Comparative Floral Anatomy and Ontogeny in Magnoliaceae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

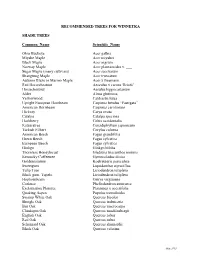

Recommended Trees for Winnetka

RECOMMENDED TREES FOR WINNETKA SHADE TREES Common_Name Scientific_Name Ohio Buckeye Acer galbra Miyabe Maple Acer miyabei Black Maple Acer nigrum Norway Maple Acer plantanoides v. ___ Sugar Maple (many cultivars) Acer saccharum Shangtung Maple Acer truncatum Autumn Blaze or Marmo Maple Acer x freemanii Red Horsechestnut Aesculus x carnea 'Briotii' Horsechestnut Aesulus hippocastanum Alder Alnus glutinosa Yellowwood Caldrastis lutea Upright European Hornbeam Carpinus betulus “Fastigata” American Hornbeam Carpinus carolinians Hickory Carya ovata Catalpa Catalpa speciosa Hackberry Celtis occidentalis Katsuratree Cercidiphyllum japonicum Turkish Filbert Corylus colurna American Beech Fagus grandifolia Green Beech Fagus sylvatica European Beech Fagus sylvatica Ginkgo Ginkgo biloba Thornless Honeylocust Gleditsia triacanthos inermis Kentucky Coffeetree Gymnocladus dioica Goldenraintree Koelreuteria paniculata Sweetgum Liquidambar styraciflua Tulip Tree Liriodendron tulipfera Black gum, Tupelo Liriodendron tulipfera Hophornbeam Ostrya virginiana Corktree Phellodendron amurense Exclamation Plantree Plantanus x aceerifolia Quaking Aspen Populus tremuloides Swamp White Oak Quercus bicolor Shingle Oak Quercus imbricaria Bur Oak Quercus macrocarpa Chinkapin Oak Quercus muehlenbergii English Oak Quercus robur Red Oak Quercus rubra Schumard Oak Quercus shumardii Black Oak Quercus velutina May 2015 SHADE TREES Common_Name Scientific_Name Sassafras Sassafras albidum American Linden Tilia Americana Littleleaf Linden (many cultivars) Tilia cordata Silver -

Beyond the Fringe

Beyond the Fringe By Margaret Klein Wilson, Fairfax Master Gardener Intern The final flourish of native spring flowering trees belongs to fringe trees (Chionanthus virginicus). The measured parade of seasonal color — dogwoods and redbuds, flowering cherry and plum — is neatly capped by the fluttering grace of abundant white blossoms that engulf this small, often edge habitat tree beginning in mid-May. Encountering a fringe tree on a breezy spring day is to see masses of white corollas of petals casting their light perfume across the landscape. Is it any wonder Linnaeus named Yale ©2021 Copyright and noted this genus Chionanthus (chion = University snow; anthos = flower) as he compiled the photo: Genera Plantarum (1753)? Less poetically, fringe tree’s common names include Old Man’s Beard, Grancy graybeard, flowering ash and white fringe tree. Genus Chionanthus is a member of the Olive Family, the Olaceae, which includes 29 genera and over 600 species of trees and shrubs common in southeastern Asia and Australasia. Trees in this genus have uses both practical and ornamental: olive for food, ash for its lumber, and forsythia, gardenia and privets for sheer domestic beauty. In North America, ash trees in the genus Fraxinus, devilwood (Osmantus americanus) and Forestiera (swampprivet) are fringe tree’s near relatives. Only two species of fringe tree exist: C. virginicus in eastern North America and C. retusus, native to China. In his citation naming fringe tree the Virginia Native Plant Society 1997 Wildflower of the Year, C. F. Saachi explains this geographic disconnect: “This unusual biogeographic pattern, with different species within a genus … separated by several thousand miles, is a product of major geologic events including mountain building and the effects of glaciation. -

Indiana's Native Magnolias

FNR-238 Purdue University Forestry and Natural Resources Know your Trees Series Indiana’s Native Magnolias Sally S. Weeks, Dendrologist Department of Forestry and Natural Resources Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 This publication is available in color at http://www.ces.purdue.edu/extmedia/fnr.htm Introduction When most Midwesterners think of a magnolia, images of the grand, evergreen southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) (Figure 1) usually come to mind. Even those familiar with magnolias tend to think of them as occurring only in the South, where a more moderate climate prevails. Seven species do indeed thrive, especially in the southern Appalachian Mountains. But how many Hoosiers know that there are two native species Figure 2. Cucumber magnolia when planted will grow well throughout Indiana. In Charles Deam’s Trees of Indiana, the author reports “it doubtless occurred in all or nearly all of the counties in southern Indiana south of a line drawn from Franklin to Knox counties.” It was mainly found as a scattered, woodland tree and considered very local. Today, it is known to occur in only three small native populations and is listed as State Endangered Figure 1. Southern magnolia by the Division of Nature Preserves within Indiana’s Department of Natural Resources. found in Indiana? Very few, I suspect. No native As the common name suggests, the immature magnolias occur further west than eastern Texas, fruits are green and resemble a cucumber so we “easterners” are uniquely blessed with the (Figure 3). Pioneers added the seeds to whisky presence of these beautiful flowering trees. to make bitters, a supposed remedy for many Indiana’s most “abundant” species, cucumber ailments. -

THE Magnoliaceae Liriodendron L. Magnolia L

THE Magnoliaceae Liriodendron L. Magnolia L. VEGETATIVE KEY TO SPECIES IN CULTIVATION Jan De Langhe (1 October 2014 - 28 May 2015) Vegetative identification key. Introduction: This key is based on vegetative characteristics, and therefore also of use when flowers and fruits are absent. - Use a 10× hand lens to evaluate stipular scars, buds and pubescence in general. - Look at the entire plant. Young specimens, shade, and strong shoots give an atypical view. - Beware of hybridisation, especially with plants raised from seed other than wild origin. Taxa treated in this key: see page 10. Questionable/frequently misapplied names: see page 10. Names referred to synonymy: see page 11. References: - JDL herbarium - living specimens, in various arboreta, botanic gardens and collections - literature: De Meyere, D. - (2001) - Enkele notities omtrent Liriodendron tulipifera, L. chinense en hun hybriden in BDB, p.23-40. Hunt, D. - (1998) - Magnolias and their allies, 304p. Bean, W.J. - (1981) - Magnolia in Trees and Shrubs hardy in the British Isles VOL.2, p.641-675. - or online edition Clarke, D.L. - (1988) - Magnolia in Trees and Shrubs hardy in the British Isles supplement, p.318-332. Grimshaw, J. & Bayton, R. - (2009) - Magnolia in New Trees, p.473-506. RHS - (2014) - Magnolia in The Hillier Manual of Trees & Shrubs, p.206-215. Liu, Y.-H., Zeng, Q.-W., Zhou, R.-Z. & Xing, F.-W. - (2004) - Magnolias of China, 391p. Krüssmann, G. - (1977) - Magnolia in Handbuch der Laubgehölze, VOL.3, p.275-288. Meyer, F.G. - (1977) - Magnoliaceae in Flora of North America, VOL.3: online edition Rehder, A. - (1940) - Magnoliaceae in Manual of cultivated trees and shrubs hardy in North America, p.246-253. -

A Note on Magnolia, Mainly of Sections Manglietia and Michelia Subgenus

A note on Magnolia, mainly of sections Manglietia and Michelia subgenus Magnolia (Magnoliaceae) A note of caution concerning the ultimate heights that may be achieved in cultivation by numerous of the newer evergreen magnolias from Asia, is the theme of this article by CHRIS CALLAGHAN and S. K. PNG of the Australian Bicentennial Arboretum (ABA). Following Thomas Methuen-Campbell’s interesting report in the 2011 IDS Yearbook concerning the study weekend held in June of that year at RHS Wisley, Surrey, to discuss “summer” flowering magnolias (see Endnote), the authors thought they should write to mention an important consideration before contemplating planting of these trees in gardens, or indeed any tree in a garden, particularly the average small garden. We are not sure if the ultimate size of many of these magnolias was discussed with those attending the study weekend, since most of their maximum known heights were not mentioned in the article. However, we believe any readers tempted by the article to purchase and plant out most of the evergreen magnolias featured (previously in the genera Manglietia, Michelia or Parakmeria) in a normal suburban front or backyard in relatively 46 warm, sheltered, near frost-free areas, will be ultimately dismayed by the sizes they reach (see Figlar 2009 for reasons behind the reduction of genera). Even allowing that these predominantly warm-temperate to sub-tropical forest trees may not achieve their maximum potential sizes in the milder regions of temperate Europe, most are still likely to overtop (and overshadow!) two or three storey homes or apartments, especially with a warming climate. -

The Red List of Magnoliaceae Revised and Extended

The Red List of Magnoliaceae revised and extended Malin Rivers, Emily Beech, Lydia Murphy & Sara Oldfield BOTANIC GARDENS CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL (BGCI) is a membership organization linking botanic gardens in over 100 countries in a shared commitment to biodiversity conservation, sustainable use and environmental education. BGCI aims to mobilize botanic gardens and work with partners to secure plant diversity for the Published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, well-being of people and the planet. BGCI provides the Secretariat for Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3BW, UK. the IUCN/SSC Global Tree Specialist Group. © 2016 Botanic Gardens Conservation International ISBN-10: 1-905164-64-5 ISBN-13: 978-1-905164-64-6 Reproduction of any part of the publication for educational, conservation and other non-profit FAUNA & FLORA INTERNATIONAL (FFI) , founded in 1903 and the purposes is authorized without prior permission from world’s oldest international conservation organization, acts to conserve the copyright holder, provided that the source is fully acknowledged. threatened species and ecosystems worldwide, choosing solutions that are sustainable, are based on sound science and take account of Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes human needs. is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. Recommended citation: Rivers, M., Beech, E., Murphy, L. and Oldfield, S. (2016). The Red List of Magnoliaceae - revised and extended. BGCI. Richmond, UK. AUTHORS Malin Rivers is the Red List Manager at BGCI. THE GLOBAL TREES CAMPAIGN (GTC) is undertaken through a Emily Beech is a Conservation Assistant at BGCI. partnership between BGCI and FFI. GTC’s mission is to prevent all tree Lydia Murphy is the Global Trees Campaign Intern species extinctions in the wild, ensuring their benefits for people, wildlife at BGCI. -

Phylogenomic Approach

Toward the ultimate phylogeny of Magnoliaceae: phylogenomic approach Sangtae Kim*1, Suhyeon Park1, and Jongsun Park2 1 Sungshin University, Korea 2 InfoBoss Co., Korea Mr. Carl Ferris Miller Founder of Chollipo Arboretum in Korea Chollipo Arboretum Famous for its magnolia collection 2020. Annual Meeting of Magnolia Society International Cholliop Arboretum in Korea. April 13th~22th, 2020 http://WWW.Chollipo.org Sungshin University, Seoul, Korea Dr. Hans Nooteboom Dr. Liu Yu-Hu Twenty-one years ago... in 1998 The 1st International Symposium on the Family Magnoliaceae, Gwangzhow Dr. Hiroshi Azuma Mr. Richard Figlar Dr. Hans Nooteboom Dr. Qing-wen Zeng Dr. Weibang Sun Handsome young boy Dr. Yong-kang Sima Dr. Yu-wu Law Presented ITS study on Magnoliaceae - never published Ten years ago... in 2009 Presented nine cp genome region study (9.2 kbp) on Magnoliaceae – published in 2013 2015 1st International Sympodium on Neotropical Magnoliaceae Gadalajara, 2019 3rd International Sympodium and Workshop on Neotropical Magnoliaceae Asterales Dipsacales Apiales Why magnolia study is Aquifoliales Campanulids (Euasterids II) Garryales Gentianales Laminales Solanales Lamiids important in botany? Ericales Asterids (Euasterids I) Cornales Sapindales Malvales Brassicales Malvids Fagales (Eurosids II) • As a member of early-diverging Cucurbitales Rosales Fabales Zygophyllales Celestrales Fabids (Eurosid I) angiosperms, reconstruction of the Oxalidales Malpighiales Vitales Geraniales Myrtales Rosids phylogeny of Magnoliaceae will Saxifragales Caryphyllales -

Phylogeny of Angiosperms Angiosperm “Basal Angiosperm”

Phylogeny of angiosperms Angiosperm “Basal angiosperm” AmborellaNymphaealesAustrobaileyalesMagnoliidss Monocots Eudicots Parallel venation scattered vascular bundles 1 cotyledon Tricolpate pollen Magnoliids is a monophyletic group including Magnoliaceae, Lauraceae, Piperaceae and several other families After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374 Magnoliaceae (Magnolia family) Textbook DVD KRR Magnolia X soulangeana; Magnoliaceae (Magnolia family) Textbook DVD WSJ Textbook DVD KRR Magnolia grandiflora; Magnolia macrophylla; Note leaf simple, entire, pinnate venation, numerous tepals, numerous stamens and carples. Textbook DVD KRR Magnolia sieboldii; Magnoliaceae (Magnolia family) Textbook DVD KMN Textbook DVD SMK-KRR Magnolia figo; Magnolia grandiflora; Note the elongated receptacle, Note the aggregate of follicles, and laminar stamens and red fleshy seed coat Magnoliaceae (Magnolia family) Photo: Yaowu Yuan Photo: Yaowu Yuan Liriodendron tulipifera; Note the elongated receptacle, and laminar stamens Magnoliaceae (Magnolia family) Note the lobed, T-shirt-like leaf, and pinnate venation Note the aggregate of samara Magnoliaceae (Magnolia family) Magnoliaceae - 2 genera/220 species. Trees or shrubs; Ethereal oils (aromatic terpenoids) - (remember the smell of bay leaves?); Leaves alternate, simple (Magnolia) or lobed (Liriodendron), entire; Flowers large and showy, actinomorphic, bisexual Tepals 6-numerous, stamens and carpels numerous, Spirally arranged on an elongated receptacle, Laminar stamens poorly differentiated into anther and filament. Fruit usually an aggregate of follicle (Magnolia) or samara (Liriodendron); follicle: 1-carpellate fruit that dehisces on the side samara: 1-carpellate winged, indehiscent fruit Phylogeny of Eudicots (or Tricolpates) Eudicots (or Tricolpates) “Basal eudicots” Asterids Buxales Rosids Caryophyllales RanunculalesProteales Ranunculales is a monophyletic group including Ranunculaceae, Berberidaceae, Papaveraceae, and 4 other families. After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. -

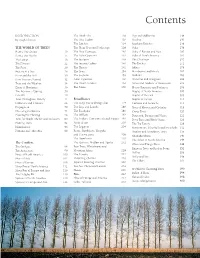

Trees K2 3/2/10 14:10 Page 1

Trees K Blad PGc 2.02.10:Trees K2 3/2/10 14:10 Page 1 Contents INTRODUCTION The Hemlocks 128 Figs and Mulberries 248 by Hugh Johnson The True Cedars 130 Beeches 250 The Larches 134 Southern Beeches 256 THE WORLD OF TREES The Plum Yews and Podocarps 138 Oaks 258 How a Tree Grows 10 The True Cypresses 140 Oaks of Europe and Asia 260 How a Tree Works 14 The False Cypresses 142 Oaks of North America 264 The Leaves 18 The Junipers 146 The Chestnuts 270 The Flowers 22 The Incense Cedars 150 The Birches 272 The Fruit 26 The Thujas 152 Alders 278 History in a Tree 28 The Yews 154 Hornbeams and Hazels 282 Roots and the Soil 30 The Sequoias 156 Walnuts 286 How Trees are Named 32 Asian Cypresses 160 Hickories and Wingnuts 288 Trees and the Weather 34 The Dwarf Conifers 162 Limes and Lindens or Basswoods 292 Zones of Hardiness 36 The Palms 166 Horse Chestnuts and Buckeyes 296 The Advance of Spring 38 Maples of North America 300 Forestry 40 Maples of the East 306 Trees Throughout History 44 Broadleaves Maples of Europe 310 Collectors and Creators 64 The Tulip Tree and Magnolias 174 Cashews and Sumachs 316 Propagation 70 The Bays and Laurels 180 Trees of Heaven and Cedrelas 318 Choosing the Species 72 The Eucalypts 186 Citrus Trees 320 Planning for Planting 76 The Willows 192 Dogwood, Davidia and Nyssa 322 Trees for Shade, Shelter and Seclusion 80 The Poplars, Cottonwoods and Aspens 196 Dove Trees and Black Gums 326 Planting Trees 82 Antipodeans 200 The Tea Family 328 Maintenance 86 The Legumes 204 Persimmons, Silverbells and Snowbells 332 Pruning and -

Effective Heat Transport During Miocene Cooling

EGU Journal Logos (RGB) Open Access Open Access Open Access Advances in Annales Nonlinear Processes Geosciences Geophysicae in Geophysics Open Access Open Access Natural Hazards Natural Hazards and Earth System and Earth System Sciences Sciences Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric Chemistry Chemistry and Physics and Physics Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric Measurement Measurement Techniques Techniques Discussions Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Open Access Biogeosciences Discuss., 10, 13563–13601, 2013 Open Access www.biogeosciences-discuss.net/10/13563/2013/ Biogeosciences Biogeosciences BGD doi:10.5194/bgd-10-13563-2013 Discussions © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 10, 13563–13601, 2013 Open Access Open Access This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal BiogeosciencesClimate (BG). Climate Effective heat Please refer to the correspondingof finalthe Past paper in BG if available. of the Past Discussions transport during Miocene cooling Open Access Open Access Earth System Earth System T. Denk et al. Effective heat transportDynamics of Gulf StreamDynamics to Discussions subarctic North Atlantic during Miocene Title Page Open Access Geoscientific Geoscientific Open Access cooling: evidenceInstrumentation from “KöppenInstrumentation Abstract Introduction Methods and Methods and signatures” ofData fossil Systems plant assemblagesData Systems Conclusions References Discussions Open Access Open Access Tables Figures 1 1 2 2 Geoscientific T. Denk , G. W. Grimm , F.Geoscientific Grímsson , and R. Zetter Model Development 1 Model Development J I Swedish Museum of Natural History, Department of Palaeobotany, Box 50007,Discussions 10405 Stockholm, Sweden 2 J I Open Access University of Vienna, Department of Palaeontology,Open Access Althanstrasse 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria Hydrology and Hydrology and Back Close Received: 8 July 2013 – Accepted:Earth System 31 July 2013 – Published: 15 AugustEarth 2013 System Correspondence to: T. -

Magnolia Obovata

ISSUE 80 INAGNOLN INagnolla obovata Eric Hsu, Putnam Fellow, Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University Photographs by Philippe de 8 poelberch I first encountered Magnolia obovata in Bower at Sir Harold Hillier Gardens and Arboretum, Hampshire, England, where the tightly pursed, waxy, globular buds teased, but rewarded my patience. As each bud unfurled successively, it emitted an intoxicating ambrosial bouquet of melons, bananas, and grapes. Although the leaves were nowhere as luxuriously lustrous as M. grandrflora, they formed an el- egant wreath for the creamy white flower. I gingerly plucked one flower for doser observation, and placed one in my room. When I re- tumed from work later in the afternoon, the mom was overpowering- ly redolent of the magnolia's scent. The same olfactory pleasure was later experienced vicariously through the large Magnolia x wiesneri in the private garden of Nicholas Nickou in southern Connecticut. Several years earlier, I had traveled to Hokkaido Japan, after my high school graduation. Although Hokkaido experiences more severe win- ters than those in the southern parts of Japan, the forests there yield a remarkable diversity of fora, some of which are popular ornamen- tals. When one drives through the region, the silvery to blue-green leaf undersides of Magnolia obovata, shimmering in the breeze, seem to flag the eyes. In "Forest Flora of Japan" (sggII), Charles Sargent commended this species, which he encountered growing tluough the mountainous forests of Hokkaido. He called it "one of the largest and most beautiful of the deciduous-leaved species in size and [the seed conesj are sometimes eight inches long, and brilliant scarlet in color, stand out on branches, it is the most striking feature of the forests. -

The Progressive and Ancestral Traits of the Secondary Xylem Within Magnolia Clad – the Early Diverging Lineage of Flowering Plants

Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER Acta Soc Bot Pol 84(1):87–96 DOI: 10.5586/asbp.2014.028 Received: 2014-07-31 Accepted: 2014-12-01 Published electronically: 2015-01-07 The progressive and ancestral traits of the secondary xylem within Magnolia clad – the early diverging lineage of flowering plants Magdalena Marta Wróblewska* Department of Developmental Plant Biology, Institute of Experimental Biology, University of Wrocław, Kanonia 6/8, 50-328 Wrocław, Poland Abstract The qualitative and quantitative studies, presented in this article, on wood anatomy of various species belonging to ancient Magnolia genus reveal new aspects of phylogenetic relationships between the species and show evolutionary trends, known to increase fitness of conductive tissues in angiosperms. They also provide new examples of phenotypic plasticity in plants. The type of perforation plate in vessel members is one of the most relevant features for taxonomic studies. InMagnolia , until now, two types of perforation plates have been reported: the conservative, scalariform and the specialized, simple one. In this paper, are presented some findings, new to magnolia wood science, like exclusively simple perforation plates in some species or mixed perforation plates – simple and scalariform in one vessel member. Intravascular pitting is another taxonomically important trait of vascular tissue. Interesting transient states between different patterns of pitting in one cell only have been found. This proves great flexibility of mechanisms, which elaborate cell wall structure in maturing trache- ary element. The comparison of this data with phylogenetic trees, based on the fossil records and plastid gene expression, clearly shows that there is a link between the type of perforation plate and the degree of evolutionary specialization within Magnolia genus.