Scotland, the UK and Brexit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stewart2019.Pdf

Political Change and Scottish Nationalism in Dundee 1973-2012 Thomas A W Stewart PhD Thesis University of Edinburgh 2019 Abstract Prior to the 2014 independence referendum, the Scottish National Party’s strongest bastions of support were in rural areas. The sole exception was Dundee, where it has consistently enjoyed levels of support well ahead of the national average, first replacing the Conservatives as the city’s second party in the 1970s before overcoming Labour to become its leading force in the 2000s. Through this period it achieved Westminster representation between 1974 and 1987, and again since 2005, and had won both of its Scottish Parliamentary seats by 2007. This performance has been completely unmatched in any of the country’s other cities. Using a mixture of archival research, oral history interviews, the local press and memoires, this thesis seeks to explain the party’s record of success in Dundee. It will assess the extent to which the character of the city itself, its economy, demography, geography, history, and local media landscape, made Dundee especially prone to Nationalist politics. It will then address the more fundamental importance of the interaction of local political forces that were independent of the city’s nature through an examination of the ability of party machines, key individuals and political strategies to shape the city’s electoral landscape. The local SNP and its main rival throughout the period, the Labour Party, will be analysed in particular detail. The thesis will also take time to delve into the histories of the Conservatives, Liberals and Radical Left within the city and their influence on the fortunes of the SNP. -

The Political Myth of Margaret Thatcher in Scotland

Polish Political Science Yearbook vol. 45 (2016), pp. 85–98 DOI: 10.15804/ppsy2016007 PL ISSN 0208-7375 Tomasz Czapiewski University of Szczecin (Poland) The Political Myth of Margaret Thatcher in Scotland Abstract: The article describes and explains the phenomenon of the politi- cal myth of Margaret Thatcher – her anti-Scottish attitude and policies and its impact on the process of decomposition of the United Kingdom. The author indicates that the view of Margaret Thatcher’s dominance in Scotland is simpli- fied, stripped of complexity, ignoring significant information conflicting with the thesis, but that also plays an important role in current politics, legitimizing seces- sionist demands and strengthening the identity of the Scottish community. In the contemporary Scottish debate with its unequivocal defence policy of Thatcher is outside of the discourse, proving its sanctity status. Thatcher could see this special Scottish dimension within the United Kingdom, but treated it rather as a delay in the reforms needed in the country. There are many counterarguments to the validity of the Thatcher myth. Firstly, many negative processes that took place in the 80s were not initiated by Thatcher, only accelerated. Secondly, the Tory decline in popularity in the north began before the leadership of Thatcher and has lasted long after her dismissal. The Conservative Party was permanently seen in Scotland as openly English. Thirdly, there is a lot of accuracy in the opinion that the real division is not between Scotland and England, only between south- ern England and the rest of the country. Widespread opinion that Thatcher was hostile to Scotland is to a large extent untruthful. -

Breaking out of Britain's Neo-Liberal State

cDIREoCTIONmFOR THE pass DEMOCRATIC LEFT Breaking out of Britain’s Neo-Liberal State January 2009 Gerry Hassan and Anthony Barnett 3 4 r Tr hink e b m m u N PIECES 3 4 Tr hink e b m u N PIECES Breaking out of Britain’s Neo-Liberal State Gerry Hassan and Anthony Barnett “In the big-dipper of UK politics, the financial crisis suddenly re-reversed these terms. Gordon Brown excavated a belief in Keynesian solutions from his social democratic past and a solidity of purpose that was lacking from Blair’s lightness of being” Compass publications are intended to create real debate and discussion around the key issues facing the democratic left - however the views expressed in this publication are not a statement of Compass policy. Breaking out of Britain’s Neo-Liberal State www.compassonline.org.uk PAGE 1 Breaking out of Britain’s reduced for so many, is under threat with The British Empire State Building Neo-Liberal State no state provisions in place for them. The political and even military consequences England’s “Glorious Revolution” of 1688 Gerry Hassan and Anthony Barnett could well be dire. created a framework of compromise between monarchy and Parliament. It was Nonetheless we should celebrate the followed by the union of England with possible defeat of one aspect of neo- Scotland of 1707, which joined two he world we have lived in, liberal domination. It cheered the different countries while preserving their created from the twin oil-price destruction of a communist world that distinct legal traditions. Since then the T shockwaves of 1973 and 1979 was oppressive and unfree. -

ELECTING the FIRST PARLIAMENT Party Competition and Voter Participation in Scotland

PARTY POLITICS VOL 10. No.2 pp. 213–233 Copyright © 2004 SAGE Publications London Thousand Oaks New Delhi www.sagepublications.com ELECTING THE FIRST PARLIAMENT Party Competition and Voter Participation in Scotland Steven E. Galatas ABSTRACT Theory regarding turnout in elections suggests that voters are more likely to vote when their vote could be decisive. The article provides a generalized test of the relationship between the likelihood of turning out and the closeness of elections. Data are single-member district (first- past-the-post) and regional (party list) constituency-level results from the Scottish Parliament election of 1999. Scotland provides an excellent case because the 1999 Scottish Parliament was elected using a combi- nation of single-member districts, plus an additional member, regional list alternative vote system. In addition, the Scottish Parliament election was characterized by regional, multiparty competition. Controlling for other factors, the article finds that closeness counts and relates to higher levels of voter participation in the Scottish Parliament elections. This finding holds for single-member district (first-past-the-post) constituen- cies and additional member regional lists. KEY WORDS electoral competition Scottish Parliament voter turnout In 1999, Scottish voters went to the polls for the first time to elect a Scottish Parliament. Although Scotland had a legislative body prior to the Treaty of Union of 1707, the new Parliament created in 1999 was the first democrat- ically elected Scottish Parliament. Elections to the Scottish Parliament featured a deviation from the single-member district-plurality system (SMD-P) familiar to Scottish voters from other electoral contests. Instead, voters selected Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) using an additional member system (AMS). -

A Wee Bit Different: Socio-Cultural Influences on Scottish Marketing

Published in: Christiane Eisenberg, Rita Gerlach and Christian Handke (eds.). Cultural Industries: The British Experience in International Perspective. 2006. Online. Humboldt University Berlin, Edoc- Server. Available: http://edoc.hu-berlin.de. ISBN 978-3-86004-203-8. A Wee Bit Different: Socio-Cultural Influences on Scottish Marketing Annika Wingbermühle Faculty of Art, University of Passau [email protected] Has the world become the ultimate marketplace? Not really, because resurging nationalism in many European countries indicates that globalisation has still failed to create complete cultural homogeneity. The convergence thesis in cross-cultural marketing therefore appears to be wrong because consumers remain highly susceptible to stimuli that fit their cultural expectations (De Mooij). However, culture as a “whole way of life” (Williams 122) offers predictable social interactions in a post-modern world. Scotland and its quest for an independent identity in particular is a perfect exhibit for this observation. In this country conventional sociological and economic categories turn out to be too wieldy. Therefore, culture is particularly promising as an analytical approach. This paper analyses how cultural differences influence the way the creative industries work. The analysis is based on various works of David McCrone (“Being British”; Understanding Scotland), McCrone et al. (“Who Are We?”), Murray Pittock (Scottish Nationality) and Gerry Hassan (“Anatomy”; “Tales”). Main players in Scottish marketing were interviewed about their views in March 2005. The Scottish trade magazine The Drum offered further insights into the industry. Finally, campaigns were analysed to find out whether or not a ‘Scottish approach’ in marketing exists. All samples are reproduced with kind permission and copyrights remain with the designers. -

Course Document

SCHOOL OF DIVINITY, HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY ACADEMIC SESSION 2018-2019 HI306T PEOPLE POWER: NEW SOCIAL MOVEMENTS IN POST-WAR SCOTLAND 30 CREDITS: 11 WEEKS PLEASE NOTE CAREFULLY: The full set of school regulations and procedures is contained in the Undergraduate Student Handbook which is available online at your MyAberdeen Organisation page. Students are expected to familiarise themselves not only with the contents of this leaflet but also with the contents of the Handbook. Therefore, ignorance of the contents of the Handbook will not excuse the breach of any School regulation or procedure. You must familiarise yourself with this important information at the earliest opportunity. COURSE CO-ORDINATOR Dr Alex Campsie Crombie Annexe 108 Email: [email protected] Tel: 01224-272460 Office Hours: Wednesdays 10am-12pm Discipline Administration: Mrs Barbara McGillivray/Mrs Gillian Brown 50-52 College Bounds 2019 Room CBLG01 - 01224 272199/272454 2018 | [email protected] - Course Document 1 TIMETABLE For time and place of classes, please see MyAberdeen Students can view their university timetable at http://www.abdn.ac.uk/infohub/study/timetables-550.php COURSE DESCRIPTION The last few years have catapulted mass politics to the fore of public consciousness. The Labour Party has seemingly reinvigorated itself by returning to its roots as a ‘social movement’; during the EU referendum Leave activists utilized – to varying degrees of legality – social media to engage large- scale networks of voters; and in Scotland the Yes campaign prided itself on harnessing people power in a way that other mainstream UK parties could not. But this is nothing new. -

20 Years of the Scottish Parliament

SPICe Briefing Pàipear-ullachaidh SPICe 20 Years of the Scottish Parliament David Torrance (House of Commons Library) and Sarah Atherton (SPICe Research) This is a special briefing to mark the 20th anniversary of the Scottish Parliament. This briefing provides an overview of the path to devolution; the work of the Parliament to date, and considers what may be next for the Scottish Parliament. 27 June 2019 SB 19-46 20 Years of the Scottish Parliament, SB 19-46 Contents The road to devolution ___________________________________________________4 Session 1: 1999-2003 ____________________________________________________6 Central themes of Session 1 ______________________________________________7 Party political highlights __________________________________________________7 Key legislation _________________________________________________________8 Further information______________________________________________________8 Session 2: 2003-2007 ____________________________________________________9 Central themes of Session 2 _____________________________________________10 Party political highlights _________________________________________________10 Key legislation ________________________________________________________ 11 Further information_____________________________________________________ 11 Session 3: 2007-2011____________________________________________________12 Central themes of Session 3 _____________________________________________13 Party political highlights _________________________________________________15 Key legislation ________________________________________________________16 -

University of Dundee Yes Or No? Older People, Politics and The

University of Dundee Yes or No? Older people, politics and the Scottish Referendum in 2014 Crowther, Jim; Boeren, Ellen; Mackie, Alan Published in: Research on Ageing and Social Policy DOI: 10.17583/rasp.2018.3095 Publication date: 2018 Licence: CC BY Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Crowther, J., Boeren, E., & Mackie, A. (2018). Yes or No? Older people, politics and the Scottish Referendum in 2014. Research on Ageing and Social Policy, 6(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.17583/rasp.2018.3095 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Instructions for authors, subscriptions and further details: http://rasp.hipatiapress.com Yes or No? Older People, Politics and the Scottish Referendum in 2014 Jim Crowther1, Ellen Boeren1, & Alan Mackie1 1) University of Edinburgh. -

Exploring Twenty Years of Scotland's Journey, Stories and Politics

INTRODUCTION Back to the Future: Exploring Twenty Years of Scotland’s Journey, Stories and Politics Gerry Hassan The Scottish Parliament marked its twentieth anniversary in 2019 – its first elections took place on 6 May 1999, its first session on 12 May 1999, and the formal transfer of powers from Westminster to Scotland on 1 July 1999. Several timeframes led up to this: a more-than-a-century-long campaign for Scottish home rule which dated back to Gladstonian home rule and Keir Hardie’s Independent Labour Party in the 1880s; the more recent post-war attempt to progress constitutional change and self-government which accelerated after the SNP began to become a serious electoral force from the late 1960s onwards; and finally, the shorter period which encapsulated Labour’s preparation for office pre-1997, followed by the relatively smooth last phase of 1997–99 legislating and preparing for a Scottish Parliament. These three phases are all interlinked and overlap, and are part of a bigger picture of negotiating Scotland’s place in relation to the Union, and its autonomy, distinctiveness and voice. Twenty years in historical terms is a relatively short period of time but in terms of politics and political development it is a sizeable period where many of the events now seem part of contemporary history and can often only be described in such a way. This introduc- tion addresses the wider context of the past 20 years, the key ideas and drivers, what devolution was in the beginning of this period, what it aimed to do, and how it – and the Scottish Parliament – are portrayed two decades on. -

Scottish Independence

Published by: The Irish Times Limited (Irish Times Books) © The Irish Times 2014. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of The Irish Times Limited, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographic rights organisation or as expressly permitted by law. Acknowledgements A large thank you to all the authors who have contributed to this book: Mark Hennessey, Patryck Smyth, Martin Mansergh, Arthur Aughey, Gerry Hassan, Chris Johns, Arthur Beesley, Dorcha Lee, Peter Geoghegan, Alex Massie, Eamonn McCann, Paul Gillespie, Gerry Moriarty, Colm Keena, Chris Johns, Fintan O’Toole, Paddy Woodworth, Sarah Gilmartin, Suzanne Lynch, Mary Minihan and Diarmaid Ferriter. Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... 3 Foreword .................................................................................................................................... 7 Scottish Referendum Countdown Begins .................................................................................. 8 ‘I’m voting “Aye”, notionally, reservations notwithstanding’ ................................................ 10 Scottish fight for independence stretches back seven centuries in Bannockburn .................... 12 ‘This is our last and only chance of creating something better’ .............................................. 14 Ireland can adapt -

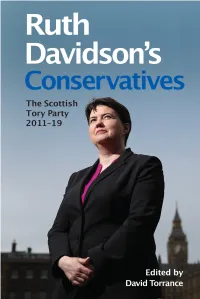

Ruth Davidson's Conservatives

Ruth Davidson’s Conservatives 66343_Torrance.indd343_Torrance.indd i 118/05/208/05/20 33:06:06 PPMM 66343_Torrance.indd343_Torrance.indd iiii 118/05/208/05/20 33:06:06 PPMM Ruth Davidson’s Conservatives The Scottish Tory Party, 2011–19 Edited by DAVID TORRANCE 66343_Torrance.indd343_Torrance.indd iiiiii 118/05/208/05/20 33:06:06 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © editorial matter and organisation David Torrance, 2020 © the chapters their several authors, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road, 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry, Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 10/13 Giovanni by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain. A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5562 6 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5563 3 (paperback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5564 0 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5565 7 (epub) The right of David Torrance to be identifi ed as the editor of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 66343_Torrance.indd343_Torrance.indd iivv 118/05/208/05/20 33:06:06 PPMM CONTENTS List of Tables / vii Notes on the Contributors -

The 79 Group: from Black Sheep to Leadership of The

The 79 Group: From Black Sheep to Leadership of the Scottish National Party Ideological Identity and Legacy in terms of Ideas and People of the 79 Group for the Scottish National Party By Cécile Beauvois Supervisor: Atle L. Wold 30 ECTS A Master’s Thesis submitted to the Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages, Faculty of Humanities UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2019 2 The 79 Group: From Back Sheep to Leadership of the Scottish National Party Ideological Identity and Legacy in terms of Ideas and People of the 79 Group for the Scottish National Party By Cécile Beauvois Supervisor: Atle L. Wold 3 © Cécile Beauvois 2019 The 79 Group: From Black Sheep to Leadership of the Scottish National Party – Ideological Identity and Legacy in terms of Ideas and People of the 79 Group for the Scottish National Party https://www.duo.uio.no/ Print: Reprosentralen, University of Oslo 4 Abstract This thesis has explored the identity and legacy that the 79 Group left to the Scottish National Party. The 79 Group was an organization created within the SNP in the aftermath of the Devolution Referendum held in Scotland on 1 March 1979. In order to determine what legacy the 79 Group left, it was first necessary to establish the ideological portrait of the Group, what it stood for, what were its ideas, policies and ideologies. Although the 79 Group put forward three main principles: nationalism, socialism and republicanism, it also developed many other ideas and modes of action. The 79 Group took some of the themes introduced in the 1970s by the SNP and amplified them, for instance, unemployment which became one of the main arguments the Group used in order to illustrate its case for independence.