relatively strong and destructive o o earthquake. The earthquake located at 29.0 N and 58.26 W had a Mb of 6.3 by Geophysics Institute of the University of Tehran and an Ms of 6.5 estimated by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). The main shock killed nearly 35000 people, left more than 50000 homeless, and destroyed virtually all buildings in the region. Based on the reconnaissance visit by the authors, most common types of damaged buildings in the earthquake-affected area were non-engineered adobe, un-reinforced masonry houses and steel buildings. Most houses in the epicentral area were of adobe construction, made of sun dried clay brick walls, and heavy domestic roofs or vaults with clay or mud mortar. This earthquake clearly demonstrated that combination of relatively rigid load-bearing external brick walls and flexible internal steel columns, existing similarly in most other regions of the country, is quite hazardous. Also use of steel beams and columns in buildings without observing proper seismic provisions showed no improvement over non-engineered buildings. Unlike Some researchers who claimed that the performance of reinforced concrete structures in the area was satisfactory, probably due to the fact that the number of the reinforced concrete structures in the stricken area was for less than the other type of structures, authors believe that it was not so better than others.