Human Rights Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The German Institute for Human Rights

Nova Acta Leopoldina NF 113, Nr. 387, 19 –24 (2011) The German Institute for Human Rights Beate Rudolf (Berlin) 1. Introduction The German Institute for Human Rights (Deutsches Institut für Menschenrechte) is the in- dependent National Human Rights Institution (NHRI) for Germany.1 It was established in March 2001 following a unanimous motion of the German federal parliament. In setting up a NHRI, Germany followed the example of many states, and heeded the recommendation made by the UN General Assembly in 1993.2 The German Institute for Human Rights is one of the few NHRIs that is organized as an institute, i.e. an institution with a focus on academic research. In its ten years of existence, the German Institute has acquired an excellent reputa- tion, both domestically and internationally. 2. National Human Rights Institutions The central purpose of National Human Rights Institutions is to help states comply with their obligations arising from international human rights law. NHRIs have been set up gradually in a number of countries since the early 1950s. The 1993 World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna brought new momentum to this development, emphasising the valuable contribution that NHRIs have made and can continue to make to promoting and protecting human rights on the national level. The UN General Assembly took up this idea; in its recommendation to the States, it incorporated the “Paris Principles”, a set of rules developed by academic experts that define NHRIs and the conditions for ensuring their independence.3 The Paris Principles provide that NHRIs must have a broad mandate to promote and pro- tect human rights. -

Human Rights and History a Challenge for Education

edited by Rainer Huhle HUMAN RIGHTS AND HISTORY A CHALLENGE FOR EDUCATION edited by Rainer Huhle H UMAN The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Genocide Convention of 1948 were promulgated as an unequivocal R response to the crimes committed under National Socialism. Human rights thus served as a universal response to concrete IGHTS historical experiences of injustice, which remains valid to the present day. As such, the Universal Declaration and the Genocide Convention serve as a key link between human rights education and historical learning. AND This volume elucidates the debates surrounding the historical development of human rights after 1945. The authors exam- H ine a number of specific human rights, including the prohibition of discrimination, freedom of opinion, the right to asylum ISTORY and the prohibition of slavery and forced labor, to consider how different historical experiences and legal traditions shaped their formulation. Through the examples of Latin America and the former Soviet Union, they explore the connections · A CHALLENGE FOR EDUCATION between human rights movements and human rights education. Finally, they address current challenges in human rights education to elucidate the role of historical experience in education. ISBN-13: 978-3-9810631-9-6 © Foundation “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future” Stiftung “Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft” Lindenstraße 20–25 10969 Berlin Germany Tel +49 (0) 30 25 92 97- 0 Fax +49 (0) 30 25 92 -11 [email protected] www.stiftung-evz.de Editor: Rainer Huhle Translation and Revision: Patricia Szobar Coordination: Christa Meyer Proofreading: Julia Brooks and Steffi Arendsee Typesetting and Design: dakato…design. David Sernau Printing: FATA Morgana Verlag ISBN-13: 978-3-9810631-9-6 Berlin, February 2010 Photo Credits: Cover page, left: Stèphane Hessel at the conference “Rights, that make us Human Beings” in Nuremberg, November 2008. -

Management Von Wachstum Und Globalisierung Best Practice

Werner G. Faix Stefanie Kisgen Jens Mergenthaler Ineke Blumenthal David Rygl Ardin Djalali (Hrsg.) Management von Wachstum und Globalisierung Best Practice Band 6 SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS S I AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP BE STEINBEIS UNIVERSITY BERLIN Werner G. Faix | Stefanie Kisgen | Jens Mergenthaler | Ineke Blumenthal David Rygl | Ardin Djalali (Hrsg.) Management von Wachstum und Globalisierung Band 6 WERNER G. FAIX | STEFANIE KISGEN | JENS MERGENTHALER | INEKE BLUMENTHAL | DAVID RYGL | ARDIN DJALALI (HRSG.) MANAGEMENT VON WACHSTUM UND GLOBALISIERUNG BAND 6 Impressum © 2018 Steinbeis-Edition Alle Rechte der Verbreitung, auch durch Film, Funk und Fernsehen, fotomechanische Wiederga- be, Tonträger jeder Art, auszugsweisen Nachdruck oder Einspeicherung und Rückgewinnung in Datenverarbeitungsanlagen aller Art, sind vorbehalten. Werner G. Faix, Stefanie Kisgen, Jens Mergenthaler, Ineke Blumenthal, David Rygl, Ardin Djalali (Hrsg.) Management von Wachstum und Globalisierung. Band 6 1. Auflage, 2018 | Steinbeis-Edition, Stuttgart ISBN 978-3-95663-179-5 Redaktion: SIBE GmbH (www.steinbeis-sibe.de) Satz und Umschlaggestaltung: Helene Sadilek, Lena Uphoff, Katsiaryna Kaliayeva Titelbild: Santos, Brazil, Sculpture by Tomie Ohtake at Marine Outfall / idegograndi / istockphoto.com | Printed in Germany 201218-2018-06 | www.steinbeis-edition.de VORWORT DER HERAUSGEBER Die SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP (SIBE) ist die in- ternationale Business School der Steinbeis-Hochschule Berlin (SHB). Die SIBE steht für erfolg- reichen -

German Perspectives on the Right to Life and Human Dignity in the “War on Terror” Saskia Hufnagel*

German Perspectives on the Right to Life and Human Dignity in the 'War on Terror' Author M. Hufnagel, Saskia Published 2008 Journal Title Criminal Law Journal Copyright Statement © 2008 Walter de Gruyter & Co. KG Publishers. The attached file is reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/40298 Link to published version http://www.thomsonreuters.com.au/catalogue/productdetails.asp?id=846 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au German perspectives on the right to life and human dignity in the “war on terror” Saskia Hufnagel* The purpose of this article is to examine, from a comparative perspective, how security concerns have limited three distinct human rights in Germany and Australia: the right to a fair trial, the right to life and the right to human dignity. Since human rights are rarely absolute, the “war on terror” has required legislatures and courts to determine the reasonable limits and qualifications to these rights. The German approach diverges from Australia in relation to the paramount constitutional status of the right to human dignity. Consequently, this German hierarchy of rights produces different outcomes in relation to the range and scope of permissible counter-terrorism measures. This is apparent in the ruling of the German Constitutional Court which declared void legislative powers authorizing the use of lethal force against hijacked aircraft. Similar powers inserted into the Defence Act 1903 (Cth) would not be amenable to similar challenge on grounds that they violate the right to human dignity. -

Violence Protection for Women in Germany

Englisch Gewaltprävention Mit Migranten für Migranten Violence protection for women in Germany revised edition A guide for women refugees, migrants and adolescents With support from: Impressum Gewaltschutz für Frauen in Deutschland – Ratgeber für geflüchtete Frauen, Migrantinnen und Jugendliche Herausgeber: Ethno-Medizinisches Zentrum e. V. Königstraße 6, 30175 Hannover Konzeption, Inhalt, Erstellung: Duale Hochschule Baden-Württemberg Villingen-Schwenningen (DHBW) – Institut für Transkulturelle Gesundheitsforschung Ethno-Medizinisches Zentrum e. V. (EMZ e. V.) – MiMi Integrationslabor Berlin (MiMi Lab) Förderung: Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Migration, Flüchtlinge und Integration Projektleitung: Ramazan Salman (EMZ e. V.), Prof. Dr. Dr. Jan Ilhan Kizilhan (DHBW) Redaktion: Jasmin Bergmann, Dagmar Freudenberg, Sarah Hoffmann, Olga Kedenburg, Ahmet Kimil, Prof. Dr. Dr. Jan Ilhan Kizilhan, Claudia Klett, Gabriele Martens, Ass. iur. Isabell Plich, Anne Rosenberg, Andreas Sauter, Ramazan Salman, Prof. Dr. Karin E. Sauer, Prof. Dr. Anja Teubert, Susanne Winkelmann, Lutz Winkelmann RA Layout und Satz: eindruck.net Übersetzung: Dolmetscherdienst – Ethno-Medizinisches Zentrum e. V. Bildquellen: Umschlagbild und Bild auf Seite 16 © Tom Platzer „Styling time4africa“ Ministerin Widmann-Mauz: Bundesregierung/Kugler · Seite 2: © iStock, imagesbybarbara Seite 5, 22, 25, 29: © Fotolia · Seite 11: © iStock, m-imagephotography Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwendung in anderen als den gesetzlich zugelassenen -

Land Use Planning and Control in the German Federal Republic

Volume 15 Issue 3 Summer 1975 Summer 1975 Land Use Planning and Control in the German Federal Republic Norman Wengert Recommended Citation Norman Wengert, Land Use Planning and Control in the German Federal Republic, 15 Nat. Resources J. 511 (1975). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nrj/vol15/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Resources Journal by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. LAND USE PLANNING AND CONTROL IN THE GERMAN FEDERAL REPUBLIC* NORMAN WENGERT** By American standards, land use planning and control in Germany is highly developed. In its effects it is considerably more comprehen- sive than land use planning in the United States, blanketing the entire country and dealing with a wide range of land use related subjects. Some would conclude, therefore, that it is more restrictive of both governmental and individual initiative and action. In any case, it seems obvious that the German experience would have considerable relevance to the American situation, if only because levels of indus- trialization are generally comparable, and both countries share a commitment to a market economic system and to democratic individualism. Although the literature on land use planning and control in the German Federal Republic' is substantial, very little has been written in English, and few German writings on the subject have been trans- lated. This article is, therefore, a beginning attempt to remedy this lack. -

Speakers / Panelists 9 December 2020 10:00 A.M. – 5:30 P.M. 70 Years of the European Convention on Human Rights Safeguarding H

Speakers / Panelists 9 December 2020 10:00 a.m. – 5:30 p.m. 70 Years of the European Convention on Human Rights Safeguarding Human Rights in Germany and Europe Heiko Maas Federal Foreign Minister Born in Saarlouis on 19 September 1966. Heiko Maas was appointed Federal Minister for Foreign Affairs on 14 March 2018. Before that, he served as Federal Minister of Justice and Consumer Protection in the previous government from 2013 until 2018. Before he was appointed Federal Minister in 2013, Heiko Maas had been a member of the Saarland State Government and a member of the Saarland Landtag (State Parliament) since 1994. In the Saarland, he served as Minister of Environment, Energy and Transport between 1998 and1999 and as Minister of Economics, Labour, Energy and Transport as well as Deputy Minister-President of Saarland from 2012 until 2013. He holds a law degree from the University of Saarland. Christine Lambrecht Federal Minister of Justice and Consumer Protection Christine Lambrecht has held the office of German Federal Minister of Justice and Consumer Protection since June 2019. She completed her law degree in 1995 and has been a Member of the German Bundestag since 1998. Among other positions, she has served as Member of the Bundestag’s Council of Elders and as Parliamentary State Secretary at the Federal Ministry of Finance. 1 Dr. Bärbel Kofler Federal Government Commissioner for Human Rights Policy and Humanitarian Assistance at the Federal Foreign Office Dr. Bärbel Kofler has been the Federal Government Commissioner for Human Rights Policy and Humanitarian Assistance since 2016. Her mandate includes advising the Federal Government on Germany’s human rights and humanitarian aid policies. -

Germany's Candidacy for a Seat on the UN Human Rights Council in 2013-2015

Germany’s candidacy for a seat on the UN Human Rights Council 2020 to 2022 Voluntary pledges and commitments pursuant to General Assembly Resolution 60/251 The Federal Republic of Germany has the pleasure to hereby present its candidacy to the Human Rights Council for the period from 2020 to 2022, with elections to be held in New York in October 2019. Having served on the Council in previous terms, most recently from 2015 to 2018, Germany has demonstrated its strong commitment to the Human Rights Council and its mechanisms, in particular by assuming the Presidency of the Council in 2015 and the Vice-Presidency in 2018. Germany strongly believes in cooperation between States in a rules-based, equitable multilateral order – in the field of human rights and beyond, supported by strong voices from civil society, including national human rights institutions. We seek a new term on the Human Rights Council to continue to promote human rights in all appropriate international and UN fora. Human rights are a cornerstone of Germany’s foreign policy and development cooperation. Human dignity and inviolable and inalienable human rights are enshrined in Article 1 of Germany’s Basic Law “as the basis of every community, of peace and of justice in the world”. The Basic Law thereby not only guarantees human rights in Germany, but also obliges the Federal Government to work to protect human dignity and fundamental freedoms throughout the world. We firmly believe in the universality of human rights as it is laid down by the United Nations in 1948 in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. -

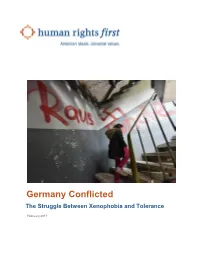

Germany Conflicted the Struggle Between Xenophobia and Tolerance

Germany Conflicted The Struggle Between Xenophobia and Tolerance February 2017 ON HUMAN RIGHTS, the United States must be a beacon. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Activists fighting for freedom around the globe continue to Research for this report was conducted by Susan Corke look to us for inspiration and count on us for support. and Erika Asgeirsson at Human Rights First and a team from Upholding human rights is not only a moral obligation; it’s a the University of Munich: Heather Painter, Britta vital national interest. America is strongest when our policies Schellenberg, and Klaus Wahl. Much of the research and actions match our values. consisted of interviews and consultations with human rights Human Rights First is an independent advocacy and action activists, government officials, national and international organization that challenges America to live up to its ideals. NGOs, multinational bodies, faith and interfaith groups, We believe American leadership is essential in the struggle scholars, and attorneys. We greatly appreciate their for human rights so we press the U.S. government and assistance and expertise. Rebecca Sheff, the former legal private companies to respect human rights and the rule of fellow with the antisemitism and extremism team, also law. When they don’t, we step in to demand reform, contributed to the research for this report during her time at accountability, and justice. Around the world, we work where Human Rights First. We are grateful for the team at Dechert we can best harness American influence to secure core LLP for their pro bono research on German law. At Human freedoms. Rights First, thanks to Sarah Graham for graphics and design; Meredith Kucherov and David Mizner for editorial We know that it is not enough to expose and protest injustice, assistance; Dora Illei for her research assistance; and so we create the political environment and policy solutions the communications team for their work on this report. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 3 June 2019

United Nations A/74/94 General Assembly Distr.: General 3 June 2019 Original: English Seventy-fourth session Item 116 (c) of the preliminary list* Elections to fill vacancies in subsidiary organs and other elections: election of members of the Human Rights Council Note verbale dated 30 May 2019 from the Permanent Mission of Germany to the United Nations addressed to the President of the General Assembly The Permanent Mission of the Federal Republic of Germany to the United Nations presents its compliments to the President of the General Assembly and has the honour to refer to the candidature of Germany for election to the Human Rights Council for the 2020–2022 term, at the elections to be held during the seventy-fourth session of the General Assembly. Therefore, in accordance with General Assembly resolution 60/251, the Government of Germany has the honour to submit herewith the voluntary pledges of Germany reaffirming its commitment to the promotion of and respect for all human rights and its active engagement in the work of the Human Rights Council (see annex). The Permanent Mission of the Federal Republic of Germany would be grateful if the present note and its annex could be circulated as a document of the General Assembly. * A/74/50. 19-09039 (E) 110619 *1909039* A/74/94 Annex to the note verbale dated 30 May 2019 from the Permanent Mission of Germany to the United Nations addressed to the President of the General Assembly Candidature of Germany to the Human Rights Council, 2020–2022 Voluntary pledges and commitments pursuant to General Assembly resolution 60/251 1. -

International Human Rights Instruments

70+6'& 0#6+105 *4+ +PVGTPCVKQPCN Distr. *WOCP4KIJVU GENERAL +PUVTWOGPVU HRI/CORE/1/Add.75/Rev.1 31 January 2003 Original: ENGLISH CORE DOCUMENT FORMING PART OF THE REPORTS OF STATES PARTIES GERMANY [15 November 2002] GE.03-40342 (E) 300403 HRI/CORE/1/Add.75/Rev.1 page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page I. COUNTRY AND POPULATION ............................................ 1 - 40 3 A. Geography and climate .................................................... 1 - 3 3 B. Demographic data ............................................................ 4 - 21 3 C. Economy .......................................................................... 22 - 40 6 II. GENERAL POLITICAL STRUCTURE ................................... 41 - 84 9 A. History ............................................................................. 41 - 52 9 B. The constitutional framework .......................................... 53 - 84 12 III. GENERAL STATUTORY FRAMEWORK WITHIN WHICH HUMAN RIGHTS ARE PROTECTED ..................... 85 - 132 20 A. Implementation of human rights in Germany .................. 85 - 125 20 B. International agreements .................................................. 126 - 132 28 IV. INFORMATION AND PUBLICATIONS ON HUMAN RIGHTS .............................................................. 133 - 138 31 HRI/CORE/1/Add.75/Rev.1 page 3 I. COUNTRY AND POPULATION A. Geography and climate 1. The Federal Republic of Germany has an area of 357,020 km2. It stretches from the North Sea and the Baltic Sea to the Alps in the south. Geographically it can be divided -

Preambel Constitution of the Free State of Bavaria

Preambel Constitution of the Free State of Bavaria 2nd December 1946 as last amended by the act of 10th November 2003 Mindful of the physical devastation which the survivors of the 2nd World War were led into by a godless state and social order lacking in all conscience or respect for human dignity, firmly intending moreover to secure permanently for future German generations the blessing of Peace, Humanity and Law, and looking back over a thousand years and more of history, the Bavarian people hereby bestows upon itself the following Democratic Constitution. 1. Chapter The foundations of the Bavarian State Article 1 Free state, Land colours, Land coat of arms (1) Bavaria is a free state. (2) The Land colours are white and blue. (3) The Land coat of arms shall be determined by law. Article 2 people's state (1) Bavaria is a people's state. The power of the state emanates from the people. (2) The people shall express their will through elections and votes. Decisions shall be arrived at by majority votes. Article 3 Law, Culture and social state (1) Bavaria is a legal, cultural and social state. It shall be dedicated to the common wellbeing. (2) The state shall protect the natural basis of life and cultural traditions. Article 3a Europe Bavaria declares itself part of a united Europe, which is committed to democratic, constitutional, social and federal principles as well as the principle of subsidiarity, which safeguards the independence of the regions and secures their involvement in European decisions. Bavaria shall work together with other European regions.