Development of Chemoinformatic Tools to Enumerate Functional Groups in Molecules for Organic Aerosol Characterization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Names for Selected Aromatic Groups

More Nomenclature: Common Names for Selected Aromatic Groups Phenyl group = or Ph = C6H5 = Aryl = Ar = aromatic group. It is a broad term, and includes any aromatic rings. Benzyl = Bn = It has a -CH2- (methylene) group attached to the benzene ring. This group can be used to name particular compounds, such as the one shown below. This compound has chlorine attached to a benzyl group, therefore it is called benzyl chloride. Benzoyl = Bz = . This is different from benzyl group (there is an extra “o” in the name). It has a carbonyl attached to the benzene ring instead of a methylene group. For example, is named benzoyl chloride. Therefore, it is sometimes helpful to recognize a common structure in order to name a compound. Example: Nomenclature: 3-phenylpentane Example: This is Amaize. It is used to enhance the yield of corn production. The systematic name for this compound is 2,4-dinitro-6-(1-methylpropyl)phenol. Polynuclear Aromatic Compounds Aromatic rings can fuse together to form polynuclear aromatic compounds. Example: It is two benzene rings fused together, and it is aromatic. The electrons are delocalized in both rings (think about all of its resonance form). Example: This compound is also aromatic, including the ring in the middle. All carbons are sp2 hybridized and the electron density is shared across all 5 rings. Example: DDT is an insecticide and helped to wipe out malaria in many parts of the world. Consequently, the person who discovered it (Muller) won the Nobel Prize in 1942. The systematic name for this compound is 1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis-(4-chlorophenyl)ethane. -

Wannier90 As a Community Code: New

IOP Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter J. Phys.: Condens. Matter J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 32 (2020) 165902 (25pp) https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648X/ab51ff 32 Wannier90 as a community code: new 2020 features and applications © 2020 IOP Publishing Ltd Giovanni Pizzi1,29,30 , Valerio Vitale2,3,29 , Ryotaro Arita4,5 , Stefan Bl gel6 , Frank Freimuth6 , Guillaume G ranton6 , JCOMEL ü é Marco Gibertini1,7 , Dominik Gresch8 , Charles Johnson9 , Takashi Koretsune10,11 , Julen Ibañez-Azpiroz12 , Hyungjun Lee13,14 , 165902 Jae-Mo Lihm15 , Daniel Marchand16 , Antimo Marrazzo1 , Yuriy Mokrousov6,17 , Jamal I Mustafa18 , Yoshiro Nohara19 , 4 20 21 G Pizzi et al Yusuke Nomura , Lorenzo Paulatto , Samuel Poncé , Thomas Ponweiser22 , Junfeng Qiao23 , Florian Thöle24 , Stepan S Tsirkin12,25 , Małgorzata Wierzbowska26 , Nicola Marzari1,29 , Wannier90 as a community code: new features and applications David Vanderbilt27,29 , Ivo Souza12,28,29 , Arash A Mostofi3,29 and Jonathan R Yates21,29 Printed in the UK 1 Theory and Simulation of Materials (THEOS) and National Centre for Computational Design and Discovery of Novel Materials (MARVEL), École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), CH-1015 CM Lausanne, Switzerland 2 Cavendish Laboratory, Department of Physics, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 0HE, United Kingdom 10.1088/1361-648X/ab51ff 3 Departments of Materials and Physics, and the Thomas Young Centre for Theory and Simulation of Materials, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, United Kingdom 4 RIKEN -

De Novo Biosynthesis of Terminal Alkyne-Labeled Natural Products

De novo biosynthesis of terminal alkyne-labeled natural products Xuejun Zhu1,2, Joyce Liu2,3, Wenjun Zhang1,2,4* 1Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, 2Energy Biosciences Institute, 3Department of Bioengineering, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. 4Physical Biosciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. *e-mail:[email protected] 1 Abstract: The terminal alkyne is a functionality widely used in organic synthesis, pharmaceutical science, material science, and bioorthogonal chemistry. This functionality is also found in acetylenic natural products, but the underlying biosynthetic pathways for its formation are not well understood. Here we report the characterization of the first carrier protein- dependent terminal alkyne biosynthetic machinery in microbes. We further demonstrate that this enzymatic machinery can be exploited for the in situ generation and incorporation of terminal alkynes into two natural product scaffolds in E. coli. These results highlight the prospect for tagging major classes of natural products, including polyketides and polyketide/non-ribosomal peptide hybrids, using biosynthetic pathway engineering. 2 Natural products are important small molecules widely used as drugs, pesticides, herbicides, and biological probes. Tagging natural products with a unique chemical handle enables the visualization, enrichment, quantification, and mode of action study of natural products through bioorthogonal chemistry1-4. One prevalent bioorthogonal reaction is -

Phospholipid:Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase: an Enzyme That Catalyzes the Acyl-Coa-Independent Formation of Triacylglycerol in Yeast and Plants

Phospholipid:diacylglycerol acyltransferase: An enzyme that catalyzes the acyl-CoA-independent formation of triacylglycerol in yeast and plants Anders Dahlqvist*†‡, Ulf Ståhl†§, Marit Lenman*, Antoni Banas*, Michael Lee*, Line Sandager¶, Hans Ronne§, and Sten Stymne¶ *Scandinavian Biotechnology Research (ScanBi) AB, Herman Ehles Va¨g 2 S-26831 Svaloˆv, Sweden; ¶Department of Plant Breeding Research, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Herman Ehles va¨g 2–4, S-268 31 Svalo¨v, Sweden; and §Department of Plant Biology, Uppsala Genetic Center, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Box 7080, S-750 07 Uppsala, Sweden Edited by Christopher R. Somerville, Carnegie Institution of Washington, Stanford, CA, and approved March 31, 2000 (received for review February 15, 2000) Triacylglycerol (TAG) is known to be synthesized in a reaction that acid) and epoxidated fatty acid (vernolic acid) in TAG in castor uses acyl-CoA as acyl donor and diacylglycerol (DAG) as acceptor, bean (Ricinus communis) and the hawk’s-beard Crepis palaestina, and which is catalyzed by the enzyme acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol respectively. Furthermore, a similar enzyme is shown to be acyltransferase. We have found that some plants and yeast also present in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and the gene have an acyl-CoA-independent mechanism for TAG synthesis, encoding this enzyme, YNR008w, is identified. which uses phospholipids as acyl donors and DAG as acceptor. This reaction is catalyzed by an enzyme that we call phospholipid:dia- Materials and Methods cylglycerol acyltransferase, or PDAT. PDAT was characterized in Yeast Strains and Plasmids. The wild-type yeast strains used were microsomal preparations from three different oil seeds: sunflower, either FY1679 (MAT␣ his3-⌬200 leu2-⌬1 trp1-⌬6 ura3-52) (9) or castor bean, and Crepis palaestina. -

Accelerating Molecular Docking by Parallelized Heterogeneous Computing – a Case Study of Performance, Quality of Results

solis vasquez, leonardo ACCELERATINGMOLECULARDOCKINGBY PARALLELIZEDHETEROGENEOUSCOMPUTING–A CASESTUDYOFPERFORMANCE,QUALITYOF RESULTS,ANDENERGY-EFFICIENCYUSINGCPUS, GPUS,ANDFPGAS Printed and/or published with the support of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). ACCELERATINGMOLECULARDOCKINGBYPARALLELIZED HETEROGENEOUSCOMPUTING–ACASESTUDYOF PERFORMANCE,QUALITYOFRESULTS,AND ENERGY-EFFICIENCYUSINGCPUS,GPUS,ANDFPGAS at the Computer Science Department of the Technische Universität Darmstadt submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Engineering (Dr.-Ing.) Doctoral thesis by Solis Vasquez, Leonardo from Lima, Peru Reviewers Prof. Dr.-Ing. Andreas Koch Prof. Dr. Christian Plessl Date of the oral exam October 14, 2019 Darmstadt, 2019 D 17 Solis Vasquez, Leonardo: Accelerating Molecular Docking by Parallelized Heterogeneous Computing – A Case Study of Performance, Quality of Re- sults, and Energy-Efficiency using CPUs, GPUs, and FPGAs Darmstadt, Technische Universität Darmstadt Date of the oral exam: October 14, 2019 Please cite this work as: URN: urn:nbn:de:tuda-tuprints-92886 URL: https://tuprints.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/id/eprint/9288 This document is provided by TUprints, The Publication Service of the Technische Universität Darmstadt https://tuprints.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de This work is licensed under a Creative Commons “Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 In- ternational” license. ERKLÄRUNGENLAUTPROMOTIONSORDNUNG §8 Abs. 1 lit. c PromO Ich versichere hiermit, dass die elektronische Version meiner Disserta- tion mit der schriftlichen Version übereinstimmt. §8 Abs. 1 lit. d PromO Ich versichere hiermit, dass zu einem vorherigen Zeitpunkt noch keine Promotion versucht wurde. In diesem Fall sind nähere Angaben über Zeitpunkt, Hochschule, Dissertationsthema und Ergebnis dieses Versuchs mitzuteilen. §9 Abs. 1 PromO Ich versichere hiermit, dass die vorliegende Dissertation selbstständig und nur unter Verwendung der angegebenen Quellen verfasst wurde. -

Universid Ade De Sã O Pa

A hardware/software codesign for the chemical reactivity of BRAMS Carlos Alberto Oliveira de Souza Junior Dissertação de Mestrado do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências de Computação e Matemática Computacional (PPG-CCMC) UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO DE SÃO UNIVERSIDADE Instituto de Ciências Matemáticas e de Computação Instituto Matemáticas de Ciências SERVIÇO DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO DO ICMC-USP Data de Depósito: Assinatura: ______________________ Carlos Alberto Oliveira de Souza Junior A hardware/software codesign for the chemical reactivity of BRAMS Master dissertation submitted to the Instituto de Ciências Matemáticas e de Computação – ICMC- USP, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of the Master Program in Computer Science and Computational Mathematics. FINAL VERSION Concentration Area: Computer Science and Computational Mathematics Advisor: Prof. Dr. Eduardo Marques USP – São Carlos August 2017 Ficha catalográfica elaborada pela Biblioteca Prof. Achille Bassi e Seção Técnica de Informática, ICMC/USP, com os dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a) Souza Junior, Carlos Alberto Oliveira de S684h A hardware/software codesign for the chemical reactivity of BRAMS / Carlos Alberto Oliveira de Souza Junior; orientador Eduardo Marques. -- São Carlos, 2017. 109 p. Dissertação (Mestrado - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências de Computação e Matemática Computacional) -- Instituto de Ciências Matemáticas e de Computação, Universidade de São Paulo, 2017. 1. Hardware. 2. FPGA. 3. OpenCL. 4. Codesign. 5. Heterogeneous-computing. I. Marques, Eduardo, orient. II. Título. Carlos Alberto Oliveira de Souza Junior Um coprojeto de hardware/software para a reatividade química do BRAMS Dissertação apresentada ao Instituto de Ciências Matemáticas e de Computação – ICMC-USP, como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências – Ciências de Computação e Matemática Computacional. -

Aldehydes and Ketones

12 Aldehydes and Ketones Ethanol from alcoholic beverages is first metabolized to acetaldehyde before being broken down further in the body. The reactivity of the carbonyl group of acetaldehyde allows it to bind to proteins in the body, the products of which lead to tissue damage and organ disease. Inset: A model of acetaldehyde. (Novastock/ Stock Connection/Glow Images) KEY QUESTIONS 12.1 What Are Aldehydes and Ketones? 12.8 What Is Keto–Enol Tautomerism? 12.2 How Are Aldehydes and Ketones Named? 12.9 How Are Aldehydes and Ketones Oxidized? 12.3 What Are the Physical Properties of Aldehydes 12.10 How Are Aldehydes and Ketones Reduced? and Ketones? 12.4 What Is the Most Common Reaction Theme of HOW TO Aldehydes and Ketones? 12.1 How to Predict the Product of a Grignard Reaction 12.5 What Are Grignard Reagents, and How Do They 12.2 How to Determine the Reactants Used to React with Aldehydes and Ketones? Synthesize a Hemiacetal or Acetal 12.6 What Are Hemiacetals and Acetals? 12.7 How Do Aldehydes and Ketones React with CHEMICAL CONNECTIONS Ammonia and Amines? 12A A Green Synthesis of Adipic Acid IN THIS AND several of the following chapters, we study the physical and chemical properties of compounds containing the carbonyl group, C O. Because this group is the functional group of aldehydes, ketones, and carboxylic acids and their derivatives, it is one of the most important functional groups in organic chemistry and in the chemistry of biological systems. The chemical properties of the carbonyl group are straightforward, and an understanding of its characteristic reaction themes leads very quickly to an understanding of a wide variety of organic reactions. -

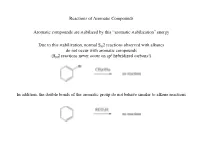

2 Reactions Observed with Alkanes Do Not Occur with Aromatic Compounds 2 (SN2 Reactions Never Occur on Sp Hybridized Carbons!)

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Aromatic compounds are stabilized by this “aromatic stabilization” energy Due to this stabilization, normal SN2 reactions observed with alkanes do not occur with aromatic compounds 2 (SN2 reactions never occur on sp hybridized carbons!) In addition, the double bonds of the aromatic group do not behave similar to alkene reactions Aromatic Substitution While aromatic compounds do not react through addition reactions seen earlier Br Br Br2 Br2 FeBr3 Br With an appropriate catalyst, benzene will react with bromine The product is a substitution, not an addition (the bromine has substituted for a hydrogen) The product is still aromatic Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Aromatic compounds react through a unique substitution type reaction Initially an electrophile reacts with the aromatic compound to generate an arenium ion (also called sigma complex) The arenium ion has lost aromatic stabilization (one of the carbons of the ring no longer has a conjugated p orbital) Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution In a second step, the arenium ion loses a proton to regenerate the aromatic stabilization The product is thus a substitution (the electrophile has substituted for a hydrogen) and is called an Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Energy Profile Transition states Transition states Intermediate Potential E energy H Starting material Products E Reaction Coordinate The rate-limiting step is therefore the formation of the arenium ion The properties of this arenium ion therefore control electrophilic aromatic substitutions (just like any reaction consider the stability of the intermediate formed in the rate limiting step) 1) The rate will be faster for anything that stabilizes the arenium ion 2) The regiochemistry will be controlled by the stability of the arenium ion The properties of the arenium ion will predict the outcome of electrophilic aromatic substitution chemistry Bromination To brominate an aromatic ring need to generate an electrophilic source of bromine In practice typically add a Lewis acid (e.g. -

Alkenes and Alkynes

02/21/2019 CHAPTER FOUR Alkenes and Alkynes H N O I Cl C O C O Cl F3C C Cl C Cl Efavirenz Haloprogin (antiviral, AIDS therapeutic) (antifungal, antiseptic) Chapter 4 Table of Content * Unsaturated Hydrocarbons * Introduction and hybridization * Alkenes and Alkynes * Benzene and Phenyl groups * Structure of Alkenes, cis‐trans Isomerism * Nomenclature of Alkenes and Alkynes * Configuration cis/trans, and cis/trans Isomerism * Configuration E/Z * Physical Properties of Hydrocarbons * Acid‐Base Reactions of Hydrocarbons * pka and Hybridizations 1 02/21/2019 Unsaturated Hydrocarbons • Unsaturated Hydrocarbon: A hydrocarbon that contains one or more carbon‐carbon double or triple bonds or benzene‐like rings. – Alkene: contains a carbon‐carbon double bond and has the general formula CnH2n. – Alkyne: contains a carbon‐carbon triple bond and has the general formula CnH2n‐2. Introduction Alkenes ● Hydrocarbons containing C=C ● Old name: olefins • Steroids • Hormones • Biochemical regulators 2 02/21/2019 • Alkynes – Hydrocarbons containing C≡C – Common name: acetylenes Unsaturated Hydrocarbons • Arene: benzene and its derivatives (Ch 9) 3 02/21/2019 Benzene and Phenyl Groups • We do not study benzene and its derivatives until Chapter 9. – However, we show structural formulas of compounds containing a phenyl group before that time. – The phenyl group is not reactive under any of the conditions we describe in chapters 5‐8. Structure of Alkenes • The two carbon atoms of a double bond and the four atoms bonded to them lie in a plane, with bond angles of approximately 120°. 4 02/21/2019 Structure of Alkenes • Figure 4.1 According to the orbital overlap model, a double bond consists of one bond formed by overlap of sp2 hybrid orbitals and one bond formed by overlap of parallel 2p orbitals. -

Organic Chemistry/Fourth Edition: E-Text

CHAPTER 17 ALDEHYDES AND KETONES: NUCLEOPHILIC ADDITION TO THE CARBONYL GROUP O X ldehydes and ketones contain an acyl group RC± bonded either to hydrogen or Ato another carbon. O O O X X X HCH RCH RCRЈ Formaldehyde Aldehyde Ketone Although the present chapter includes the usual collection of topics designed to acquaint us with a particular class of compounds, its central theme is a fundamental reaction type, nucleophilic addition to carbonyl groups. The principles of nucleophilic addition to alde- hydes and ketones developed here will be seen to have broad applicability in later chap- ters when transformations of various derivatives of carboxylic acids are discussed. 17.1 NOMENCLATURE O X The longest continuous chain that contains the ±CH group provides the base name for aldehydes. The -e ending of the corresponding alkane name is replaced by -al, and sub- stituents are specified in the usual way. It is not necessary to specify the location of O X the ±CH group in the name, since the chain must be numbered by starting with this group as C-1. The suffix -dial is added to the appropriate alkane name when the com- pound contains two aldehyde functions.* * The -e ending of an alkane name is dropped before a suffix beginning with a vowel (-al) and retained be- fore one beginning with a consonant (-dial). 654 Back Forward Main Menu TOC Study Guide TOC Student OLC MHHE Website 17.1 Nomenclature 655 CH3 O O O O CH3CCH2CH2CH CH2 CHCH2CH2CH2CH HCCHCH CH3 4,4-Dimethylpentanal 5-Hexenal 2-Phenylpropanedial When a formyl group (±CHœO) is attached to a ring, the ring name is followed by the suffix -carbaldehyde. -

Estimation of Hydrolysis Rate Constants of Carboxylic Acid Ester and Phosphate Ester Compounds in Aqueous Systems from Molecular Structure by SPARC

Estimation of Hydrolysis Rate Constants of Carboxylic Acid Ester and Phosphate Ester Compounds in Aqueous Systems from Molecular Structure by SPARC R E S E A R C H A N D D E V E L O P M E N T EPA/600/R-06/105 September 2006 Estimation of Hydrolysis Rate Constants of Carboxylic Acid Ester and Phosphate Ester Compounds in Aqueous Systems from Molecular Structure by SPARC By S. H. Hilal Ecosystems Research Division National Exposure Research Laboratory Athens, Georgia U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development Washington, DC 20460 NOTICE The information in this document has been funded by the United States Environmental Protection Agency. It has been subjected to the Agency's peer and administrative review, and has been approved for publication. Mention of trade names of commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. ii ABSTRACT SPARC (SPARC Performs Automated Reasoning in Chemistry) chemical reactivity models were extended to calculate hydrolysis rate constants for carboxylic acid ester and phosphate ester compounds in aqueous non- aqueous and systems strictly from molecular structure. The energy differences between the initial state and the transition state for a molecule of interest are factored into internal and external mechanistic perturbation components. The internal perturbations quantify the interactions of the appended perturber (P) with the reaction center (C). These internal perturbations are factored into SPARC’s mechanistic components of electrostatic and resonance effects. External perturbations quantify the solute-solvent interactions (solvation energy) and are factored into H-bonding, field stabilization and steric effects. These models have been tested using 1471 reliable measured base, acid and general base-catalyzed carboxylic acid ester hydrolysis rate constants in water and in mixed solvent systems at different temperatures. -

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Just Like an Alkene, Benzene Has Clouds of Electrons Above and Below Its Sigma Bond Framework

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Just like an alkene, benzene has clouds of electrons above and below its sigma bond framework. Although the electrons are in a stable aromatic system, they are still available for reaction with strong electrophiles. This generates a carbocation which is resonance stabilized (but not aromatic). This cation is called a sigma complex because the electrophile is joined to the benzene ring through a new sigma bond. The sigma complex (also called an arenium ion) is not aromatic since it contains an sp3 carbon (which disrupts the required loop of p orbitals). Ch17 Reactions of Aromatic Compounds (landscape).docx Page1 The loss of aromaticity required to form the sigma complex explains the highly endothermic nature of the first step. (That is why we require strong electrophiles for reaction). The sigma complex wishes to regain its aromaticity, and it may do so by either a reversal of the first step (i.e. regenerate the starting material) or by loss of the proton on the sp3 carbon (leading to a substitution product). When a reaction proceeds this way, it is electrophilic aromatic substitution. There are a wide variety of electrophiles that can be introduced into a benzene ring in this way, and so electrophilic aromatic substitution is a very important method for the synthesis of substituted aromatic compounds. Ch17 Reactions of Aromatic Compounds (landscape).docx Page2 Bromination of Benzene Bromination follows the same general mechanism for the electrophilic aromatic substitution (EAS). Bromine itself is not electrophilic enough to react with benzene. But the addition of a strong Lewis acid (electron pair acceptor), such as FeBr3, catalyses the reaction, and leads to the substitution product.